Things I’ve learned about Indigenous education and language revitalization

Language minoritized learners are those who bring to school languages or ways of speaking other than the dominant or official school language, including refugees, immigrants and speakers of non-standard or Indigenous languages. It is not necessarily about being a minority in numbers, but about being minoritizedby inequality of status and inequity of treatment, often across multiple generations. I have been interested in the experiences of alllanguage minoritized learners and communities, but perhaps most of all Indigenouslearners and ways of speaking, doing, being, ever since I lived and worked with Quechua speakers in the South American Andes in the 1970s.

Ethnographers’ stories are the fruit of painstaking, detailed, and often long-term participant observation, interviewing and document collection in specific places, with the goal of understanding, analyzing and interpreting peoples’ ways of speaking, doing, being, thinking and feeling in that place. Ethnographers’ stories are also informed by the ethnographer’s own ways of speaking, doing, being, thinking and feeling, as well as by a store of theoretical and empirical research – in my case my own and others’ research on bilingualism and bilingual education, sociolinguistics, anthropology of education, language policy and planning, Indigenous language revitalization, and my conceptual framework, the continua of biliteracy (Hornberger 2002)

These stories, which I have published earlier and retell here, come from the Andean highlands and the Amazonian rainforest across several decades, and the things they’ve helped me learn about are:

(1) ideological and implementational spaces: National multilingual language education policies may open up ideological and implementational spaces for Indigenous education; but it is local actors who fill those spaces when they appropriate, interpret, and at times resist OR expand beyond policy initiatives (Hornberger 2005).

(2) multilingual multimodal language ecologies: Indigenous learners draw on a repertoire of communicative resources across their languages, including speaking and writing as well as graphic representations, gesture, movement, digital communication and more.Multimodal, multilingual classroom ecologies potentially strengthen participants’ communicative repertoires while simultaneously fostering peer interaction and cooperative learning (Hornberger 1998).

(3) reclaiming Indigenous ways: Indigenous education affords spaces for reclaiming, reaffirming and revitalizing Indigenous ways of speaking, doing, being, thinking and feeling (Hornberger 2009).

(4) language and voice: When classroom practices are effective in fostering dynamic development of Indigenous learners’ language and literacy, it is perhaps because of using their language in ways that mediate voice, through dialogical engagement with others, meaning-making, access to wider discourses and taking an active stance (Hornberger 2006).

