Venezuela’s Student Movement

A Web Feature

When the screen faded to black, ending the 53-year history of RCTV, Venezuela’s oldest and most popular TV network, Venezuelans screamed, banged pots and pans and cried.

“I can’t believe he did it, he really did it,” some said incredulously. President Hugo Chávez ‘s decision not to renew the network’s license activated a student opposition movement that had been largely dormant up until then. In turn, the surge of this movement gave rise to an alternative pro-Chávez student movement.

While other networks had made their peace with the government, toning down their criticism, RCTV had continued assailing Chávez and his policies. Fresh off a strong re-election victory, Chávez decided to gamble some of his political capital to eliminate one of his biggest enemies.

But closing RCTV angered Venezuelans across the political divide. A survey by Datanalisis, a Venezuelan polling firm, showed about 70 percent of Venezuelans opposed the closing.

Like the stunned population, these students were at a loss about what kind of action to take against RCTV’s closure, which the government claimed was owed, in part, to RCTV’s alleged participation in the 2002 coup. The week of the closing, a student asked at a meeting, “Aren’t we going to do anything about RCTV?”

At 5 a.m on May 29, five hours after the screen faded to black, students closed the entrances to the private Andres Bello Catholic University (UCAB) in Caracas, setting off over a week of student-led protests in cities around the country.

“The country felt for the first time that the president had attacked them psychologically,” said Francisco Marquez, a student leader from the Catholic university, known in Spanish as UCAB. A part of Venezuelan life for decades, closing RCTV led many Venezuelans to feel they were losing something dear to their lives and even their sense of being Venezuelan.

Not all agreed. Pro-Chávez students see the opposition student movement indirectly represents U.S. interests. UCAB law student Robert Serra, a member of Chávez’s Presidential Student Commission, created as an answer to the student movement, declared in an interview, “They [the opposition students] respond entirely to opposition interests, which are directed by Washington, and whose aim is to destabilize the revolution,”

In colorful language, Chávez had immediately branded the fresh-faced opposition students as a bunch of “mama’s boys,” tying them to what he called the coupmongering opposition and its U.S-imposed directive to prepare a “soft coup.”

Claims of collaboration between the U.S. government and opposition students appeared to some to be bolstered earlier this year when opposition student leader Yon Goicoechea won the Milton Friedman Prize for Advancing Liberty, a $500,000 prize awarded by the right-leaning libertarian Cato Institute, a Washington think tank. Goicoechea came under fire by government supporters, who nicknamed him, “Medio Mi-Yon,” or “Half a Mill-Yon,” “Mi-Yon” in Spanish meaning “My Yon.”

“Those students have no idea of the damage the Milton Friedman award did among people who supported them,” said Serra. “It created friction among members of the movement.”

Stalin Gonzalez and Fabricio Briceño, two prominent leaders of the opposition student movement, said they would not have accepted the award. Goicoechea has said the money will be used to start a youth leadership training center.

It may irk the government that what’s considered a traditionally leftist constituency, university students, should oppose it in significant numbers. Although Bolivarian student groups now have an active presence at the traditional universities, experts say that the middle-class dominated opposition student movement is still prevalent among the university student population. Chávez hopes to change that situation, both by reinforcing pro-Chávez student groups, focusing on issues students care about, and including more non-middle-class students in the university system.

Education plays a central role in Chávez’s socialist-inspired revolution, which has created a university equivalency program, started new universities and has grand plans to build many more. Tens of thousands of poor Venezuelans have benefited.

So as Chávez dismissed the student movement, selling the RCTV closing to the doubters among his base, the movement was winning them over.

“It had nothing to do with politics, it was more pure and sincere,” said Francisco Brandt, an opposition student leader at Caracas’ elite Metropolitan University. “Thousands of students hitting the streets, people see that and it moves them.”

Starting with freedom of expression as its rallying cry, the opposition student movement soon broadened its message to include a wide range of rights, hoping to overcome the country’s polarization. The students refused to attack Chávez personally to avoid alienating his supporters. They denounced threats to basic democratic freedoms but also criticized what they saw as the government’s ineffective social policies. They recognized the need for social programs, demanded by the poor and championed by Chávez, and kept the discredited opposition at arm’s length.

