Managua and Washington in the Early Sandinista Revolution

When I returned to the United States after an event-filled two plus years as the United States Ambassador to Nicaragua some 37 years ago, the Sandinista humor magazine the Semana Comica featured a full-page cartoon entitled “El Regreso,” (the Return), showing me being spanked by Ronald Reagan in the admiring presence of Henry Kissinger and Jeanne Kirkpatrick.

I was not exactly the poster boy for the Reagan administration’s policy.

I had arrived in Managua on the 15th of March 1982, on the first day of the “secret” war against the Sandinistas. While I was in the air from Miami to Managua, Daniel Ortega declared a state of emergency because that morning a CIA-sponsored operation had led to the blowing up of bridges connecting Honduras and Nicaragua.

It was all downhill from there. I had been briefed about President Reagan’s “finding” on Nicaragua which led to increasingly aggressive actions against the Sandinistas. These measures were explained to me and to the Congress as disincentives for further Sandinista support for the FMLN in El Salvador and as a way to hold the government to its original pledge of a mixed economy, multi-party democracy and a non-aligned foreign policy.

By the time I arrived all of these commitments seemed in the White House to have been abandoned by the revolutionary junta in Managua. In fact, the President’s advisors had a different agenda in mind: regime change, but this was not immediately apparent either to me or to my bosses in the State Department.

The current Trump administration has once again focused its attention on Nicaragua and the Sandinista “comandante,” Daniel Ortega, who for the last decade has once again been President of Nicaragua and who once again is in the cross hairs of U.S. Central America policy.

In 2019—as in 1982—we are faced with many of the same dilemmas. Is regime change a viable strategy for U.S. foreign policy? How are we to assess the successes and shortcomings of a regime which proclaims lofty ideals yet often resorts to repressive practices? And finally how does the legacy of history constrain what we can do to create a better future for countries which proclaim themselves revolutionary, but end up impoverishing the citizens they claim to have saved?

Once again the United States is engaged in trying to bring about regime change. Once again the desired U.S. outcome is shrouded in ambiguity and uncertainty. Once again the glass is half empty for some, half full for others.

Nicaragua today was breathlessly dubbed the junior member of the Troika of Tyranny by National Security Advisor John Bolton late last year. As in the 1980s Nicaragua is again linked with Cuba in the eyes of the U.S. government, only to be joined in recent months by the Bolivarian Revolution of Hugo Chávez and Nicolas Maduro.

When I arrived in Nicaragua in 1982, I was somewhat of a neophyte to revolution. As a graduate student at Oxford, I had explored and written a thesis on the unsuccessful French efforts to overthrow the Bolshevik Revolution. However that remote academic expertise was not known to my contemporaries either in Washington or Managua and it did not occur to me that it might be relevant.

The Soviets decided that I was a committed Cold Warrior because of my previous position as coordinator of counterterrorism in the Carter Administration. They assumed that I was an experienced and committed regime-changer, or so , at least Pravda charged and many in the Sandinista movement believed. Nothing could have been farther from the truth. I was a rather naïve 48-year-old foreign Service Officer, with extensive experience in the Indian Sub-continent and virtually no knowledge of Latin American history, culture or politics.