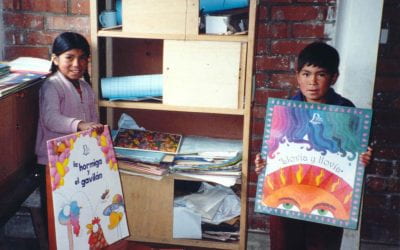

Ideological and implementational spaces

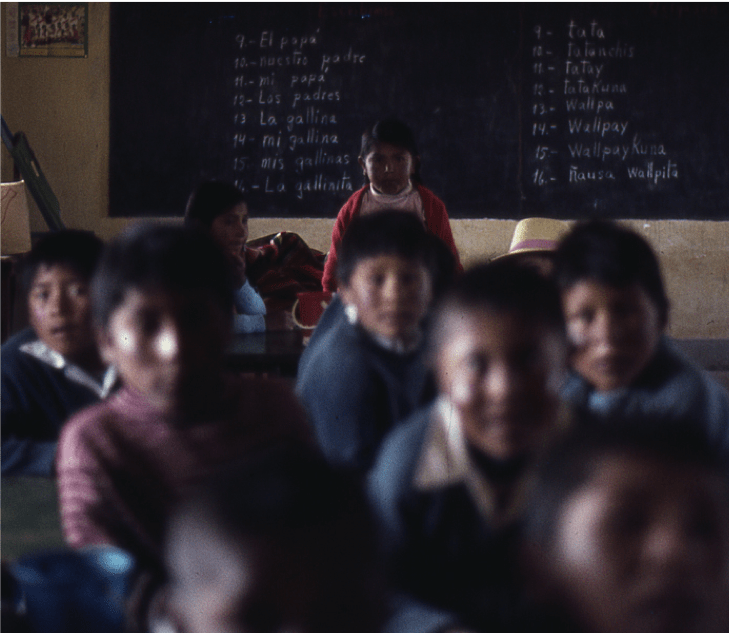

At Kayarani school, located in a highland valley about an hour’s drive from the city of Cochabamba, Bolivia, a new building had been inaugurated the year before I visited in August 2000. Classrooms were welcoming, with tables and chairs set up for group work, a welcome change from ubiquitous rows of three students per pupitre“desk” facing forward to the teacher in the traditional highland school. Teacher Berta had been there three years, implementing bilingual intercultural education under the 1994 Bolivian national education reform. Handmade posters in Quechua decorated her classroom, showing models of a story, a poem, a song, a recipe, a letter, as well as both the Quechua and Spanish alphabets. The class newspaper, Llaqta Qapariy“Voice of the People,” also hung on the wall and featured an article in Quechua written by student Calestino about farmers’ wanting better prices for their potatoes, their community’s subsistence. The 80-book library provided by the Reform through UNESCO auspices included six Big Books in Spanish, three based on Indigenous oral traditions. The Big Books are approximately 18” by 24,” with large print text and colorful illustrations, such that the pictures can be seen by the whole class if the teacher holds the book up in front of them. Two children noticed my interest in the Big Books and gleefully held them up for a photo when the rest of the class left for recess.

Bolivia’s 1994 education reform sought to implant bilingual intercultural education (EIB), nationwide, incorporating all 30 Bolivian Indigenous languages, beginning with the three largest—Quechua, Aymara and Guarani. The new law had massively expanded the reach of EIB fromaround100experimental schools in the early 1990s to almost 3,000 schools by the early 2000s, reaching22% of the primary school population and yielding higher rates of graduation and lower school desertion rates. The reform clearly opened ideological and implementational spaces for the practice of multilingual Indigenous education, as at Kayarani where teacher Berta actively embraced and creatively put into practice the Bolivian Reform’s multilingual pedagogy. But in other rural Bolivian schools, untouched stacks of the reform’s texts remained in locked cabinets in the director’s office and little effort was made to implement EIB. Top-down policies may open up ideological and implementational spaces; but it is local actors who fill those spaces when they appropriate, interpret and at times resist OR expand beyond policy initiatives.

