Is Costa Rica Different?

Democracy and its Challenges in a Regional Context

Let’s face it—the social and political history of Latin America over the past two centuries has not been a felicitous one. Against this backdrop, Costa Rica stands out as an exception. Already in 1841, a mere two decades after Independence, John Lloyd Stephens’s remarkable chronicle of his travels across the Central American isthmus was sure to mention the visible differences that set Costa Rica apart from its neighbors “The State of Costa Rica,” wrote Stephens, “enjoyed at the time a degree of prosperity unequalled by any in this disjointed confederacy. At a safe distance,…it had escaped the tumults and wars which desolated and devastated the other states.” The observant explorer added that “Throughout (t)his state I felt a sense of personal security, which I did not enjoy in any other” (John Lloyd Stevens, Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatan: Harper & Brothers, 1841; Vol I – Chapter XVII, pp. 359-361).

Electoral campaigns are part of the fabric of everyday life. Photo credit: June Carolyn Erlick

Over the following 150 years the country would chart a peculiar trajectory in Latin America, one generally defined by its commitment to peace, democracy, the Rule of Law, human development and, later, environmental sustainability. Thus, for example, primary education became free and universal in Costa Rica in 1869, before all of Latin America, England and nearly every state in the United States. In 1940, the country introduced a public healthcare and social security system, underpinned by values of solidarity, that largely explains that Costa Ricans today enjoy a higher life expectancy than inhabitants of the United States. While not always pristine in practice, Costa Rica’s adherence to democracy, the Rule of Law, and the peaceful transfer of power was already established in the late 19th century. Its most important deviation from these principles—the short 1948 Civil War—was precisely a conflict over the sanctity of the suffrage that led to the abolition of the army. The latter decision, more than any other, codified a dramatic departure from Latin America’s political history, so often defined by the military’s overbearing presence. To this day, Costa Rica remains the longest uninterrupted democracy in the developing world. Despite being a small, peripheral country, Costa Rica became a symbol of values cherished around the world, and a test case of the proposition that a society’s healthy development depends as much on political commitments sustained over time as on sheer economic wealth.

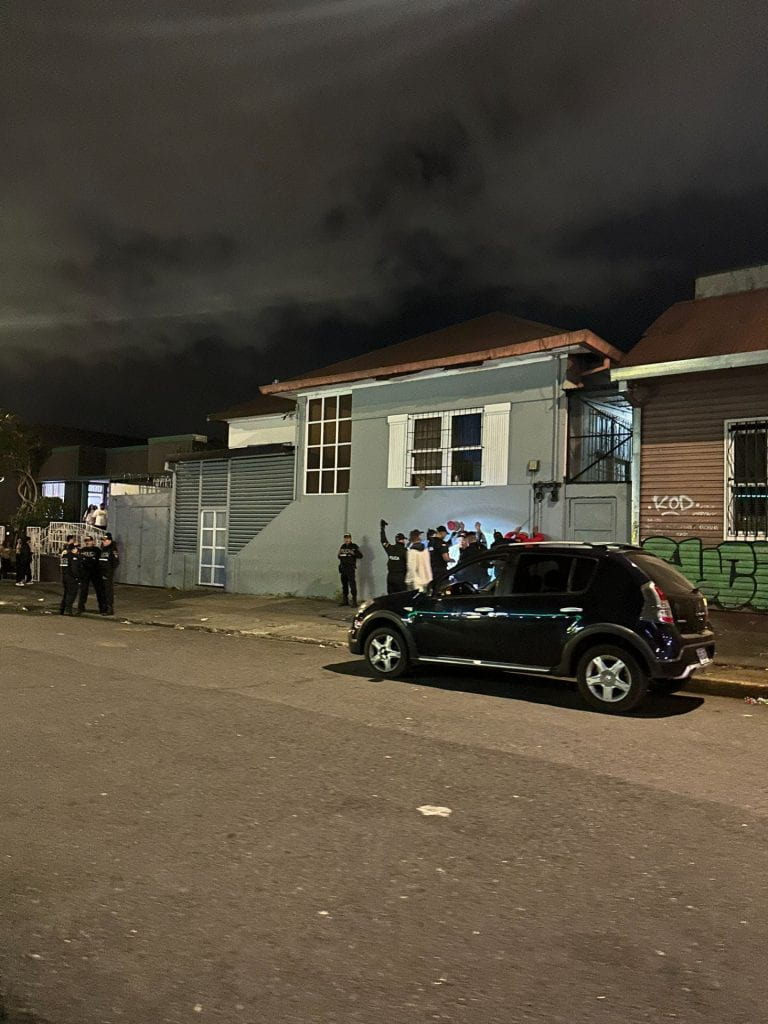

In the club area La Cali in San José, police searched and arrested several people (presumably gang related), 2024. Photo credit: Arianna Fowler. Instagram: @arianna.1108