“The discourse tries overcoming polarization and extreme positions, it’s very pluralist and inclusive,” said Maria Teresa Urreiztieta, a professor at the Simon Bolivar University. “It’s not tied up with the opposition, the coup, the strike. It establishes a distinctive brand. ‘We’re not here to overthrow Chávez.’”

Except for Chávez himself, who rode to power in 1998 on a wave of citizen distrust of corrupt politics, political actors still lack much credibility among Venezuelans. (As a lieutenant colonel, Chávez conducted a failed 1992 coup, which brought him to national attention.) Lacking a credible opposition, students with no seeming interest in elected office and a discourse that transcended politics as usual to focus on issues won the trust of many Venezuelans.

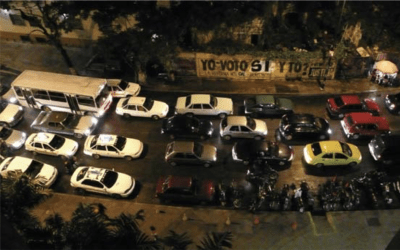

As the country prepared for a referendum on reforming the Constitution, Venezuela’s opposition student movement helped channel widespread discontent not just about RCTV but about government inefficiency and corruption. With many Venezuelans worried about what Chávez’s proposed constitutional reforms would do to the country, the student movement touched a nerve.

Although the opposition student movement came down to “human rights,” the students’ vision of those rights was often skewed toward a focus on political rights, especially freedom of expression, sometimes leaving out social and economic rights. The middle-class based non-student political opposition has focused on political rights, thus appearing out of touch with the lives of ordinary Venezuelans.

Chávez’s so-called Bolivarian Revolution, named after 19th century South American liberator Simon Bolivar, has directed billions in oil revenue to health, education and food programs in the country’s slums. While the results of those programs are hotly debated in Venezuela, Chávez has established himself as the champion of social and economic rights.

“Our focus has to be resolving problems: inflation, unemployment, access to education, crime,” said Stalin Gonzalez, a prominent opposition student leader last year who, at 27, has jumped into electoral politics to run for mayor of the Libertador municipality, the very one that resisted the student marches. “Democracy and freedom are a petit bourgeois issue.”

Nevertheless, Miguel Caceres, a pro-Chávez student activist at the Central University of Venezuela (UCV), sees the opposition student movement as focusing almost exclusively on political rights. “My fundamental critique is that there are much more important problems among Venezuela’s youth,” he said. “If they used that energy to protest for workers, they’d be an interesting alternative for power.”

Some opposition student leaders have indeed embraced a broader concept of rights, emphasizing political rights as a means to an end.

“Freedom is going to allow you to achieve social rights,” said Marquez, the opposition student leader from the Catholic University.

Chávez’s 33 constitutional reforms sought to scrap presidential term limits, develop a state-centered socialist economy, and establish community councils, dependent on Chávez, as local self-governments that would carry out works projects and oversee public services. Chávez sweetened the deal with a cut in the work-day and social security benefits for taxi drivers, street vendors and other workers in the informal economy, measures that could be implemented through laws.

After the pro-Chávez National Assembly added another 36 reform proposals in late October, Venezuelans had little over a month to make up their minds. Polls showed most Venezuelans rejected the reforms, but voter abstention seemed likely to hand Chávez’s “Yes” option the victory.

Many in the opposition student movement expected to lose the referendum.

“There were various scenarios,” said Manuela Bolivar, an opposition student leader who recently graduated from the UCAB. “The one we least considered was winning.”

When the National Electoral Commision (CNE) delayed the announcement of the results, they fueled speculation, and fears, nationwide. Goicoechea, the face of the student movement, received a call on his cell phone from the DISIP, Venezuela’s intelligence agency, saying they would respond if students hit the streets that night.

“Yes, we are going to go out to defend the Constitution whatever the cost,” Goicoechea told the DISIP officer.

