“Uncontacted” Peruvians

Testing Free, Prior, and Informed Consent

Fall 2014, Volume XIV, Number 1

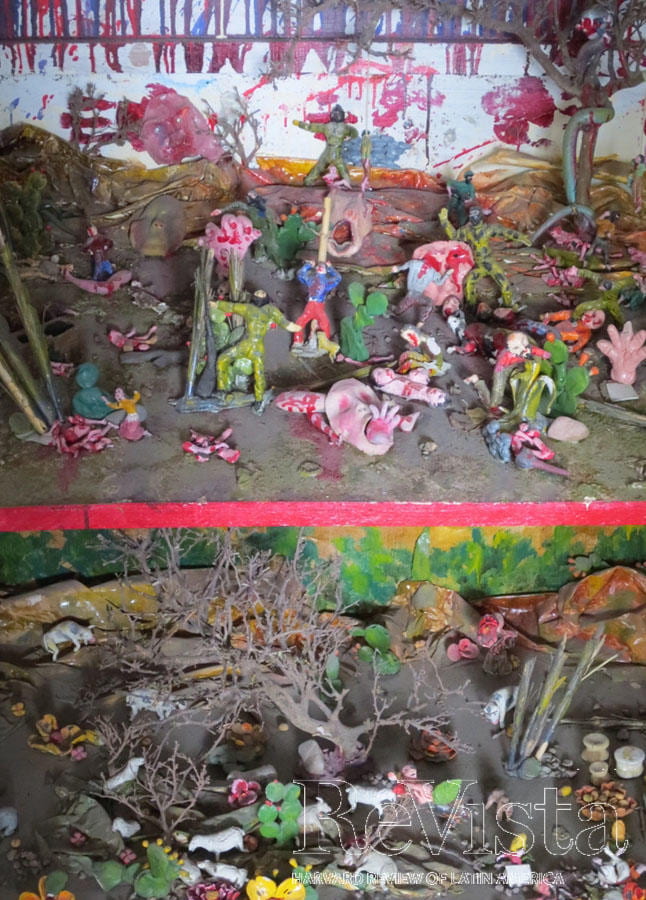

A closeup of a retablo depicting political violence at the Memory Museum in Ayacucho. Photo by June Carolyn Erlick.

In October 1987, the World Wildlife Fund asked me to look into charges that workers in Peru’s Manu National Park were violating the human rights of the resident Machiguenga Indians. The leader of Tayakome, one of the few native villages in the park, had accused a park guard of kidnapping one of the local women. After a 3-day canoe trip up the spectacular Manu River, an ex-park director and I arrived and immediately learned that a young woman was, indeed, missing. But it soon turned out that she, the village leader’s daughter, had simply eloped with her Machiguenga boyfriend. Most of the villagers regarded him as a polite hard-working boy, and defended the marriage. After a public meeting the case pretty much closed itself. However, on the trip, we approached indigenous communities with genuine human rights concerns and precarious lives, currently cast into high relief.

As we camped along the river one night, our Machiguenga bowman began to pace anxiously up and down the beach, listening to sounds on the opposite bank after seeing a footprint in the sand. He was certain that we were being watched by Mashco-Piro, some of the mysterious and, for him, feared “uncontacted” indigenous groups living inside Manu Park. The next day, we docked at the Smithsonian’s Cocha Cashu Biological Station. On the opposite bank sat two women, said to be Mashco-Piro. They visited regularly, waiting, we were told, for food or aluminum cooking pots. We were thus introduced to the extraordinary human diversity of southeastern Peru—the formally recognized “native communities” like Tayakome; groups in “initial contact” seated by the river bank and, literally, on the edge of Western science; and the “uncontacted,” identified largely by mysterious footprints and sounds in the night.

Now, almost thirty years later, these distinct groups continue to complement the area’s extraordinary biodiversity. But now the small dramas of indigenous life are overshadowed by concerns over the expansion of a multinational natural gas project, Camisea. The Machiguenga, fortunately, can now voice their concerns through a regional ethnic federation, FENAMAD. Most of the “initial contacts” are now in closer contact, and demanding basic rights. Some have even traveled to Washington to protest their lack of representation and to register claims for compensation, education and health care with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. They are supported by national and international human rights norms, which now obligate protections that could hardly have been imagined earlier. For those classified as “uncontacted,” currently, most agree that no contact should be made.

Understanding the “Uncontacted”

For some observers, the Mashco-Piro—as well as Ecuador’s Huaorani, Colombia’s Yuri, and similarly isolated peoples in Brazil—provide rare windows into our pristine, environmentally-harmonious, but thoroughly imagined Stone Age past. For others, such groups have simply chosen to live apart. For those seeking access to nearby natural resources, however, they are obstacles. Human rights advocates and other supporters worry that the inexperienced and vulnerable “voluntary isolates” will be harmed as they are suddenly thrust into contact and, most likely, conflict with a more powerful outside world.

