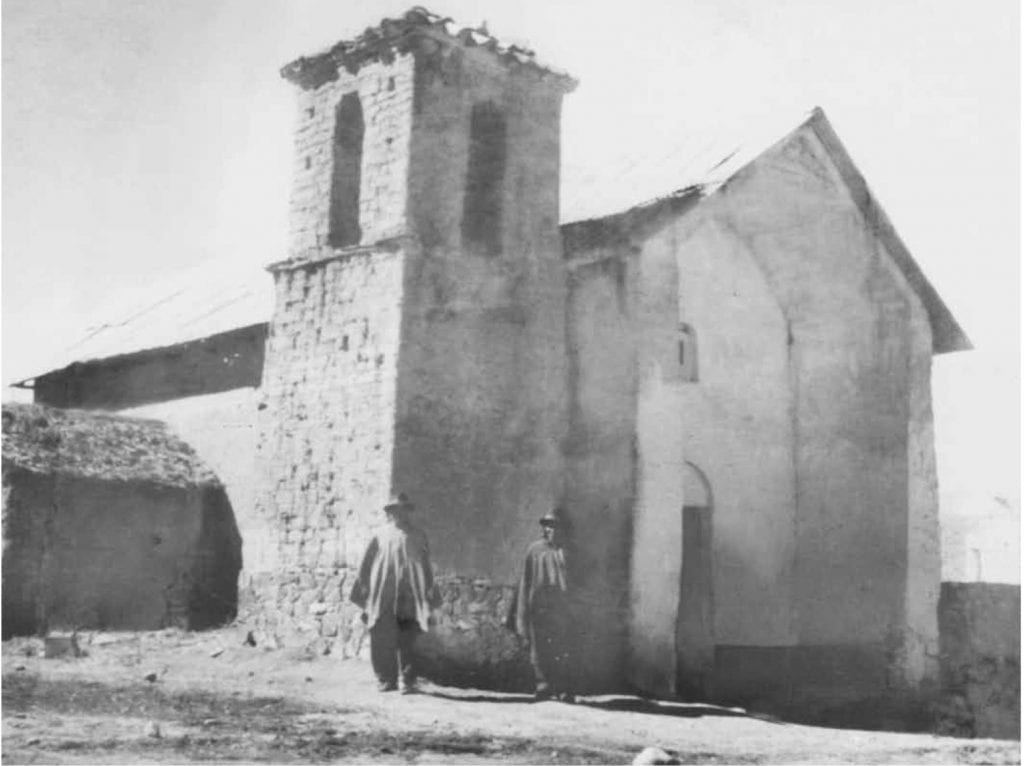

Warisata

A Historical Footnote

This year, on August 2, Bolivia will commemorate the 80th anniversary of the founding of the escuela-ayllu of Warisata, an extraordinary intercultural experiment in indigenous schooling that flourished between 1931 and 1940 on the high plateau (altiplano) in the shadows of the volcanic peak of Illampu. On that day, the usual civic rituals and official remembrances—school pageants, TV documentaries, and editorial page reflections—will mark the school’s founding and burnish its iconic status in the public memory. For some older Bolivians, this commemoration will also signal the passing of the last members of the founding generation of Aymara peasants and white teachers, who carved out an emancipatory Indian school in a hostile social environment, and whose testimonials of struggle and repression serve as the last living link to this past.

Memory and myth aside for the moment, the documentary record accords Warisata a pioneering place—not only in Bolivia, but in Latin America’s history of popular and indigenous school projects. That larger pan-American history of school reform burst into public consciousness in the 1960s, when Brazilian educator Paulo Freire began to popularize his educational philosophy, known as “the pedagogy of the oppressed.” But long before Freire began preaching his program of adult education, a humble rural school, located in an Indian village named Warisata, had been crafted out of intercultural dialogue and hands-on collaboration between a few white educators, who had ventured into the region, and Aymara peasants who put their faith, labor and trust in the school project.

The school, which eventually drew hundreds of students and families from surrounding villages, was planted squarely within the matrix of the traditional kin-based, landed community (or, ayllu). Working along side the school’s teachers and director, Aymara communal work parties (minkas) baked adobe bricks and raised the school building, donated lands in exchange for the education of their children, built an aqueduct to channel Illampu’s glacial lake water to the school complex, and tended the school’s fields, flocks, and orchards that provisioned the school children (including its large boarding population). The school’s intercultural egalitarian ethos (based on traditional norms of reciprocal exchange, or ayni) also governed the school’s administrative and judicial workings. An Aymara parliament of amawt’as (wise elders and counselors) participated in policy making, governance, arbitration, and discipline, and the rustic parliament was also turned into a forum of Aymara oratory, debate, and discussion about broader social issues and grievances that burdened indigenous people.