While by most accounts the country remains a well-performing democracy, some of the defining traits of its remarkable historical journey have been visibly dented over the past three decades. A society long identified with egalitarian values and peaceful coexistence has morphed into a country that now ranks amongst the most unequal in Latin America, with criminal rates that match those of its chronically violent Central American neighbors. Perhaps most shockingly, on the back of glaring governance problems, support for democratic values and institutions has fallen significantly, and more or less continuously, since the 1980s. Partly because of its own mounting problems, and partly as a result of the normalization of democratic rule in the region, Costa Rica’s political and development trajectory has reverted to the Latin American norm.

The 2022 election of President Rodrigo Chaves offered a stark confirmation of this. Chaves, a political outsider, rode to power on an unabashedly anti-establishment, anti-corruption platform, tapping into a deep reservoir of discontent with traditional parties, leaders and institutions. More importantly, his election has marked a departure from the rules of civility and respect for the Rule of Law that have long defined the behavior of government authorities in Costa Rica. As seen in other places where populist leaders gain power, daily and relentless attacks against opposition parties in Congress, media outlets and judges have become a hallmark of Chaves’ rule. In 2023, the country dropped 15 places in the World Press Freedom Index published by the organization Reporters without Borders, and 11 places in the attribute of Representative Government, as measured by International IDEA. The challenges faced by Costa Rica’s democratic system have become more acute. Yet, as of the time of writing, Chaves remains broadly popular with 51% with a favorable opinion of him. Today, the country’s claim to exceptionalism in Latin America appears much weaker than in the past. How did it come to this?

The Unraveling of a So-called Central American Switzerland

The story of how Costa Rica reverted to the Latin American average is a complex one, with long roots and no obvious culprits. Beneath the historical success it was always possible to spot structural weaknesses. Thus, the country’s long-term commitment to investing in human development and creating a network of universal social services was never sustained by a robust fiscal base or, after the 1980s, steadily high rates of economic growth. In the words of economists Leonardo Garnier and Laura Blanco, for several decades Costa Rica managed to be an “almost successful underdeveloped country,” where social progress was anchored more on political decisions and cultural attitudes than economic realities (Leonardo Garnier & Laura Blanco (2010), Costa Rica: Un país subdesarrollado casi exitoso: San Jose, Uruk Editores).

The arrival of the external debt crisis in the early 1980s was a watershed moment. In a remarkable political feat, the country managed to weather a deep economic crisis and the perils posed by the Central American wars, without experiencing a social or democratic collapse. If anything, its democracy emerged from the experience stronger than ever, with a proven capacity to forge broad agreements and enact reforms when it most counted. But the country did not come out of the decade unscathed. The economic model put in place in the wake of the crisis—one much more market friendly and open to the world—soon unleashed a profound transformation of society, in which the considerable opportunities created by the global economy for key sectors coexisted with much deeper social fault-lines.

By the turn of the 21st century, the cracks in the Costa Rican model were becoming visible and worrisome. The country’s very high rates of electoral participation (consistently above 80% over three decades, despite voting not being mandatory in practice) suffered a 10-point drop in the 1998 election, and further decreases since (in 2022 it was 60.6%). This was the prelude to the collapse, four years later, of the two-party system (with the center-left National Liberation Party [PLN] and the center-right Social Christian Unity Party [PUSC] as heirs of the two factions that fought the Civil War) that had ruled the country for 20 years and, in some ways, since 1948. Ever since, the fragmentation of the party system has become a key trait of Costa Rican democracy, as is the case elsewhere in Latin America.

