Reading “La Masacre de Panzós” in Panzós

On the 32nd Anniversary

I am not afraid. I am not ashamed. I am not embarrassed. I cannot tell lies because I saw what happened and other people saw it, too. That is why there are so many widows and orphans here…the blood of our mothers and fathers ran in the streets. They tried to kill me, too. I had to throw myself in the river. I lost my shoes. The current carried me away. My body hit rocks in the river. When I finally got out, I was covered with mud and thorns. But this happened to many people. The army and the plantation owners did this because they don’t like us. They took advantage of us. But we are still alive. They thought they could always treat us like animals, that we would never be able to defend ourselves. But we also have rights. We have the same rights and laws as they do. I decided to speak today because I was in the plaza the day of the massacre. Today, I make my testimony public. We must tell everything that happened to us in the past so that we will not have fear in the future. We speak because we are not afraid. We speak from the heart.

—María Maquín, May 29, 1998

As an engaged anthropologist and human rights advocate, I accompany people seeking justice in the communities where I work, seeking to make scholarly contributions to help them in their endeavors. That’s why in 1997 and 1998, I directed the historical research to reconstruct four army massacres for the Guatemalan Forensic Anthropology Foundation’s (FAFG) report to the Commission for Historical Clarification (CEH, the Guatemalan truth commission). The FAFG investigation of the 1978 Panzós plaza army massacre of Q’eqchi’ Maya peasants began in September 1997. We gathered nearly 200 testimonies from massacre survivors and witnesses, reviewed municipal archives and death registers, and conducted an exhumation of the mass grave of victims.

Twenty years after the massacre, on May 29, 1998, we returned the remains of the victims to the community for reburial and participated in the two days of community commemoration, Catholic mass, and Mayajek (Maya religious ceremony). At the reburial, I was struck by the words of María Maquín, who was 12 years old at the time of the 1978 army massacre. She survived because her grandmother, Mamá Maquín, fell on top of her when hit by army fire. As one of the neighbors, doña Manuela, remembers: “La señora Rosa Maquín (Mamá Maquín) was with her granddaughter. She was on the municipal steps. She ended up there on the ground. The old woman took a bullet. They blew her head off.”

At the 1998 reburial, the words of María Maquín and others broke a silence that had reigned in Panzós since the massacre. Over the past 12 years, I have written extensively about both the Panzós massacre and the silencing of Maya women—the way in which the army makes use of gender inequality and racism in Guatemala to create a climate of suspicion around the testimony of women survivors like María Maquín and Rigoberta Menchú. I have also carried out extensive research on the history of land tenure in Panzós, as well as archival research on media coverage of the massacre. In November 2009, with support from Fundación Soros Guatemala, I published La Masacre de Panzós–Etnicidad, Tierra y Violencia en Guatemala (F&G Editores).

In March 2010, my publisher Raúl Figueroa Sarti and human rights advocate Iduvina Hernández presented the book at the Centro Cultural de España in Guatemala City. At the end of the presentation, two teachers from Panzós approached Raúl and Iduvina to ask if the book could be presented in Panzós on the 32nd anniversary of the massacre. Without hesitation, they both agreed to make the eight-hour trip to rural Panzós for the occasion. Three weeks later, the teachers contacted Raúl to let him know that they had confirmed participation of more than 400 people and would like the author (me) to attend the event.

This invitation was both an honor and a challenge. I had not been in Guatemala since 2007 after a series of threats against my life. Moreover, Raúl is also my husband and we have a five-year-old daughter. We travel as a family or one of us stays with her in New York. This book presentation required his presence as publisher and mine as author, so it also meant taking Valentina with us. As parents, this travel raised security and health concerns. It is a long drive for a little girl who gets motion sickness. Panzós, in an isolated region, is not a tourist site. There is no relief from the humidity and sweltering heat. Malaria and tuberculosis continue to be major problems. Poverty is widespread; land tenure remains inequitable. Corrupt local elites continue to use violence to marginalize Q’eqchi’ Maya peasants throughout the region, despite the provisions of the Guatemalan Peace Accords signed nearly 14 years ago.

