Tracking Crocodiles in Markets, Farms, and Mangroves.

Study of Exotic Animals in Archaeological Contexts

While on the run, Indiana Jones once said “If you want to be a good archaeologist, you have to get out of the library.” His statement incensed me. We archaeologists coexist among earth, books and treasures! Much to my chagrin, the Hollywood hero was right. Archaeology is not just limited to classrooms, libraries, ruins or the thousands of materials we analyze. Our investigations are enriched through other sciences, disciplines and experiences.

When I decided to study the crocodile remains found in the excavations of the Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlan (former seat of the Mexican empire from 1325 to 1521), in what is now Mexico City, I was aware that I’d have to review codices and chronicles from the 16th to 18th centuries; I knew that I was going to consult books, drawings, reports, and spend long hours examining bones in the museum’s storage room. I never imagined that I would have the opportunity to pat crocodiles, capture them or discover the hidden secrets of fur and taxidermy. I never expected that this research could lead me to biology, ethnology or ethnozooarchaeology.

I discovered that analyzing fauna within archaeological contexts is fascinating, especially when it involves exotic species. Crocodiles are particularly interesting, semi-aquatic reptiles covered by dermal shields with a threatening snout supplied with sharp teeth. They are so spectacular that, whether through feared or worshiped, they have been incorporated as part of the daily and religious life of multiple cultures, including Mesoamerican ones. The Mexica called them acuetzpalin “water lizard,” but it was known as cipactli “thorny being,” when combined with other animals to form a creature that starred in creation myths, related to the beginning of time and the world. Its anatomy gave way to varied metaphors: its scaly back was compared to the rough surface of the earth, and its snout represented the cave, access to the underworld.

In the Templo Mayor, 21 crocodiles and eight pendants made with teeth of this reptile have been exhumed. Most of them were subjected to complex treatments to preserve their skin. They lay in the tomb of a dignitary, in rich deposits that configured miniature representations of the universe and in offerings that symbolized creation myths.

Offering 61 of the Templo Mayor, photo by Salvador Guilliem; remains of crocodile skin from Offering 61, photo by Mirsa Islas.

However, since these reptiles inhabit tropical regions far from the center of Mexico, obtaining them must have required great effort. The process began with their selection, followed by their hunting or capture. Then, dead or alive, they were transported to Tenochtitlan from the Pacific, the Gulf of Mexico or the Caribbean Sea. Those who carried out this task traveled a distance from about 125 to 430 miles. The journey probably lasted several days, during which time they may have had to deal with the challenges of hazardous terrain, inclement weather or dangerous animals. If the crocodiles arrived alive, they would be confined to the city’s zoo.

To learn about tracking, hunting, trapping techniques, animal handling and skin making, I consulted specialized articles, attended a reptile manipulation course, witnessed the capture of crocodiles in the wild, talked to a former alligator hunter, reviewed pelt collections and observed how two taxidermists made them. This allowed me to recognize the complexity of each process, make comparisons with historical chronicles, formulate hypotheses and, of course, better understand the archaeological materials.

I also inquired about the importance of crocodiles in pre-Hispanic times and modern times, as many of the uses and beliefs have endured over the centuries. Some communities still believe that the earth is formed by the back of the reptile. In addition, people still use as a food product, in the clothing industry, for magical purposes and for medical remedies.

I want to share some of my experiences studying these animals. This interdisciplinary approach helped me deepen my research and to conclude the analysis, but also allowed me to explore another dimension that is not available in books. It led me to appreciate crocodiles through different lens.

Looking for skins, bones and fangs

To capture crocodiles, I accompanied a group of biologists led by Pierre Charruau, who studies the population, reproduction and health of these reptiles in Banco Chinchorro, Quintana Roo, an island in the middle of the Caribbean Sea with a paradisiacal environment, absolutely mind-blowing. The place is surrounded by a coral reef inhabited by thousands of multicolored organisms with the most diverse shapes. In the deepest blues of the ocean lie numerous ships stranded against the reefs; nature has invaded them with marine fauna.

The land on the island was just as spectacular. Iguanas basked in the warm sun and observed their surroundings from the tops of palm trees. The songs of birds could be heard as they crossed the sky, while crocodiles roamed the mangroves or perched indolently on the soft sand of the beach.

The night was tinged serene, and in the darkness, two biologists, a vet and I, boarded a canoe to venture through the labyrinthine paths of the swamp. This would be the scene of one of the briefest nights of my life, among the dense underbrush, the glimmer of the stars in the shallow waters, and the trills of a swarm of insects, muffled only by the fluttering of crocodiles against the water as they were caught.