Perhaps more importantly, a country that in previous decades had managed to reduce poverty drastically, enable social mobility and preserve historically good levels of social integration found itself coping with stagnant levels of poverty and a dramatic increase in inequality. Many factors converged to generate these outcomes. They include the bifurcation of the economy into, on the one hand, a small exceptionally dynamic sector linked to the global economy through exports and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), and, on the other hand, a vast majority of economic actors—including a growing informal sector—connected to the domestic economy and saddled with low productivity levels. The retraction of the state from key roles as part of the structural adjustment of the economy in the 1980s and 1990s added to the problem. Crucial levers employed by governments to provide opportunities for social mobility, such as the state’s control of the banking system or the exceptionally active housing policies, were weakened or disappeared altogether in the new economic dispensation. The reduction in public investment and attendance rates in the education system during the 1980s economic downturn and its aftermath had particularly deleterious long-term implications for society. Public investment in education as a proportion of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) dropped nearly 50% between 1980 and 1982. It wouldn’t recover its peak level of 1980 until 2008.

Costa Rica is experiencing stagnant levels of poverty and a dramatic increase in inequality. Photo credit: Arianna Fowler. Instagram: @arianna.1108

Whatever the combination of causal factors may be, by now the results are in. For three decades now, since 1994, the proportion of households below the poverty line has fluctuated around 20%, with no significant changes, except during the Covid-19 pandemic, when it climbed to over 26%. It currently stands at 21.8%. This is despite the priority assigned to the task of reducing poverty by every administration in this period, and levels of economic growth that, while far from spectacular, are not insignificant (2.5% average GDP growth per capita in 1994-2022, according to my calculation based on World Bank data). Almost certainly, the “stickiness” of poverty levels is connected to the much more alarming trends regarding inequality. By 2021, Costa Rica’s Gini coefficient of income inequality (0.49) had become the third highest in Latin America, well above the region’s average (0.46), and a far cry from the national figure in 1990, when it stood at 0.38. Moreover, Costa Rica is the only Latin American country where income inequality levels have increased since the early 2000s.

The convergence of these social challenges and the drug-trafficking maelstrom that has engulfed Central America made it unsurprising that in due course Costa Rica’s historically low levels of criminal violence also came under stress. The murder rate, which stood around four per 100,000 inhabitants for most of the 1980s began an ascent that was first gradual, then severe, and finally irresistible. By 2001 it had become 6.5, which became nearly 11-12 in the 2015-2022 period, and then 17.2 at the end of 2023. It should be mentioned that any rate above 10 is considered serious by the World Health Organization (WHO), and that Costa Rica’s most recent numbers place it above all other Central American countries, except Honduras. The peaceful oasis in a violent isthmus is no more.

The economic situation has led to an increase in the informal economy. Photo credit: Arianna Fowler. Instagram: @arianna.1108

And then there’s corruption. The popular perception that Costa Rica was a reasonably well-governed country, endowed with trustworthy institutions, was eroded, as in Ernest Hemingway’s famous quip about bankruptcy, first gradually and then suddenly. The regular eruption of high-level corruption cases with varying levels of significance since the 1970s gave way to something vastly more serious in 2004. It was then that evidence emerged of the alleged involvement of three former presidents, from both main parties, in schemes to manipulate large public procurement decisions in return for kickbacks. Two of them spent time

in jail. Long legal sagas would eventually lead to one of them being acquitted.

The long-term political impact of the 2004 presidential corruption scandals cannot be overstated. The devastating blow to both traditional parties was merely the most obvious consequence. Much more important was their effect in placing corruption at the heart of public debates, as a kind of one-size-fits-all explanation to all the country’s ills. The proliferation of checks and balances in the name of preventing graft and the quest for incorruptible political leaders able to deliver the country from its crooked path became veritable national obsessions, to the exclusion of almost any other policy consideration. Acute distrust, suspicion and an inclination to veto any reform, just in case, became the dominant notes in the score from which Costa Rican citizens, journalists and political actors have continued to sing until today.

All of this, and many other factors not considered here, contributed to the onset of a vicious political cycle, in which the declining ability of the political system to respond to ever more glaring problems led to the citizens’ chronic anger and political disaffection, increasingly strident political debates, a perpetual quest for new political leaders and parties, ever growing fragmentation of the party system and the constant addition of new and extravagant checks and balances to prevent corruption, the perceived root of all evils. Alas, every one of those reactions has decreased the political system’s ability to act effectively to resolve the problems at the root of popular frustration.

Thus arrived the populist avenger in Costa Rica—President Chaves. As it is easy to see, and whether we like his political style or not, we must admit that the success of a populist leader in Costa Rica is a symptom of deep problems in the workings of democracy. In this, Costa Rica is no different from any other democracy experiencing the turbulences brought about by populism. And, in all likelihood, it will not be different in another way—populist leaders are poorly equipped with solutions to solve complex problems such as Costa Rica’s. Divisive rhetoric and attempts to curtail press freedom and judicial independence will not improve the ability of the country’s political system to deliver the outcomes that society expects. A significant political reform, on the other hand, may help. For at the heart of the unravelling told in this section, lies a story of growing political dysfunction that demands all the attention it can get.

