Water Access

An Inalienable Human Right and Critical Development Goal

A child collects water from a bladder in a camp near the slum of Cité de Dieu, in Port-au-Prince. Photo by © UNICEF/NYHQ2011-0012/Marco Dormino

Take a moment to imagine your day without water. No morning shower, no coffee, no glasses of water throughout the day, no flushable toilet, no washing your hands. Beyond being an unpleasant day, without water we as a human race would simply perish. Not only are we as physical beings made up largely of water, we depend on it to remain hydrated, to clean and purify, to transport and to sustain the hydrological cycle that is the lifeblood of our ecosystem.

Now let’s think about inalienable rights. The trilogy most eloquently stated in the Declaration of Independence encompasses life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. To sustain the first, air, water and nutrition are the critical underlying triad.

Using an elementary logic, one can then say that within the inalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness is the core human right to water (along with air and nutrition). Without these elements, life becomes a luxury, a lofty aspiration rather than a basic right.

The United Nations organization plays an important role in water policymaking.

Let’s start with July 2010 United Nations Resolution 64/292, which formally recognized the human right to water and sanitation.

This specific resolution formally labeled water as a human right. In short, this means that 193 (member) nations agreed that all humans have the right to water and committed themselves to ensuring that their constituents/citizens would have access to water. We will get into what “access” means later.

With 193 member states and arguably the largest forum for global leadership, the United Nations is best placed to guide standard setting and policy development, as well as to promote and monitor the application of such policies toward assuring the human right to water.

The effort to secure universal access to clean water and sanitation started about 20 years before the 2010 UN resolution, with the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) helping shape the debates that ultimately highlighted the need for clearer development targets. The debates evoked resounding criticism over reductions in Official Development Assistance, along with reciprocal skepticism on the clarity of targets and the monitoring of their achievement.

Then-Secretary-General Kofi Annan received the concerns with sincerity and revisited the 1945 Charter which established the United Nations. Annan held the original organizational vision against the dawning of the new millennium and the rapid evolution we call globalization. And rather than simply defend the original charter and try to mold the world challenges to match it, he initiated what would become a revolutionary report entitled We the Peoples: The Role of the United Nations in the 21st Century, which would become the precursor to the Millennium Declaration—helping to answer many pressing questions and concerns. Here are a few quotes from this report:

The most serious immediate challenge is the fact that more than 1 billion people lack access to safe drinking water, while half of humanity lacks adequate sanitation. In many developing countries, rivers downstream from large cities are little cleaner than open sewers.

Unsafe water and poor sanitation cause an estimated 80 per cent of all diseases in the developing world. The annual death toll exceeds 5 million, 10 times the number killed in wars, on average, each year.

No single measure would do more to reduce disease and save lives in the developing world than bringing safe water and adequate sanitation to all.

Annan saw the September 2000 Millennium Summit as an unparalleled opportunity to reshape the United Nations into a more effective entity of continued and strengthened relevance. The We the Peoples report was presented at the momentous Summit, most notably featuring its core vision for a renewed United Nations as an organization that delivers “real and measurable differences” to people’s lives.

The revolutionary report not only highlighted some of the gravest challenges facing the world at that time, it went further to outline specific goals toward our collective overcoming of pertinent challenges. And on September 8, 2000, following the three-day Millennium Summit, the United Nations adopted the Millennium Declaration from which the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) would evolve soon thereafter.

And one of the greatest values of the MDGs is that they are SMART, that is, Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, Time-bound.

Most people want to know that their goals are attainable and that they can monitor their progress against their plan. This concept is also of great importance to the United Nations—especially given its ambitious goals and initiatives funded largely by member states.

With the MDGs, the UN succeeded in establishing clear, critical targets paired with a simple framework to monitor global progress toward their achievement. The MDGs provided an effective platform on which to build awareness and momentum from credible progress. They help capture synergies across the demographic spectrum—from experts to those of us outside the development and policy-making realm.

And for our purposes, let’s look at MDG 7—“ensure environmental sustainability”—which puts water on the global development map of SMART targets.

MDG Target 7c: By 2015, halve the proportion of people without sustainable access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation.

The seemingly simple step of defining this target was an important first in a series of steps toward its achievement. Through its inclusion in the MDGs, this target is part of a framework that is supported by 193 member states and guided by a variety of leading UN entities such as UNICEF, WHO, UNEP and UNDP (among others). Improved awareness has helped build the platform and the political will to address this life-threatening situation. And a great deal has been achieved—through the guidance and monitoring of UN entities and the commitment of governments and leaders at all levels.