History supports concerns and suggests protections. Most of the uncontacted Upper Amazonians share tragic oral histories in which, from about 1879 until 1912, their not-too-distant ancestors were suddenly set upon by rubber gatherers—Peruvians, Brazilians, English and Jamaicans—seeking the world’s only natural sources of latex. The rubber barons frequently captured and, through torture and slavery, put to work the more numerous, more highly organized, and thus more efficiently worked, populations. Smaller groups deeper in the forests like the Mashco-Piro were seen as wild unemployable nuisances. So rubber gatherers simply chased, murdered or massacred them.

The Rubber Boom ended in 1912, with the introduction of more labor-efficient plantations in Asia, leaving the Amazon relatively quiet. However, the earlier violence—inexplicable to the Mashco-Piro—encouraged seclusion in interior forests, where the elders told fearsome stories and advised caution and defense.

Voluntary isolation was not always difficult, nor was it absolute. As late as my trip in 1987, Peru’s main concerns were Sendero Luminoso and, in the Amazon, the related assassination of Asháninka Indians. However, a few missionaries and anthropologists, the regional Indian organization (FENAMAD), and the national organization (AIDESEP) were monitoring the “uncontacted” peoples. FENAMAD officials told of the Mashco-Piro’s sporadic contacts, even simple conversations, with neighboring groups, particularly the Piro, their distant linguistic cousins. So isolation was not complete, but relative. Even then observers had begun to raise concerns for the Mashco-Piro’s health, as contacts and epidemics increased. At that time, such dangers came largely from a few local loggers and artisanal miners who wandered unregulated in the area.

New Rules for Contact

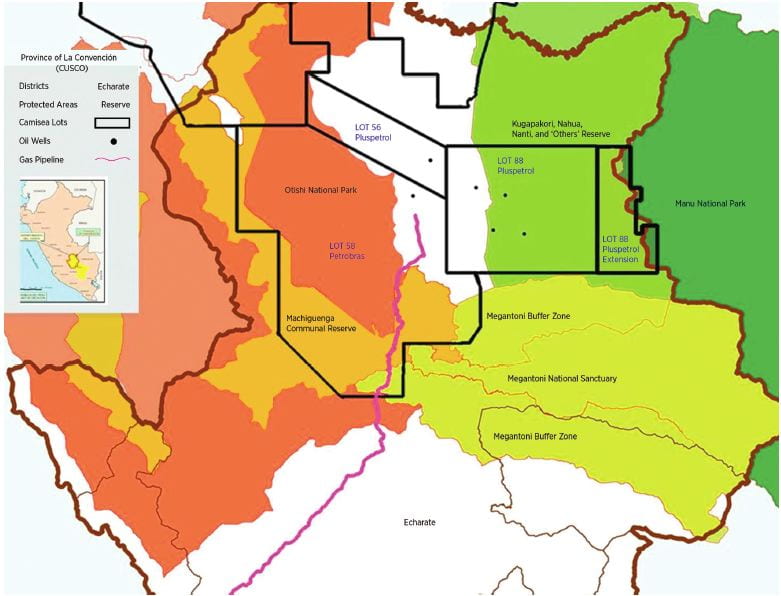

Since then, Peru has recognized the “voluntary isolates’” vulnerability and, in many ways, has excelled in legal protections. South of Manu (declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1990), the government established the adjacent Megantoni National Sanctuary and, to the west, set aside half a million acres as a protectorate for Kugapakori and Nahua people. Then, in 2000, illustrating and accommodating the still-unknown nature and size of uncontacted population there, the government renamed it the “Kugapakori, Nahua, Nanti and ‘Others’” Reserve. In 2006, Peru provided special protections for voluntary isolates through Law 28736, the Law for the Protection of Indigenous Peoples and Originals in Situations of Isolation or Initial Contact.

Over the same period, international indigenous rights standards also developed rapidly. In 1989 the United Nations adopted the International Labor Organization’s Convention Number 169, on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples, ratified by Peru in 1994. In 2007 the United Nations, with Peru’s strong support, passed the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Among many protections, these instruments address conflicts over economic development and natural resources. While communities have no absolute veto over exploitation of subsurface resources (e.g., oil, gas and minerals), the state has a clear duty to consult with them and make sure that development does not harm indigenous peoples or their environment. The state must also provide compensation for resources extracted from indigenous lands or otherwise affecting their lives and livelihoods.

More recently and in response to increasing disputes over the actions of transnational companies, the United Nations has developed a set of standards. Drawing on existing human rights sources, the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights now help to implement the United Nations “Protect, Respect, and Remedy” Framework, developed by the Harvard Kennedy School’s John Ruggie during his terms as the UN Secretary General’s Special Representative for Business and Human Rights. States and companies now have basic guidelines for linking development to human rights.

