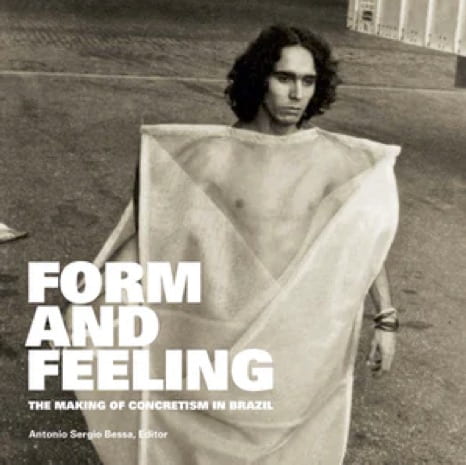

Form and Feeling: The Making of Concretism in Brazil

Form and Feeling: The Making of Concretism in Brazil, edited by Antonio Sergio Bessa (Fordham University Press, 2021)

In Form and Feeling: The Making of Concretism in Brazil, curator Antonio Sergio Bessa gathers together fourteen essays that provocatively reframe canonical practices of art and poetry in 21st-century Brazil. The book’s title reveals Bessa’s interest in complicating narratives of formal innovation alone (form), to address the centrality of psychological and perceptual experience (feeling) for Brazilian artists, poets, critics and pedagogues of the 20th century.

Form and Feeling is the culmination of a 2016 conference held at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York (CUNY), which brought together art historians, curators, and literary theorists from Brazil, the United States and Europe to discuss Brazilian Concretism in art and poetry. The resulting essays are relatively short and well written, making them appropriate for upper-level undergraduates as well as graduate students, scholars of art and literature, curators, artists and general-interest readers. Though a handful of the essays would be challenging without prior knowledge on the part of the reader, most offer erudite yet accessible entry-points into fascinating aspects of modern art and poetry in Brazil.

Many recent scholarly and museological efforts to “globalize” modern and contemporary art history have centered on Brazilian Neoconcretism. Neoconcretism emerged around 1959 in response to Brazilian Concretism. Concretism consisted of hard-edged geometric abstraction in painting and sculpture based on the Art Concret movement of interwar and postwar Europe. In contrast, Neoconcrete works were often immersive or tactile: poetry composed of words and objects to be manipulated, painted planes of color surrounding viewers, space sculpted in the interstices formed by cut metal planes.

In writings by scholars such as Paulo Herkenhoff, Monica Amor, Sérgio B. Martins, and Irene V. Small, this formal and conceptual passage — from Concretism’s rational, geometric forms to Neoconcretism’s perceptual and phenomenological play — has served as a key alternative to normative Euro-American artistic chronologies that hinge on Minimalism. Moreover, well-known artistic innovations of Brazilian artists involved with, or influenced by, Neoconcretism — e.g., Hélio Oiticica and Lygia Clark — have been taken as paradigmatic for global contemporary art practices concerned with liberatory embodiment, the dystopian afterlife of modernist forms, and unequal social relations.

How, though, can we “globalize” the field of modern and contemporary art while still maintaining the specificity of local aesthetic and political projects? Bessa’s introductory text, and his selection and organization of the essays foreground three provocative approaches to this historiographical challenge.

First, Bessa’s framing questions seize upon the prominence of Brazilian Concretism (and, by extension, Neoconcretism) for newly “global” accounts of modern and contemporary art, but seek to undermine fixed ideas about these terms. This misleadingly subtitled book ranges far beyond the idea of Concretism as a historically-rooted stylistic category, demonstrating the elasticity of the concept across visual art, poetry, architecture and pedagogy in Brazil.

Second, Bessa rejects historical narratives of heroic avant-gardes, aesthetic progress and belatedness. Instead, he introduces Stanford poetry critic Marjorie Perloff’s idea of Brazilian Concretism as an aesthetic arrière-garde, “the troops that in battles finish the job initiated by the frontlines” (Bessa 3). For Bessa, Concretism is a useful concept because it epitomizes an aesthetic project centered less on formal feints than on the institutionalization of pedagogical experimentation and the “aspiration to form new individuals through education reform” (Bessa 4).

Third, Bessa makes poetry a central focus for Brazilian artistic debates across various media. Form and Feeling thus revises conventional chronologies of European Art Concret —> Brazilian Concretism —> Neoconcretism, by foregrounding the mid-20th-century “rediscovery” of late-19th century Brazilian poet Joaquim Sousândrade. “While it may seem harsh to suggest that Brazil did not have a visual arts tradition strong enough to account for the constructivist imputes of the 1950s,” Bessa polemically claims, “it is undeniable that our experimental tradition is rooted in literature” (Bessa 7). By drawing a through line from Sousândrade through Concrete poet Haroldo de Campo to sometime-Neoconcrete artist Hélio Oiticica (Bessa 7), Bessa re-centers the history of Brazilian Concretism on writing rather than the visual arts.

The book is divided into three sections, corresponding to new aesthetic forms and institutional structures of the 1930s-1960s; Brazilian counterculture and the experimentation of individual artists during the 1960s and 1970s, and the relevance of 19th-century Brazilian poet Joaquim de Sousândrade for Brazilian poets and visual artists of the 1950s onward.