Multilingual multimodal language ecologies

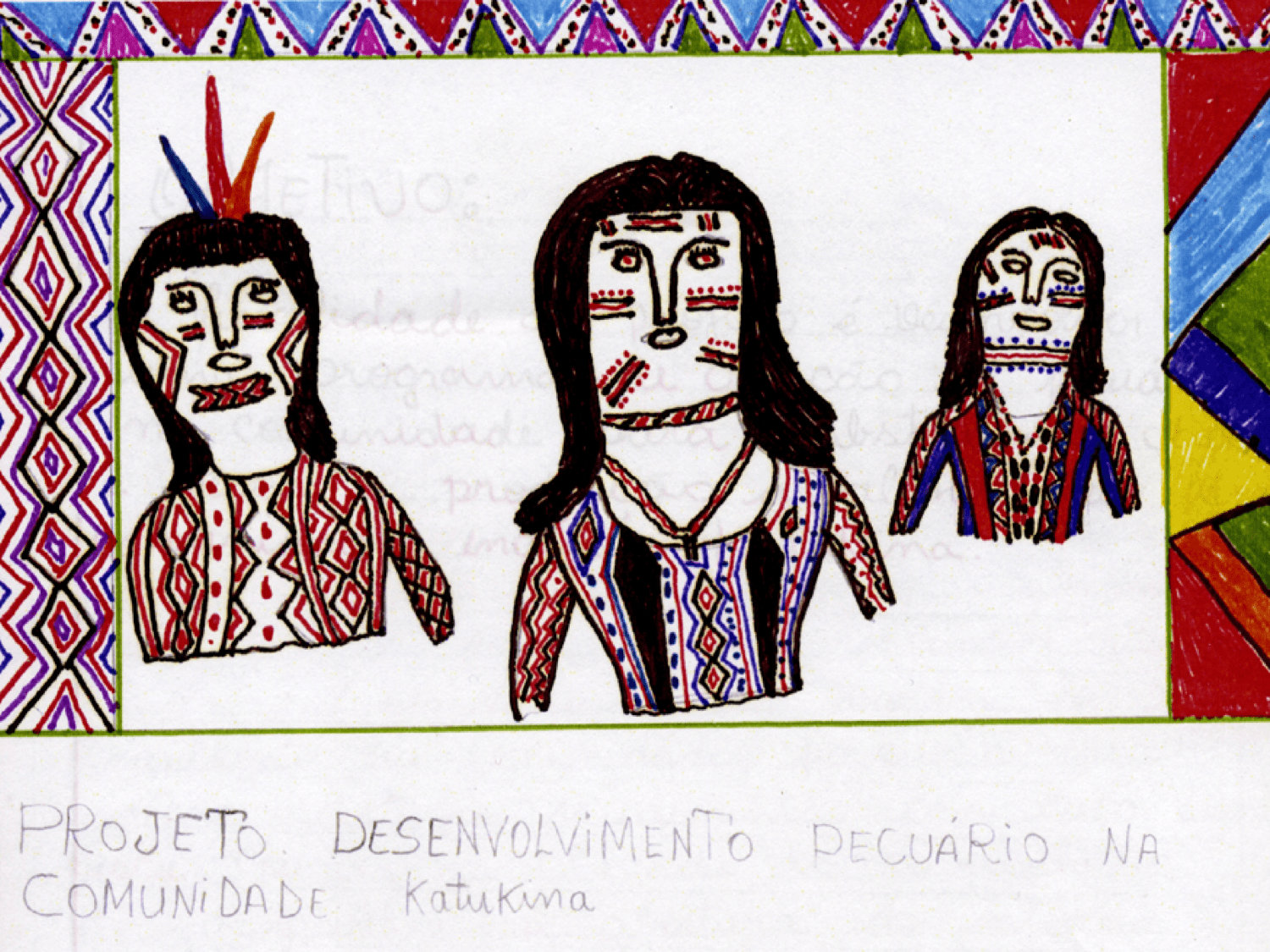

Since 1983, an annual Indigenous teacher education course sponsored by the Comissão Pró-Indio do Acre (CPI) in Rio Branco has been held during the southern hemisphere’s summer months (January-March) in the Amazonian rainforest of Brazil. At the 1997 session I attended, there were some 25 profesores indios “Indigenous teachers,” representing eight different ethnic groups whose languages varied in their vitality, some with about 150 speakers and others several thousand. A striking feature of the course was the mutual multilingual understanding among the profesores. Their Indigenous languages were not only encouraged and used as medium and subject of instruction in the course and later in their own schools, but also the profesores encouraged and exchanged among each other across their different languages. Even if they did not necessarily speak or understand all the other languages spoken and written by their peers, they read, listened to and looked at each other’s work. To facilitate mutual understanding, they at times used Portuguese as lingua franca, at times drew on the geometric designs that were an integral part of their writing and at times simply relied on their shared intra/inter-ethnic experiences.

The multimodal, multilingual, mutual comprehension was particularly striking given the great diversity of languages in the group and the salience of multimodal drawing and geometric design in their writing practices. Each written assignment bore the complex and colorful geometric designs and maps that are, as Brazilian scholars Nietta Monte and Lynn Mario Menezes de Souza demonstrate, not merely illustrations to accompany the alphabetic text, but integral complements to it; and these multimodal expressions contributed to the Indigenous teachers’ mutual understanding across language differences as well as to the development of their writing in those languages and in Portuguese. The multimodal, multilingual language ecologies characterizing language learning and teaching practices in spaces like these potentially strengthen each individual participant’s communicative repertoire while at the same time fostering peer interaction and cooperative learning.

