The Mexican Angels in the Attic

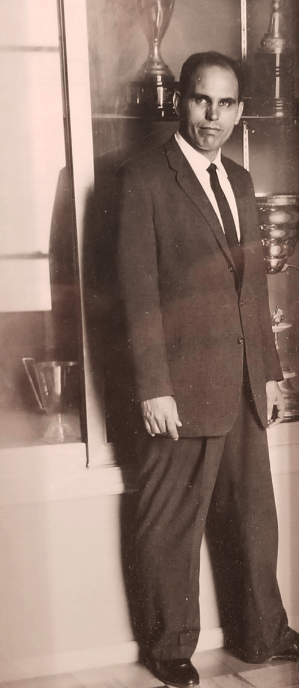

Years before I met the Mexican angels in that Chicago attic, my abuela Carlota Carranza Carrasco told me about religion. Carlota was born in Batopilas at the bottom of the Cañon del Cobre in 1896 and crossed the border into El Paso to escape the chaos of the Mexican Revolution in 1912. She met Miguel Carrasco in a small Protestant church in the Segundo Barrio, married and had three boys, Miguel, Eliseo and my father David. Carlota was beloved by the extended family on both sides of the border and we grandchildren loved spending time with her. She had wisdom, a sense of humor and beautiful brown skin. Once I asked her how she kept her skin so beautiful and she said, “I have a secret ingredient. Do you want to know what it is?” Fascinated, we gathered near to hear what her secret was. “My secret ingredient is” and she hesitated with a twinkle in her eye, “prayer, prayer, prayer and…..good cosmetics!”

My father taught me how to pray in the balcony at Marvin Memorial Methodist Church in Four Corners, Maryland. He had timed our arrival to sit in the balcony at the rear of the church just after the service started. From there, I could see religion in action—a devout community; prayers, silent and spoken; enigmatic stories recited from a sacred book; enthusiastic singing by a swaying choir; eloquent, inspired spoken words; collection plates passing through a murmuring congregation as coins and bills dropped in. Underneath it all was a quest for the healing of bodies, hearts and souls.

When the order of service called for silent prayers I often sneaked a peek at my father, sensing an intense, strange mood emanate from his body as he began to breathe more deeply.

After the service another meaning of religion closer to the cosmetics of my grandmother appeared—hero worship. One line of worshipers always shook hands with the pastor at the door on the way out of the church. Another line of men always gathered around my 6 foot 4 inch Mexican American father, outside on the lawn, to praise him and hear his views on his state championship basketball team’s latest victory the night before.

