Zamorano and its Neighbors

Lizet and Living Locally

We walked along together, 12-year-old Lizet and I, down the narrow, ragged paths that connected the various houses of El Chaguite to one another. “Let’s call in from here,” Lizet said quietly. “They have dogs that bite.” Or at another house, “Oh, no one talks to this family. People say he killed his wife years ago.” Throughout my time working in El Chaguite, and particularly in those initial days trying to organize a youth group in this unfamiliar, slightly hostile place, Lizet was my tireless helper, a constant source of information on the complex relationships and personalities that filled this small community of 70 families in rural Honduras, a few miles but light years away from my base at the Zamorano campus.

Lizet loved to explain to me the special names they had for the fruit trees in their region, the different customs they had for using plants for medicinal reasons, the superstitions they had about certain animals or weather patterns. And over time, my open ear was all it took for her to begin expressing and articulating her thoughts about her community, her goals, her friends and frustrations. This type of self-awareness and expressiveness, rare in young girls in any culture, was almost unheard of in the girls I met in rural Honduras. And what was especially exciting to me was to see Lizet take an increasingly active leadership role in her community, as if her self-awareness was freeing her to take control of her life in a way that few in her community could. Over the course of our conversations, she was able to “look at herself in the mirror”and her self-awareness enabled her to give back to El Chaguite.

My relationship with Lizet gave unexpected, but powerfully fulfilling, form to the vague economic and ecological ideas that had landed me in Honduras. Inspired by a Harvard undergraduate conservation biology seminar, I had decided that I wanted to work on local level environmental education in Central America after graduation. In addition to my interest in conservation in the tropics, community- level work in a developing country also appealed to me as an opportunity to escape the oasis-like quality of campus life, which had been increasingly weighing on me. I had been rooted in academia all my life – the first 18 years as the daughter of a Stanford professor, and the next four as a Harvard undergraduate – and so I found it hard to shake the sense of living in an isolated community with elevated standards of living. But after researching various alternatives, I found that the best means of pursuing my interest in local level environmental education was through the UNIR rural development project, based on the campus of the Zamorano agricultural college in Honduras. So, despite feeling somewhat leery of living on yet another university campus, I found myself heading for Zamorano.

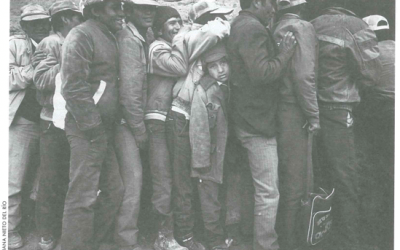

Once there and faced with the realities of life in the communities scattered throughout the steep green mountainsides surrounding Zamorano, everything that had brought me to Honduras was turned upside down. The beauty of these communities-the crops hugging the mountainsides, the splashes of color from tropical flowers and butterflies and clothes hanging out to dry, the red shingled roof tops tucked away behind unexpected turns of the winding dirt road – was breathtaking. Yet this beauty is the product of a degree of remoteness that is intensely disturbing as well. The steep mountainsides that are these people’s homes create unbelievable limitations on their lives, both physically because of inaccessibility to health care and proper nutrition and electricity, and mentally because of inaccessibility to any knowledge about the diversity and richness of the world beyond these mountains. It is impossible to romanticize their remote lives when one sees the poverty that goes hand in hand with the simple beauty – the dilapidated homes, the dirty wandering children, the swarms of flies.

After seeing this reality, I felt inclined to talk to the community members about sanitation rather than biodiversity, and about self-esteem rather than stewardship. It made me question whether my previous enthusiasm for conservation was misplaced. In a country like Honduras, did the truly important work lie in fields like public health and food distribution? At the same time, the contrast between these realities in the communities where I worked and the lovely gardens, unlimited cafeteria food, and computer centers of Zamorano became increasingly uncomfortable to me. I did not begrudge Zamorano any of its accommodations – I savored the e-mail access, hot showers, and excellent library as much as anyone – but it was hard to feel at ease living amidst these contrasts. I found myself struggling harder than ever with how to live responsibly and productively in a world with such fundamental inequities.

These questions became all the more intense in November, when Hurricane Mitch hit Honduras. The river receded in a matter of days, but the currents of pain, loss, destruction, despair, and economic devastation coursed through the area relentlessly. As Mitch’s emergency phase somewhat subsided, I saw more clearly that the problems now attracting such an outpouring of international support were not truly created by the rains. For most Hondurans, life is so thinly based – economically, spiritually, socially, ecologically – that all it takes is several days of heavy rains to sweep away the thin veneer of acceptability and uncover the severe underlying deficiencies of their society.

My relationship with Lizet gave me something to hold on to amidst this confusing, upturned world. Her growth, through the growth of our relationship, showed me that potential for change exists, even in a world fraught with such deep inequities and chaotic tragedy. Mutual inspiration flowed between us; she inspired me with her sincerity, her enthusiasm, and her quiet bravery, while I inspired her with the realization I could provide of the possibilities for change in her life and her community. Through my relationship with her, I discovered an approach to conservation that felt appropriate to the realities of the communities where I worked: conservation centered around the concept of self-awareness. Giving sustainable development work this focus would directly address the region’s short-term, destructive use of natural resources, for I found these unsustainable habits are often the product of a pervasive sense of powerlessness shared by many Hondurans. They feel they can only control the immediate, and thus seek to maximize it, because they have so little faith in their ability to control events down the road. Sadly, most development efforts I encountered only seemed to be furthering this sense of powerlessness. I know that spending one-on-one time with every young person in every rural village in Honduras is an unrealistic proposition, but with a shift in framework and some creativity, perhaps this emphasis on personal awareness could be integrated into larger- scale conservation work.

Equally important, I think, is the need to apply this approach to campus life. I know that Zamorano is a college, not a rural development program, and its responsibilities and goals are diverse and far reaching. Local-level work is perhaps becoming more of an institutional priority, but it needs to become more so to provide a powerful and illuminating example to both Zamorano students and the community. By investing time and care into local level relationships, I believe, self-awareness and inspiration could run both ways, just as it did for Lizet and me. We led one another, each in our own way, through the reality and potentiality of her community, so close to Zamorano and yet so far away.

Fall 1999

Nina Rabin graduated from Harvard College in 1998 in the department of History of Science, an interdisciplinary con- centration in which she focused on the social and scientific dimensions of conflicts over natural resource use in American history. She received a travel grant from the Baker Foundation to spend the year following graduation in Honduras, pursuing her interests in environmental education and sustainable development. She is currently working at the Environmental Law and Policy Center in Chicago, and preparing to enter law school in the fall of 2000.

Related Articles

Poverty or Potential?

Teresa stops me three blocks from Nueva Imperial’s main plaza on a quiet Wednesday morning, eager to chat. She is wearing a light blue sweater and a matching blue headband glowing slightly against her dark black hair.

Infections and Inequalities

I read Paul Farmer’s book while on a short visit to Venezuela, and found that setting, at this historical moment in time, particularly pertinent and highly conducive to the arguments Farmer…

Proclaiming the Jubilee

Carmen Rodríguez heads the Charismatic Movement in a sprawling shantytown parish south of Lima, Peru. She and other lay leaders of the Lurín Diocese have been preparing for the…