A Dysfunctional Political System

For all its economic trauma, the 1980s were a triumph for Costa Rica’s democracy. Faced with serious simultaneous challenges, the political system proved able to enact the long-term reforms that the country needed to stay afloat in highly troubled waters. The will to forge broad political agreements was such that in 1983 the long-dominant PLN actively helped its main conservative competitors to merge into a unified party (PUSC) that henceforth would simplify consensus building, decision-making and, ultimately, power alternation. As reported by Vanderbilt University political scientist Mitchell Seligson in “Trouble in Paradise: The erosion of system support for Costa Rica, 1978-1999,” (Latin American Research Review, 37, 1, p. 172, 2002), survey data detected very high levels of support for democracy in Costa Rica in the mid-1980s —87 points on a scale of 0-100 in a democratic System Support Index.

Since then, the downward slope has been long and steep. The country’s political system has gradually lost its ability to represent society, process social demands, prevent conflict and forge broad agreements around key reforms in an effective way. In other words, the ability of Costa Rica’s democratic institutions to govern effectively has visibly declined. In his inaugural address, President Chaves decried this notion as a myth propagated by his indecisive predecessors. The evidence suggests otherwise—the problem is real and taking a toll on democracy in Costa Rica.

The country’s political system has gradually lost its ability to represent society and process social demands. International Women’s Day March 2024 Photo credit: Jose Díaz. Instagram: @josediaz2491

Take the evolution of the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators. Using a wealth of sources, since 1996 this global database has published annual measurements of the performance of countries on six key variables of political performance: Voice and Accountability, Political Stability and Absence of Violence/Terrorism, Government Effectiveness, Regulatory Quality, Rule of Law, and Control of Corruption. While Costa Rica’s results continue to be acceptable in the Latin American context, the trends are noteworthy: between 2000 and 2021, five out of the six indicators (with Political Stability as the only exception by little) deteriorated. This places Costa Rica alongside Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Guatemala, Honduras, Haiti, Mexico, Nicaragua and Venezuela, where at least five indicators decreased in the same period.

It is difficult to imagine that this process has no impact on the precipitous fall in support for democracy and satisfaction with it that regional opinion surveys have detected. The peak attained in the mid-1980s and the decades-long jockeying with Uruguay for the top position in the region in all the relevant political indicators has given way over the past few years to results that are no longer in Uruguay’s league and much closer to the Latin American average. Table 1 contains a small sample of survey results that betray a very clear pattern of reversion to the regional norm.

|

Table 1. Perceptions about democracy and trust in key institutions (%)

|

||||

| Item |

Costa Rica 2004 |

Costa Rica 2023 |

Uruguay 2023 |

Latin America 2023 |

| Democracy is preferrable to any other government system | 78 | 56 | 69 | 48 |

| Satisfaction with democracy | 60 | 43 | 59 | 28 |

| Trust in Government | 60 | 37 | 49 | 29 |

| Trust in Congress | 53 | 29 | 48 | 24 |

| Trust in Judiciary | 62 | 45 | 51 | 29 |

| Country is governed by a few powerful groups in their own benefit | 67 (*) | 72 | 62 | 72 |

|

Source: Latinobarometro, see: https://www.latinobarometro.org/latOnline.jsp Notes: (*) 2007. |

||||

Why have the performance of Costa Rica’s political institutions and popular attitudes regarding democracy declined so visibly in the past two decades? It is difficult to know for sure, and even harder to perform such an analysis in a short piece. Yet, it is plausible that some purely political and institutional factors are playing a key role. Let us see.

A first factor is a constitutional architecture and a set of relations between branches of government that appear increasingly out of balance. As per the 1949 Constitution, the formal attributes of Costa Rican presidents (e.g. appointment powers, emergency powers, decree powers, legislative prerogatives, budget initiative) are comparatively weak. A recent study by Amoroso Botelho and Rodrigues Silva places Costa Rica’s presidency as the second weakest in Latin America, only after Guatemala’s. The authors include it as part of a category labelled “potentially marginal” (Joao Carlos Amoroso Botelho & Renato Rodrigues Silva (2021), “Presidential powers in Latin America beyond constitutions”, Iberoamericana – Nordic Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 50 (1): 28).

