A Review of The Price of Gold: Mechanized Mining in El Chocó, Colombia

Images of a Pawned Future

The Price of Gold: Mechanized Mining in El Chocó, Colombia by Steve Cagan and Mary Kelsey (2020, 96 p.)

I loved to be in the Chocó. My work on a biodiversity conservation project allowed me to travel frequently to the seldom-visited northwest fringe of Colombia. The humid air, the calmness, and everything about this place made me feel at ease. To navigate the majestic Atrato River, which collects the waters of one of the rainiest zones on the planet and slowly carries them to the Caribbean, was a blessing. The jungle was always present and the inhabitants—with their lilting accents, their friendly treatment and disarming transparency—made the experience a real treat. More than the poverty that is the image many have of Chocó, the energy and wisdom I was discovering amazed me and left me hungering to know and learn more. These journeystook place two decades ago already, but the enchantment is not forgotten, nor is a certain sadness caused by the sensation that Chocó is condemned to bear the burden of its misfortunes.

Steve Cagan and Mary Kelsey are regular visitors to this region, who also succumbed to its charms. With their book—The Price of Gold—I was able to return, relive memories and sensations, as well as to better understand the nature of mechanized mining that has caused so much havoc. The many images in the book are an excellent presentation of Chocó for those who do not know it and a source of reaffirmation and surprises for those familiar with the region. In the last 15 years, the two U.S. artists have repeatedly visited several communities located for the most part in the middle basin of the Atrato River, and they have photographed and drawn what they have seen. Cagan’s color photos and Kelsey’s black-and-white drawings, along with the short text that accompanies them, allow the reader to travel with them and also feel anguish for the wounds left by the excavators and dredges that have extracted gold since 1990s.

In those years, “retrero” miners from the lower Cauca River basin, in the state of Antioquia (of which Medellín is the capital), began to arrive; the name “retrero” comes from the Spanish word that designates their technology of choice, retroexcavadora—excavator. Before they entered in numbers to the Atrato, they ventured into San Juan, the Chocó’s great mining basin, and also into the south of the Colombian Pacific Coast. They left their awful imprint: large spaces devoid of vegetation, pure gravel and dirt, with huge pools of stagnant water; landscapes of destruction previously teeming with life. Cagan and Kelsey have witnessed the advance of this type of mining and describe it to us. Their visual testimony is clear and shocking. The text is straightforward and an easy read. The price of gold is not only environmental, but social. Through this book, I learned that this form of mining has transformed peasants, who were farmers who sometimes panned for gold, into full-time miners. Moreover, this mining has sparked feuds among relatives and neighbors, and has generated anxiety about the future. “This is all fine,” a man named Ulises tells the authors. “But when the gold gives up, what will happen then?”

The fleeting depiction of characters like Ulises provides warmth to the narrative and helps to transmit the passion, affection and respect that imbue this book, which is difficult to categorize. Although it is a large-format volume full of beautiful photography, it was not designed as a coffee-table book. Neither is it a travelogue and much less a book dominated by painstaking analysis. It is a testimony and a denunciation and, at the same time, a homage to the people of Chocó.

The photographs are quite varied: there are portraits of people attending meetings or working in mining, as well as in farming and fishing. They portray Black people, as well as the Indigenous population. There are many colors and diverse places, all shown in varying sizes within the layout of the book. Landscapes are few and far between and the majority of them are desolate. Cagan prefers that the camera get close to its subject, seeking a certain intimacy.

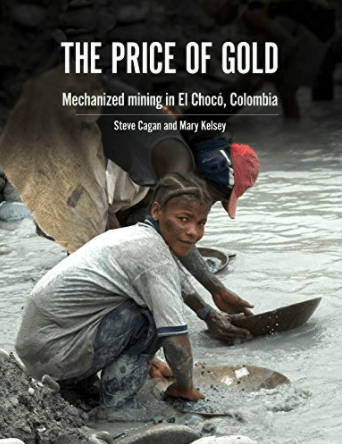

The cover of the book is an indication of the type of image that predominates. It is not the prettiest photo and it isn’t colorful either. In it, we can see a woman curled up with her gold pan in the water, and although she seems taken by surprise, there’s a bit of artifice: she looks directly at the reader, thus establishing a connection between the viewer and this artisanal miner.

The drawings reinforce the sensation transmitted by the photos: the authors want to be immersed in this reality, rather than observe it from a distance. It is not difficult to imagine Kelsey sitting and drawing scenes of daily life in the mine, in the river, in the jungle, in the plantain groves and in meeting rooms. These drawings manage to relay the calm movement that marks the rhythm of life in Chocó.