The book’s first section is organized roughly chronologically, beginning with University of São Paulo architectural historian José T. Lira’s account of 1930s-50s works by civil engineer, amateur architect and performative provocateur Flávio de Carvalho. This text is a bit of an outlier, since Carvalho was neither Concrete nor constructivist, and his importance for Concretism lies in his social role as an avant-garde predecessor rather than in any formal or conceptual continuities. Lira’s interpretation of Carvalho’s works is also overly optimistic about the possibility for mechanization to usher in emancipatory forms of modern embodiment. Still, given the rarity of English-language accounts of Carvalho’s work, Lira’s survey is much appreciated, and his analysis of Carvalho’s Freudianism establishes a precedent for later Brazilian artists’ turns to psychoanalysis.

Beginning the discussion of Concretism proper, University of the Arts London art historian Michael Asbury explores divergent accounts of self-taught Brazilian painter Alfredo Volpi. Focusing on Volpi’s paintings of triangular bandeiras [pennants]—which hover between figuration, Concretist abstraction and Neoconcretist color—Asbury analyzes Brazilian and international understandings of aesthetic empiricism and psychological interiority as a way of revising the critical history of Brazilian Concretism.

Subsequently, CUNY art historian Luisa Valle’s essay takes a single sculpture by artist Mary Vieira, Polyvolume: Meeting Point (1969-70; commissioned 1960), as a focal point for exploring the relationship between Concretism, modernist architecture, and artistic patronage in Brazil, particularly in Brasília.

Three additional essays in this section examine pedagogical developments. UT Austin art historian Adele Nelson’s essay (previously published in ARTMargins) meticulously explores the legacy of Bauhaus educational frameworks for Brazilian art, with particular attention to the early-1950s Institute of Contemporary Art (IAC) at the São Paulo Museum of Art (MASP).

In an essay on the Hochschule für Gestaltung at Ulm, Germany, the Ulm Polytechnic design historian Martin Mäntele analyzes the school’s foundational design courses. Numerous Brazilian artists and designers attended the school during its brief lifespan (1953-1968), and it served as a model for curriculum at the Rio de Janeiro design school ESDI, established in 1963.

Claudia Saldanha, director of the Rio de Janeiro art space Paço Imperial, discusses architect Lina Bo Bardi’s little-known 1965-66 proposals for the architectural spaces and program of the Parque Lage school of visual arts in Rio de Janeiro. Though Saldanha’s essay is geared towards readers already familiar with Bo Bardi’s work, the essay convincingly positions Bardi’s designs for Parque Lage as a transitional project between her early-1960s museums in preserved colonial buildings in Salvador da Bahia and her late-1970s designs for the SESC Pompeia community center in São Paulo.

Section II marks the shift from the 1960s to the 1970s and beyond in terms of Brazilian counterculture, the transition to Neoconcretism and the growing centrality of embodiment for Brazilian artists. Frederico Coelho, a theorist of literature and performance at the Pontifícia Universidade Católica-Rio, sets the scene by exploring the “Tropicalist moment” as a project rooted in youth culture and music, but encompassing the work of visual artists and poets as well. Coelho’s essay succinctly captures the tension of Bessa’s book title by laying out a contrast of rationalist Concretist form versus Neoconcretist feeling, a dichotomy that many of the book’s other texts complicate.

The importance of this turn to perceptual and phenomenological “feeling” come to the fore in CUNY art historian Claudia Calirman’s essay (previously published in Woman’s Art Journal), which discusses visceral explorations of female embodiment in 1970s-90s works by Lygia Pape and Anna Maria Maiolino.

The essay by Antonio Sergio Bessa, a curator at the Bronx Museum of Art, exemplifies this volume’s shift in emphasis from the visual to the verbal, while still maintaining the centrality of embodied experience. Bessa’s essay (previously published in the catalog for Lygia Clark’s 2014 MoMA exhibition), discusses the text of Lygia Clark’s chapbook Meu rio doce [My Sweet River] (composed early 1970s, printed 1984), a textual exploration of psychoanalytic approaches to creativity and embodiment centered on a “primeval” body. Here, “feeling” is not simply a symptom of Concretist-Neoconcretist polarization, but offers a return to the looping, fantastical literature of Brazilian modernists, e.g., Mario de Andrade’s novel Macunaíma (1928), and a confirmation of psychoanalysis’ importance for Brazilian art.

Subsequently, Rio Museum of Modern Art curator Fernanda Lopes’ essay on artist Emil Forman introduces this nearly unknown artist’s 1970s conceptualist works, such as an extensive installation of objects belonging to his family’s recently deceased housekeeper. Lopes shows how Forman’s works participated in Brazilian artists’ consideration of “the massification of the individual through popular culture” (Lopes 167). However, she does not consider the works’ relationship to the administrative aesthetic of contemporaneous non-Brazilian artists such as Marcel Broodthaers Département des Aigles (1972), nor the social class implications of an artwork centered on the personal ephemera of an artist’s domestic servant.

