Transoceanic Traveling Trash

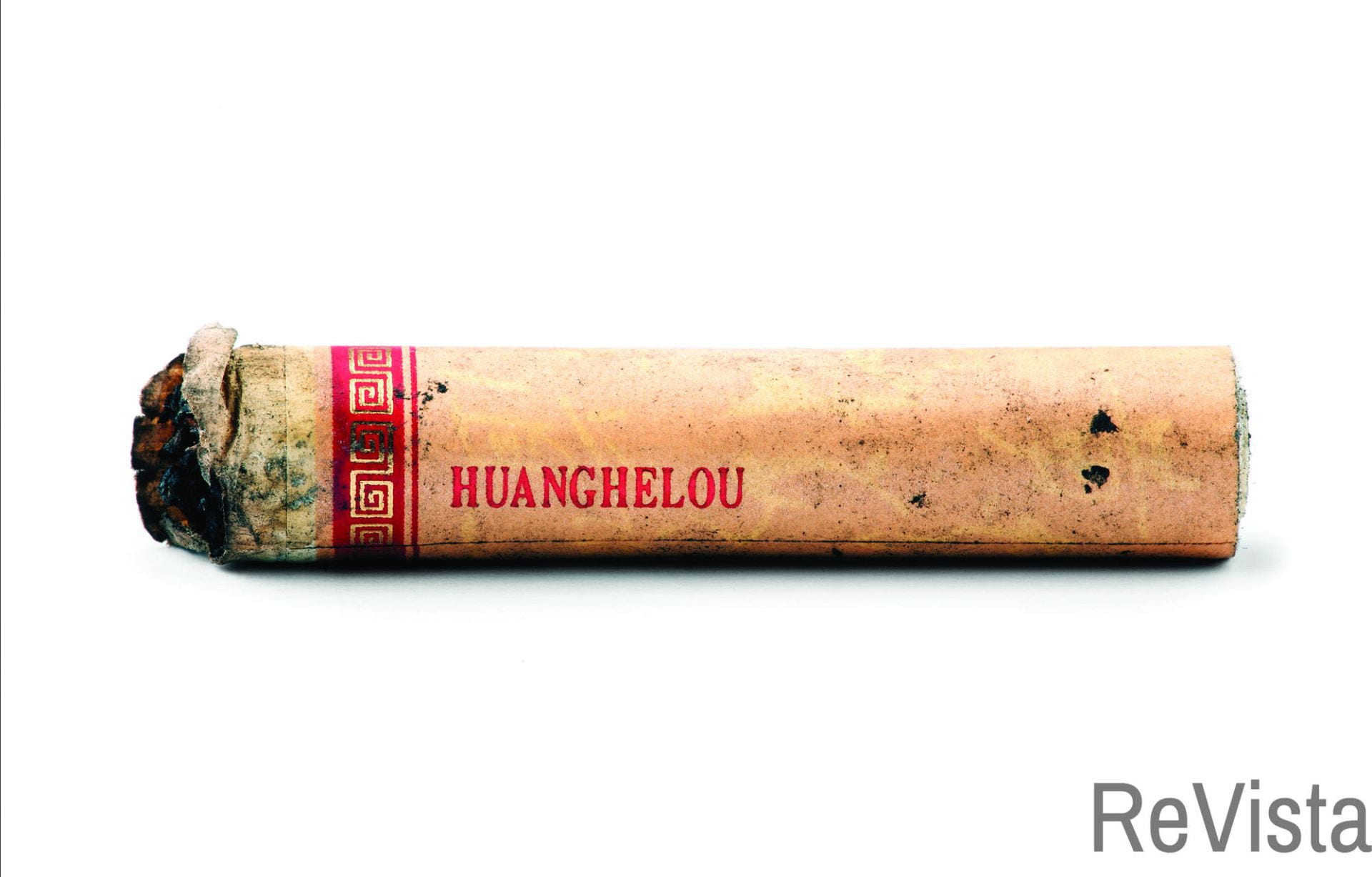

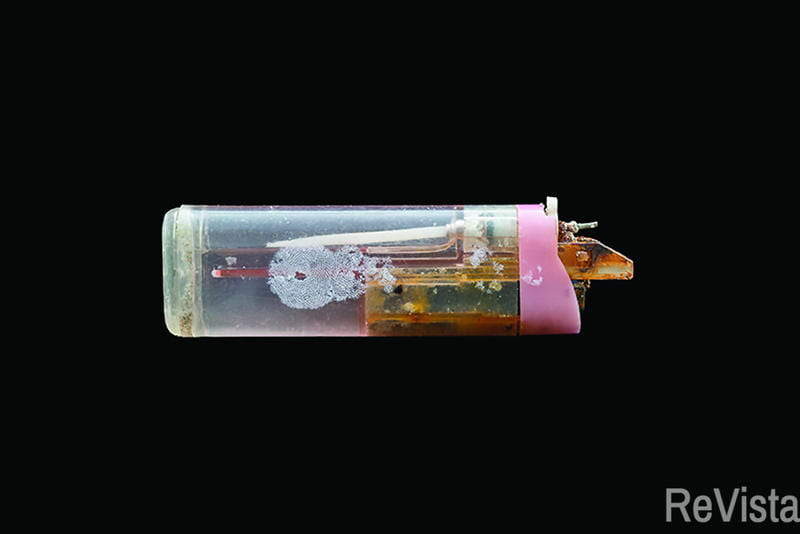

Objects with Chinese characters float up on beaches in Mexico and Peruvian bottle caps land in distant Australian sands. Since 2014, the Mexican art-based research group TRES has been devoted to collecting and investigating marine debris in its Ubiquitous Trash Project. Much of the oceanic realm still remains a mysterious abyss on which hundreds of millions of objects and various lifeforms hitch rides and travel from one location to another—including from Asia to Latin America and back again. Trash is one of these privileged objects that can still move freely in the vast sea if it has the appropriate weight which will determine the direction of movement, utilizing currents or wind. “Trash moves, all the time,” writes Maite Zubiaurre in her article on garbage for the 2015 winter issue of ReVista. Zubiaurre was referring to trash on land. We wish to expand her statement by concentrating on the arguably vaster and less controlled regions of national and international waters.

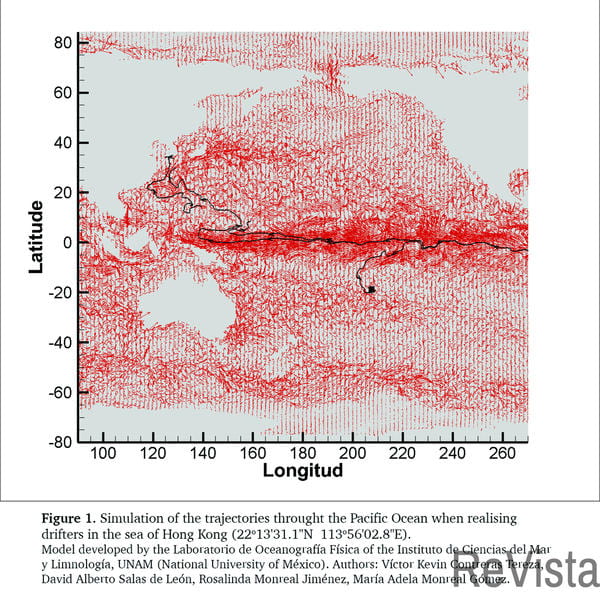

Moved by ocean currents and winds, marine debris composed mostly of plastic can travel enormous distances. One famous example involved a cargo ship that lost 28,800 colorful plastic bathtub toys (notorious for the rubber duckies, that render them very identifiable) en route from Korea to Washington. The Ocean Conservancy Report of 2010 asserts that sixteen years later, many of these items had drifted as much as 34,000 miles, enough to circle the planet almost one-and-a-half times. Not only does plastic travel far, but, as Shakespeare said of truth, it lives long after; beyond our lives. Plastic will linger on earth long after human beings have disappeared, and probably will be able to visit more corners of the globe than any of us. Eight of the top ten countries that filled the oceans with plastic in 2010 are Asian: China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Malaysia, and Bangladesh, according to an article published in the February 13, 2015 Los Angeles Times. The trend continues today. What part of this ends washed up on Latin American beaches? Exact data are incomplete and difficult to obtain. Studies on these movements are almost nonexistent, particularly in the global south, because of lack of resources. The graphic simulation (Fig.1) created by the Physical Oceanography Laboratory in UNAM, Mexico City, in collaboration with the Ubiquitous Trash Project, shows that a piece of plastic on the Island of Lantau, Hong Kong, can end up in the coasts of Chile and with patience in the Atlantic Ocean via the circumpolar current of the Antarctic.