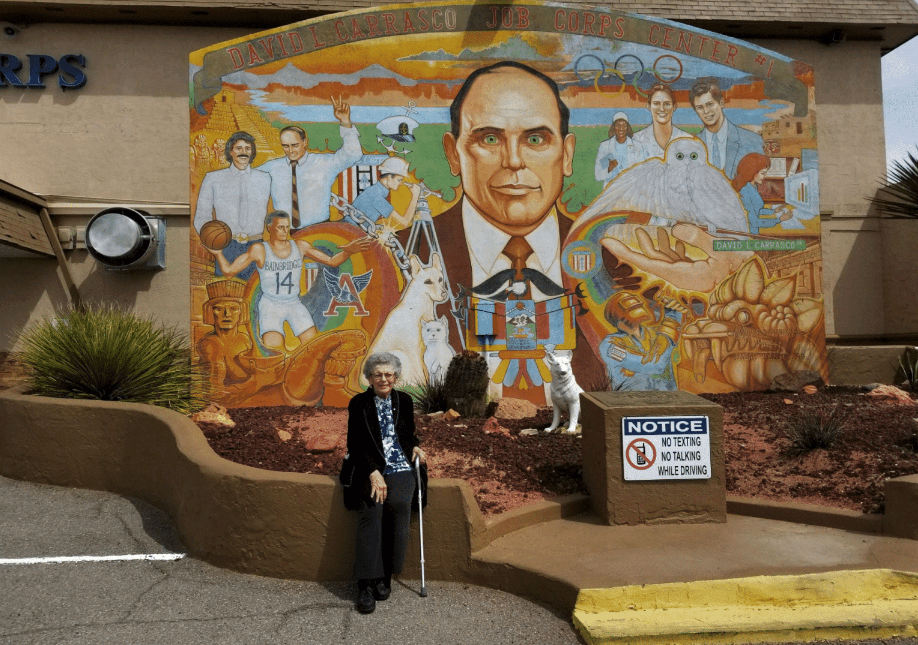

Mural in honor of David L. Carrasco at the David L. Carrasco Job Corps Center in El Paso, Texas. His 96-year-old widow sits in front.

“I took my grandmother’s words and my father’s example with me to the University of Chicago Divinity School. There, I encountered a new academic discipline religionswissenschaft— the scientific study of religions—filled with other words and examples.

“That course, ‘Introduction to the History of Religion,’ goes all the way back to the bones” said the dean of the Divinity School. I was hooked by “bones.” I dragged myself across Hyde Park and into Swift Hall at 8:30 a.m., always sitting in the back row with minority students. We never said in 1968 why we sat in the back—it was a form of symbolic protection in a racist world.

Alfred Jensen’s Myth and Cult Among Primitive Peoples led me on a new path of understanding religion and spirituality, the subject of this issue of ReVista, the Harvard Review of Latin America. His three themes captivated me: ergriffenheit— seized with emotion; Master of the Animals; and Tricksters. Ancient hunters were seized by “deep emotions” tinged with numinous power during the hunt and kill of animals. Through prayer and negotiation, hunters sought to curry favor with the great spirit animal or “Master of the Animals,” who guarded and dispensed the creatures in the forest to hunters who showed respect, skill and courage. Then there were tricksters: trickster tales from Native America, Africa and elsewhere told of a rebel figure, part thief, part clown who challenged the High God or other authorities and became a culture hero even when caught in the act of rebellion. Stories my father told me about a Chicano trickster in El Paso and Ciudad Juárez came back to me. I wrote out the stories of two-named “El Tortolo/Dusty Hobo” for my professor. News of my trickster cycle passed through the faculty and I became valued as akin to a primary source about the history of religions in the Mexico/U.S. borderlands.

The hero of the Divinity School was best-selling historian of religions and novelist Mircea Eliade who had created a new language for understanding religion and spirituality through a broad study of religions of the world. Eliade’s original words and phrases such as “hierophany,” “homo religious,” “axis mundi,” “myth of eternal return,” “in illo tempore,” and “regeneration of time’” illuminated stories, rituals and sacred places in nature and society. He and African American scholar Charles H. Long taught us the radical position that “the sacred is an element in the structure of consciousness and not a moment in the history of consciousness.” Religion is more than ideas about God, sacred books, buildings and theology. It is also about numinous experiences, ancestral wisdom, the ineffable the presence of the divine.

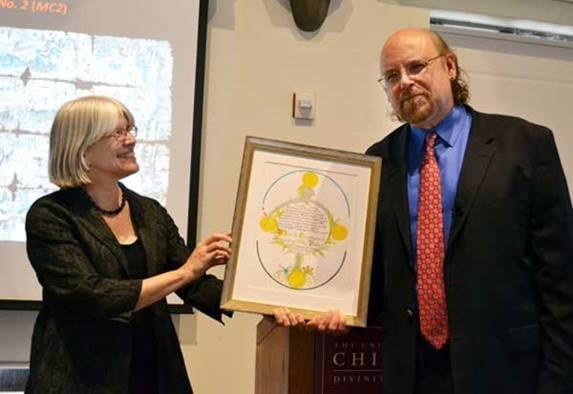

Charles Long, one of Carrasco’s mentors. Taken by Lawrence Desmond and published in Scholars in Dark Glasses: Photos of MMARP Symposia, 1982 to 1994.