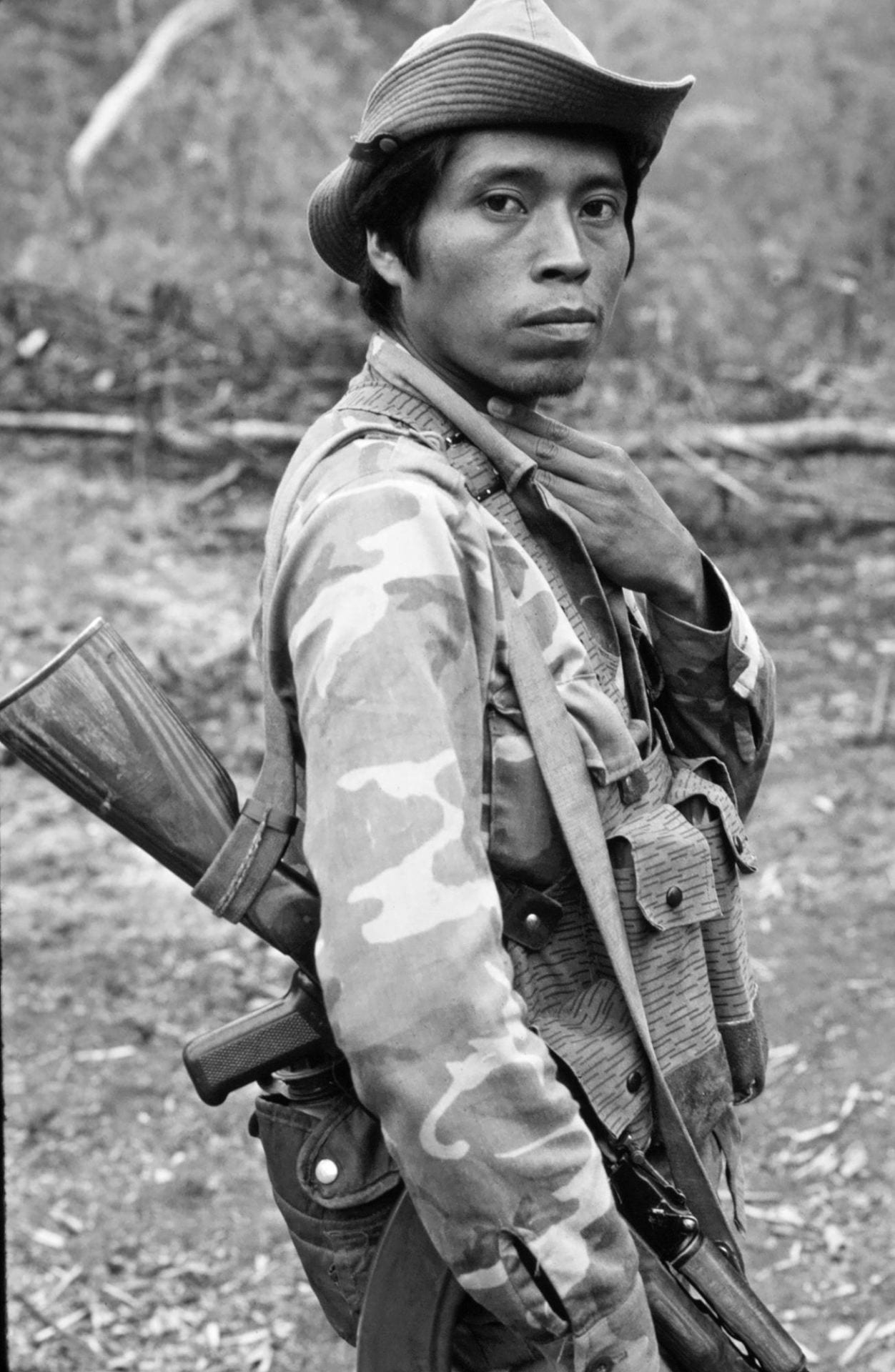

U.S. policy then, as in some ways now, oscillates between two strategies: negotiation and pressure. In Nicaragua the latter ultimately won out. At the same time as we were organizing the counter-revolutionary “contra” effort in Honduras and Costa Rica, we were presenting a rather prickly olive branch to the Sandinistas offering to live with the revolution if it upheld its pluralist promises and halted the export of the revolution. At the same time that we were urging the Contadora powers to continue their efforts for a region-wide negotiated settlement, we were ratcheting up pressure, eliminating Nicaragua’s sugar quota, terminating all aid except to the private sector and steadily increasing direct pressure by blowing up the oil pipeline into Managua’s refinery, mining Nicaragua’s ports and developing an effective contra fighting effort. It was against this background that my “Mission Impossible” played out.