But I missed having captions for the images. I would have liked to know where and when each photograph and drawing were made. Without this information, part of the documentary value is lost, at least for me, a historian accustomed to locate information in time and space. Luckily, a few of the drawings have handwritten notes on where they were made: “10.8.16 Napipí” can be read, for instance, below the waters of a river where three women are washing clothes.

The photographs of mining techniques are particularly useful to understand the transformation suffered by the geographical heart of Chocó in the last decades. Machines, rather than people, take center stage. These photos illustrate, and this measure allow one to grasp, how these technologies work. The texts are an excellent complement to understand artisanal mining, which is carried out with pans, portable sluices (matracas) and pumps, as well as to decipher the functioning of small dredges, excavators, “dragons” (as local people call the dredges after the Spanish word “dragas”), and the elevadoras (huge sluices).

Although the texts have the virtue of being simple, they sometimes suffer from being simplistic. The authors evoke a traditional idyllic world shattered by capital interests (and under the constant shadow of the armed conflict that has caused so much pain in Chocó since the end of the 1990s). In the face of this panorama, only the alternative of resistance remains. Although there is no doubt that mining has caused an environmental catastrophe, creating tensions in the communities and increasing their vulnerability, the past was not perfect. The idea of a traditional world impedes seeing that changes have always happened, and this vision makes it difficult to understand the causes of what is happening. Ángela Castillo explains, in a book she co-authored with Sebastián Rubiano by the name of La minería de oro en la selva: Territorios, autonomías locales y conflictos en Amazonia y Pacífico, 1975- 2015 (published by Ediciones Uniandes in 2019), that, at least in the San Juan basin, the owners of the excavators negotiated with the local community, recognizing and respecting customary mining rights. The residents accepted the excavators because, contrary to what the authors assert, their benefits extended to the majority of the people, although these benefits were short-lived and vastly outweighed by the social and environmental costs that this type of mining generates.

The limitations of this vision are observed in the insinuation that the “retreros” didn’t keep their part of the bargain in not restoring the vegetative cover. However, people knew this was impossible: they had seen what had happened in neighboring communities, and even then, they were sold on the project. Cagan and Kelsey, like me, enjoy many of the advantages of consumerist capitalism (like being able to visit Chocó); people there also want their slice of the pie. The problem is quite complicated and not to recognize this fact makes it difficult to begin any effective action to remedy the damage and to find a better path.

The book bears witness to a tragedy. As the authors say, after the machines pass through, the sounds of the jungle disappear and a sense of loss, rather than well-being, hangs in the air. I would have liked to read more about the experiences of the authors, our guides on this journey. I also would have been glad to hear just a bit more of local voices, especially in the last part devoted to testimonies. In the end, it is this human wealth that gives a hopeful tone to the book. The efforts of those who, like Father Remo Segalla, have tried, although unsuccessfully, to limit the the disaster, must be praised. The same is true of those who have supported processes to achieve sustainable mining or who have sparked hope by contributing to the court judgement handed down that the Atrato River is legally subject to rights. Cagan and Kelsey use the power of their images to remind us—and to make us feel—what has been happening in the Chocó. It is an achievement that should be applauded. Hopefully The Price of Gold will have the wide audience it deserves.

Una reseña de El precio del oro: minería mecanizada en el Chocó, Colombia

Imágenes de un futuro empeñado

por Claudia Leal

Me encantaba ir al Chocó. Mi trabajo en un proyecto de conservación de biodiversidad me permitía ir con frecuencia al margen noroccidental de Colombia, que es poco visitado. El aire húmedo, la calma, todo me hacía sentir cómoda y tranquila. Navegar el majestuoso río Atrato, que recoje las aguas de una de las zonas más lluviosas del planeta y las lleva lentamente hasta el Caribe, era una dicha. Disfrutaba viendo la selva y escuchando el acento acogedor de los pobladores, su trato amable y transparencia desarmaban.

Más allá de la pobreza con la que muchos identifican al Chocó, la energía y la sabiduría que estaba descubriendo me dejaban siempre admirada y deseosa de conocer y aprender más. Eso fue hace ya casi dos décadas, pero ese embrujo no se olvida, así como tampoco una cierta tristeza causada por la sensación de que el Chocó está condenado a cargar con sus males.

Steve Cagan y Mary Kelsey son asiduos visitantes a esa región, que también sucumbieron a su encanto. Con su libro—El precio del oro—pude regresar, revivir recuerdos y sensaciones, así como entender mejor la minería mecanizada que ha causado tantos estragos. Las innumerables imágenes que lo componen son una excelente presentación del Chocó para quien no lo conoce y fuente de reafirmaciones y sorpresas para quién está familiarizado con él. En los últimos 15 años estos dos estadounidenses han visitado repetidas veces a varias comunidades ubicadas en su gran mayoría en la cuenca media del río Atrato, y han retratado y dibujado lo que han visto. Las fotos en color de Cagan, los dibujos en blanco y negro de Kelsey y el texto breve que las acompaña, permiten al lector viajar con ellos y sentir angustia por las heridas que dejan las retroexcavadoras y dragas que han extraído oro desde la década de 1990.