Readers may wish to begin reading this book with the final essay in this section, in which São Paulo journalist Marcos Augusto Gonçalves takes filmmaker Glauber Rocha’s 1976 documentary on the funeral of canonical Brazilian modernist painter Emiliano Di Cavalcanti, as a springboard for a digest history of Brazilian modernism.

Section III offers exciting new takes on the centrality of the written and spoken word for Brazilian modernism, through the lens of the resurgence of interest in Brazilian 19th-century poet Joaquim Sousândrade by Concrete and Neoconcrete poets and artists during the 1950s through 1970s. University of Zurich literary theorist Eduardo Jorge de Oliveira centers this poetic recovery on a legendary 1971 meeting of Haroldo de Campos and Hélio Oiticica at New York’s Chelsea Hotel, with utterly convincing formal analyses centered on the simultaneous construction and fragmentation of the written word and the status of the page as field, surface, or skin.

São Paulo poet and translator Simone Homem de Mello’s essay continues this attentiveness to poetic form by analyzing Sousândrade (1833-1902) and German poet Arno Holz (1863-1929) as key precursors for spatiality and sonic montage among Brazilian Concretists. Finally, University of Campinas literary theorist Eduardo Sterzi brings Sousândrade into the present by tracing connections between the fraught status of Indigeneity and the natural world in Sousândrade’s work to the peripatetic works of contemporary Brazilian artist Paulo Nazareth.

Some quibbles — the term Concretism is not defined, and it is often collapsed with the idea of constructivism. This was not uncommon among Brazilian artists, poets and critics, but it would have been helpful to have greater specificity about the terms and their usage across the time periods and institutional contexts discussed in the essays. Some essays lack supporting images, or include images that are not obviously related to nearby text. Additionally, since the collected essays resulted from a conference, they understandably vary widely in scope and style, and are only loosely tethered to the overarching narrative.

More broadly, in lieu of compensating for Brazil’s “lack” of a strong visual arts tradition with recourse to literary traditions, could we identify important spatial traditions in architecture, land management and the organization of urban and rural settlements? Concrete poetry’s play with spatiality could be linked, as in Sterzi’s essay, to the natural world. However, like Oliveira and Homem de Mello, I would also emphasize Concretism’s attention to the poetic ordering of modern urban experience. Concretist and Neoconcretist artworks respond to the social structures and phenomenological feeling of the city sensorium found in works of Brazilian modernism such as Mario de Andrade’s celebratory Pauliceia desvairada (1922) as well as Giberto Freyre’s more equivocal Sobrados e mucambos (1936), and in Brazilian architectonic forms both modernist and informal (i.e., the favela).

For Brazilian modernism, the space of the page is the space of urban flux rather than that of a Parnassian ideal — Brazil’s aesthetic traditions reaching back to Camões’ episodic, globe-circling Lusiads rather than the static idyll of an English landscape painting or French pastoral poem. Sousândrade might remain central to this retelling of Concretism, given his strong poetic gestalt: cinematic scenes set apart from an endless background susurration, sharp images amid noise having just as much to do with the visual as the verbal, with form as well as feeling.

Art historian Adrian Anagnost is Jessie Poesch Assistant Professor in the Newcomb Art Department at Tulane University. Anagnost’s book Spatial Orders, Social Forms: Art and the City in Modern Brazil will be published in May 2021.

Related Articles

A Review of Bodies Found in Various Places

This bilingual anthology of Elvira Hernández, translated by Daniel Borzutzky and Alec Schumacher and published by Cardboard House Press, offers a comprehensive entry point into the work of the Chilean poet. The translators’ preface offers a valuable introduction that provides important context to her work and explains aspects of her poetry present in the volume, such as Hernández’s self-effacing “ethics of invisibility,” an ars poetica in which the poems stand in front while the poet hangs back, in a call to observe rather than to be observed. In this sense, Hernández has long written from the edges of Chile’s public life, partly by choice, partly by necessity: her birth name is Rosa María Teresa Adriasola Olave, but she adopted the pseudonym of Elvira Hernández under the Pinochet dictatorship.

A Review of An Ordinary Landscape of Violence

When first reading the title, An Ordinary Landscape of Violence, I asked myself if there is really anything “ordinary” about a landscape of violence? Preity R. Kumar argues that violence is endemic to Guyana’s colonial history and is something that women loving women (WLW) contend with and resist in their personal and public lives.

A Review of Lula: A People’s President and the Fight for Brazil’s Future

André Pagliarini’s new book arrives at a timely moment. During the summer of 2025, when the book was released, the United States began engaging in deeper debates about Brazil’s political situation. This shift was tied to the U.S. government’s decision to impose 50% tariffs on Brazilian products—the highest level ever applied to another country, matched only by India. In a letter to President Lula, Donald Trump’s administration justified the measure by citing a trade deficit with Brazil. It also criticized the South American nation for prosecuting one of Washington’s ideological allies, former president Jair Bolsonaro, on charges of attempting a coup d’état. Sentenced by Brazil’s Supreme Court to just over 27 years in prison, the right-wing leader had lost his 2022 reelection bid to a well-known leftist figure, Lula da Silva, and now stands, for many, as a global example of how a democracy can respond to those who attack it and attempt to cling to power through force.