The Public Face of Cyberspace

The Internet as a Public Good

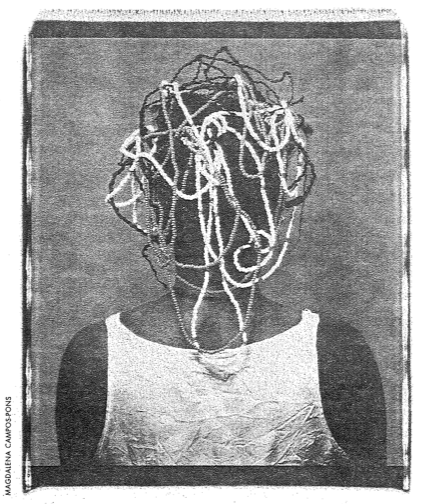

“Los Caminos,” 1996, from the “When I’m Not Hère, Estoy Alla.. ” series by Magdalena Campos- a Jamaica Plain artist. The Cuban-born artist is a former Bunting Institute Fellow.

Imagine a network that spans the world. A network that delivers — invisibly and inexpensively — the myriad bits of information that will undeniably be the key to prosperity in the 21st century. Imagine a network that links patients in rural areas of Latin America with doctors in the cities or even in foreign medical centers. Imagine a network linking poor students in Central America’s tiny mountain hamlets with trained teachers, and connecting farflung businesses with customers wherever they might exist. This network, of course, is the Internet.

In these scenarios and many others, the Internet acts as a virtual and virtuous public good. It incorporates the activities of all who wish to use it. It allows these users to interact without any rivalry in their usage. And it serves the greater good of the community in which it exists, easing information flows and creating layers of positive externalities. But does this world really exist? Can it deliver the lofty ideals that its adherents predict? In 1998, it is not quite clear. Yes, the potential of the Internet is obvious, but its capacity to function as a public good is not. Particularly in the developing world, the promise of a networked society may be more hopeful than real.

With cyberspace developing at breakneck speed, it is impossible to predict trends with any certainty. Yet it is also important to think about how countries, and particularly developing countries, will deal with this technical and sociological development. Should cyberspace be considered a public good, subject to government policy and regulation? What policymaking forum is most appropriate for this vast new territory? And how will rules of any sort be imposed on the unruly reaches of the Net?

By 1998 the Internet could truly be seen as a global medium-even, perhaps, as the global medium. Its connections crossed borders imperceptibly, linking markets and citizens in new and intriguing ways and destroying conventional notions of national borders. Continuing a trend made possible by phones and faxes and satellite dishes, the Internet promised to make information readily available to all corners of the globe. Cheaply, and without technological hassle, it promised to deliver to users whatever information they could find-and to link the purveyors of information to their potential consumers with a speed and an ease that had never before been realized. In the process, it also threatened to destroy many of the more conventional aspects of business, society and the state.

Both the promise and the threat rested on the basic power of information. By moving information so widely and freely, the Internet could remove the informational barriers that authoritarian states had long wielded over their citizenry. It could also put producers directly in touch with their would-be customers, dismantling the cumbersome chains of wholesalers, distributors and retailers that have customarily separated producers from their sales and added significantly to final product costs. In both the commercial and political spheres, therefore, the radical promise of the Internet was to dismantle existing chains of authority, giving citizens and consumers greater autonomy over their own decisions and-more poetically-their own fate.

Without the benefit of hindsight, it is difficult to evaluate the credibility of any of these promises, since their delivery rests so critically on the passage of time and the interplay of countless unpredictable factors. Yet thinking of these predictions in the context of public goods is an interesting (if perhaps non-obvious) point of departure.

Public goods, after all, are essentially a way of conceiving economic activity that falls somewhere between the state and the market. Discussion of public goods implies a concern for the societal impact of commercial activity or for the provision of social goods outside of normal commercial channels. All these attributes and all these issues exist in cyberspace. Indeed, many of the more radical promises put forth by the Internet’s most devoted proponents relate to the shifting boundary between private and public sectors, and to the provision of social goods by commercial forces.

The Case for the Internet as a Public Good

The definition of a public good is no easy matter. The two most-often cited attributes of public goods is that they are nonexcludable and their consumption nonrivalrous. Both of these attributes can be seen to apply to the Internet. Theoretically, any number of users can simultaneously interact in cyberspace. By ratcheting up the necessary physical infrastructure-adding servers, increasing telephone lines, building additional satellite capacity-new users can simply piggyback onto the existing system: it is almost infinitely expandable..