Many citizen based initiatives around the world have committed their time to tracking marine debris. During the last 12 years, the Australian Marine Debris Initiative and the community organisations and individuals involved in the collection and provision of data, detected 143 items from Latin America. Water, milk, detergent and shampoo bottles; an even higher sum of bottle caps; whole chicken packages; a plastic crate; car wash and solvent containers from countries such as Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, Cuba, Mexico, Panama, Peru and Uruguay, washed up on the Eastern seaboard and particularly on the northern shores of Australia. Although some items come from shipping, some of these objects have traveled via ocean currents many miles and countless years.

This is equally true for certain marine organisms, in particular some species of bryozoans, a strange and fascinating tiny (typically about 0.5 millimeters) hermaphroditic aquatic invertebrate that happens to thrive on plastic. Sometimes referred to as moss animals, bryozoans proliferate on ocean plastic fragments, which become vessels that can carry them to other continents. After the 2011 Japanese tsunami, an astonishing transoceanic biological migration was set into motion. An article published in Science Magazine in February 2018 documented the 289 living invertebrate and fish species from Japan that arrived during a five-year period in the central and eastern Pacific Ocean (on coastlines from Midway Atoll to Hawai‘i Island, and from south central Alaska to central California). Millions of objects, from small plastic fragments to whole fishing vessels, served as transportation for these critters. Certainly if the study was continued southward, many more items would have been found in Latin American terrain. This information inevitably leads us to question the prejudices and knowledge we have about the relationship between plastic and life, mobility and travel.

We at TRES investigate the traces and stories that these objects and organisms have to tell. For this art team, trash embodies, among other amazing qualities, a hidden code for understanding post-capitalist distribution and consumption patterns in the world, as well as a supplementary alternative: that of free trajectories on ocean currents and the mobility this provides for diverse objects and species. In an interdisciplinary effort, TRES has collaborated with specialists in biology, sociology and archeology, among others, to map out the possibilities of this paradoxical material we named plastic, so present and useful in our daily lives, but that simultaneously produces much disdain.

Our obsession with traveling trash began in Hong Kong. Some beaches of Lantau Island resemble a post-apocalyptic landscape that took our breath away; a short distance from the impact made by the 19th-century painting The Raft of the Medusa (Le Radeau de la Méduse) by Théodore Géricault. Not because “the evil that men do lives after them,” citing Shakespeare once again, but because the beach became the setting for endless entanglements of correlated information, amalgamations and proof that we are all connected: Asia and Latin America, humans and non-humans. What we do in China affects Latin America, what is done in Hong Kong marks Australia, Finland, Russia and Mexico—thus the name Ubiquitous Trash.

Trash has the capability of voyaging through water at local and global scales. It has no clear frontier. Trash from anywhere can be found everywhere. The beach, in its very nature dissolves boundaries—anything can wash up, from anywhere—and, what does wash up tells us a great deal about not only what people leave behind, but also who and how we are: a collective message in a bottle. Once upon a time the oceans separated us from faraway lands; now they seem to bridge us together.

Fall 2018, Volume XVIII, Number 1

TRES (Ilana Boltvinik + Rodrigo Viñas, Mexico City) is an art research collective founded in 2009 that has focused on exploring the implications of public space and garbage through artistic practices that concentrate on the methodological intertwining and dialogue with science, anthropology, and archaeology, among other disciplines. Of particular interest has been the inquiry on the subject of garbage as a physical and conceptual residue that entails political and material implications. They are the 2016 recipients of the Robert Gardner Fellowship for Photography at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard with which they are currently investigating Australian beaches.

Related Articles

Youth in Postwar Guatemala: Education and Civic Identity in Transition

What happens when young people must simultaneously grapple with an uncertain future burdened with the legacy of conflict, violence, and impunity? Michelle Bellino provides some answers to a question that echoes throughout many conflict-affected areas, Guatemala in…

Social Policy Expansion in Latin America

The welfare state emerged in middle-income countries in Latin America during the first half of the 20th century when health care services and pensions were granted to workers with formal sector jobs…

The Migrant Photography of Haruo Ohara

Japanese began migrating to Brazil 110 years ago, becoming probably the most prosperous minority group in Latin America and certainly the largest Nikkei community in the globe. In 2008,