The United States throughout that period was obsessed by the Cold War and its implications. The Administration accepted the assumptions of the domino theory which had led us so far astray in Vietnam and Southeast Asia. The Administration was convinced that if the communists established a base in Central America, they would push relentlessly north towards Mexico and south to the Panama Canal. If that were to happen, U.S. security would be gravely threatened.

The Administration also suffered from a malady which still infects our Latin American foreign policy: backyard syndrome. Today no one seriously thinks communism is on the march northward until even San Antonio might be at risk. But we still regard the Caribbean and Central America as our backyard where certain behaviors by local governments are inadmissible. The current Administration’s focus on the Troika of Tyranny (Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua) is evidence of that fact. That approach has been true at least since 1905 when Theodore Roosevelt announced his corollary to the Monroe Doctrine asserting a right for the United States to intervene in cases of “chronic wrongdoing” and to act as an international police power.

Diplomacy is the art of managing ambiguity and complexity to achieve outcomes favorable to one’s national interest. Ambiguity there was aplenty in the early 80’s in Nicaragua. At the heart of that ambiguity was not only the young Daniel Ortega, one of the ruling triumvirate and the nominal head of state, who came from a bourgeois family and was educated by Jesuits at the Central American University.

It was also Tomás Borge, the seasoned revolutionary and founder of the FSLN. Hundreds of foreign visitors came to see him. From the United States, they included senators and congressmen, business leaders, missionaries and concerned citizens. All were fascinated by this rotund cigar-smoking Minister of the Interior. All had heard of his ruthless suppression of enemies and his reliance on Cuban and East German apparatchiks. Few, however, were prepared for his personal charm or his official office decorated with a wall of crucifixes, or saw his inner office where besides the drinks trolley and the bottles of Chivas Regal Scotch were two books: the Bible and the Fundamentals of Marxism-Leninism.