Pierre was ahead, standing at the bow with the light of his lamp carefully inspecting the waters. Suddenly, two small marbles flashed in the distance. Although the crocodiles were almost submerged, their eyes betrayed them. With extreme stealth, we moved toward them and, once we reached a safe distance, Pierre threw a rope at them. When trapped, these reptiles spin around so vigorously that they can dislocate the arms of their captors. Fortunately, after some resistance, the animals relented and we were able to carefully lift them into the boat.

Once in the canoe, the crocodiles’ eyes were covered and their legs tied. Not only to protect us from attacks, but also because when crocodiles get nervous, they can go into glycemic shock and die immediately. None were injured and after several tests, all were returned to their swamp.

Trapping and handling of a crocodile; a juvenile crocodile, Banco Chinchorro. Photos by the author.

Along the way, we also found some hatchlings camouflaged among plants that floated with them. By extending my hand, I was able to grab one to admire it more closely. The next day—after sleeping for a few hours—we headed to a part of the island with fishermen’s huts supported by stilts in the middle of the sea, where a spectacular crocodile almost nine- feet-long was roaming the crystal-clear waters. I was captivated and immediately realized the analogies made by the pre-Hispanic cultures. After an incredible struggle between the animal and three experienced men, the reptile was trapped, tested and subsequently released.

Banco Chinchorro and an enormous crocodile captured by biologists. Photos by the author.

Upon my return to Mexico City, I continued to analyze the archaeological materials and faced great complications. I didn’t know how to classify certain bones, which were right or left, nor how the plates on their backs were disposed. I turned to specialized manuals, osteological collections and consulted with biologists, but I lacked answers. Bone studies of wildlife are rare. The solution was to get a dead specimen, flesh it, obtain its remains and to understand the anatomy. Clearly, not a simple task.