For a long time, this formal feebleness was compensated through a series of para-constitutional mechanisms that, in practice, enhanced considerably the powers of the Executive to push through its agenda. These mechanisms included, among others, a bi-polar party system that all but guaranteed that the Executive enjoyed a legislative majority or was very close to it; internally disciplined parties in which presidential nominees had a decisive influence in picking legislative slates; budgeting rules that allowed the Executive to allocate funds to local projects sponsored by members of the legislature as a way of securing their support; and procedural rules that turned the budget into a kind of omnibus bill to which all sorts of other government initiatives could be attached and approved through an expedited process. Each and every one of those levers eventually disappeared, in many cases as a result of rulings by the Constitutional Court.

Indeed, the creation of a powerful Constitutional Court in 1989, with much enhanced prerogatives to review executive decisions, and the fragmentation of the two-party system in 2002, are critical junctures that exposed some unpleasant implications of the constitutional design adopted in 1949. These landmark moments greatly enhanced the ability of the legislative and judicial branches to check on the Executive, but left the latter hobbled with its original weak formal powers and a reduced ability to act on its priorities. To simplify considerably a complex story, what gradually emerged was a situation in which the executive branch found it increasingly difficult to execute, the legislative branch found it harder to build the majorities to legislate, and the judicial branch gradually came to replace both, at a considerable cost for its own legitimacy.

The fragmentation of the party system and of legislative representation is, arguably, the key element in this process. The Effective Number of Parties, a measure of fragmentation of the party system, has moved from between 2 and 2.5 in the 1980s and 1990s to practically 5 today. This, in fact, underestimates the degree of political fragmentation. When the parties’ growing internal fractionalization is taken into account the situation gets worse by an order of magnitude. For example, at the end of the 2018-2022 legislature, the Costa Rican Congress included 13 independent deputies (out of a total of 57), namely members that for varying reasons had split from the caucus of the party that enabled their election. Building legislative majorities in Costa Rica has become a painstaking process with very high transactions costs.

Since 1994, no incumbent president in Costa Rica has enjoyed a legislative majority. The well-known challenges that beset presidential regimes when they co-exist with fragmented party systems have become par for the course in the country. In this Costa Rica is hardly alone. This has happened all over Latin America, with few exceptions. One can only speculate here if this is one of the reasons why in 13 out of 18 countries in the region, a majority of the six World Bank governance indicators mentioned above have deteriorated since 2000.

The increasingly fragmented legislative representation is a crucial check on power, but by no means the only one. Costa Rica’s Constitutional Court, which has few parallels in the world in terms of its prerogatives and hyperactivity, has already been mentioned. But one should also add the multiple controls enacted during these years in the country’s zealous quest to prevent and eradicate every single possibility of corruption in the public sector. The key node of these efforts continues to be the constitutional norm that, against the best international practice, enshrines a rigid system of ex-ante controls over every single disbursement in the government, a system managed by yet another powerful agency—the General Comptroller of the Republic. The negative impact of this setup on the speed and complexity of public procurement processes in Costa Rica has been well documented.

In the past couple of decades Costa Rica has become a “vetocracy,” to quote Francis Fukuyama’s much-used concept—a dysfunctional government system in which no entity has enough power to make decisions and implement them effectively. In Costa Rica, almost any relevant executive initiative can be derailed by the legislature, or the Constitutional Court, or the General Comptroller, or the Attorney General’s Office or an endless list of institutional actors. There’s always a veto point—generally more than one—that can be activated to preserve the status quo. In Costa Rica, the bias towards policy immobility is uncommonly strong.

This system is a collective creation born out of deep mutual distrust. All political parties and social actors have converged in the construction of an inextricable maze because they know that, sooner or later, one or more of those blocking mechanisms can be put at the service of protecting their own interests. Moreover, these veto powers have a capillary nature. They reach every single level and interstice of the Costa Rican public sector, in a way that makes them very hard to reform and undo.

A personal anecdote may serve to illustrate the problem well. Years ago, as Vice President of Costa Rica, I decided to buy a flower arrangement to brighten up my drab government office before the visit of an important delegation from the European Parliament. To my astonishment, what I thought was a straightforward transaction with the corner shop ended up being a matter of high politics. After a two-hour discussion on the phone with officials at the General Comptroller, the Ministry of Finance, and the Attorney General’s Office, a clerk at the Comptroller’s office broke the news to me, in a triumphant tone, that an obscure order issued by his institution years before explicitly banned the purchasing of flowers by cabinet ministers. I put the hand in my pocket, purchased the flowers all the same, and learned in the process an unforgettable lesson on the workings of the Costa Rican state.

