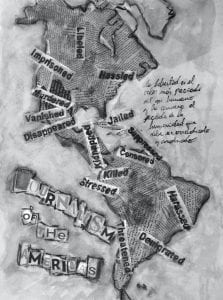

What’s New in Latin American Journalism

An Overview

From deep disappointment to exciting new times: if that were a good title, it would be the title of this story.

Just three years ago, after spending 17 years as a political correspondent and columnist with major Buenos Aires newspapers, I took a break from Argentina’s media. Journalism had been my life, but like so many reporters of my generation, who had experienced the good days of journalism, I grew disenchanted and sad about what it had become.

In Argentina, there was little talk about the death of newspapers. We did not live the widespread disaster of the United States press, with papers closing down, thousands of reporters being laid off and the traditional business model for print journalism in agony. But my generation was leaving the newsroom, looking to the future with uncertainty—when not hunting for a different profession altogether.

Today, the landscape has changed dramatically. A new wave of independent, forward-thinking and critical journalism is spreading throughout the continent. This journalism is not in the hands of young, new reporters: it is the experienced journalists of my generation shaping a new model of journalism nurtured by his and her (our!) frustration with Latin America’s mainstream media.

Common Ground

There is of course no such thing as Latin American journalism. Our countries and experiences are different, but most of us share some common problems.

To different degrees and at varying speeds, the worldwide crisis of the traditional media—decrease of paper readership, migration to digital platforms, changes in the information paradigm, lack of a new business model—is beginning to hit most Latin American countries.

Throughout the continent, readers (and often even the reporters) ignore who actually owns media companies. In many cases, the particular interests of owners allow for little editorial independence; political ties hide behind a façade of political independence.

We also share, in very general terms, low salaries, corruption in the newsroom, low professional standards and unfair internal promotion rules, which bring to the top the bureaucrat and the obedient individual—ready to censor their subordinates—instead of the hard working, talented reporter.

For the most part, content production is in the hands of large media companies; the independent bloggers, the high-quality information website, are few and far between. In part, the lack of growth until recently in this area comes from the fact that Internet connectivity is deeply uneven throughout the continent.

Local funding for independent media outlets is very hard to come by. The local capitalist is still fond of the traditional media and their traditional game. But we also have common advantages.

We share the great, unique advantage of a continental language, Spanish (with, of course, the exception of Brazil and Portuguese, which is a world of its own).

We are the fastest growing region in the world in Internet connectivity (23 percent in 2009, though the penetration rates are still relatively low). This creates a special and emerging opportunity for the development of new media outlets: costs are relatively low, structures small, and one of the great historical impediments for building a regional presence—the financial and many practical problems of continental distribution—has disappeared.

The growing Internet market is attracting the interest of European, Arab and Chinese companies and organizations—which goes hand in hand with the impressive new wave of economic interest in the region. One of the major funders for new digital outlets in the region is U.S. philanthropist George Soros’ Open Society Foundation, which up until three years ago had shown almost no interest in Latin America.

Finally, we are in the presence of a generation of experienced reporters with entrepreneurial spirit and a strong self-awareness of being the avant-garde of a journalistic revolution.

The New Wave

On March 2010, my husband and colleague Gabriel Pasquini and I launched el puercoespín, a digital magazine and our own personal experiment with new media. As part of our exploration of new ways of narrating the world and forecasting the journalisms of the future, we started drawing a narrative map of Latin America’s new media experiences.

In Colombia, we found La Silla Vacía, founded by our friend Juanita León, who has the skills and talent of a solid editor and the determination and strength of a business entrepreneur. Her website, which has been online for almost two years now, is an independent attempt to cover the powerful in Colombia—in León’s own words, the site deals with “how power is exercised”—in ways the traditional media never have in her country. It is a successful enterprise, hosting more than sixty political blogs and with an active participation from a growing audience.

In El Salvador, we found El Faro, the most unlikely digital publication. El Faro is the brainchild of Carlos Dada, who in 1998 had the crazy idea of launching an Internet publication in a country emerging from a cruel civil war and with almost no Internet connections—he did it out of lack of funds more than of clairvoyance about the future of journalism. El Faro specializes in hardcore investigative journalism and long narrative form, carried out under very difficult circumstances. The digital publication has gained prestige and admiration throughout the continent.

In Perú, we found IDL-Reporteros, where veteran Gustavo Gorriti leads a small group of young reporters in a watchdog journalism project. They have exposed cases of corruption and abuse of power with a degree of independence and freedom almost impossible to find today in the country’s established media. Gorriti’s training requirements for his young reporters include taking classes of Krav Maga, the Israeli hand-to-hand combat technique.

In Chile, we found very diverse experiences, from Mónica González’s investigative non-profit organization CIPER for high-quality watchdog journalism, to the satirical magazine The Clinic, to a network of a dozen citizen journalism dailies.

In Mexico, we found Nuestra Aparente Rendición, a collective blog managed by writer Lolita Bosch under the premise that only civil society can save Mexico from total disaster. It posts stories, personal testimony, literature and art about the violence, in a collective effort to find a way out of the violence.

In Argentina, we found chequeado.com, a local version of the U.S. site FactCheck and a reaction against the political polarization of the country’s media.

This is an incomplete map and a work in progress. There are more websites, blogs, newspapers and magazines already changing journalism in our countries, and we expect to see many more emerge in 2011.

Spring 2013, Volume XII, Number 3

Graciela Mochkofsky, a 2009 Nieman fellow at Harvard, is the co-founder and editor of digital magazine el puercoespín (www.elpuercoespin.com.ar). She is the author of four nonfiction books, among them Timerman, El periodista que quiso ser parte del poder (1923-1999), a biography of legendary Argentine journalist Jacobo Timerman (Ed. Sudamericana, 2003). Her fifth nonfiction book, about press and politics in Argentina, is coming out in 2011. She lives in Buenos Aires.

Related Articles

New Journalists for a New World

I received a surprising phone call one day in late 1993, when I was the director of Telecaribe, a public television channel in Barranquilla, Colombia. The caller was none other than Gabriel García Márquez. “Will you invite me to dinner?” he asked me. “Of course, Gabito,” I…

Latin American Nieman Fellows

A few days after I arrived at Harvard in August 2000 to begin my work as curator of the Nieman Foundation for Journalism, Tim Golden, an investigative reporter for the New York Times in Latin America, phoned me. “Could I find a place in the new Nieman class for a Colombian…

Freedom of Expression in Latin America

In June 1997, Chile’s Supreme Court upheld a ban on the film “The Last Temptation of Christ,” based on a Pinochet-era provision of the country’s constitution. Four years later, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights heard a challenge to this ban and issued a very different…