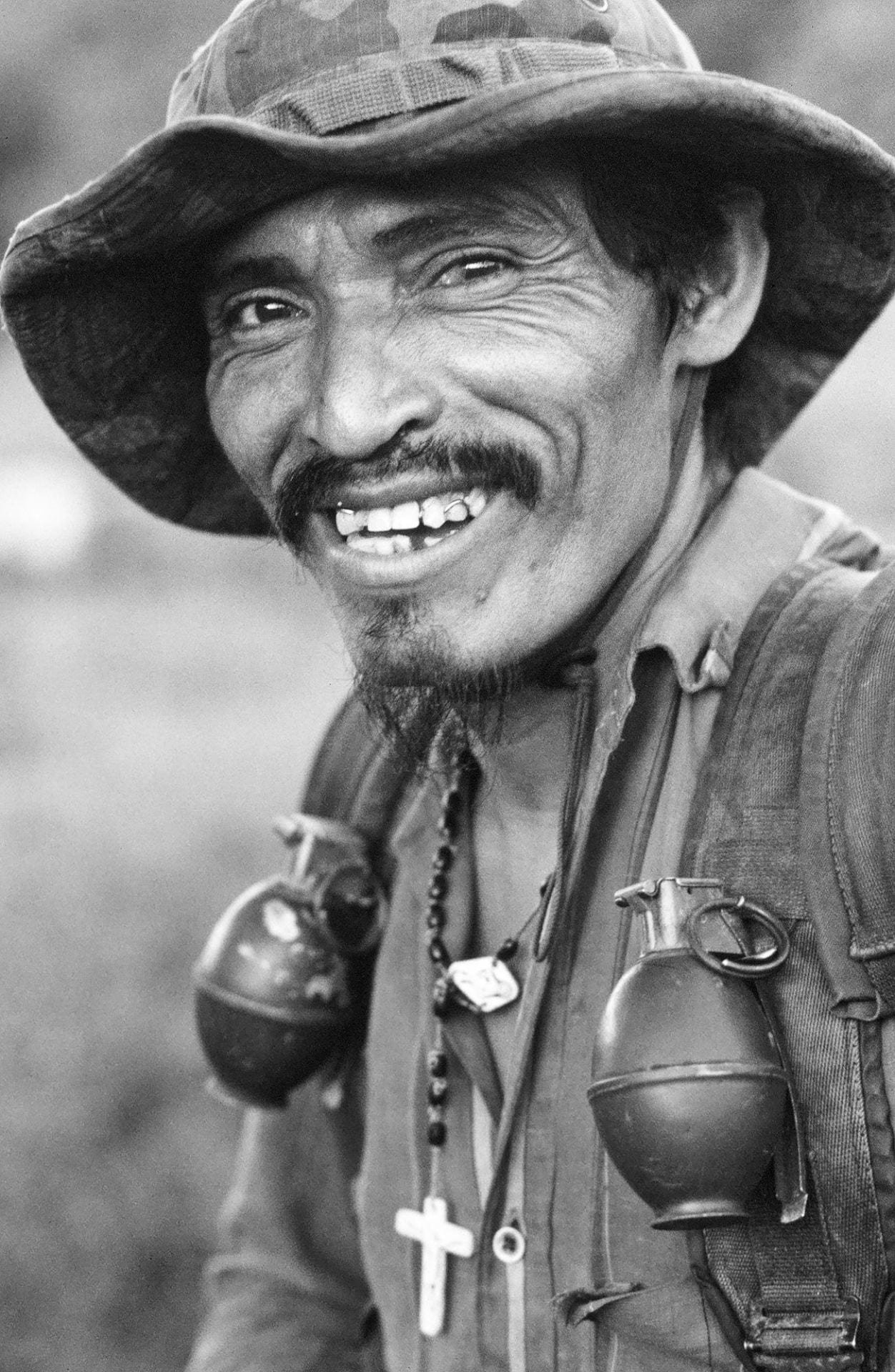

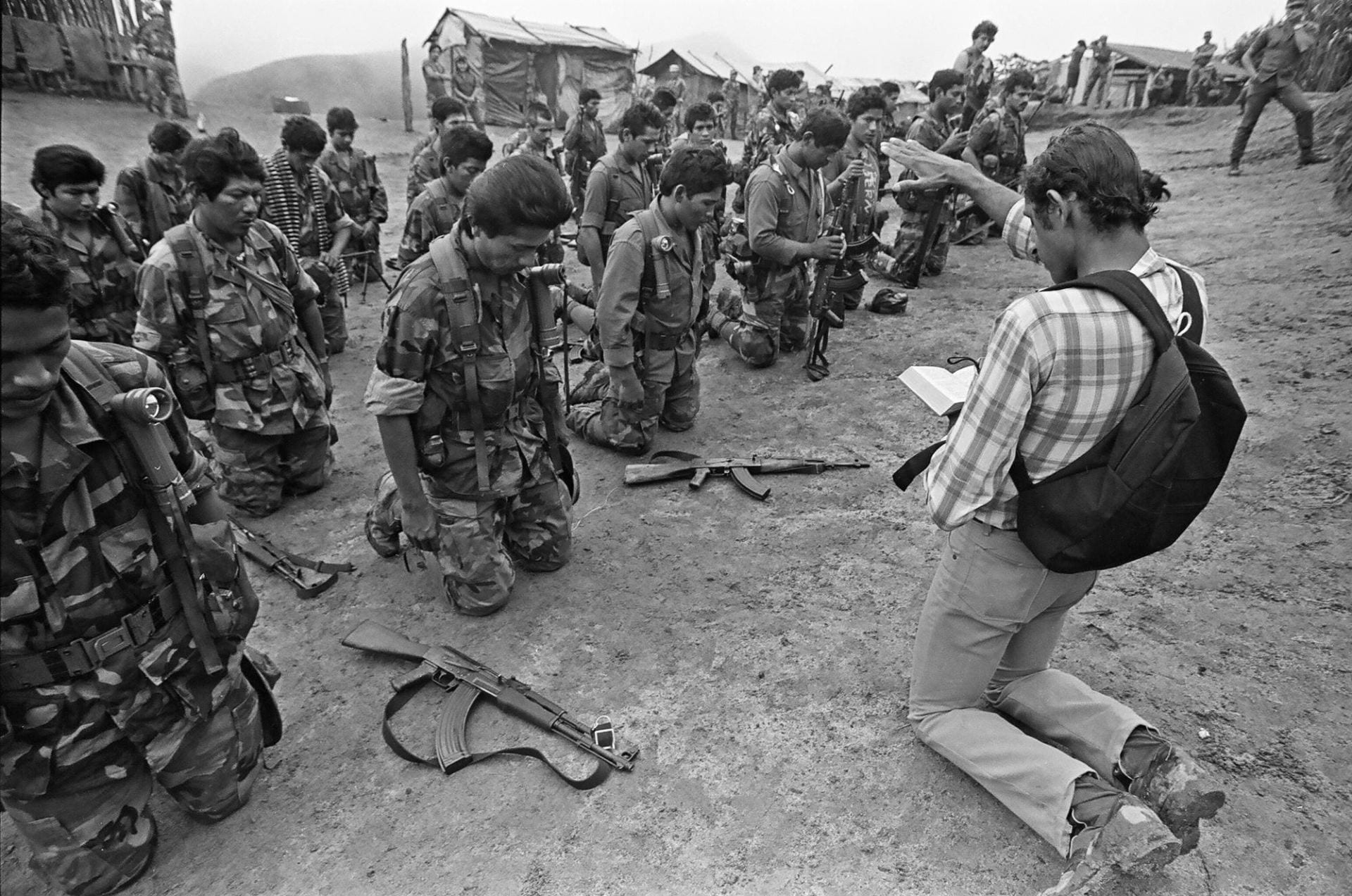

Indeed, the whole question of the relationship between religion and the revolution was one which bedeviled the Administration’s efforts to roll back communist advances in Central America. Hardly a week went by during my tenure without the visit of a delegation of American religious leaders. They were priests and nuns, pastors and rabbis, lay men and women. Even the occasional bishop. Most believed that the revolution had done some good, by overturning past oppressive social and political structures, educating the masses through the literacy campaign, and extending the benefits of health care to marginalized villagers and urban dwellers. One such delegation arrived in the first week of my stay. After I tried to explain the objectives of President Reagan’s policies, they asked me if they could pray. I was a neophyte at office-praying and, with a little hesitation, agreed. There I was alone in my office with a deeply religious peace delegation, holding hands and solemnly praying that the Reagan Administration would see the errors of its ways.

Most groups were polite and respectful, listened to my presentation even when they disagreed. But a member of one such group from the film industry in Hollywood, angrily told his companions that if there were ever to be Nuremberg trials after the current crisis had ended, the U.S. ambassador would surely be one of the guilty. A mission which was difficult enough at the political and diplomatic level became even more difficult at the emotional and moral level. Needless to say, one does not like to be denounced as a war criminal. My staff hated the moral intensity of both the supporters and opponents of the regime, even when they shared some of the criticisms of U.S. policy or of the Sandinista regime.

If it was Mission Impossible for the U.S. Ambassador, it was also Mission Impossible for the Catholic Church. There were several priests in high positions in the government, including the Foreign Minister Miguel D’Escoto and the two Cardenal brothers in the Culture and Education ministries. Liberation theology was very much in vogue and the writings of the Peruvian priest Gustavo Gutierrez were much admired. However, there were also many Catholics who saw the revolutionaries as deeply hostile to the Church and to its doctrines. These views were reinforced by the bizarre incident in which the Archbishop Obando’s Secretary, Father Bismarck Carballo. was photographed by Sandinista Television fleeing naked from the home of a woman parishioner after an alleged romantic tryst and, of course, by the treatment of the Pope who was shouted down at the papal mass in Managua. The papal nuncio, then as now, found himself in a keying mediating position trying to bridge the wide gap between Christians in and outside the Revolution.