Despite these concerns, we decided to accept the invitation and invite friends and colleagues to join us. Our 25-year-old daughter Gabriela, who lives in Costa Rica, volunteered to accompany us on our trip as well. As Gabriela was a child of the Guatemalan diaspora, Panzós also resonated with her. So, on May 28, 2010, we arrived in Panzós with a caravan of five vehicles with 26 people from the United States, Canada, Costa Rica and Guatemala. I met people who traveled to Panzós from afar, such as Guatemalan exile Byron Titus, who traveled from Massachusetts with his 8-year-old son so that he might better understand his father’s exile and ongoing commitment to justice. On this day, we were all accompanied.

The presentation was held in Panzós’ cavernous municipal hall built of cement blocks. In all, some 650 people attended the event, which was presented via live feed in Spanish with translation to Q’eqchi’. We donated copies of the book to the library and local schools. Still, dozens of local Q’eqchi’ Maya stood in line to buy 260 copies of the book and then waited patiently for me to sign it. Sold at less than cost for 30 Quetzales (less than $4), the book cost more than most Panzós residents earn in a day. Several people asked to have the receipt for their purchase written for “massacre survivor.” Renowned Guatemalan poet Carolina Sarti and Iduvina Hernández commented on the book. Both Carolina and Iduvina had been in Panzós as journalists shortly after the massacre. They spoke about the marches in Guatemala City and the wave of terror that followed the massacre. Then, María Maquín spoke. It was the first time I had seen her since 1998, when she was 32 years old, thin, brave, but hesitant to speak in public. Now, at 44, she is heavier and stands solidly before her community. She does not equivocate when she speaks. She is a leader.

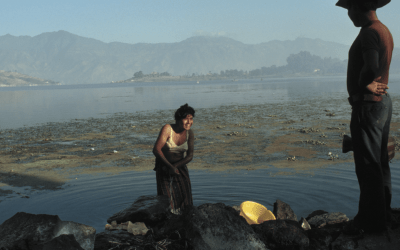

Carolina, Iduvina and I each read some of the words of María Maquín’s testimony from my book. As we spoke, I wondered how she felt about our appropriation of her words as she listened to Bernardo Caal translate what we said to Q’eqchi’. María is a peasant leader. She is also illiterate and a monolingual Q’eqchi’ speaker. I looked at her hands and wondered how many thousands of tortillas she had hand-patted since 1998, how many thousands of pieces of clothing she had scrubbed and wrung out by hand. Today, she lives in the same poverty her grandmother was protesting when she was killed in 1978. Though some things have changed in Guatemala in the past three decades, much has not.

During the ceremony, María gave me a somewhat rumpled piece of paper. I unfolded it to find a photocopy of her grandmother’s cédula (national ID) photo—the only known photo of Mamá Maquín. In the hallucinatory heat on the auditorium stage in front of hundreds of local peasants, teachers and students in Panzós, I remembered Ariel Dorfman’s writing about photos of the disappeared in Chile. One poster bearing images of many disappeared had two blank spaces above the names, as two of the men were too poor to even have a photo.

And then María Maquín stands up to speak. She thanks us for the event. “Today’s event is important so that no one ever forgets what happened on May 29, 1978,” she says. “Everything they said is truly what happened.” And I see that rather than appropriate her words, we have validated her experience. My book, our presence, this event reminds everyone that the massacre happened and that it was awful. She directs her comments to the youth and teachers. She says: “Know the truth. Read this book and share this book so that everyone knows this history so that it does not happen again.” She stands firmly and says, “I am going to repeat my own words. I am not afraid. I am not ashamed. I am not embarrassed. I am telling you what happened because I am alive. It was land problems that provoked this massacre and we continue to be abandoned in our villages. We do not have enough land to feed our families.”