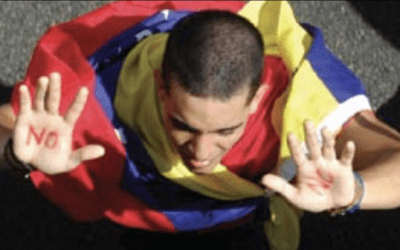

El Nacional, a privately-owned opposition daily, reported that Chávez, who wanted to wait for every vote to be counted, gave in to military pressure to accept his first electoral defeat, an allegation that the Chávez government vehemently denies. The CNE announced around 1 a.m that the “No” option had won both sets of reform proposals by a margin of about 51 percent to 49.

“When the results came, it was a shock,” said Bolivar. “We couldn’t believe we had won.”

Carlos Sierra, the president of the Bolivarian Students Federation, recognizes the movement’s role in the referendum’s results. “People bought into the discourse,” he said. “The new faces, young people, not being seen as part of the old politics. It had an effect.”

To many observers, the opposition student movement made the difference in the referendum.

Since then, lacking the urgency of a constitutional threat, the movement has faded. Some student leaders have entered electoral politics, including González who is running for mayor of the Libertador municipality next month under the banner of opposition party A New Era.

At a party rally in Caracas, Gonzalez’s appearance elicited chants of “U-U-UCV,” referring to Gonzalez’s alma mater. His campaign slogan, “100% Caracas,” is taken from “100% Students,” the ticket Ricardo Sánchez, a party member and Gonzalez friend, ran on in the last UCV student government elections. Sánchez, the current president of UCV’s student government, appeared onstage wearing a “100% Caracas” T-shirt, later taking the microphone to introduce Omar Barboza, the party’s president.

“Ricardo Sanchez is in almost every state raising the arm of an opposition candidate,” said Sierra, who studies communications at the Chávez-created Bolivarian University of Venezuela. “They have a double discourse. They’re fresh faces not allied with political parties, but several are in political parties.”

Serra from the UCAB sees the opposition student movement as dead, largely due to leaders who used the exposure to launch political careers.

“They have let people down,” said Serra. “They have split and demobilized. They are part of the past.”

Chávez himself recently picked twenty-six-year-old Héctor Rodriguez, another member of the Presidential Student Commission, to be his Minister of the Presidency. Pro-government students, committed to the revolution, don’t claim independence, however.

The quick jump into electoral politics, joining new parties seen by many as carryovers from the old guard, threatens the opposition student movement’s precious credibility by making student leaders look opportunistic. If student leaders run for office as soon as they graduate, they risk being seen as preparing themselves for political office rather than simply contributing to change for its own sake.

“They are bewitched by politics,” said Urreiztieta, the college professor.

A victim of its own success, the opposition student movement confronts the question of how to remain a vital social movement, while some of its leaders morph into politicians as soon as they gain recognition.

Gonzalez insists on the opposition student movement’s role as a social movement, but argues that the way to change corrupt political parties is by joining them.

“You can’t change the parties by not being in them,” said González. “We have to begin to believe in politics again.”

José Orozco is a freelance journalist in Caracas, Venezuela. He has published articles in the Christian Science Monitor, The Sunday Times of London, Houston Chronicle, Toronto Globe and Mail and other English-language media. He can be reached at joseorozco78@hotmail.com

Related Articles

Plants Under Stress in the Tropical High Andes: Learning from Venezuela and Beyond

Tropical mountains are privileged places for ecological studies. Going up and down the slopes, like the ones surrounding my home town of Merida, Venezuela, we may simulate changes in temperature. While moving from one slope to the next or moving along seasonal precipitation gradients, we may study plant responses to water availability. These studies have shed light on identifying possible climate change effects on …

A Design Revolution: Caracas on the Margins

We write with a sense of urgency as we hear the deafening sounds of the city. When we read that the price of oil has rocketed to more than $140 a barrel, here in Caracas we are reminded of the impact of oil on the development of our city, first by despotic petro-populist development and later by hyper real petro-dollar development. Caracas continually faces blind building aggregation and arbitrary political decision-making, but …

Forum Venezuela: Moving Students, Student Movements

Harvard’s Forum Venezuela, a student-run organization, seeks to promote awareness of Venezuelan issues and culture, while connecting Venezuelan students living inside the United States both to each other and with their countrymen and women back home. The Forum was founded in the mid-1990s by Kennedy School of Government students who wanted to reach out beyond the confines of the school and to the sizeable but …