Against this background getting the story right was one of the central responsibilities of the Embassy. We believed that Washington could not possibly get its policy right without accurate and informed analysis of the situation on the ground. This was a particular challenge for the Embassy in Managua. To those in Washington and beyond who were suspicious of the Sandinistas, our reporting was often thought to be biased. At one point B’nai Brith, the Anti-Defamation League, went to the New York Times to complain that the Embassy had not reported on systematic anti-Semitism in Sandinista Nicaragua. The story appeared on the front page of the Times, and the Department immediately became concerned that perhaps we actually had covered up a serious problem. We carried out an immediate investigation and concluded that the Sandinistas were anti-Zionist (They did not recognize the State of Israel and had allowed the Palestinians to open an office in Managua) but no one we could find, even the Sandinistas’ most rabid opponents, believed there was or ever had been any anti-Semitism. Elliot Abrams, then the Assistant Secretary of State for Human Rights, descended on the Embassy to check for himself whether the Embassy’s reporting and analysis were correct. He remained skeptical of our reporting.

Subsequently, I was summoned to the White House where a senior White House official complained to me that we were reporting too much good news from Managua. Urging me to help the president defend his policies, she told me in no uncertain terms that I should increase my reporting of bad news. I replied that we would report all the news, both good and bad, but that we would not skew our reporting one way or the other. Needless to say, this did not satisfy the White House.

The truth is that we did assiduously report on Sandinista violations of human rights, on their attacks on press and political freedoms, on their harassment of certain parts of the private sector and on their generally intolerant attitude to opposition political parties. We also tried to report faithfully on those aspects of Sandinista policy that seemed to be offering positive benefits to the people of Nicaragua: the literacy campaign, the health reforms, the barrio-level self-government. For those who believed that nothing good could come out of the Revolution, these reports were seen as fuzzy-headed and misguided attempts to undermine the Reagan Administration’s strategy in Central America. It was virtually impossible in that atmosphere to get the story right. The Mission’s reporting was scrutinized for signs of feeble-minded sympathy with the Revolution and a lack of enthusiasm for U.S. policy. My public appearances were scrutinized for signs that I had or had not walked out when public speeches condemned the United States and its support for the contras. Critics wondered whether I did or didn’t I stand when the Sandinista hymn was played and the crowd solemnly referred to the Yankee as the enemy of mankind. Some wondered why I did not protest the endless series of cartoons in El Nuevo Diario, Barricada and La Semana Comica depicting me as a dim-witted accomplice to the CIA’s violations of international law and Nicaragua’s territorial sovereignty. Mission Impossible indeed it was.

It was, of course equally difficult to satisfy the critics of the Administration’s policy. They saw our sanctions as impoverishing the Nicaraguan people and our support for contras incursions and attacks as violations of international law. They could not understand why we did not recognize the youthful and idealistic enthusiasm of the Sandinista for what it was in their eyes: well-intentioned, idealistic and morally powerful. They saw us as blinded by anti-communist prejudice. As a result, week by week they came and called on me. They protested and held demonstrations outside the embassy to denounce U.S. policy. They organized candlelight vigils on the border calling for peace.

The impossibility of the Embassy’s position, or rather of my position, became apparent when the Kissinger commission arrived in Managua in October of 1983. Charged by the President with recommending policies for resolving the Central American crisis, the Commission contained some of the biggest names in American politics including Lane Kirkland, the president of the AFL-C IO; Henry Cisneros, the mayor of San Antonio; Senators Dominici and Bentsen and Congressmen Barnes and Kemp, plus academics such as Jeanne Kirkpatrick from Georgetown and Carlos Diaz-Alejandro from Yale.

The day the Commission spent in Managua was a visit fraught with challenges which exposed the many ambiguities of the situation. My own presentation to the commission on the morning of its arrival argued that a negotiated deal with the Sandinista regime might be achieved at least with respect to its direct support of the revolutionaries in El Salvador and maintenance of a relatively open society and our own acceptance of the Sandinista regime itself. The commission was in no mood to hear that message. John Silber, the president of Boston University, pointedly challenged me to explain how my views were consistent with those of the White House. The Commission was more impressed by Enrique Bolanos’ presentation on the abuses of the Sandinista regime and his handing round of the first day cover of a recent Nicaraguan postage stamp commemorating the hundredth anniversary of the death of Karl Marx. That for the Commission was proof that the communists were in control. I did not have the wit to point out that the Sandinistas had also issued a series of George Washington stamps.