This veto-prone dynamic affects insignificant decisions like buying flowers but also matters of great consequence, like fiscal sustainability. For nearly two decades, starting with the appointment by President Miguel Ángel Rodriguez (1998-2002) of a blue-ribbon commission of former Ministers of Finance in 2001, the repeated efforts to introduce a tax reform drowned in political and legal quicksand, despite a vast majority of political actors long acknowledging the unsustainability of public finances. It took the near certainty of a fiscal disaster for the administration of President Carlos Alvarado (2018-2022) to finally overcome the legal obstacles—particularly the strict procedural checks imposed by the Constitutional Court—to enact a comparatively modest tax bill. Seventeen years and five administrations had passed since the days of the blue-ribbon commission.

While the cumbersome workings of the political system and public administration appear to increasingly compromise the output legitimacy of Costa Rica’s democratic institutions, a further crucial factor is eroding their input legitimacy—the very serious weakness of political representation. In a process that mirrors what has happened in many other democracies, party identities and loyalties in Costa Rica have been obliterated. Eight out of 10 Costa Ricans manifested no affinity with any political party in a recent opinion survey. The same survey detected that, as elsewhere, political parties come last in the level of popular trust enjoyed by 18 national institutions. If robust parties were once able to exert a strong centripetal force over political ambitions, their weakness is introducing irresistible incentives towards the creation of new parties that are little more than personal vehicles. Aided by lenient rules to establish parties, the electoral offer is proliferating beyond recognition. The 2022 election featured 25 presidential candidates, a remarkable number for a country that in 1986 had only six.

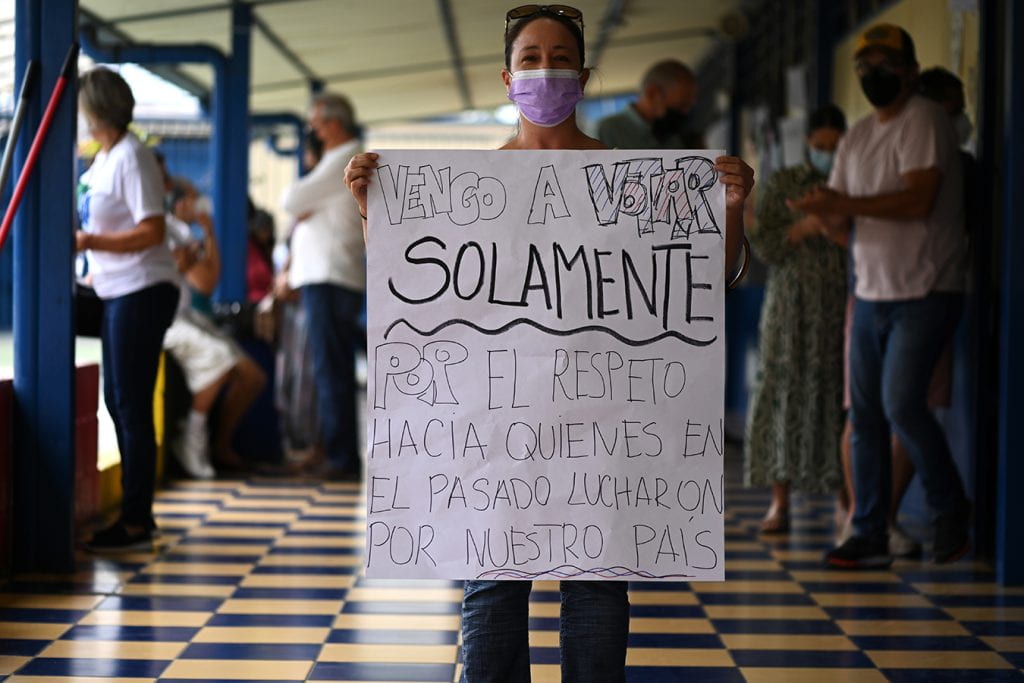

The sign reads, “I go to vote only out of respect for those who in the past struggled for our country,” April 2022, Photo credit: Jose Díaz. Instagram: @josediaz2491

The hollowing out of political representation is not helped by the electoral system. In a country where party loyalties have become almost meaningless, the prevailing closed-list PR electoral system forces voters to choose their congressional and municipal representatives (except for mayors) from fixed party slates, which don’t allow for any kind of personalized representation. This is further compounded by the very low number of members of Congress and the fact that they cannot be successively reelected, a highly unusual and questionable feature of the Costa Rican electoral system. This combination creates visible obstacles to the closeness between citizens and representatives.