Peru’s indigenous peoples and their communities should no longer be passive victims of development and, beyond basic protections, they are also recognized as active participants in its planning and implementation. Drawing on the language and spirit of ILO Convention No. 169 and the UN Declaration on Indigenous Peoples, in 2011 Peru passed the Law of Prior Consultation, thus acknowledging a critical means toward the foundational human right to self-determination—consultations with the objective of free, prior, and informed consent. Peruvian indigenous peoples now have the right not simply to know what will happen to them and their lands, but also to discuss, disagree and otherwise negotiate such development.

Despite this promising legislation, the specific means for consultation—the how, when, and with whom— are still being developed and are not entirely clear in Peru and other Latin American countries. Part of the problem is that the rules and procedures for defining an “appropriate” consultation must also be determined in an inclusive and participatory manner. Government officials must cede their perceived full authority in such matters, and many are hesitant to do so. Anger over the Peruvian government’s unwillingness to consult properly with communities and organizations led to tragic violence in Bagua, another oil development area, in June 2009. Peru remains keenly aware of the obligation to consult and understands that local sensibilities are frequently frustrated, if the government fails to do so. However, with regard to “voluntary isolates” and considering the obligation not to contact them, Peru has delegated authority to the Ministry of Culture. So expansion of the Camisea gas fields is a critical test of indigenous rights as well as a vital lubricant to Peru’s economy. Indigenous rights to both protection and consultation will be tested.

The Camisea Project

Shell Oil began exploration in Camisea in the 1980s, quickly facing local protest as access roads opened entry for loggers and colonists into previously-isolated indigenous communities. However, by the mid-1990s, Shell sought to showcase Camisea. While working to minimize deforestation and road construction, directors and community relations workers also won local, national and international praise for their support of health, education and other grassroots development projects, undertaken with extensive consultation and participation. By contrast, other international oil companies exploring in adjacent areas populated by “uncontacted” were heavily criticized.

Shell, for reasons unrelated to social or environmental issues, left Camisea (Block 88) in 2000, and was replaced by a consortium led by Argentina’s Pluspetrol, which began gas production in 2004. The new operators still work to maintain high environmental standards and to avoid contact with indigenous communities. Recently, however, Pluspetrol and the Peruvian government decided to expand exploration within Block 88. More than 70 percent of that block overlaps with the Kugapakori, Nahua, Nanti and “Others” Reserve. Expansion will require many miles of seismic studies (i.e., subsurface profiles created by monitoring reverberations from subterranean dynamite explosions), 18 new wells, and a pipeline to connect the wells to existing facilities. Given Peru’s progressive national and international legislation, it would appear that sufficient environmental and social protections are in place, and that the overlap between hydrocarbon development and indigenous reserves is simply a matter of recognizing existing rights and negotiating appropriate plans. However, the will of the Peruvian government and the intentions of the company have been questioned.

To illustrate, the Environmental Impact Analysis, a green light of sorts for the expansion, was approved in late January 2014. The report required a technical opinion on the risks involved for the groups. Prepared by the Vice Ministry of Intercultural Affairs, the report, presented in July 2013, included 83 points and expressed serious concerns for the voluntary isolated. The Ministry of Energy and Mines questioned the report, which was subsequently replaced by a significantly shorter list (37 points), expressing less concern. The Vice Minister for Intercultural Affairs has since resigned. The Ministry of Energy and Mines argues that the earlier report drew on incomplete information and that all important concerns have now been addressed. Not surprisingly, suspicions remain and the Camisea expansion has attracted considerable national and international attention.

Responding to the crisis in late March 2014, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, James Anaya, submitted a report on his December 2013 visit to the area. Acknowledging many of the positive efforts made by the government and Pluspetrol, he nonetheless emphasized the scarcity of basic data on the current situation of the uncontacted, thus asking how the Ministry could claim adequate mitigation of physical and environmental risks, contingency plans and means for compensation. While questioning the apocalyptic predictions of some national and international NGOs, the report nonetheless noted that other members of civil society had presented legitimate questions that should be answered. In addition, the national indigenous organization, AIDESEP, had proposed its own participation in the data gathering and subsequent monitoring of progress, and the report supported that participation. Increased participation of this sort would significantly enhance transparency.

The report also noted that there had been no consultation with the affected communities that are in initial contact with the outside world (as opposed to those that are still uncontacted), despite the Peruvian government’s formal acceptance of the right to consultation. The Special Rapporteur recommended consultations with these communities prior to implementation of the expansion project. This suggests that the current blanket prohibition against any sort of contact with “voluntary isolates” must be reconsidered as more “uncontacted” move to “initial contacts.”