The Commission had made up its mind before it arrived. They were sure that they were up against a Marxist Leninist regime in the process of consolidating itself into a state on the Soviet/Cuban model. The Commission’s experiences , particularly the brilliantly detailed intelligence briefing by the head of Sandinist intelligence, only confirmed their view of Cuban penetration and control. Their final meeting with Daniel Ortega was a disaster, following an equally unsatisfactory meeting with Foreign Minister D’Escoto in which each side accused the other of lying.

Comandante Ortega lectured the Commission for forty minutes on the tragic history of U.S. policy over the previous 125 years, from William Walker’s takeover in the 1850’s, through the Marines’ arrival in 1909, 1912 and beyond, the death of Sandino and the support of the Somozas. The Commission was in no mood to be lectured about the evils of the past. They simply walked out with no dialogue having taken place. They had had enough and what might have been an opportunity for dialogue ended in acrimony and deepened distrust.

Reading its report 35 years later I am struck by the sophisticated and nuanced understanding of the underlying social and economic issues that Central American countries confronted. Were it not for its preoccupation with the Cold War dimension of the crisis, the report was remarkably balanced. To be sure, it stressed the threats to regional stability from a Marxist Sandinista regime and its Cuban and Russian backers, but it also went to great lengths to stress the need for a major long term commitment of the United States to the social and economic development of the region. It deplored past U.S. association with regimes such as that of Anastasio Somoza and recognized that if the United States really wanted stability, it would have to be a major supplier of economic and commercial assistance to the region with a minimum five-year horizon. Had those themes been picked up and had sustained aid to Central America been agreed to, some of the problems we are now encountering might have been avoided or at least ameliorated. Unfortunately when the Sandinistas were eventually voted out of power in 1990, the United States largely lost interest in the region. We are reaping the whirlwind of that neglect in the refugee and gang crises we are now facing.

There is not much use in crying over spilt milk. Opportunities to create a more stable Central America existed four decades ago. They were lost. Both sides could not see beyond their ideologies. Neither could escape from its history. The Sandinistas believed that they were a vanguard party and that history had entrusted them a revolutionary mission.

We saw that mission as a fundamental rejection of and threat to our western liberal values. They could not escape from the troubled history of Yankee intervention. We could not escape from Vietnam and the experiences of the Cold War. Bridging the historical, ideological and emotional divide between us was more than I or my colleagues could do. Try as we could, the Mission was always impossible.

This article was adapted from the keynote address Ambassador Quainton delivered on May 2 to the conference on Nicaragua at Brown University, “Nicaragua 1979-2019: the Sandinista Revolution,” organized by Stephen Kinzer.

Spring/Summer 2019, Volume XVIII, Number 3

Anthony Quainton is Distinguished Diplomat in Residence at American University in Washington DC in the School of International Service. Quainton spent 38 years as a member of the United Stated Foreign Service including posts in Nicaragua, Peru, Kuwait and the Central African Republic. He also served as Director General of the Foreign Service, Assistant Secretary of State for Diplomatic Security and Coordinator of the Office for Combating Terrorism. He retired from the Foreign Service in 1997 and subsequently was President and CEO of the National Policy Association from 1998 to 2003.

Related Articles

The University and the Nicaraguan Crisis

English + Español

University youth were the first to rise up in April in Nicaragua. Then other young people followed en masse, followed by the rest of the population. The young students woke up an entire country. “They are students; they are not delinquents!” became the first slogan that…

Nicaragua TEMPLATE: Single Language Article

English + Español

A one or two sentence blurb about the article

3, 2, 1… poemas

Manual para sobrevivientes…