Universal Health Care

Closing the Equity Gap

Harvard alumna Dominique Elie ‘06 went to Brazil in summer 2003 with an internship grant from the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies. before her trip, she took a photography course through Harvard’s visual and environmental Studies program. her photo essay reflects the diversity of people and places she encountered in Rio de Janeiro.

Brazilian babies are getting more of a chance to grow up these days. Older folk are living longer. Between 1998 and 2004, life expectancy for newborns was extended 3.7 years in Brazil. Men and women over 50 years old experienced a four percent drop in mortality rate from 1998 to 2003.

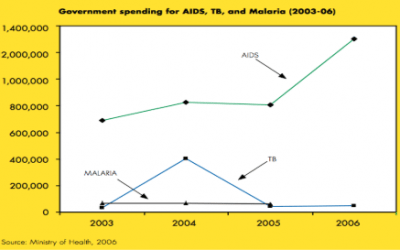

Moreover, since the year 2000, there has been a marked increase in the amount of government spending on health care, particularly at the federal level. It’s no small change either, and also involves greater emphasis on preventive care. The federal budget for health care in Brazil has more than doubled in six years, from about US$10.7 billion in 2000 to a projected US$22.4 billion for 2007. At the state and municipal levels, the increase over this period is estimated at 60 percent, reaching US$37.4 billion in 2007.

These figures come at a time when many governments around the world are cutting back on health care spending. So what’s going on in Brazil?

In 1988, the Brazilian government signed into law a new Federal Constitution. This historic milestone marked the end of a long period of dictatorship in Brazil and put new social policies in place. These policies included the creation of the Sistema Único de Saúde (Unified Health System) or SUS. Article 196 of the Constitution redefined the concept of health care in broad terms as a citizen’s right and as the state’s responsibility. The Constitution also defined the means of financing Social Security, including health care.

Set within the larger context of re-democratization, the health-related measures in the new constitution came about through the efforts of health professionals and civil servants to pursue reforms that would democratize health care in Brazil. Two years before the enactment of the Constitution, the fundamental principles of the SUS were set forth at the 8th National Health Conference, a significant step toward the democratization of health care.

The SUS can be characterized as universal, comprehensive, decentralized and having a high level of community involvement. It is universal in including all citizens regardless of their status within or outside of the formal labor market. It is comprehensive in that it aims to provide care for all health needs from the simplest to the most complex. It isdecentralized in that it stimulates and ensures the political and financial involvement of all three levels of government—federal, state, and municipal. Community involvement is secured through municipal, state and national councils, through regular national health conferences (12 up to the writing of this article) and other forms of representation.

The SUS has achieved much of its success to date by thinking in terms of preventive and primary family care. The strategy for family primary care is to create health care teams dedicated to geographic regions with an average of 2,500 residents. These teams are generally composed of a doctor, a nurse, two nurses’ aides, and five or six health officials. Family care teams are present in 5,000 of the 6,600 cities in the country, providing coverage to 44.4 percent of Brazil’s population and making it possible to implement health policies more effectively. The scope and volume of the services provided is impressive (see table).

In moving to its universal approach to public health care services, Brazil transitioned from a completely centralized system to a decentralized one that includes state and city governments. Prior to the SUS, health care focused primarily on hospitals and specialty clinics and was completely dissociated from preventive care.

Before the new unified system came into being, the National Immunization Program was the only universal health program in Brazil. It operated through health clinics usually administered by the state governments. Municipal clinics only existed in the richest locations. Vaccination coverage, under this system, remained limited.

Over the past 15 years, decentralization has taken root. A 1990 federal law (8080) spelled out the role of each of Brazil’s three levels of government, regulating funding sources to finance an ambitious universal health care system.

One of the fundamental characteristics of the SUS is the agreed-upon and obligatory transfer of federal resources to the state and municipal levels without partisan bias, which, from the legal point of view at least, ensures the process of decentralization.

In the fifteen years since the SUS was formed, health indicators demonstrate important advances in public health care in Brazil. The infant mortality rate declined 20 percent between 2000 and 2004, a significant statistic because it deals primarily with the reduction of deaths in children younger than 28 days old. After the introduction of annual vaccination campaigns, the diseases covered by basic immunization programs have appeared infrequently: polio was eliminated years ago and measles, diphtheria and whooping cough occur only in isolated cases. Health care—including preventative medicine—has become accessible to almost half of Brazil’s population.