Additionally, the ongoing gas development and the phased expansion, for which problems are certain to arise regularly, the Special Rapporteur recommended a working group (mesa de diálogo) that includes representatives from civil society, government agencies and Pluspetrol, as well as indigenous communities and organizations. However cumbersome, such a forum provides permanent monitoring.

The Ministry of Energy and Mines has argued that consultation is not required because the overall Camisea project was approved prior to the passage of the Law of Consultation and the establishment of the Kuagapoaki, Nahua, Nanti and “Others” Reserve. This legal-procedural argument, however, goes against the very spirit of the reserve, which was established solely to protect voluntarily isolated peoples. The response also flies in the face of Peru’s extensive record of support for international norms, and creation of national ones, that guarantee broad indigenous rights, including consultation. So, it’s not simply a matter of which particular law takes precedent, but a broader question of compliance with a set of established agreements and commitments to provide security for citizens. Peru now has an obligation to fully document the potential impact of expanded natural gas development and then to present the results for discussion in the public sphere. Until then, the project, however well-designed otherwise, does not meet Peru’s own standards, and the Rapporteur recommended that expansion not move ahead until consultations occur and outstanding concerns are addressed over the potential impacts of the expansion.

The importance, indeed power, of this argument extends well beyond an isolated section of rain forest. In Peru and many other countries, development schemes often overlap with indigenous territories. With the new international standards for business and human rights, Peru’s perception of its “right to development” no longer needs to be seen as in conflict with the human rights of the indigenous residents. In the past, utilitarian logic and arguments would have asked whether Peru should benefit the many by providing them with abundant inexpensive natural gas, or protect the lives and habitat of a few hundred native people. Such utilitarian debates are no longer appropriate in situations like Block 88. Peru, of course, has the right, indeed obligation, to develop its economy. Peru has also adopted international agreements, created national laws, established norms and limits, and created expectations for and with regard to indigenous peoples. It is no longer a question of either rights or development, but one of accommodating mutual obligations within existing standards.

Likewise, as illustrated by the transition of some communities from “uncontacted” to “intial contacts,” indigenous peoples are not static societies, frozen in time. So some current human rights procedures have to be reconsidered. While groups like the Mashco-Piro certainly have a right to peace and privacy, should that prevent the State from guaranteeing their basic right to health care? Or preclude consultation? Relative isolation makes such groups extraordinarily vulnerable to introduced disease. Horrible polio epidemics hit Ecuador’s Huaorani in the late 1960s, while upper respiratory illness killed many Mashco-Piro later. To leave such groups unprotected and unvaccinated, when it’s possible to protect, is certainly in violation of the most basic understanding of the Right to Health. Precautionary methods and sanitary approaches must, of course, be developed but that’s not hard for skilled public health workers. And it’s also quite certain the local indigenous federations can figure a way to “get in” to communities with such help sensitively and safely, and even develop ways to dialogue and consult.

For their part, many of Peru’s indigenous communities and organizations now accept these challenges. Leaders of AIDESEP recently stated “…in matters of hydrocarbon development, we have moved from protest to proposal.” Now they need to talk, regularly. Dialogue may not eliminate disgruntled Machiguenga fathers or fears of Mashco-Piro in the dark, but consultation can go a long way towards reasonable means for approaching change and development, while protecting fragile lives.

Ted Macdonald is a Lecturer in Social Studies at Harvard University. He has served as Projects Director for the human rights NGO Cultural Survival and then Associate Director of the Program on Nonviolent Sanctions and Cultural Survival at Harvard’s Weatherhead Center for International Affairs. He co-edited, with David Maybury-Lewis, Manifest Destinies and Indigenous Peoples (Harvard University Press, 2009). He thanks James Anaya for his excellent comments and essential clarifications, but assumes responsibility for all opinions expressed here.

Related Articles

The Violence of the VIP Boxes

English + Español

In Peru, the upper class does not like to mix with those they consider different or inferior. Their maids on the beaches south of Lima are not allowed to swim in club pools and, sometimes, not even in the ocean. The VIP boxes at sports and theater events maintained by the government are a public display of a private practice that reproduces in the public sphere the worst aspect of private hierarchical structuring.

Peace and Reconciliation

English + Español

Eleven years have gone by since the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission presented its final report. The report reconstructed the history of many cases of massacres, tortures, murders and other serious crimes. At the same time, it contributed an interpretation of the…

I Ask for Justice: Maya Women, Dictators, and Crime in Guatemala, 1898–1944

On May 10, 2013, General Efraín Ríos Montt sat before a packed courtroom in Guatemala City listening to a three-judge panel convict him of genocide and crimes against humanity. The conviction, which mandated an 80-year prison sentence for the octogenarian, followed five weeks of hearings that included testimony by more than 90 survivors from the Ixil region of the department of El Quiché, experts from a range of academic fields, and military officials.