En esos años empezaron a llegar del Bajo Cauca antioqueño los “retreros”, es decir, los mineros dueños de retroexcavadoras. Antes de entrar con fuerza al Atrato, incursionaron en el San Juan, la gran cuenca minera del Chocó, y también en el sur del Pacífico colombiano. Empezaron a dejar sus terribles huellas: grandes espacios desprovistos de vegetación, puro cascajo y tierra, con grandes piscinas de aguas estancadas; paisajes de destrucción donde antes pululaban infinitas formas de vida. Cagan y Kelsey han sido testigo del avance de ese tipo de minería, nos lo explican y retratan. Su testimonio visual es claro e impactante. El texto es sencillo y por eso se lee muy fácilmente. El precio del oro no es solo ambiental sino social. Con este libro aprendí que esta forma de minería ha convertido a los campesinos, que eran agricultores que a veces mineaban, en mineros de tiempo completo. Además, ha generado pugnas entre familiares y vecinos y ha generado ansiedad sobre el futuro: “Esto está bien,” le dijo Ulises a los autores, “Pero, cuando se acabe el oro, ¿qué va a pasar entonces?” (p.65)—“This is all fine. But when the gold gives up, what will happen then?”

Los personajes efímeros, como Ulises, le dan calidez al relato y ayudan a trasmitir la

pasión, el cariño y el respeto con que está hecho este libro difícil de catalogar. Aunque es de gran formato y está lleno de fotografías hermosas, no fue hecho para reposar en las mesas de centro de las salas y adornarlas. Tampoco es un relato de viaje y mucho menos un libro dominado por un análisis concienzudo. Es un testimonio y una denuncia, y al mismo tiempo un homenaje a la gente del Chocó.

Las fotografías son muy variadas: aparecen caras, personas trabajando tanto en la minería como en la agricultura y la pesca, o participando en reuniones. Los retratados son personas negras, pero también indígenas. Hay muchos colores y lugares diversos, expuestos en tamaños diferentes. Los paisajes son pocos y la mayoría de ellos son desolados. Cagan prefiere que la cámara se acerque a su objetivo, como buscando cierta intimidad. La portada es una indicación del tipo de imagen que predomina. No es la foto más bonita y tampoco es colorida, en ella está una mujer acurrucada con su batea entre el agua, y aunque parece haber sido tomada por sorpresa, queda el artificio: ella mira al lector y así se establece una suerte de conexión con esta minera artesanal.

Los dibujos refuerzan la sensación, que dan las fotos, de querer adentrase en esa realidad, más que de observarla desde la distancia. No es difícil imaginarse a Kelsey sentada dibujando las escenas de la vida cotidiana en la mina, en el río, en la selva, en la platanera y en los lugares de reunión. Estos dibujos logran trasmitir el movimiento sosegado que marca el ritmo de la vida chocoana.

Pero me hicieron falta pies de imagen. Habría querido saber dónde y cuándo fue hecho cada dibujo y tomada cada fotografía. Sin esa información pierden parte de su valor documental, al menos para mí, que soy una historiadora, acostumbrada a ubicar la información en el tiempo y en el espacio. Por suerte, unos pocos dibujos tienen escrita a mano esa ubicación: “10.8.16 Napipí”, se lee, por ejemplo, debajo de las aguas de un río donde tres mujeres parecen estar lavando ropa.

La fotografías de las técnicas mineras son particularmente útiles para entender la transformación que ha sufrido el corazón geográfico del Chocó en las últimas décadas. En ellas predominan las máquinas, no la gente. Estas fotos ilustran, y en esa medida permiten apreciar cómo funcionan esas tecnologías. Los textos son un excelente complemento para entender cómo se usan las bateas, las matracas y las motobombas, y cómo operan las draguetas, las retros, los dragones (como se les dice a las dragas) y los elevadoras.