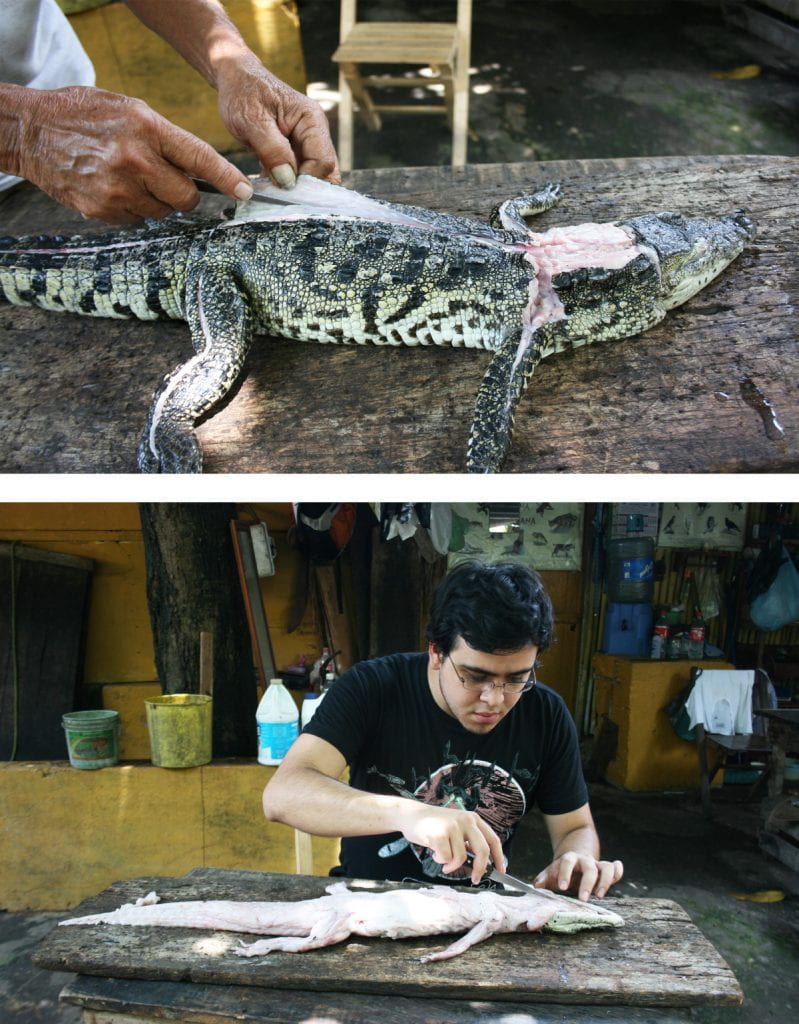

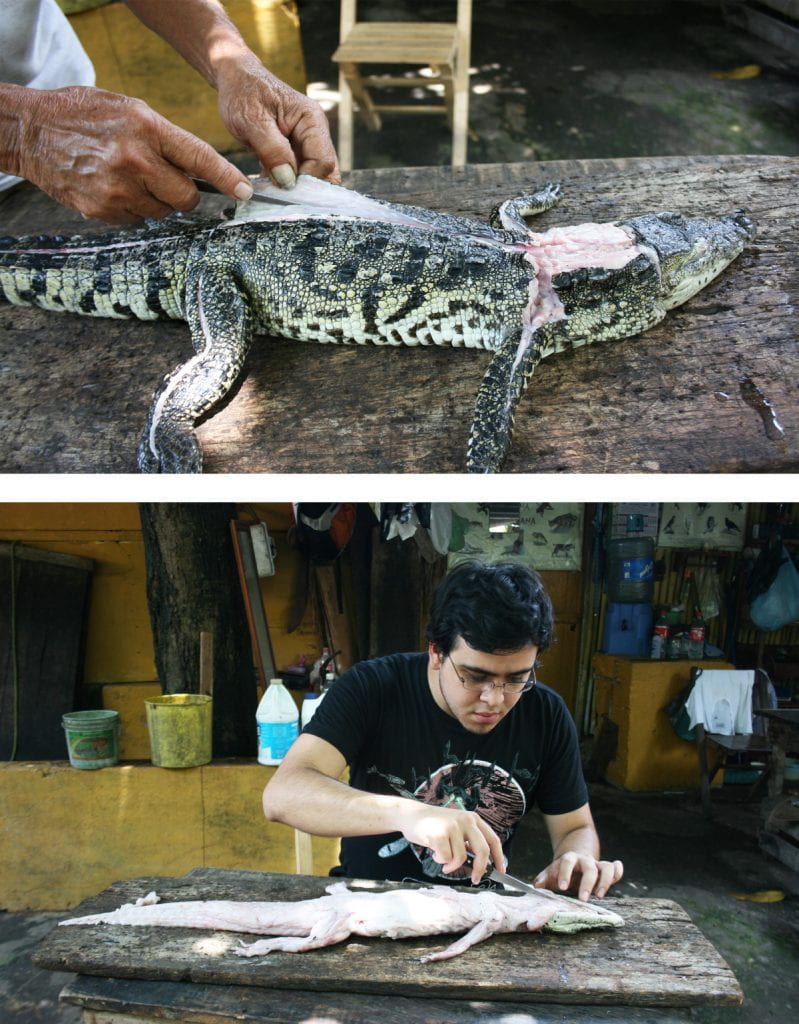

My second story begins with exploring exotic food markets and contacting crocodile farms, sustainable places that don’t decimate populations. By chance, a friend of my boyfriend Ernesto’s father, found a taxidermist on a farm in Chiapas. An alligator had been killed in a fierce fight with a larger opponent. The next day Ernesto and I caught a flight to southern Mexico, determined to recover the bones.

While we fleshed the animal with the taxidermist’s knives, he told us how he hunted caimans—a relative of crocodiles—in the seventies. He usually went with two other trappers. To trace the alligators, the men followed the tracks left on the ground or imitated the vocalization of the young to entice the adults to the rescue. In a few hours they obtained up to 80 specimens, and they would end after gathering about 400 alligators. They used shotguns and harpoons, but if the reptiles were not so large, the men preferred to kill the animals by hitting them on the head. In this way, they avoided damaging the body’s skin. Coincidentally, one of the crocodile pelts from the Templo Mayor has two fractures in the skull, one produced before its death and another that didn’t heal, possibly an indicator of how it died.

Hunting crocodiles is not easy, but capturing them alive is an even more difficult feat. Surely in pre-Hispanic times it was done by experts who knew the environment, the behavior of these creatures, as well as proper tools and the courage to face the reptiles.

Skinning and fleshing of a crocodile. Photos by the author.

