The Old, Havana Way

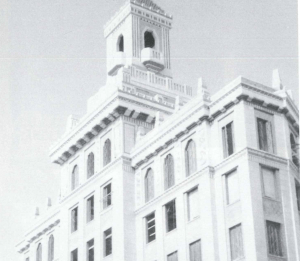

The Bacardi building in Old Havana. Photo by Lorena Barbara.

Memory is redundant: it repeats signs

so that the city can begin to exist.

Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

Havana, the gracious Antillean metropolis opening into the straits of Florida, has grown at a very slow pace compared to most other major Latin American cities. Its historical heritage, found in the nooks and crannies of old tenements and office buildings, benefited from the benign neglect of the 1959 revolution, which concentrated its efforts on the more undeveloped countryside. Although these policies increased deterioration and overcrowding in the capital city, demolitions driven by real estate speculation did not do away with its multi-faceted layers of architectural history, as in other major Latin American cities. Tourists are now drawn to the historical buildings and the anachronistic nature of the city, as they wander and remark on the old cars lining the streets and the architectural gems found on every street corner, ranging from examples of colonial to Art Deco to modernism.

As Cuba began to think more about tourism as a source of foreign revenue in the 1990s, new dollar-oriented programs resulted in hotels and condos for foreigners. The majority of those buildings followed bland, banal designs meant to please customers seeking a “tropical” architecture, but a few good ones started to appear at the turn of millennia. This still early trend addresses the goal of bringing back architecture into the realm of culture, an issue that received unanimous support during the seminal 6th Congress of the Cuban National Union of Writers and Artists (UNEAC) in November 1998, which debated the issue for an entire morning session.

The challenge now is to balance city, tourism, and preservation. The city’s built stock includes a very large, valuable architectural heritage. The colonial period, from 1519 to 1898, includes the first fort (La Fuerza, 1577) and aqueduct (Zanja Real, 1592) made by Europeans in America; pre-Baroque buildings from the 1600s with a strong mudéjar (Spanish Moorish) influence are best represented by the huge Santa Clara nunnery; a sober Baroque period, from the second half of the 1700s and early 1800s, has the façade of Havana’s cathedral as its landmark; some neogothic and great neoclassical villas were mostly built beyond the old walled precinct around the mid-1800s. The original 354 acre-core known as Old Havana, a peninsula protruding into the well-protected bay, was designated World Heritage by UNESCO in 1982, together with the 19th century expansion in the ring formerly occupied by the walls, and the most impressive colonial defensive system in America, including the largest fortress, La Cabaña (1774), Atarés (1767), and El Príncipe (1779), all built after Spain recovered Havana from the English in 1763.

This substantial colonial heritage is almost overwhelmed, however, by a relevant stock of 20th century buildings that include a short period of Art Nouveau, with a strong influence of Catalan Modernisme, in the first decade, followed by an ubiquitous eclectic architecture from 1910 to the early 1930s that included everything from upper-class mansions and great public buildings like the Presidential Palace or the Capitol, to lower/middle and even working-class dwellings. In fact, eclectic architecture accounts for the largest part of the built stock in the central districts of Havana and in most other Cuban cities. There is also a large stock of Art Deco, embodied by the outstanding Bacardí building (1930), Havana’s equivalent to the Chrysler building, followed by a short modern monumental period in the early 1940s, limited to public buildings.

The second relevant construction boom in Havana, comparable to the fat cows period fueled by the sudden rise in the price of sugar because of the first World War, came after the second World War, with a quick spread of architecture from the Modern movement. It was also the time when large suburban expansion occurred, with dozens of new subdivisions or repartos. Modern architecture continued its dominance into the 1960s after the revolution came to power, with some relevant building compounds like the schools of arts, CUJAE and Habana del Este. Put together, this relevant heritage covers more than 5,000 acres under landmark protection. Prefabrication and mass-produced social housing took command afterwards, leaving little room for good design, except in some special works placed mostly at the periphery and therefore contributing little to the city’s image.