As reported by the WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation, the MDG drinking water target has been achieved. Since 1990, more than two billion people have gained access to improved water, and the proportion of the global population using unimproved sources is estimated at only 11 percent. This represents less than half of the 24 percent estimated for 1990. As a helpful reference point, in 2010, almost 6.1 billion people or 89 percent of the world’s population were using an improved water source. The drinking-water target has thus become one of the first MDG targets to be met.

Not only has the UN pushed the dialogue forward, establishing the MDGs and building capacities to achieve these goals; it has laid the groundwork in terms of defining what “sustainable access” to water means:

Sufficient: According to the World Health Organization (WHO), between 50 and 100 liters of water per person per day are needed to ensure that most basic needs are met and few health

concerns arise.

Safe: Water should be free from micro-organisms, chemical substances and radiological hazards that constitute a threat to a person’s health. Measures of drinking-water safety are usually defined by national and/or local standards for drinking-water quality. The World Health Organization (WHO) Guidelines for drinking-water quality provide a basis for the development of national standards that, if properly implemented, will ensure the safety of drinking water.

Acceptable. Water should be of an acceptable color, odor and taste for each personal or domestic use. All water facilities and services must be culturally appropriate and sensitive to gender,

lifecycle and privacy requirements.

Physically accessible. Water should be found within, or in the immediate vicinity of the household, educational institution, workplace or health institution. According to WHO, the water source

has to be within 1,000 meters of the home, and collection time should not exceed 30 minutes.

Affordable. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) suggests that water costs should not exceed 3 percent of household income.

Let’s recap and bottle the key points mentioned above. The UN helped lead the debates that preceded the dawning of the millennium and the challenges it presented. Through the SMART MDGs, the UN revitalized its developmental focus, giving the world a set of critical development targets, definitions and a framework to measure our collective progress. Specialized UN agencies/entities, such as WHO, UNICEF, UNEP and UNDP, have contributed expert knowledge to build monitoring frameworks and provide tailored toolkits to governments and grassroots organizations to ensure the effectiveness of their individual initiatives.

While helping to build the capacities of governments, NGOs and leaders at all levels to achieve the MDGs and sustain progress, the UN went further with its July 2010 resolution–affirming the commitment of its 193 member nations (and 23 international organizations) to provide sufficient resources to ensure that all citizens have access to safe, clean, affordable and accessible water supplies.

So when we dig to find the roots of water`s formal recognition as a human right we find there intertwined the roots of SMART development: The Millennium Development Goals.

David Daepp is Associate Portfolio Manager with the United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS) where he manages the Anglophone and Lusophone Africa portfolio for the (UNDP-implemented) Global Environment Facility’s Small Grants Programme. He holds an M.A. in International Development Economics from Fordham University and has written previously for ReVista as well as Américas magazine (published by the Organization of American States). He can be contacted at ddaepp@gmail.com.

Related Articles

Grandmothers and Engineers

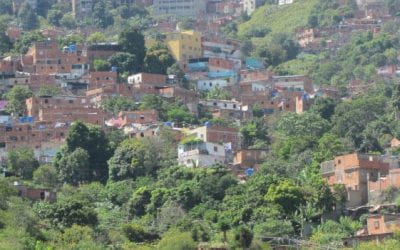

A little known fact about Venezuela is that grandmothers and engineers are at the forefront of the struggle to improve access to water and sanitation in poor neighborhoods. Nancy la Rosa, Rosalba Ruíz, Florencia Gutiérrez, Petra Escalona and Sulay Morales, all in their golden years, are working as spokespeople and organizers of the technical water committees (MTAs, mesas técnicas de agua) …

From Water Wars to Water Scarcity

When Bolivian President Evo Morales arrived at the new Uyuni airport last August and found no water running from the tap, he publicly reprimanded and promptly dismissed his Minister of Water. As it happened, the pipes were merely frozen. The incident underscores the critical—and highly symbolic—role of water in the politics of this landlocked Andean nation. …

First Take: The Struggle for Clean Drinking Water in Latin America

For the last few years I’ve been taking students from the University of Miami to the Galápagos Islands off the coast of Ecuador. We study the environment and the culture. We record the squeaky, hissy conversations of giant land tortoises and the volcanic-black marine iguanas that are found nowhere else. We swim with sea lions and penguins. …