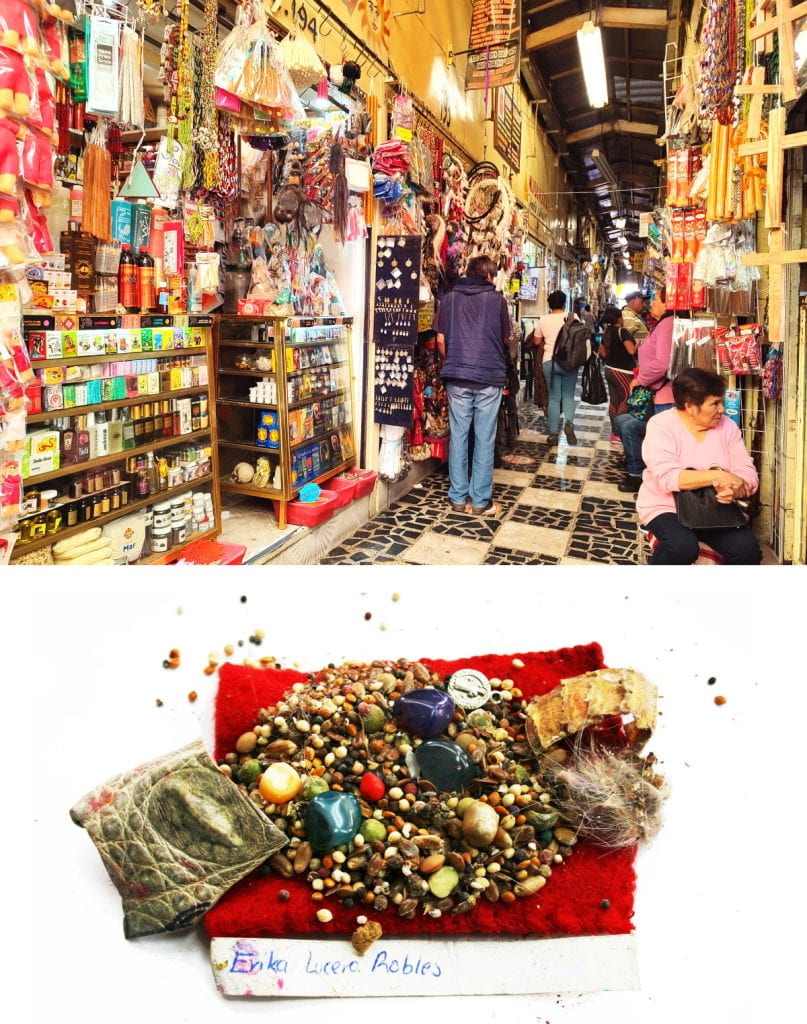

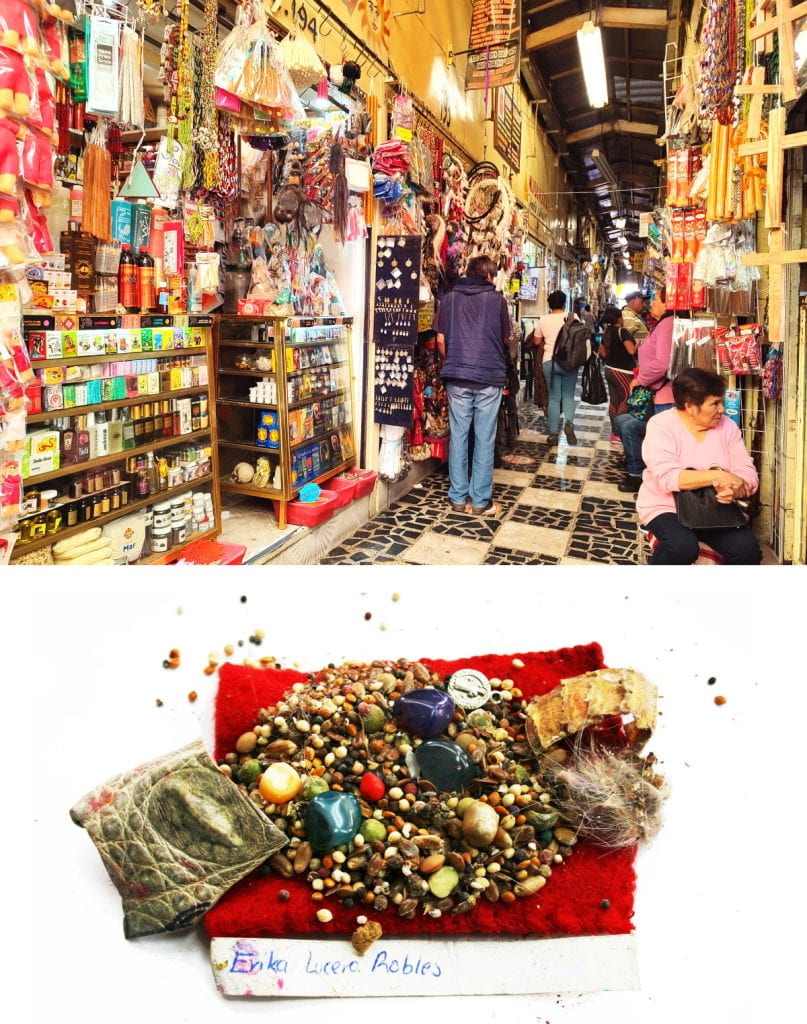

My last story takes place in the Sonora Market, Mexico City, famous for selling esoteric items. The narrow aisles have a heady combination of smells of herbs, incense and copal. You can see sculptures of saints, lotions and potions to fulfill the most peculiar requests, such as love tonics, which are the most desired. In each stall hang candles of all sizes and colors, voodoo dolls, any kind of odd amulets and animal remains: feline skins, eagle feathers, goat legs and horns, and spiders in jars.

Witch doctors at the market told me that certain parts of the crocodile possess powers: the paws are used in “special ways” that they didn’t want to detail. The teeth and plates serve as protection and good luck, so several of them are part of complex amulets, such as one that a shaman made for me with a crocodile dermal plate, snake skin, ocelot hair, a small saint, many quartz stones and different species of seeds. After adding a piece of paper with my name and birthday, the man sprinkled everything with a potion, then put it all in a little red bag, assuring my good fortune.