That all brings me back to Carlota’s cosmetics. Carlota, a devout woman who lived by the Bible, quoted its stories of miracles, obedience, love and renewal in words and letters she wrote to me over the years. Studying the origins of cities and the symbolic design of capitals with the great urban ecologist Paul Wheatley at Chicago, I slowly realized that her word was a cypher for cosmology and the ritual ways humans adorn and redesign their lives, ceremonial places, names and destinies based on cosmo-magical experiences.

Aztec Sun Stone whose organization mirrored the layout of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan.” Drawing by David Stuart, The Mesoamerica Center, The University of Texas at Austin.

This lesson was later expanded through learning with Latin American historian William B. Taylor that in colonial New Spain altars, shrines, and great cathedrals were valued, literally, as vessels of sacred treasure and places “of refuge, meant to welcome, honor, protect and contain the divine presence that had shown favor there and might do it again as a ‘theatre of a thousand wonders’” (William B. Taylor, A Theater of a Thousand Wonders: A History of Miraculous Images and Shrines in New Spain, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, p.1). In memory of my Mexican ancestors and through the teachings of Charles Long on religions of the oppressed I came to understand that this meaning of cosmetics also called for changing the face of our racist society by developing new narratives, rituals, art and movements for freedom.

I also had a nighttime life in the Mexican barrio, Pilsen or “18th Street,” as we called it. Fiestas, bars, gang meetings, community organizing and things unspoken. The Chicano movement was going strong, and I enthusiastically taught a course on Mexican and Chicano history and religions for barrio residents at the Centro de la Causa. Porfirio Torres, an undocumented visitor to the course, invited me to lunch at the Tlaquepaque restaurant and said, “I want you to come meet a Mexican angel who does beautiful things with spirits every Thursday night. Come over to the attic in Little Village.” The angel’s name was Niño Fidencio Constantino.

The Night Battle with Niño Fidencio

When I met Torres on a street corner in Little Village around twilight, he told me, “When we are in the presence of the angel, you must not cross your arms or legs because that will block the flow of spiritual energy.”

“I understand,” I said.

“One other thing. If he asks you, ‘Cuando se muere?’ you must answer, “Cuando Dios y usted quieran.”

The mention of death in his statement rattled me and I said, “Hold on, Porfirio, is this going to be dangerous for me?”

“You have nothing to fear if you follow these instructions.”

But fear grew in me as we walked off to a side street, around the back of a three-story row house and up the outdoor stairs to an attic room. Once inside we joined two dozen Mexicans who were quietly waiting for El Santo Niño Fidencio Constantino to appear and carry out healings. I was to come back to the attic shrine every Thursday night for two years and I will never forget that first evening.

Niño Fidencio touched me softly on the shoulder as I faced him and the altar with colorful Christmas lights twinkling off the statues of Mexican saints including mine, Santo Judas. . A dark spirit had come to dwell in one of my shoulders causing me constant pain. He held my wrists and felt my pulse with his two thumbs while we gazed at each other. He was nearly a foot shorter than me and as I looked down at him his eyes were almost completely rolled up beneath his eyelids, so the whites of his eyes were evident. He hummed softly and with a slight smile. Soon his head began to bob, and he said, “Padrinito David, you are the smallest of all my followers, and I will make you taller so the dark spirit within you can find a way out.” He had me turn my back to him and he turned his back to me. He reached his arms back and locked them into mine and in a swift motion bent me backward in a curve over his back and shoulders. He began to bounce me on his back saying several times, “Padrinito David, don’t worry—you won’t fall, you won’t fall because you are the smallest of all my devotees.”

My head was now upside down and my eyes were gazing at the colorful altar with its tiny samurai sword and image of Santa Claus. I felt my spine stretching, my feet dangling off the floor and feared I would slip off his back—in one direction or the other but he clasped me tight. I heard gentle laughter coming from the others in the attic room. “Padrinito David, prepárate para aterrizar”—prepare to land— and with one more bounce stood up straight and tossed me back onto my feet. He turned me to face him again, smiling at me. He took some stems with green leaves and began to brush me front and back while saying a prayer. I felt that the dark spirit in my shoulder was gone.