For a short period during the 1980s, young architects experimented with postmodernism, which was already fading away abroad. Cuban art historian Graziella Pogolotti observed that Cuba is a port, and this shows in the blend of foreign influences, well-digested or not, that have stamped themselves on Cuban culture over time, leaving only a faint trace of the native inhabitants. These influences were Spanish (including Spanish-Moorish), French, and finally American. Immigrants from West Africa and southern China, brought as slaves or semi-slaves, left a strong imprint on Cuban culture, but did not directly influence its built environment. Forty years of strong economic and political ties to the Soviet Union and Eastern European socialist bloc left behind a surprisingly weak influence on the built environment, mainly found in the heavy-panel prefabricated technology for housing tracts, and the now aging Russian-made cars that compete with the American vintage ones from the 1950s.

ECONOMY AND TOURISM AT THE BEGINNING OF THE 21ST CENTURY

As with many other countries in the global South, tourism represents for Cuba the main source of hard currency coming from the North. Tourism increased from 2,000 tourists in 1967 to 1.4 million in 1998. Havana is a major destination: 55.1% of all tourists visit the city and contribute 26% of all the national dollar revenue from tourism. Tourist spend more than twice as much money in Havana than the national average (GDIC 2000). The capital city has a strong cultural and social appeal to visitors, but it also offers more than five miles of fine beaches only 20 minutes east from the center. Havana’s total capacity was 10,700 rooms (of the 31,600 nationwide) in early 2000. Approximately 4,500 more rooms are located in private residences renting to foreigners; this figure is the equivalent of 12 to 15 new hotels, but it only accounts for those rooms registered and paying taxes, so the actual figure is likely to be at least twice that. In 2000, tourism grew nationally only 9-10%, less than the average 18.6% of the last five years, because of the devaluation of the Euro against the dollar and the rise in the price of airfare. Nonetheless, there were five times as many tourists than in 1989, and 61% of the products consumed were made in Cuba, but the cost increased in four cents for each dollar earned, according to a December 2000 presentation to the Cuban National Assembly.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, Cuba has made city tourism its first priority, while beach and sun are second. Other sorts of tourism like rural expeditions, horse-riding, bird-watching, scuba-diving, bicycling, or path-walking are still not adequately promoted, taking little advantage of amazing natural resources. The rise of Cuba as an attractive tourist destination has worried other Caribbean countries. Rather than competing, however, coordination may prove to be helpful since the proximity of these island countries permits multiple-destinations for tourists from far away, which would ultimately be more profitable to all the islands.

Immediately after the terrorist attacks on September 11 last year, the flow of tourists to Cuba dropped, as happened all around the world. In a press conference on October 20, 2001 (Mayoral 2001) the Minister of Tourism, Ibrahim Ferradaz, addressed the extended concerns about the fate of tourism, now standing with sugar as the main source of badly-needed hard currency income. The number of night stays decreased by 5% compared to September 2000, while a 10% growth had been formerly expected. But by October 1st, 2001 there were 2,100 more tourists than on the same date in 2000. Tourism from Canada, which leads the Cuban market in 2001, grew during September and is expected to improve during the “high” season in winter. Cuba is considered a very safe destination for tourists, something especially attractive at the moment, and foreign partners with their own market networks manage 50% of the total amount of rooms. Nevertheless, the 2 million-tourist goal for 2001 will not be achieved, and the expected growth of 12.7% will fall to 5-7%. The most affected destinations are presently Havana and Varadero, while Pinar del Río, Trinidad, and the Jardines del Rey keys have slightly improved. To cut costs, the Ministry closed 20 hotels including Capri and Trópico in Havana, using this opportunity to repair some of them. Other hotels like Habana Libre, Cohiba, and Riviera in Havana fully closed their doors, and tourists have been allocated to fewer hotels. Tourism is a very vulnerable industry, and its future depends to a large extent on whether terrorist attacks continue or not, and on the evolution of the war in the Middle East against a faceless, ubiquitous enemy who, like Poe’s Red Death, is already inside.

TOURISM AND ENVIRONMENT

Tourism has often been compared to a locomotive hauling economic development, but it may also turn into a destruction machine of the natural, the built, and the social environment. A 1997 environmental law and a 2000 Coastal Zones Management law, which require new investments to obtain an environmental license, reflect concern about environmental protection. Ecological balance is especially vulnerable in small island countries, and even if Cuba is by far the largest island in the Caribbean, it is composed of many well-defined but small ecosystems that can be easily ruined in an irreversible way. One of the major poles for sun and sand tourism now being developed, Jardines del Rey, which covers a strip more than 200 miles long with 2,517 islands along the northern coast of central Cuba.