I kept walking through the corridors and, although the atmosphere was eerie, I found it mesmerizing. In some corners there were giant figures of La Santa Muerte, the Saint of Death who, despite being repudiated by the Catholic Church, appears sumptuously dressed and adorned, surrounded by candles, flowers and gifts from her devotees in exchange for their petitions or in gratitude for their demands.

But in this place, it is impossible to cease to be amazed. When I asked for crocodile teeth, the merchants would often gladly offer fangs from other animals. Until, on one occasion, when I made my recurring request, the seller went into his store for a moment and took out something hidden from view, a large plastic jar full of little pieces, grabbed a fistful and placed a few in the palm of my hand. I was horrified, they were human teeth: molars, incisors and canines. After I nervously gulped, I gently returned the pieces and left with a thousand questions running through my head: how did he get so many? Does he loot graves?

The Sonora Market and an amulet with a crocodile dermal plate. Photos by the author.

It is true that information often transcends books, but the work of archaeologists is less like the adventures of Indiana Jones and more like the investigations of Sherlock Holmes. We pursue details and evidence that, as clues, help us to put together a puzzle to unravel the past. During excavation, as in a crime scene, the materials are carefully cleaned while avoiding moving them; we take numerous photos, make drawings and describe the position and orientation of each element. This helps us to reconstruct and solve the original arrangement of the objects.

We put down our trowels and put on our robes to carry out various analyses in the laboratory. In my case, it was necessary to identify the species, estimate age and size; describe the health conditions and the treatments made to the animals. At the same time, invaluable bibliography was consulted regarding the symbolism and use of crocodiles.

Occasionally, archaeology takes us along unexpected paths, lets us to cross its borders, study from other sciences and face experiences that enrich our investigations. Getting involved in the capture of crocodiles, learning from biologists and a former hunter, observing the techniques of preserving pelts and fleshing a crocodile, allowed me to glimpse the complexity required in the selection, hunting, modification and transfer of these reptiles from the tropical zones to central Mexico, where with the precision demanded by the ritual, they were placed in offerings that recreated the world. We never get all the answers, but looking for them is an opportunity to navigate mangroves, unravel spells or wield knives.

Rastreando cocodrilos en mercados, granjas y manglares.

Del estudio de animales exóticos en contextos arqueológicos

Por Erika Lucero Robles Cortés

Alguna vez dijo Indiana Jones mientras se daba a la fuga “Si quieres ser un buen arqueólogo, tienes que salir de la biblioteca”. Al escuchar tal afirmación me encolericé: ¡los arqueólogos coexistimos entre tierra, libros y tesoros! Muy a mi pesar, el héroe de Hollywood tenía razón. La arqueología no se limita a las aulas, las bibliotecas, las ruinas o a los miles de materiales que analizamos. Enriquecemos nuestras investigaciones a través de otras ciencias, disciplinas y experiencias.

Cuando decidí estudiar los restos de los cocodrilos encontrados en las excavaciones del Templo Mayor de Tenochtitlan (antigua sede del imperio mexica de 1325 a 1521), en la actual Ciudad de México, estaba consciente de que revisaría códices y crónicas de los siglos XVI al XVIII; que consultaría libros, dibujos e informes y estaría largas horas en la bodega del museo examinando huesos. Nunca imaginé que tendría la oportunidad de acariciar cocodrilos, de capturarlos o que descubriría los secretos de la peletería y la taxidermia. Tampoco tenía idea que la investigación me conduciría a la biología, la etnología o la etnoarqueozoología.

Indudablemente, analizar la fauna de contextos arqueológicos es fascinante, más cuando se trata de especies exóticas, como los cocodrilos, reptiles semiacuáticos cubiertos por escudos dérmicos, con un amenazante hocico abastecido de agudos dientes. Son tan espectaculares que, temidos o adorados, han sido incorporados como parte de la vida cotidiana y religiosa de múltiples culturas, incluidas las mesoamericanas. Los mexicas lo nombraban acuetzpalin “lagartija de agua” o cipactli, “ser espinoso” cuando se combinaba con otros animales para formar una criatura que protagonizaba los mitos de creación, vinculándose al inicio del tiempo y del mundo y, cuya anatomía daba lugar a las más variadas metáforas: su escamosa espalda se comparaba con la agreste superficie terrestre y su hocico representaba a la cueva, un acceso al inframundo.

En el Templo Mayor se han exhumado 21 cocodrilos, además de ocho dientes convertidos en pendientes. La mayoría de los individuos fueron sometidos a complejos tratamientos para preservar sus pieles. Yacían tanto en la tumba de un dignatario; en ricos depósitos que configuraban representaciones en miniatura del universo y en ofrendas que simbolizaban mitos de creación.