The weakness of political parties, the constant proliferation of new political outfits, and the very tenuous relationship between votes and mandates have greatly eroded political accountability. Most elected officials in Costa Rica hardly have a mandate or strong incentives to stay attuned to the citizens’ demands. Citizens sense it and act accordingly—they take their demands outside of the realm of representative institutions and are lured by new political actors that promise to make their voices heard without the noise created by parties. In yet another vicious cycle, this accelerates further the demise of the party system, opening in the process obvious opportunities for populist outsiders to succeed.

By now the picture should be clear. The convergence of a dysfunctional constitutional architecture, growing fragmentation of the party system, proliferation of veto points, and grave weakness of political representation is having toxic effects in Costa Rica. The net result is the country’s diminished ability to channel social demands through institutional means, to enact much needed reforms and, ultimately, to solve real problems for real people. All of this generates acute popular exasperation, loss of faith in democratic institutions, and an ever-stronger temptation to experiment with anti-system political options. Recent survey data tells this story in an eloquent and disturbing way. According to regional poll Latinobarómetro, between 2020 and 2023, support for democracy shed 11 points in Costa Rica (from 67% to 56%). At the same time, the proportion of the population that is either indifferent between a democratic and an authoritarian government or squarely prefers autocratic rule, climbed by 15 points (from 23% to 38%). This was, almost certainly, the worst deterioration in democratic sentiment in Latin America in this period.

The declining performance of Costa Rica’s political system may or may not be the cause of the festering distributional and security concerns that afflict the country, but, at the very least, is not contributing to redress them. Thus, in a way, Costa Rica’s fundamental problem is a procedural, rather than a substantive one—the arteries of its political system are clogged, rendering inevitable the decay of the patient in multiple ways. Reforming the workings of this system is a pre-requisite to address all the other pressing issues and allow the country to return to its past successful trajectory.

Which Way Now?

Costa Rica is at a crossroads. That it has become a different country from the one that was long seen as an exception in Latin America has been evident for a while. It’s been years since branding Costa Rica as an egalitarian, safe or reasonably well-educated society became a stretch. But the growing disdain for democratic norms currently seen in President Chaves’s behavior as much as in popular political attitudes is threatening even deeper certainties about the Costa Rican identity. This is disquieting but by no means unprecedented. That democracy would fall into a vortex of violence and repression in Chile and Uruguay was once considered unthinkable in Latin America. One of the signs of our troubled times is, precisely, the mounting evidence that democracy is under assault even in some of its most august locations, amidst the indifference or even the glee of large segments of the population. Whether Costa Rica still is a regional exception is, in a way, a lesser question. The more important question is whether we, Costa Ricans, can still protect and reinvigorate the most valuable political legacies from our past in the face of acute disaffection and populism.

I think we can, but we need to recognize the nature of the problems we face. We should start by discarding the pernicious narrative that sees the country’s recent travails as the sole result of personal failings of inept, indecisive and corrupt political leaders. As seen above, the problem is not personal, but systemic. Rooting for an incorruptible avenger, equipped with divisive rhetoric, will do little for the country. Quite the opposite. As in the 1980s, a set of broad political agreements on key issues—from how to confront spiraling crime rates to how to repair a crumbling public education system and integrate a bifurcated economy—is urgently needed. Yet, unlike four decades ago, those agreements are now hampered by an unwieldy political system. That’s why political reforms are needed.

Costa Rica is at a crossroads. How will it face the cloudy panorama? Photo by June Carolyn Erlick

If the arteries of the Costa Rican body politic are to be unclogged, four types of political reforms should be undertaken as a matter of priority:

First, it is high time to discuss the continuity of the presidential system or, at a minimum, its profound reform. As elsewhere, the convergence of a presidential setup with an increasingly atomized party system has become deeply problematic in Costa Rica. The key here is understanding that the fragmentation of the party system is unlikely to be reversed any time soon, if at all. Hence, it is critical to counterbalance fragmentation with incentives for coalition making, in ways that allow for the efficient construction of stable legislative majorities. Such incentives are part and parcel of a parliamentary system, where the emergence and survival of the government depends on having a legislative majority. But it is just as possible to go for the adoption of a semi-presidential system, as has indeed been suggested by previous political reform efforts in Costa Rica. If the presidential system is to be retained despite its glaring shortcomings, then easing the extant rules to form electoral coalitions, which have been rarely used in the past four decades (The last coalition registered to contest a national election was Izquierda Unida in 2006), and carefully enhancing the Executive’s legislative prerogatives ought to be considered.