Aunque tienen la virtud de la sencillez, los textos pecan de simplistas. Los autores evocan un mundo tradicional idílico resquebrajado por el capital (y ensombrecido por el conflicto armado que ha causado tanto dolor en el Chocó desde finales de la década de 1990). Las causas del problema son fundamentalmente externas. Ante este panorama solo queda la alternativa de la resistencia. Aunque no hay duda de que la minería ha generado una catástrofe ambiental, producido tensiones en las comunidades y aumentado su vulnerabilidad, el pasado no era perfecto. La idea de un mundo tradicional impide ver que siempre ha habido cambios. En últimas, esta visión dificulta entender las causas de lo que está sucediendo. Ángela Castillo explica, en el libro que escribió con Sebastián Rubiano titulado La minería de oro en la selva: Territorios, autonomías locales y conflictos en Amazonia y Pacífico, 1975- 2015 (publicado por Ediciones Uniandes en 2019), que, al menos en el San Juan, los dueños de las retroexcavadoras negociaron con la gente local, reconociendo y respetando el derecho minero consuetudinario. Los chocoanos aceptaron a las retros, porque, contrario a lo que afirman los autores, sus beneficios tocan a la mayoría de las personas, aunque sean efímeros y menores que los costos que esta minería genera.

La limitación en la visión que estoy anotando se observa en la insinuación de que los retreros incumplieron al no restaurar. Sin embargo, la misma gente sabía que eso era imposible: había visto lo sucedido en la comunidad vecina y aun así vendió. Cagan y Kelsey, como yo, disfrutan de muchas de las ventajas del capitalismo consumista (como lo es poder visitar el Chocó); los chocoanos también quieren su parte. En fin, el problema es más complicado y no reconocerlo dificulta emprender cualquier acción que resulte efectiva para enmendar los daños y enderezar el rumbo.

El libro da cuenta de una tragedia. Como dicen los autores, después de que pasan las máquinas, los sonidos de la selva desaparecen y en el aire queda una sensación de pérdida, no de bienestar. Me habría gustado saber más de la experiencia de los autores, nuestros guías en este viaje, y también habría agradecido escuchar un poco más las voces locales, especialmente en la parte final de testimonios. A fin de cuentas, es esa riqueza humana la que le da el tono esperanzador al libro. Son loables los esfuerzos de quienes, como el Padre Remo Segalla, han tratado, así sea infructuosamente, de ponerle una talanquera al desastre. Lo mismo es cierto de quienes han apoyado procesos para lograr una minería sostenible o generado ilusiones con la sentencia que hace al río Atrato sujeto de derechos. Cagan y Kelsey utilizan el poder de las imágenes para recordarnos—y hacernos sentir—lo que ha estado sucediendo en el Chocó. Es un logro que hay que aplaudir. Ojalá El precio del oro libro tenga la difusión que merece.

Winter 2021, Volume XX, Number 2

Claudia Leal is a professor at the Department of History and Geography at Universidad de los Andes in Bogotá and author of Landscapes of Freedom, Building a Postemancipation Society in the Rainforests of Western Colombia (The University of Arizona Press, 2018), published in Spanish under the title, Paisajes de libertad: El Pacífico colombiano después de la esclavitud (Ediciones Uniandes, 2020).

Claudia Leal es profesora del Departamento de Historia y Geografía de la Universidad de los Andes en Bogotá y autora de Landscapes of Freedom, Building a Postemancipation Society in the Rainforests of Western Colombia (The University of Arizona Press, 2018), publicado en español con el título, Paisajes de libertad: El Pacífico colombiano después de la esclavitud (Ediciones Uniandes, 2020).

Related Articles

A Review of The Archive and the Aural City: Sound, Knowledge, and the Politics of Listening

Alejandro L. Madrid’s new book challenged me, the former organizer of a musical festival in Mexico, to open my mind and entertain new ways to perceive a world where I once lived. In The Archive and the Aural City: Sound, Knowledge, and the Politics of Listening, he introduced me to networks of Mexico City sound archive creators who connect with each other as well as their counterparts throughout Latin America. For me, Mexico was a wonderland of sound and, while I listened to lots of music during the 18 years I explored the country, there was much I did not hear.

A Review of The Interior: Recentering Brazilian History

The focus of The Interior, an edited collection of articles, is to “recenter Brazilian history,” as editors Frederico Freitas and Jacob Blanc establish in the book’s subtitle. Drawing on the multiplicity of meanings of the term “interior” (and its sometimes extension, sometimes counterpart: sertão) in Brazil over time and across the country’s vast inland spaces, the editors put together a collection of texts that span most regions, representing several types of Brazilian interiors.

A Review of Central America in the Crosshairs of War; on the Road from Vietnam to Iraq

Scott’s Wallace’s Central America in the Crosshairs of War; on the Road from Vietnam to Iraq is really several books at once that cohere into a magnificent whole. It is the evocative, at times nostalgic, at others harrowing, personal account of a young journalist’s coming of age during his first foreign journalism assignment, always keenly observant and thoughtful. But it also offers a carefully developed analysis of the nature of U.S. foreign policy, at least in those poorer parts of the world where it has intervened militarily or more clandestinely, or heavily supported the wars waged by its clients. Wallace has witnessed these wars both earlier and later in his life, as a citizen and journalist.