Ofrenda 61 del Templo Mayor, foto de Salvador Guilliem; restos de piel de cocodrilo de la Ofrenda 61, foto de Mirsa Islas.

Sin embargo, ya que estos reptiles habitan zonas tropicales lejos del centro de México, su obtención debió requerir magnos esfuerzos. El proceso iniciaba con la selección, seguido de la caza o captura efectuada por experimentados cazadores. Posteriormente, vivos o muertos, eran trasladados hasta Tenochtitlan desde el Pacífico, el Golfo de México o el Mar Caribe. Es decir, quienes llevaban dicho encargo recorrían una distancia de entre 200 y 700 kilómetros. La travesía seguramente duraba varios días en la que quizá se enfrentaban con los incidentes del relieve, las inclemencias del clima, animales peligrosos, entre otras eventualidades y, si acaso los cocodrilos llegaban vivos, serían confinados al zoológico de la ciudad.

Con el objetivo de conocer de las técnicas de rastreo, caza y captura; del manejo de los animales y la manufactura de las pieles, consulté artículos especializados, asistí a un curso de manipulación de reptiles, presencié la captura de cocodrilos en vida libre, conversé con un ex cazador de caimanes, revisé colecciones de pieles y vi cómo dos taxidermistas las elaboraban. Esto me permitió reconocer la complejidad de cada proceso, establecer comparaciones con las crónicas históricas, formular hipótesis y, en definitiva, comprender mejor los materiales arqueológicos.

Asimismo, indagué de la importancia de los cocodrilos en la época prehispánica y actual, pues muchos de los usos y creencias han perdurado a través de los siglos. En diferentes comunidades todavía se piensa que la tierra está formada por la espalda del reptil y aún se benefician de él como producto alimenticio, en la industria del vestido y para fines mágicos o remedios médicos.

En este texto relato algunas de las experiencias que tuve al estudiar estos animales, las que no sólo me ayudaron a profundizar en mi investigación y a concluir con el análisis, gracias a ellas conocí otra dimensión que no está disponible en los libros, las que me permitieron apreciar a los cocodrilos con otros ojos.

En busca de pieles, huesos y colmillos

Para capturar cocodrilos, acompañé a un grupo de biólogos liderados por Pierre Charruau, quien estudia la población, reproducción y salud de estos reptiles en Banco Chinchorro, Quintana Roo, una isla en medio del Mar Caribe que exhibe un entorno paradisiaco, simplemente alucinante. El lugar está rodeado por una barrera de coral en la que habitan miles de organismos multicolores con las formas más diversas. En los azules más profundos yacen numerosos barcos que embistieron contra los arrecifes y encallaron; la naturaleza se ha ocupado de ellos invadiéndolos por fauna marina.

Los parajes dentro de la isla eran igual de espectaculares, las iguanas tomaban los cálidos rayos de sol y observaban su entorno desde lo alto de las palmeras. Se escuchaban los cantos de las aves que cruzaban el cielo, mientras que los cocodrilos recorrían los manglares o posaban indolentes en la suave arena de la playa.

La noche se teñía más serena y, en medio de la oscuridad, dos biólogos, un veterinario y yo subimos a una lancha para internarnos en los laberínticos caminos del pantano. Este sería el escenario de una de las noches más breves de mi vida, entre la densa maleza, el fulgor de las estrellas en las aguas someras y el canto de un enjambre de insectos, amortiguado sólo por el revoloteo de los cocodrilos al batirse contra el agua al ser capturados.

Pierre iba al frente, de pie en la proa con la luz de su lámpara escrutando cuidadosamente las aguas. Hasta que de pronto, dos pequeñas canicas centellaron a lo lejos. Aunque los cocodrilos estaban casi sumergidos, sus ojos delataban su presencia. Con sumo sigilo nos dirigíamos hacia ellos y, cuando alcanzábamos una distancia prudente, Pierre les lanzaba una cuerda. Al ser atrapados, estos reptiles dan tan vigorosos giros sobre sí mismos que pueden dislocar los brazos de sus captores. Afortunadamente, tras algo de resistencia, los animales cedían y eran izados cuidadosamente dentro de la lancha.

Ya en la embarcación, cubrimos los ojos de los cocodrilos y amarramos sus patas. No sólo porque podían embestir contra nosotros, sino porque al ponerse nerviosos, estos animales sufren un shock glucémico y mueren inmediatamente. Cabe mencionar, ninguno fue lastimado y, después de varios análisis, todos fueron liberados.

Trapping and handling of a crocodile; a juvenile crocodile, Banco Chinchorro. Photos by the author.