During a later séance he led us into a ferocious battle between spiritual danger and fire. After surveying the room with his rolled-up eyes, he announced to the group of Mexicans in the room. “There is someone here with a danger in her heart. Another more powerful spirit will soon come to do battle.” I saw people’s bodies stiffen a bit at this announcement. During earlier healing ceremonies I had witnessed two other spirits enter the materia’s body and carry out rituals to heal people. By this time I had become familiar with the vocabulary, which added to the emotional impact of the experience. Materia or caja , I learned, is the name of the material person into whom the Niño Fidencio and other spirits descend in a epileptic-like seizure.

I became familiar with the spirits too. One spirit was that of the famous south Texas curandero and clairvoyant Pedro Jaramillo who died in 1907. When his spirit entered the “materia,” his body took on the shape of an older, more muscular man and his healing gestures were forceful, sometimes leaving a soreness in my arms and shoulders. The other spirit who had visited the group was an “angel-child” known as “Miguelito” who healed while the “materia” was perched on the shoulders of two men carrying him around the room.

Niño Fidencio completed a healing ritual with a man and turned and knelt before the altar and we all got down on our knees and began to recite the Ave Maria prayer in Spanish. That attic space had no windows or fan and a heavy stupor filled the room as the minutes passed and we prayed. Suddenly a loud piercing cry broke out of Niño Fidencio’s throat and he began to shudder and jerk and moan as though seized by an epileptic fit. Our praying stopped and we watched as the convulsions slowly subsided. Tension filled the room. What came next was a revelation to me. The materia got up from his knees and turned to face us and I was astonished at how physically different and younger the he now looked. He was square-shouldered and with his eyes rolled up in his head, so we could see mainly the whites of his eyes, he began to speak a language I had never heard. It seemed a mixture of Spanish and an indigenous dialect and he struggled to get some words out as though there was a disconnect between his mind and his voice. His assistant, a woman who always accompanied the materia when in a trance, translated to us in Spanish what this new presence was saying. “This is the Pluma Roja” she said, and he has come to confront the dark spirit that threatens the life of one of you. Pluma Roja has descended from the house of light as a messenger of God to fight with a dark spirit that is here.

Using gestures and grabbing each of us by the shoulders or arms he moved twelve of us into a semi-circle and had us hold hands and made the people on each end of the semi-circle touch the wall. He told the others behind us to leave the room and close the door. He had transformed our remaining group into a protective wall, a magic semi-circle closing out all that was behind us so that a dramatic healing could take place in the space before us. He approached a woman in the semicircle, stood before her for a long minute and placed his hand over her heart. Soon he began to shake his head up and down. He took her wrist forcefully and led her forward in front of the group facing the altar. In his trance state he went over to the altar taking a bottle filled with a liquid and poured it onto the floor in front of the woman, in the shape of a cross or x. Then he took two eggs, broke them onto the liquid cross. He then had the assistant take a pan from the altar and poured chilis onto it. Then he lit a match and threw it onto the floor. A flame shot up as the liquid and eggs began to burn. I felt the semi-circle drop back half a step—in fear and the woman standing next to the fire on the floor leaned away. Smoke began to rise. Turning to the group, he called in his hybrid language for someone with a strong heart to assist in this battle. He walked slowly in front of us with his rolled-up eyes gazing at us or into us and he stopped in front of me. He put his hand over my heart and looked into my eyes with his and a soft shudder moved up my spine. After a moment he gave me a short punch in the chest, smiled and I heard the words “corazón fuerte,” as he slowly shook his head in a yes gesture. He grabbed me by the wrist and jerked me closer to the fire and the woman. He had me lock my right elbow with her left elbow and began to recite a prayer as the chili smoke began to fill the room. He took the two of us closer to the fire and with gestures and word sounds told us to jump over the fire in the four directions.

By now the fire had settled to about 10 inches above the floor and the woman and I tried to synchronize our jumps over the fire-first straight ahead, then turning around we jumped back in the opposite direction. I could feel the fire’s heat rise against my legs as we awkwardly jumped over the fire.