Reclaiming Indigenous ways

PROEIB-Andes at the University of San Simón in Cochabamba, Bolivia, is a master’s program in bilingual intercultural education for Indigenous students, created in the ideological and implementational space of Bolivia’s 1994 reform. In September 2004, I did a series of workshops on ethnographic research methods with the fourth cohort’s 42 students from six Andean countries and at least a dozen different Indigenous language backgrounds. For our final unit, I told them about the Indigenous research agenda proposed by Māori researcher Linda Tuhiwai Smith in her 1999 book Decolonizing Methodologies, in which she talks in terms of four tides or conditions in which Indigenous people live—survival, recovery, development and self-determination; four directions or processes through which they move—healing, decolonization, mobilization and transformation; and 25 projects Indigenous people undertake, such as reclaiming, renaming, remembering, revitalizing and networking. Smith’s metaphor of tides is very much based in a Māori island-ocean ecology, so I wasn’t sure how this would go over with the group of mostly highland Andean Indigenous educator-researchers I was working with.

It turned out they were extremely attentive, avidly taking notes and showing clear moments of resonance and response, for example when I mentioned Smith’s “connecting”and her example of reinstituting the traditional Māori practice of burying the afterbirth after the child is born, the word for both being the same in Māori. Students again resonated when I mentioned “renaming” places and people with their original Indigenous names, and they spontaneously came up with their own examples e.g. Amazonian Aguarunas reclaiming their own name, Awajun. At the end, I asked the group ¿Qué les parece? “What do you think?” and they immediately replied Estamos con la Linda! “We’re with Linda!” — resoundingly endorsing the framework and embracing the researcher on a first name basis.

These Indigenous educators participating in the workshop resonated with Linda Smith’s notion of connecting people to each other and to the earth. When, in later interviews, I asked what it means to them to be Indigenous, the first and most prominent responses were about living close to the land, speaking one’s native language and experiencing discrimination by others. These themes, about affirmation of one’s own ways of doing, being and speaking— and at the same time experiencing discrimination by others for those very practices, were foremost in the collective story of these individuals’ experiences of and reflections about being Indigenous.

Envisioning and building an Indigenous future was another theme that resonated with the Andean educators, closely linked to reclaiming their locally rooted practices, renaming their world and revitalizing their Indigenous identities. Moisés, a Peruvian Aymara, summed this up in an interview with me:

“For me, being Indigenous means identifying with my ethnic people, our past, our history, our worldview, our language; in the present, working to reclaim our rights, being actively committed; and in the future, projecting that our ethnic people might have a future with equality of opportunities with other peoples of our country.”

Moisés’ commitment is to use his graduate studies to improve the lives of his people, drawing on their collective past to project toward the future. Fully aware of the enormous structural obstacles and historical oppressions they face, through both lived experience and intellectual study, he and his peer Indigenous educators consciously choose the path of transformational resistance – often at great personal cost, in the sense Bryan Brayboy highlights in the experience of American Indian university students in the United States. The PROEIB educators opt to, as one of them puts it, aprovechar el espacio que el Estado nos da“exploit the space the nation-state gives us”—through multilingual education—to work toward the future equality and dignity of their people and thereby of all people.

Language and voice

Neri Mamani grew up in rural highland Quechua communities of southern Peru. In 2005, when I met her, she was a bilingual intercultural education practitioner enrolled at PROEIB-Andes. In a four-hour interview with me, she narrated her development as teacher, teacher educator, researcher and advocate for Indigenous identity and language revitalization, traversing urban, peri-urban and rural Andean spaces. My paper titled in her words “Until I became a professional, I was not, consciously, Indigenous” (Hornberger 2014)tells how Neri and her peers’ recognizing, valorizing and studying the multiple and mobile linguistic, cultural and intercultural resources at play in their own and each others’ professional practices around bilingual intercultural education enabled them to co-construct an Indigenous identity that challenges deep-seated social inequalities in their Andean world. Neri insisted that use of Quechua is a highly visible marker of Indigenous identity and that the strengthening of both language and identity depends on daily use of Quechua as a viable language of communication, not only in educational spaces, but beyond: “If we don’t use our language, talking on the phone, writing on the Internet, riding public transport and talking there, going to the market speaking Quechua, going to the supermarket and speaking Quechua, if we don’t do it, who’s going to do it? Language is perhaps the most noticeable, most visible, strongest marker of cultural identity.”