Durante el recorrido también encontramos algunas crías camufladas entre ramas y plantas que flotaban con ellos, con sólo estirar la mano pude tomar uno para admirarlo más de cerca. Al día siguiente ‒tras dormir unas horas‒ nos dirigimos a una parte de la isla con cabañas de pescadores sostenidas con pilotes en medio del mar y, en donde un majestuoso cocodrilo de casi tres metros deambulaba las aguas totalmente cristalinas. Sin más, quedé cautivada y de inmediato entendí las analogías que hicieron las culturas prehispánicas. Después de una increíble lucha entre el animal y tres hombres experimentados, el reptil fue capturado, examinado y subsecuentemente liberado.

Banco Chinchorro y un enorme cocodrilo capturado por biólogos. Fotos de la autora.

Una vez de vuelta en la ciudad, continué con el análisis de los materiales arqueológicos y con ello me enfrenté a grandes complicaciones. Desconocía ciertos huesos, no sabía cuáles eran derechos o izquierdos, ni cómo estaban dispuestas las placas que alguna vez cubrieron sus espaldas. Recurrí a manuales especializados, colecciones osteológicas y consulté con biólogos, pero me faltaban respuestas. El estudio óseo de la fauna silvestre es exiguo. La solución era conseguir un ejemplar muerto y descarnarlo, obtener sus huesos y comprender su anatomía. Claramente, una tarea no muy sencilla.

Así comienza mi segunda historia, yendo a mercados de comida exótica y contactándome con granjas de cocodrilos, lugares sustentables que no diezman las poblaciones. Hasta que un amigo del papá de mi novio Ernesto, dio con un taxidermista en una granja de Chiapas. Un caimán había muerto en una encarnizada pelea con otro oponente más grande. Al día siguiente Ernesto y yo tomamos un vuelo al sur de México, determinados a recuperar los huesos.

Mientras descarnábamos al animal con los cuchillos del taxidermista, el hombre nos narraba la formaba en la que cazaba caimanes en los 70s. Iba con otros dos lagarteros, para rastrear a los reptiles seguían las huellas que dejaban en el suelo o imitaban la vocalización de las crías, pues los adultos acudían inmediatamente al auxilio. En pocas horas cazaban hasta 80 ejemplares, terminando la cacería después de reunir unos 400 caimanes. Usaban escopetas y arpones, pero si los reptiles no eran tan grandes preferían golpearlos en la cabeza para no dañar la piel del cuerpo. De manera muy sugerente, una de las pieles de cocodrilo del Templo Mayor tiene dos fracturas en el cráneo, una producida antes de su muerte y otra que no sanó, posiblemente resultado de la forma en la que murió.

Cazar cocodrilos no es nada sencillo, pero capturarlos vivos es una proeza aún más difícil. Seguramente en la época prehispánica estas tareas eran realizadas por expertos que conocían el entorno, el comportamiento de estas criaturas, tenían los instrumentos adecuados y la osadía para enfrentarlos.

Desollamiento y descarne de un cocodrilo. Fotos de la autora.

Mi última historia transcurre en la Ciudad de México, específicamente en el Mercado de Sonora, famoso por los artículos esotéricos que expende. En sus estrechos pasillos con una embriagadora combinación de aromas a hierbas, inciensos y copal, pueden verse esculturas de santos, lociones y pociones para cumplir las más peculiares peticiones, como los néctares de amor, que son los más populares. En cada puesto cuelgan velas de todos los tamaños y colores, muñecos vudú, cualquier clase de extraños amuletos y restos de animales: pieles de felinos, plumas de águilas, patas y cuernos de cabras y arañas en frascos.

De acuerdo con los brujos, ciertas partes del cocodrilo poseen poderes: con las patas hacen “trabajos especiales” que no quisieron detallar; mientras que los dientes y las placas sirven como protección y para la buena suerte, por lo que varios de ellos forman parte de complejos amuletos, como uno elaborado para mí que contiene una placa dérmica de cocodrilo, piel de serpiente, pelo de ocelote, un pequeño santo, cuarzos y numerosas especies de semillas. Tras agregar un pedazo de papel con mi nombre y fecha de nacimiento, el brujo roció todo con un brebaje y lo guardó en una pequeña bolsa roja, asegurando así, mi buena fortuna.

Seguí recorriendo los pasillos y, pese a que el entorno era espeluznante, me pareció fascinante. En algunas esquinas hay enormes figuras de la Santa Muerte que, aunque repudiada por la iglesia católica, está suntuosamente vestida y adornada, rodeada de flores, velas y regalos que sus devotos han dejado a cambio de peticiones o en agradecimiento a sus demandas.

Pero en este lugar difícilmente se pierde el asombro. Al preguntar por dientes de cocodrilo, los comerciantes a menudo ofrecían gustosos los dientes de otros animales. Hasta que, en una ocasión, al hacer mi recurrente solicitud, el vendedor se introdujo un instante en su tienda y sacó algo oculto a la vista, un enorme bote de plástico abastecido de pequeñas piececillas, tomó un puño y puso algunas en la palma de mi mano. Me horroricé, eran dientes humanos: muelas, incisivos y caninos. Después de tragar saliva y regresarlos amablemente, me retiré con miles de preguntas recorriendo mi cabeza ¿cómo obtuvo tantos? ¿acaso saquea tumbas?