Second, political representation should be revamped in several different ways. Increasing the number of members of the Legislative Assembly, or at least creating a mechanism to revise it in line with population growth, is an obvious option, albeit an unpopular one. The current PR closed-list electoral system probably should be dropped for one that allows a more personalized representation, while retaining incentives for the cohesion of political parties. Serious thought should be given to the adoption of a Mixed Member Proportional Representation System, which combines single-seat constituencies with party lists, as seen in Germany and many other democracies. The introduction of a measure of personalized representation is the key to correcting one the key anomalies that erodes political accountability in Costa Rica—the absence of successive legislative reelection.

Third, the robustness of parties should be enhanced by rendering more demanding the requirements to register new parties and shifting the center of gravity of the comparatively generous system of public funding from subsidizing the parties’ electoral activities to supporting their organization, territorial presence and programmatic development.

Fourth, some of worst excesses of the Costa Rican “vetocracy” should be rationalized. This is a huge and delicate area of reform. For example, a strong case can be made to curtail some of the prerogatives of the Constitutional Court, including the widespread use of its powers to suspend executive decisions by the mere admission for study of a case against them. Even stronger are the arguments to reform the detailed ex-ante vigilance exerted by the General Comptroller over public disbursements and replace it with more strategic oversight and stronger reliance on the ex-post accountability of public officials. Yet, on this a note of caution is warranted. The hypertrophied checks and balances that have proven costly for the output legitimacy of Costa Rica’s democracy over the past decades are the same ones that today are restraining some of the most questionable impulses of President Chaves’ administration. The vitriol hurled by Chaves towards the Constitutional Court and the General Comptroller on an almost daily basis is the proof that, for good and ill, checks and balances do exist in the Costa Rican political system. Thus, when reforming this cumbersome setup, we must take into account that its ability to curb the worst excesses of populism may not count for everything but does count for something.

The enactment of many of these reforms requires constitutional amendments and, hence, qualified legislative majorities. This poses thorny procedural questions. Does pursuing this agenda require a constitutional convention? Possibly, but not necessarily. Many reasons, including Chile’s recent experience, argue against the option of a constitutional convention, which would amount to a huge political gamble in a polarized and fragmented environment. A gradual agenda of partial reforms looks desirable and possible until one considers that the inevitable agents of this program –political parties and, more broadly, political elites—have been very reluctant to modify the current constitutional and electoral architecture. Arguably, over the past 20 years of increased party fragmentation not a single significant political reform has made it through Congress.

Costa Rica faces a difficult choice. If profound political reforms are not enacted, all the other substantive reforms that are sorely needed are unlikely to happen and the country will continue to slide down the perilous path of decreasing governability and support for democracy. Yet, if those political changes are to happen at all it may well be that Costa Rica needs to gamble its future on a constitutional convention, where not just the faulty aspects of its institutional framework, but also the highly successful ones, will be on the chopping block. Moreover, such a convention would likely take place at a time when political forces less committed to the country’s traditions of tolerance, civility and respect for the Rule of Law have the wind at their back.

There is no obvious solution to this quandary. But Costa Rica does need to come to grips with these issues with a sense of urgency that the election of President Chaves has only heightened. Yet, as one of the characters in the movie “American Beauty” quipped, one should never underestimate the power of denial. And it so happens that the temptation to engage in denial and self-soothing stories is considerable in a country that once was an almost successful underdeveloped nation and an exception in a troubled region.

Kevin Casas-Zamora is the Secretary General of the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA). He is former Vice President and Minister of National Planning and Economic Policy of Costa Rica.

Related Articles

Homecoming and Public Education: The Cancel Culture (of class time) in Costa Rica

When I returned home on my sabbatical, I couldn’t stop thinking about Svetlana Boym’s extraordinary book, El futuro de la nostalgia.

Crisis of Citizen Insecurity in Costa Rica: A Challenge to the Model of Demilitarized Democracy

I began my political and public service career thirty years ago as Minister of Public Security, the first woman to ever hold that post in my country, Costa Rica.

Editor’s Letter: Is Costa Rica Different?

Is Costa Rica different?