The quick flow of investments into the many wild beaches and keys of the Cuban archipelago has started to affect biodiversity. This calls for a long-term approach to development, one that will not kill the source of profits itself. Inappropriate technologies and building materials and excessive alterations on the terrain are associated with construction projects that are visually jarring with the surroundings. Banal architectural designs, often imported from abroad by the foreign investor or blandly copied by Cuban designers, usually lack a national and local identity and do not take advantage of the climate. Negative impacts on the environment affect the habitat for the local fauna and vegetation, alter the natural topography, introduce exotic plants, change the shape and character of the local landscape, or destroy wetlands and sand dunes through building in the frail strip where sea and land interact.

Quarries and excessive deforestation to clear land for hotel sites and their surrounding installations disturb ecological balance, as does the construction of airports and roads which connect the main island with the keys (pedraplenes), often blocking the natural recirculation of seawater. Inappropriate wastewater treatment or the filling of lagoons adds to the ecological threats. Sustainable approaches, such as low-consumption designs that preserve energy and water and use natural ventilation and lighting, are only experimentally used. Ironically, this narrow-minded approach of looking for fast profits is endangering the very thing that attracts visitors (i.e. the source of profits): the pristine environment.

INMOBILARIAS

Around 80% of recent construction activity in Cuba is linked to tourism and real estate projects known as inmobiliarias, condos for foreigners. Joint ventures are mainly with Spanish, Canadian, Italian, and Israeli associates. The Cuban contribution represents an estimated $500 million, according to a March 2000 Lincoln Institute of Land Policy study, “Using Land Value to Promote Development in Cuba.”

Land has been the main Cuban contribution, and to a lesser extent the supply of construction workers and some basic building materials. New projects have often been criticized for excessive use of land, with too high densities and little open space. Investors try to justify this claiming the high price they must pay for the land is the culprit. Land leasing on a 25-year term (that can be extended to another 25 if both partners agree) has always been preferred instead of selling. A law regulating land usage has been discussed for many years, but still has not been approved.

In May 2000 the Cuban government decided to forbid sales of apartments to foreigners, allowing only deals in progress to proceed, but foreigners in the future will only be able to rent. Preserving national property by not selling to foreigners may seem a correct decision, but this approach tends to look at real estate businesses as one-time sources of income, without capturing land value increments. On the other hand, the decision about land value is made without using price as a planning tool to encourage or discourage construction on certain locations, with no systematic updating of prices. This leads to the exploitation of short-run profits, with buildings as big as possible, actually bigger than they should be, fitting badly in large vacant lots within the existing urban fabric, usually made up of much smaller lots and narrow, low-rise buildings set close to each other. Residents don’t see any direct benefit from the newcomers, which instead overload their already critical utilities.

For instance, Monte Barreto is a developing zone on a large tract of land in western Havana with more than 100 acres that remained barren up until the mid 1970s. It has a privileged location, overlooking the sea and crossed by the beautiful Fifth Avenue, the heart of the former upscale Miramar district. The development pattern of this area proved to be shortsighted: buildings were placed parallel to the shore, starting with those that were built first. As a result, four hotels (Tritón, Neptuno, Mel¡-Habana and Panorama, the latter under construction) completely fill that front line, leaving pedestrians and the rest of the new buildings without access or even ground-level views to the sea. Behind that first row will be two more strips, occupied by the eighteen buildings of the Miramar Trade Center with 1.9 million square feet for offices and shops, plus 750,000 square feet for parking for 2,000 cars. By mid-2001 only two of these buildings had been finished, but four more are scheduled for construction. Three additional hotels are slated for a location further away from the sea and south of Fifth Avenue. One, the Miramar-Novotel, has been built, and another is presently under construction. Even farther south remains an open space with some natural caves and unique vegetation to be preserved as a public park.

However, a much wiser general layout would leave a linear central park running all the way north to south into the sea, lined with buildings that could all have two great views, a direct one onto the park and another slanted onto the ocean. This public space might perform as a social leveler, bringing together foreigners and Cubans—or, in the future, just different kinds of people with different income levels. The whole complex of more than 100 acres is dollar-oriented, with no room for a badly needed mixed-development that would include other urban functions and different levels of income and social strata. This district gives a hint of what might become a car-oriented consumerist pattern of suburban development that will unfortunately reshape the image of Havana and change the traditional way people behave in public spaces. A lesson can be learned from the Monte Barreto experience: diversity does more than just preserve nature.

