Increasing the Visibility of Guatemalan Immigrants

The Great Raid of Postville, Iowa

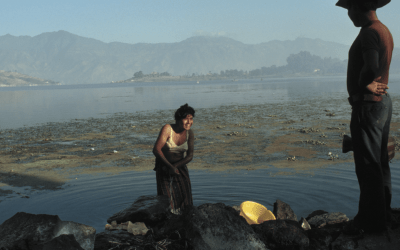

Rosario Toj, a worker under house arrest, looks out the window at an Iowa winter’s day. She was saving up money to buy her father in Guatemala a new prosthetic foot when she was caught in the raid. Photo by Jennifer Szymaszek

Guatemalans have been migrating to the United States in large numbers since the late 1970s, but were not highly visible to the U.S. public as Guatemalans. That changed on May 12, 2008, when agents of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) launched the largest single-site workplace raid against undocumented immigrant workers up to that time. As helicopters circled overhead, ICE agents rounded up and arrested 389 undocumented immigrant workers at the Agriprocessors kosher meat-packing plant in Postville, Iowa. Of those arrested, 293 (three out of every four) were Guatemalans, the rest Mexicans. Although prior raids had affected many Guatemalans, seldom before had Guatemalans been so prominent in the United States as a specific national-origin immigrant group. Also notable, a significant number of these Guatemalans were Mayas, for whom Spanish was a second language, and whose comprehension of Spanish was faulty.

After their arrest, buses from the Department of Homeland Security (the parent agency of ICE) took the undocumented workers in chains and shackles to the National Cattle Congress facility in nearby Waterloo, Iowa, which ICE had rented well ahead of the raid. This facility became a detention center, and the Electric Park Ballroom within the compound became a makeshift courtroom for expedited, “fast-track” processing of the hundreds of arrestees—in groups of ten, with nine of these groups being processed daily. ICE officials, supported by other federal and state enforcement units, pressured the arrested migrants to plead guilty to the felony crime of “aggravated identity theft” for their use of Social Security numbers not assigned to them. Pleading guilty to the slightly lesser felony of Social Security fraud would mean accepting a five-month detention (nearly the maximum sentence) in a U.S. federal prison, and subsequently being deported without a hearing. If they refused to plead guilty, they would spend an indefinite time (at least two years) in prison before facing trial on maximum charges and being deported. Because they were being processed in groups, at an unprecedented speed and without adequate access to legal counsel (the lawyers for their “defense” were criminal rather than immigration lawyers, and each lawyer handled some 17 cases), the immigrants had virtually no time to consider their options. Many of them did not even understand what a Social Security number was.

In the end, 270 of the original 389 arrestees (and of the 306 charged criminally) were found to have used the Social Security numbers of real people, and these were primarily the unlucky ones imprisoned. Most of the 270 convicted—232 of them (86 percent) being Guatemalans—pleaded guilty, in order to be deported as quickly as possible and reunited with family members back home. After being charged, over 40 of the arrested migrants, mostly women, were released from prison for “humanitarian” reasons, mainly to care for their children. But the conditions of their release were far from humanitarian: they were not permitted to work to provide for their children, and they had to wear heavy ankle shackles/GPS devices that required daily recharging while on their ankles. Moreover, many were separated from family members, who served prison time in other states and were then deported.

There was another significant dimension of this case: Agriprocessors’ massive violation of U.S. labor laws, such as withholding pay, employing under-age children, as well as exposing workers to toxic chemicals and dangerous machinery. Some of these charges were already being investigated before the raid; they also led to debates within Jewish communities about whether these abuses violated the standards for kosher-certified products. But when the time came (June, 2010) for the trial of Agriprocessors’ owner Sholom Rubashkin regarding those 9,000+ blatant labor violations, he beat these charges, because the jury simply did not believe the testimony of the immigrants, including the children who had worked there under-age. (In a separate trial in June 2010, however, Rubashkin was convicted on charges of financially fraudulent practices, some involving practices vis-à-vis immigrant workers.)

In the aftermath of the raid, the Postville case has raised major debates about ICE workplace raid policies directed against undocumented migrant workers. This was by no means the first mass workplace raid. But the specific novelty of this event was the en-masse accusation of the several hundred arrestees with a criminal violation of the law, “aggravated identity theft,” a felony rather than an administrative or civil violation of the law. (Almost none of the arrestees had a prior criminal background). From the perspective of ICE, the Postville operation was initially declared to be a major “success” (ICE Press Release, 5/23/08). It also upped the agency’s compliance with quotas for deportation under the ICE program “Endgame,” designed in 2003 to find and deport as many deportable immigrants as possible. Longer-range, ICE had intended to establish the Postville raid as a precedent and model for future mass raids against immigrants using false Social Security numbers.