The prosaic workings of this school surprised many white visitors to the school, because it breached society’s prevailing racial-caste norms that proscribed hard manual labor to white men (particularly men of letters and educators) and, at the same time, presumed Indians incapable of oratory and rational thought—much less of participatory democracy and self-governance. It was not uncommon in the late 1930s for a visiting journalist or politician to recall in utter amazement the dignity and eloquence of Aymara amawt’as speaking before an assembled group of Indians about the issues of the day, or to remark on the extraordinary “enthusiasm” that Indians demonstrated in their concern and participation in matters of education. Equally impressive to foreign educators was the school’s innovative curriculum (blending practical agro-industrial skills with academic work, and often using bilingual methods of instruction). The curriculum, driven by an ideal of practical knowledge tailored to the material needs and cultural values of the Aymara community, was also responsive to the fierce desire of Aymara communities to acquire new forms of instrumental knowledge or cultural capital (access to the dominant Spanish language, alphabetic literacy, bureaucratic, historical, and legal knowledge, etc.) to press their claims against hostile landlords in Bolivian courts of law or government ministries.

The fact that this community-based school was turning into a wellspring of Aymara civic knowledge and activism was, by itself, sufficient to turn it into a target of landlord reprisal and persecution by local political authorities. But it was the scope and intensity of Warisata’s influence—the fact that it eventually irradiated political and institutional influence across a wide swath of territory and attracted multitudes of indigenous “pilgrims” to its festivals and assemblies—that put it on the landlords’ psychic map as a major irritant. Just as the school’s fame was spreading beyond Bolivia to Peru, Mexico, and the United States (which sent streams of visitors to observe this innovative school), Warisata became a source of bitter debate among educators, intellectuals, and politicians at home. Bolivia’s conservative aristocracy accused Warisata’s teachers andamawt’as of preaching racial hatred, walling off the Indian school from national society, and stirring up the restive peasantry across the altiplano. But the school also came under attack from a faction of progressive educators, who denigrated the school’s underlying philosophy of cultural pluralism and instead pushed forward an assimilationist agenda, aimed at converting Aymara (and Quechua) Indians into generic (culturally “mestizo”) campesinos. When the oligarchy suddenly returned to power in 1940, the assimilationists seized this moment to strike. In a matter of months, Bolivian public education was revamped (at least in theoretical terms) as the state’s arm of Indian assimilation. Warisata was invaded and transformed. Bolivia’s unique, decade-long experiment in communal schooling was crushed and publically reviled.

Given its dramatic history, it is hardly surprising that Warisata’s afterlife has been a history of conflictive memories and antagonistic narratives. At worst, the political struggle for memory has devolved into caricatures of the school in its heyday: its critics represented Warisata as a mortal threat to the nation (which was then rescued by the oligarchic elites from imminent race war or revolution by abolishing the escuela-ayllu); while its defenders fashioned Warisata into an Andean socialist utopia, which was just beginning to liberate the Indian from the long nightmare of internal colonialism (before Bolivia’s reactionary elites took the school down and snuffed out the peaceful process of Indian emancipation). The bitter lesson in 1940 was not lost on Warisata’s champions: there could be no emancipation of the Indian without revolutionary change.

After the 1952 National Revolution, Warisata’s currency began to rise in official memory, but the school was unmoored from its indigenous origins and turned into a nationalist symbol, consonant with the project of the National Revolutionary Movement (MNR) to remake Indians into campesinos within a unifying mestizo nation. On this new public stage, the school’s past acquired a new significance. It became an emblem of the government’s heralded Agrarian Reform policy, which was proclaimed to the nation and the world in the peasant town of Ucureña (Cochabamba) on August 2, 1953. From then on, the official history and memory of Warisata were eclipsed by (and conflated with) the post-revolutionary state’s tactical decision to turn that date into a state holiday commemorating the MNRled revolution and its 1953 land reform. The event was part of the state’s new nationalist narrative that fashioned the ideal campesino into the embodiment of rural progress and national unity. All things Indian, including the deep ethnic politics and conflictive history of Warisata, were to be banished (or else, sanitized as national folklore) from political discourse in the post-revolutionary era of cultural nationalism. Meanwhile the state’s 1955 Educational Reform code mapped out a curriculum that would spread schools, but suppress indigenous languages, histories, and identities. Silence and forgetting wove the subtext of the MNR’s newly revamped national holiday heralding the end of the Bolivian latifundio, while projecting a modernizing agrarian narrative devoid of Indians.

Over the next two decades, there were occasional excursions into the past, and Warisata would crop up again in the news or in public commemoration, especially with the passing of another decade. A few stalwarts, men like Elizardo Pérez (co-founder and director) and Carlos Salazar Mostajo (teacher in the late 1930s and later a writer, artist, and journalist), did their best to bring to life, though their own memoirs and stories, the history of sacrifices and hardships, as well as the triumphs and achievements, that went into the making of the escuela-ayllu. On the negative side, Warisata continued to be the target of pedagogical criticism of its alleged failings.