PRESERVATION PAYS

Symbolically, the first two laws passed by the then-new National Assembly in December 1976 were dedicated to historic preservation: Law # 1, on National Cultural Heritage, and Law # 2 on National and Local Landmarks. Preservation since the early 1960s had been mostly focused on the restoration of some very relevant buildings, but projects increased and the scope expanded after the early 1980s when the City Historian´s office took over as the main investor for restoration in Old Havana. A significant increase of this work happened after a 1993 law allowed the office to run its own businesses and reinvest the profits in preservation programs.

The structure of the City Historian’s Office led by the charismatic Eusebio Leal grew more complicated as the scope of businesses and tasks increased. By late 2000, it encompassed the city’s Master Plan office, which in turn included the San Isidro project in the southern tip of the old walled precinct. This project seeks the total revitalization of a historically poor neighborhood where the most notorious red-light district of Havana flourished in the early 1900s. The office also includes a negotiating group, the Plan Malecón for the comprehensive development (PERI) of the first fourteen blocks along Havana’s landmark waterfront promenade, and a mass media group with a radio station. Also under the City Historian were the departments of cultural heritage, architectural heritage, housing, architectural projects, and a workshop-school to train youngsters as skilled rehabilitation workers. It also has an economic department that includes accounting, investments, taxes, donations and cooperation, imports/exports, employment, and commercial.

The entrepreneurial system of the office comprises several business concerns: the Puerto Carenas construction company, two real estate agencies (Aurea and Fénix), Habaguanex (the initial commercial enterprise under the City Historian’s Office and still the most important), a nursery supplying plants and flowers, La Begonia; a tour-operator agency, San Cristóbal, and the Restoration of Monuments company that grew from the one that started preservation works on historic landmarks in Old Havana in the 1980s, according to a 1999 report by Patricia Rodríguez, “Desafío de una utopía / Challenge of a utopia. Plan Maestro de La Habana Vieja,” Ciudad/City # 4, Navarra.

The experience of the City Historian’s Office in Old Havana has been partially extended to other historic centers in Cuba like Trinidad, Santiago de Cuba and Camagüey. Once regarded as an impossible burden hindering the Cuban government, the office is now self-sustaining and even able to extend benefits to local residents through job creation and improvement of their living conditions: a demonstration of a fruitful convergence of cultural, social, environmental and economic interests. Culture-motivated city tourism can bring new life to central districts that were already abandoned, neglected or overlooked a century ago. This type of tourism—especially if properly disseminated—will have a less negative social and environmental impact. But a viable large-scale preservation of Havana’s enormous built heritage calls for the active participation of the local population, building a culture of cooperation within well-established neighborhoods. In the end, an empowerment of the residents through a flexible local economy should make as many people as possible capable of paying for themselves.

James Marston Fitch was one of the first scholars to indicate how the revitalization of historic centers could become a motor for the entire city economy. The economic success of the preservation program in Old Havana, and to a less extent in other Cuban historic sites, confirms this assertion. However, it also raises the question of how to use a historic site or building without destroying not only its physical values but also its intangible ones, like character and dignity. And this economic success also may encourage a review of the ethics of preservation and the search for authenticity—which is more challenging in younger centers that have undergone sharp transformations, like in America, than in older, consolidated historic centers, like Europe. Historic sites should be attractive and livable, but market-driven gentrification and tertiarization processes, plus a kitschy commercial approach to please mass tourists might ruin them even faster than neglect, poverty, or violence. A careful combination of pragmatic and cultural goals, like in Old Havana, might succeed in walking along the thin line between paralysis and disaster.

Winter 2002, Volume I, Number 2

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Tourism

Ellen Schneider’s description of Sandinista leader Daniel Ortega in her provocative article on Nicaraguan democracy sent me scurrying to my oversized scrapbooks of newspaper articles. I wanted to show her that rather than being perceived as a caudillo

Recreating Chican@ Enclaves

Centrally located between southern Colorado and northern New Mexico, is a hundred-mile long by seventy-mile wide intermountain basin known as the San Luis Valley. Surrounded on the east …

Tourist Photography’s Fictional Conquest

Recently, while walking across the Harvard campus, I was stopped by two tourists with a camera. They asked me if I would take a picture of them beside the words “HARVARD LAW SCHOOL,” …