CHALLENGES FOR SUS

Despite advances in the standard of care and the implementation of health services since the creation of the SUS, great challenges must be overcome before we can say that there is a satisfactory level of health or a model health care system in place for Brazilians. A brief analysis of the current situation can be carried out by looking at how constitutional principles regarding health and the guidelines and organization of the SUS are being implemented.

As for universalization, we should bear in mind that there is still a segmented system in place which consists of the SUS and a supplemental system of private individual and collective health plans which involve direct payment by the patient and are characterized by expenses for prescription drugs and dental care. The coverage provided by the SUS needs to be extended to include prescriptions and dental coverage, which account for close to 25 percent of the country’s health care costs. Similarly, Brazil faces innumerable challenges in confronting the inequalities that exist across its different regions and socioeconomic classes and in providing access to and allocating resources. Health administrators have a great deal of ground to cover in their efforts to achieve the goal of equitable and universal coverage.

In considering the constitutional guidelines for the SUS, various additional hurdles come to mind:

- The decentralization of the SUS was implemented effectively, principally in the transfer of resources and responsibilities to municipal councils. Decentralization, however, runs contrary to the Brazilian government’s federal principles, which have implications for determining the role state governments play in the management of the SUS and how to coordinate the responsibilities and actions of the three levels of government.

- The integration of health care has been viewed as one of the most difficult problems to address as it requires numerous changes, both conceptual and cultural. It should be analyzed along two fronts: horizontally, looking at how the patient is seen in light of his or her “biopsychosocial” (biological, psychological and social) aspects, and vertically, in which we seek a definition of technological hierarchy that is rational and based on scientific evidence in order to ensure comprehensive, efficient, and effective care.

- Despite the accumulated experience of the National Council of Health and several state and municipal councils, the role of community involvement stills needs to be more clearly defined in terms of its capabilities and its scope. Community participants appear to hope for conditions that would raise the level of politicization in academic discussions, which in turn could serve as the fuel to propel the SUS on the road of progress.

In conclusion, it is appropriate to address the problematic context of financing the SUS. Even with the constitutional amendment in 2000 that earmarked funds to be spent on health care, national spending has continued at a relatively low level when compared to similarly developing countries. Per capita spending is inferior to that of Chile, Argentina and Colombia. The majority of analyses concerning an increase in financial resources for publicly-funded health care conclude that it is not politically viable to increase funds through tax hikes. Brazil’s taxation rate is already one of the highest on the planet. This, in turn, suggests two possible alternatives: an effective policy of growth and socioeconomic development, and a greater allotment to health care of present and future public funds (including funds from unions, and state and municipal governments).

These two alternatives require taking on complex political and technical challenges. If successful, however, they would drive enormous progress in strengthening and modernizing health care management and service delivery in Brazil. And quality universal health care might well be the greatest social victory for the Brazilian people in their history.

By the Numbers: Public Health in Brazil (SUS)

| US$22.4 billion | Federal health care spending in 2007 (up from US$10.7 billion in 2000) |

| US$37.4 billion | Municipal and state spending in 2007 (up 60 percent from 2000) |

| 3.7 years | Increase in life expectancy for newborns between 1998 and 2004 |

| 4 percent | Drop in mortality rate for men and women over 50 between 1998 and 2003 |

| 12 million | Volume of in-patient stays per year* |

| 151 million | Number of visits to doctor per year* |

| 140 million | Vaccine doses administered per year* |

| 1 billion | Primary care procedures per year* |

| 15,000 | Transplants per year* |

* Assumes a population of 130 million people that is exclusively covered by the SUS.

Spring 2007, Volume VI, Number 3

José Cássio de Moraes is Director of Social Medicine in the Faculty of Medicine at the Santa Casa de São Paulo.

Paulo Carrara de Castro is Assistant Professor of Social Medicine in the Faculty of Medicine at the Santa Casa de São Paulo.

Related Articles

Why Brazil Responded to AIDS and Not Tuberculosis

You are probably familiar by now with the famous “Brazilian AIDS Miracle.” A strong, highly centralized AIDS bureaucracy, the incorporation of a well organized civic movement and strong…

What Brazilian Mothers Believe

One Brazilian mother was embarrassed because her children were thin. She thought family and neighbors would think she could not provide enough food for her children…

Using Dance to Set and Achieve Goals in a Favela

Less than three weeks into my year-long fellowship in Brazil, I wrote in my journal one morning: “The violence is intimidating and saddening… it’s quite debilitating and last night it led to a feeling…