Then the Pluma Roja put me back into the semicircle and forcefully took the woman by the shoulders and began to rapidly wave flowers and an egg over her body. The pan was put over the fire once again and more smoke rose into the air and began to hit the ceiling and curl back down toward our heads. Eyes began to water, and a burning sensation rose in my nose and throat. He began to recite a prayer in his sacred language and at first, I could not make it out. Then I heard bits of lines, “doce apóstoles…diez mandamientos…ocho angustias” and it came to me, he’s reciting the “Doce Verdades del Mundo”— the twelve God-given truths— but in reverse. I heard “cuatro santos” and remembered that in Chicano culture and in the borderlands, this prayer was sometimes used in extreme circumstances to battle the presence of a witch or evil force threatening a person or family. As the smoke intensified and the room became hazy, I saw that the Pluma Roja had a long cord and began to tie one knot after another as he recited the prayer. The people in the half circle magical wall began to breathe heavily and ask to be let loose. People began to cough, and some started to bend over searching for fresher air beneath the enveloping smoke. The burning in my nose and throat forced me let go of the hand of my neighbor and to pull up my shirt to cover my nose and mouth to filter the burning smoke. I squinted my eyes as the haze intensified and someone pleaded, “Por favor el humo está lastimándonos. Déjanos salir.”—”Please, the smoke is hurting us. Allow us to leave.” But the Pluma Roja who showed no difficulty breathing continued with his prayer. Now the burning in our noses, throats and lungs was intense and each of us dropped to the floor, crawled to a corner and gasped for air. Down on the floor with my mouth pressed to a spot where the wall and floor joined, wheezing and shielding my eyes, I glimpsed the Pluma Roja roughly massaging the woman. The back door opened, and people rushed from the room and I followed. The two windows in the outer room were thrown open and several stuck their heads out into the night. As I recovered my breathing I looked back into the room and saw the Pluma Roja now alone, kneeling in front of the altar. Through the dissipating haze I squinted and saw the miracle. He was quietly reciting a prayer that droned on for a minute or so but he had no trouble breathing in the same burning atmosphere that had driven the rest of us gasping and pleading out of the room. Then his body began to shake and jerk and soon we all heard the piercing cry that shattered the silence as the spirit of the Pluma Roja left his body. His jerks and shakes slowed down and then he began to cough and struggle to breath, like the rest of us. Through my watering eyes I saw him rise from his knees and rush from the room back into his fully human state to be greeted and thanked by all of us.

Through that intense experience with the spirits and the equally intense intellectual discoveries at the University of Chicago Divinity School, I came to know the sacred ingredients of religion—recognizing signs of divine presence, devotion to the Other and the ritual cosmetics we use to redesign our lives, valued places and relationships.

In this issue of ReVista, you will find authors—practitioners and scholars—weaving those elements into the tapestry of their religious and spiritual lives. These are their ascents, descents, places, memories and revelations.

Winter 2021, Volume XX, Number 2

David Carrasco is a historian of religions working on the sacred ceremonial centers of pre-Hispanic Mexico and the cultural improvisations of the Mexico/U.S. Borderlands. He is the Neil L. Rudenstine Professor of the Study of Latin America at Harvard, with a joint appointment with the Harvard Divinity School and the Department of Anthropology in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. He is the recipient of the Mexican Order of the Aztec Eagle.

Related Articles

Indigenous Peoples, Active Agents

Recently, the Amazon and its indigenous residents have become hot issues, metaphorically as well as climatically. News stories around the world have documented raging and relatively…

Beyond the Sociology Books

If you are not from Colombia and hoping to understand the South American nation of 50 million souls, you might tend to focus on “Colombia the terrible”—narcotics and decades of socio-political violence…

Exodus Testimonios

The audience at Iglesia Monte de Sion was ecstatic as believers lined up to share their testimonials. “God delivered us from Egypt and brought us to the Promised Land,” said José as he shared his testimonio with the small Latinx Pentecostal church in central California…