El Mercado de Sonora y un amuleto con una placa dérmica de cocodrilo. Fotos de la autora.

Es cierto que a veces la información trasciende los libros, pero el trabajo de los arqueólogos se parece menos a las aventuras de Indiana Jones y más a las investigaciones de Sherlock Holmes. Perseguimos detalles y evidencias que, como pistas, nos ayudan a armar un rompecabezas para desentrañar el pasado. En la excavación, como en una escena del crimen, los materiales se limpian cuidadosamente sin moverlos, tomamos cuantiosas fotos, hacemos dibujos y describimos la posición y orientación de cada elemento, lo que nos sirve para reconstruir y comprender el acomodo original de los objetos.

Dejamos la cucharilla y nos ponemos la bata para hacer diversos análisis en el laboratorio. En mi caso, fue necesario identificar las especies, estimar la edad y talla; describir las condiciones de salud y los tratamientos que les realizaron a los animales. A la par, se consultó invaluable literatura referente a su simbolismo, uso y aprovechamiento.

En ocasiones la arqueología conduce a caminos inesperados, nos permite traspasar sus fronteras, aprender de otras ciencias y enfrentar experiencias que enriquecen nuestras investigaciones. Involucrarme en la captura de cocodrilos, aprender de los biólogos y de un ex cazador, observar las técnicas del trabajo en piel y haber descarnado un caimán me ayudó a vislumbrar la complejidad que requería la selección, la caza, la modificación y el traslado de estos reptiles desde las zonas tropicales hasta el centro de México, en donde con la precisión que exigía el ritual, fueron acomodados en ofrendas que recreaban al mundo. Nunca obtenemos todas las respuestas, pero buscarlas es una oportunidad para surcar manglares, blandir cuchillos o revelar los insólitos secretos de un hechizo.

Erika Lucero Robles Cortés Mesoamerican archaeologist whose interests focus on zooarchaeology, cremation, religion, and ritual. Researcher of the Templo Mayor Project (2009-2021). Among her latest publications is the book: Los cocodrilos, símbolos de la tierra en las ofrendas del Templo Mayor. https://inah.academia.edu/ErikaRobles

Acknowledgments

I am infinitely grateful to my Archaeology Writing Group: Diego Matadamas, Pamela Jiménez and Israel Elizalde, as well as Ernesto Rojas, Matt Fabricant, Maria Dueñas, Marsela Rojas, and Nina Rabkina, whose valuable comments improved and enriched this text. When I told Leonardo López Luján that I would analyze the crocodiles from the Templo Mayor offerings, he replied “If you are going to study these animals, you have to see them alive up close”, his advice was invaluable. I would also like to thank Professor David Carrasco and editor June Carolyn Erlick for allowing me to collaborate with ReVista.

Erika Lucero Robles Cortés es arqueóloga mesoamericanista cuyos intereses se centran en la zooarqueología, la cremación, la religión y el ritual. Investigadora del Proyecto Templo Mayor (2009-2021). Entre sus últimas publicaciones está el libro: Los cocodrilos, símbolos de la tierra en las ofrendas del Templo Mayor. https://inah.academia.edu/ErikaRobles

Agradecimientos

Agradezco infinitamente al Grupo de escritura de arqueología: Diego Matadamas, Pamela Jiménez e Israel Elizalde, así como a Ernesto Rojas, María Dueñas, Silaí Silva, Gerardo Pedraza y Mónica Robles, cuyos valiosos comentarios mejoraron y enriquecieron este texto. Cuando le dije a Leonardo López Luján que analizaría los cocodrilos de las ofrendas del Templo Mayor, me contestó “si vas a estudiar estos animales, entonces tienes que verlos vivos de cerca”, su consejo fue invaluable. También quiero agradecer al profesor David Carrasco y a la editora June Carolyn Erlick por permitirme colaborar en ReVista.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter – Animals

Editor's LetterANIMALS! From the rainforests of Brazil to the crowded streets of Mexico City, animals are integral to life in Latin America and the Caribbean. During the height of the Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns, people throughout the region turned to pets for...

Where the Wild Things Aren’t Species Loss and Capitalisms in Latin America Since 1800

Five mass extinction events and several smaller crises have taken place throughout the 600 million years that complex life has existed on earth.

A Review of Memory Art in the Contemporary World: Confronting Violence in the Global South by Andreas Huyssen

I live in a country where the past is part of the present. Not only because films such as “Argentina 1985,” now nominated for an Oscar for best foreign film, recall the trial of the military juntas…