But it never became a precedent. Among various factors was the significant national publicity about the methods used in this raid—first exposed in the national spotlight when court translator Erik Camayd-Freixas went public in June/July 2008 with a detailed account of all that he had seen. This was followed by Congressional House Judiciary Committee hearings in July. In addition, many different aspects of the raid were kept in the national public spotlight for over two years by the New York Times both in news coverage (primarily by Julia Preston) and in editorials. In subsequent workplace raids (such as in Laurel, Mississippi, in August 2008), criminal charges were leveled only against undocumented workers who had actually committed crimes. In April 2009, a Colorado judge halted an investigation into ID theft charges against undocumented immigrant workers on the grounds that the investigation violated their rights. And in May 2009, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that the felony of “aggravated identity theft” cannot be applied to criminalize undocumented immigrants unless they “knowingly” use the Social Security number assigned to another actual person. In this respect, while Postville was a human tragedy for the immigrants, it backfired as a long-term strategy for ICE.

While failing to become a precedent, the Postville raid was emblematic of the excesses of U.S. “enforcement-only” immigration policies of the early 2000s, with its mass criminalization and deportation of undocumented workers. It revealed just how deeply exclusionary anti-immigrant measures had become embedded since the landmark 1996 laws—affecting Legal Permanent Residents as well as undocumented immigrants—that stripped away rights and services for all non-citizens. Furthermore, it highlighted the goals of ICE’s “Endgame” deportation program that was part of the post-9/11 national security agenda.

THE VIEW FROM GUATEMALA

From the viewpoint of the Guatemalan immigrants, Postville revealed migration’s downsides in the beginning of the 21st century: the realities of family separations and cross-border family disruptions and damages. Some of the deportees were returned to Guatemala without their U.S.-born children. Such traumatic family separations and resulting damages were graphically shown in Public Broadcasting System’s “Frontline” on May 11, 2010, in the segment “In the Shadow of the Raid” (made by Greg Brosnan and Jennifer Szymaszek, see next article). Many of the Postville migrants returned to Guatemala not as respected family members sending vital remittances to their hometowns, but humiliated and owing thousands of dollars they had borrowed to get to the United States in the first place. In two of the main towns of origin of the Postville migrants—El Rosario (Sacatepequez province) and San Andrés Itzapa/San José Calderas (Chimaltenango province)—there were still no viable jobs for the deportees, and they were forced to scramble for part-time work just to pay the interest on their loans. Obviously, they were unable to help family members pay medical and other expenses, as they had intended to do when they uprooted their lives and embarked upon the dangerous, life-risking routes through Mexico to get to the United States. Some were experiencing Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder after the ordeal, especially those who had previously been victims of the Guatemalan army’s great repression during the early 1980s.

Yet, as Guatemalan anthropologist Ricardo Falla pointed out, some of the victims were able to exercise “agency”: one Guatemalan worker at Agriprocessors, for example, escaped the raid by hiding in a refrigerator for 15 hours (Prensa Libre, 7/31/08). After the raid, others obtained protection at St. Bridget’s Catholic Church, and support from various U.S.-based organizations such as the ACLU. In addition, a few Guatemalan agencies and foundations (e.g. “FUNDAGUAM,” linked to the Catholic Church) and Guatemala’s Foreign Minister denounced the raid; his Vice-Minister for Migrant Affairs later visited Postville. Guatemala’s Nobel Peace Laureate, Rigoberta Menchú, also went to Postville to show solidarity.

Meanwhile, the tale of the Postville raid is being preserved for current audiences and future generations. It has inspired films and plays in both Guatemala and the United States— for example, by Guatemalan-American film-maker Luis Argueta (AbUSAdos: La Redada de Postville) and Colorado playwright Don Fried (Postville). While the Postville Guatemalans will not benefit directly from these manifestations of solidarity, their trauma may spare other migrants such extreme violations of legal and human rights. And as a group, they will be remembered as an important collective social actor in Guatemalan/U.S. migration history.

Fall 2010 | Winter 2011, Volume X, Number 1

Related Articles

Guatemala: Editor’s Letter

The diminutive indigenous woman in her bright embroidered blouse waited proudly for her grandson to receive his engineering degree. His mother, also dressed in a traditional flowery blouse—a huipil, took photos with a top-of-the-line digital camera.

Making of the Modern: An Architectural Photoessay by Peter Giesemann

Making of the Modern An Architectural Photoessay by Peter Giesemann Fall 2010 | Winter 2011, Volume X, Number 1Related Articles

First Take: Never Again

I traveled to Guatemala for the first time in late 1980, believing, with the breezy confidence of a 20-something, that my photographs of Guatemala’s war—army, guerrillas and terrified civilians—would bring me photographic stardom…