Warisata’s resurgence as a meaningful landmark in Bolivian public history came only in the 1970s and 1980s, when a new generation of Aymara and Quechua activists, scholars and intellectuals began to reengage the past and, through their own scholarly writing and teaching, began to unearth the hidden narratives of indigenous-centered history that had been so long buried under official memory. As indigenous cultural values became the driving force of rural and urban mobilizations across the altiplano, and as trade union leaders and university youth began to attack the structural racism and inequality that had marginalized most native people, a few Aymara students began to rediscover and rescue an alternative collective past. Warisata’s activation as a powerful indigenous symbol, and its growing mystique in the public memory, were part of this larger political and cultural shift going on in Bolivia at the time, as its indigenous majority (including, by the 1990s, tropical lowland peoples) staged protest actions and began pushing cultural and economic agendas that included a fundamental challenge to Bolivia’s system of public education. In the search for cultural revitalization and empowerment within a reimagined multicultural nation, Aymara-Quechua leaders looked to the past for inspiration and guidance. They found it, at least in part, in the buried history of Aymara communities’ struggles for the right to communal lands and village primary schools that took place in the early part of the 20th century, when most peones were still forbidden to learn how to read and write. In the late 1980s and early 1990s local scholars (including Roberto Choque Canqui, Carlos Mamani, and a collective of young historians [popularly known as THOA]) fanned out across the countryside to collect oral testimonies and dig into provincial archives. They harvested rich material showing that, in many regions, rural Indian communities had a deep, semi-clandestine history of organizing and subsidizing rural literacy schools in the void of absent state support and in the context of local colonial-styled violence. These scholars also pieced together narratives that re-situated the origins of Warisata in this larger history of Aymara communities and their emancipatory struggles for lands, schools, and justice under successive oligarchic regimes. This new research revealed, for example, the foundational role that Avelino Siñani, an Aymara literacy teacher, had played in the mobilization of communal peasant support for Warisata in 1931, and in the public defense of the school’s integrity before hostile state authorities in 1941, just hours before he died.

Within this shifting political and intellectual climate, then, Warisata became a wellspring of collective memory and inspiration for many indigenous scholars, teachers, and activists in search of decolonizing agendas for Bolivian school reform and other areas of social life. Long forgotten or discredited as a failed “utopian” experiment in Indian schooling, in the mid-1990s Warisata finally found a place of honor in the nation’s evolving collective memory, at the very moment Bolivia began reinventing itself as a plurilingual multiethnic nation. But, in September 2003, Warisata became the scene of military violence against striking students and peasants. That shocking turn of events—the unprecedented bloody clash on the school’s sacred ground—set off a series of political events that eventually forced President Gonzalo Sánchez de Losada into exile the following month.

In Bolivia’s current political climate, there is an understandable sense of urgency to plumb the past for knowledge and inspiration in the ongoing search for a genuinely pluralist national culture and educational curriculum—one capable of nourishing Bolivia’s rich heritage of ethnic and ecological diversity. Indeed, Luz Jimenez Quispe’s article in ReVista charts the contours of a “cultural revolution” unfolding in Bolivia today, which is centered on the education reforms (aptly named after the co-founders of the Warisata escuela-ayllu), which were ratified by the congress in December, 2010. This new education reform law is driven by the principles of cultural and epistemological pluralism and by a decentralized and participatory mode of organization. Given the state’s chronic institutional weakness and historic tendency to hype educational reform as the panacea of all things ill, only time will tell how this effort plays out. There is no denying, however, that the 2010 Education Reform represents the symbolic relocation of indigenous peoples at the very core of Bolivian cultural politics and nationality. Collective memories of Warisata, on its 80th anniversary, surely will have deep resonance for many of today’s indigenous activists and educators, in search of a usable past.

Brooke Larson, Professor of History at Stony Brook University, was the Santo Domingo Visiting Scholar at DRCLAS, in 2011. Author and co-editor of several books, she is currently writing a book on Aymara social movements and the politics of Indian education in early-to-mid 20th century Bolivia.

Related Articles

A Review of Default: The Landmark Court Battle over Argentina’s $100 Billion Debt Restructuring

In February 2019, I found myself serving as the special attorney general for the then newly recognized interim government of Venezuela, tasked with addressing more than 50 claims before the U.S. courts stemming from the $140 billion debt inherited from Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro.

A Review of Until I Find You: Disappeared Children and Coercive Adoptions in Guatemala

A student in my “Introduction to Cultural Anthropology” course at the University of Delaware approached me several weeks ago, after hearing about my long-term research in Guatemalan communities, to tell me that they were born there, in Guatemala.

A Review of San Fernando: Última Parada, Viaje al crimen autorizado en Tamaulipas

One of Mexico’s best investigative journalists, Marcela Turati, takes readers to terrorized and traumatized San Fernando, a town known for dozens of mass graves, and exposes the depths of criminal brutality and official corruption that hid the bodies and the truth for years.