Crediting the PROEIB master’s program for opening implementational and ideological spaces for her and her peers to pose questions such as “Who after all is Indigenous?” Neri said: “…we never would have arrived at these commentaries, these reflections, never would have begun to perceive these things, if we had not done the reflection we do, or read all the bibliography we read. Never. We would not have questioned at all.”

Neri’s reflections on how PROEIB’s classroom and program practices were effective in fostering dynamic development of PROEIB Indigenous educators’ language and identity, brought me back to my Ph.D. research on the Peruvian altiplano in the 1980s where I had observed a little seven-year-old girl in both classroom and home settings who rarely, if ever, spoke in class, despite being in a bilingual Spanish-Quechua classroom.

Yet, at home, she was something of a livewire, talking non-stop to me in Quechua, telling me all about the names and ages of her whole family, showing me the decorations on the wall of her home, the blankets woven by her grandmother, borrowing my hat—all this while she jumped on the bed, did somersaults, cared for her two baby brothers, and so on.

Then, as now, it struck me that this little girl, whom I call Basilia, lost her voice at school and found it at home and that use of her own language in familiar surroundings was key in the activation of her voice. Voice was not just about using Quechua in the classroom, but being in active dialogue with her environment. Language and voice are related, but it is also important to distinguish between them, as my mentor Richard Ruiz wrote in 1997: “Language has a life of its own–it exists even when it is suppressed; when voice is suppressed, it is not heard–it does not exist. To deny people their language….is, to be sure, to deny them voice; but, to allow them ‘their’ language … is not necessarily to allow them voice.” When, as in the case of the PROEIB master’s program, classroom practices are effective in fostering dynamic development of Indigenous learners’ language and literacy, it is perhaps because of using their language in ways that mediate voice, expressed through dialogism, meaning-making, access to wider discourses, and taking an active stance (Holland and Lave 2001).

Indigenous educators’ experiences in language revitalization, as told in these stories, are both profoundly different from and profoundly the same as that of multilingual educators more generally. The contested and highly politicized nature of Indigenous education and language revitalization is familiar to those engaged in multilingual education efforts in minoritized language communities everywhere. Yet, these stories of Indigenous educators and language activists filling up and expanding on ideological and implementational spaces opened up by top-down policies; enacting multimodal multilingual languagelearning and teaching practices;reclaiming Indigenous ways of speaking, doing, being, thinking and feeling; and activating Indigenous voices speak eloquently of the possibilities for constructing more just and democratic societies in our globalized and intercultural world. It is in their advocacy for the oppressed—and Indigenous peoples are arguably the most deeply oppressed of all peoples—that Indigenous education and language revitalization are so politically controversial and at the same time why they offer so much hope for a better and more just future for all peoples.

Nancy H. Hornberger is a Professor at the University of Pennsylvania

Related Articles

Ghosts of Sheridan Circle

Targeted killing of political enemies—assassinations—is thankfully rare in the United States. The most famous such assassination occurred in Washington, DC. And it was committed by a close ally of the United States. In September 1976, Chile’s Pinochet dictatorship…

Bilingualism: Editor’s Letter

It was snowing heavily in New York. It didn’t matter much to me. I was in sunny Santo Domingo with my New York Dominican neighbors on the Christmas break from school. I learned Spanish from them and also at the local bodega, where the shop owner insisted I ask…

Two Wixaritari Communities

English + Español

I first arrived in the wixárika (huichol) zone north of Jalisco, Mexico, in 1998. The communities didn’t have electricity then, and it was really hard to get there because the roads were simply…