The parallel here to road-based highway systems is apt. Once the main structure has been constructed-the United States’ interstate system or Germany’s autobahn for the original highway; the NSF-supported backbone for this new Information Highway-new systems can be attached to this structure without tremendous difficulty. Local communities can build connecting roads to the interstate system; new users can access the Net through modems and phone lines. Unlike the older highway systems, though, this one is global. Users in, say, Colombia, can connect directly to Yahoo! or Microsoft Network. Their links to these U.S-based services, moreover, do not come at the expense of existing connections within the United States. Instead, the Colombian users are simply added into the system, expanding the network rather than constraining it.

It is this attribute of cyberspace that puts it, theoretically at least, into the category of public goods. So long as the Colombian user can gain access to a phone line, a computer, and a modem, he or she cannot easily be denied access to the Internet’s underlying architecture. The highway is there, it is open, and anyone with a direct connection can venture upon it. More formally, the use of the Internet’s myriad pathways is thus non-excludable. Likewise, its usage is also non-rivalrous, since the entry of the Colombians does not force any other users off-line. To the contrary, one of the Internet’s most-touted features is its very ability to bring together expanding communities of like-minded users. So the addition of the Colombia users to, say, a chat room on development in the Andes would presumably increase the value of the chat room to its existing users.

Cyberspace bears another attribute of public goods as well, since it has the capacity-perhaps even the natural inclination-to foster positive externalities, such as long-distance medical treatment. Expert doctors could be brought to “consult” in remote areas, reviewing patients they will never meet, conducting training for local health providers, even “assisting” through video links with operations or emergency procedures. The result would be better healthcare, at lower cost, for the local community and all who come into contact with it. Tele-education could likewise link students and teachers over what would otherwise be improbable distances, once again bringing high-quality services at very low cost.

Even at a purely commercial level, the Internet promises to create positive externalities, particularly in the realm of economic development. With access to the Net, small producers in remote locations can gain exposure in, and thus access to, wider markets. Rather than having to link themselves to intermediaries and retail distributors, producers can advertise their wares directly on the Net, attracting the kind of consumers most likely to purchase a particular product. If such online sales spur significant commerce-and online sales in general are predicted to grow to anywhere between $6 billion and $130 billion by the year 2000-they should act to spur economic growth and its accompanying benefits wherever they occur.

Yet the tremendous possibilities of cyberspace must not blind governments or their citizens to the costs that are likely to accompany the growth of this new territory.

Governments that want to reap the tremendous potential of cyberspace in tele-medicine and tele-education, for example, will have to expend considerable resources to do so-or else find some means of harnessing the private sector to service the public good. Citizen concern about privacy issues and children’s access to pornography or particular political or religious views will undoubtedly manifest themselves in public debate, and eventually in public policy. Governments will need to find some means of squashing the transfer of “bad” information without restricting the flow of “good”.

Moreover, the fundamentally international nature of cyberspace dictates that any Internet policy will need to be multilateral, spanning all countries in which the relevant activity occurs. Global coalitions will need to be created and global consensus arrived at-even though the Internet is still in its infancy and countries vary widely in their use and familiarity with it. Developing countries in many ways have the greatest stake in the orderly and open development of the Internet. They cannot afford to have information in cyberspace restricted entirely to private enclaves or to have this flow of information slowed by a priority system that works against poorer users. They also need desperately to create the physical infrastructure that will bring the Internet to the doorsteps and desktops of their citizens. These developing countries, such as those in Latin America, risk exclusion from a policy that will in all likelihood be global in scope.

Latin American and other developing nations need to recognize the importance of building negotiating links not just with other nations, but also with the private groups that are increasingly helping to shape the rules of cyberspace.

Conceiving of the Internet as a public good helps at least to point policymakers in an appropriate direction. The Net is undeniably a boon for private business and a revolution in communications. It is also, though, a powerful medium capable of delivering-or restricting-significant societal benefits. Thinking of it in this way, and probing policy options along these lines, are the first steps towards harnessing this tremendous power.

Winter 1999

Debora Spar is an Associate Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School. This article was adapted from her chapter, “The Public Face of Cyberspace: The Internet as a Public Good.” in Global Public Goods: International Cooperation in the 21st Century, Inge Kaul, Isabelle Grunberg, and Marc A. Stern, eds. New York: Oxford University Press, available late March, 1999. Funding for the chapter was provided by the United Nations Development Program.

Related Articles

Linking Latin America

I have captured images of such seemingly disparate subjects as Mennonite immigrants to Mexico, Latina contestants for Selena standings, the Pope in Cuba, and traditional Sunday serenatas…

A Violence Called Democracy

As any journalist or diplomat who has spent time in Guatemala will attest, no group there is more difficult to penetrate than the Guatemalan Armed Forces. As much a caste as an institution, the…

Researching Latin America

The instant outpouring of Web information on the Pinochet case got me to thinking about communications on my first trip to Chile during the Allende presidency. I was armed for Ph.D…