With great emotion, she continues, “I saw what the army does. I lived through what the army did. We should never agree to an army post here in Panzós.” Then, she challenges the youth. “The army can kill you,” she says, “I don’t want you to have to live through what I lived through. If you say nothing against the army base, they will say you want it. You must speak up.”

With great formality, a group of teachers and local peasants then read a petition in Spanish and Q’eqchi’ as they presented it to María Eugenia Morales de Sierra from the Human Rights Ombudsman’s Office. They asked her to take their opposition to the army base to the president of Guatemala. The petition has 10 pages with 668 signatures—514 of which are thumb prints with names printed upon them. Each page of signatures carries a circular stamp—Comité de Víctimas de la Masacre, Panzós 29-05-1978—and includes the name of the village or hamlet (Cahaboncito, Tinajas, La Esperanza, Chichim, El Cacao). These are the names of the small, isolated communities on the outskirts of the municipality of Panzós. These are the communities that lost hundreds of people to La Violencia in the late 20th century. The 1978 massacre was the beginning, and it was followed by waves of selective violence that today has diminished, but not ended.

María Maquín is right about their land battles. The Q’eqchi’ who live in these communities lost their property to local elites who took advantage of Cold War ideologies and made alliances with the army and national elites, naming anyone who spoke for justice or land reform a communist—a death sentence during La Violencia. Such was the climate of injustice during the internal armed conflict (1964-1996) that led to genocide, (1980-1982) and ultimately to the razing of 626 indigenous villages, leaving 200,000 people dead or disappeared.

As I watched María Maquín speak in Q’eqchi’ and then listened to Bernardo’s translation in Spanish, I thought of the many times colleagues have challenged the “authenticity” of speakers like María. They question a peasant woman’s capacity to develop her own ideas. They assert that someone else is speaking through her, as they refuse to believe that the human rights discourse she presents could possibly belong to her. I remembered John Beverly’s work on testimony in which he suggests that scholars should worry less about how they appropriate Rigoberta Menchú and concern themselves more with seeking to understand and appreciate how they themselves might be appropriated by her. I smiled as María Maquín appropriated the occasion of my book presentation to condemn the proposed construction of a new military base in Panzós, although to be fair, I knew she would do this, as the community had asked for our approval to include their petition in the book presentation.

María Maquín and her 667 neighbors are right to oppose this new army base. As they state in their petition, neither the intellectual nor material authors of the massacre or any of the other violence meted out against the Panzós community have ever been brought to justice. The claims of the victims and survivors of this violence languish in the courts, as do their claims for the return of their lands. The 514 thumb prints are a testament to ongoing economic and cultural marginalization that denies the most basic of rights to the majority Maya in Panzós and throughout Guatemala. The installation of an army base in Panzós would violate the ILO Convention 169 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples, which establishes the obligation of the state to consult with indigenous peoples on decisions that affect their development and territory. Further, it would violate Article 30 of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which states: “Military activities shall not take place in the lands or territories of indigenous peoples, unless justified by a relevant public interest or otherwise freely agreed with or requested by the indigenous people concerned.”

The people of Panzós, like survivors of genocide throughout Guatemala, need to be heard. On an individual level, they need to have the veracity of their lived experience of survival validated. On a national level, Guatemala as a society needs to come to terms with the massacres, disappearances and assassinations that happened in the late 20th century. Guatemala needs to move beyond blaming the victims and recognizing the responsibility of the state and the army for the violence. It is important for the country to come to terms with the truth today as we move into the second decade of the 21st century, because the intellectual and material authors of genocide and other crimes against humanity have yet to be processed in a court of law. The violence in which Guatemala lives today is derived from the impunity established by these war criminals who continue to hold power in local and national political structures, as well as in clandestine groups. María Maquín and her neighbors deserve our support as they continue to struggle for justice for massacre survivors and seek to halt the building of a military post in Panzós.

Fall 2010 | Winter 2011, Volume X, Number 1

Related Articles

Guatemala: Editor’s Letter

The diminutive indigenous woman in her bright embroidered blouse waited proudly for her grandson to receive his engineering degree. His mother, also dressed in a traditional flowery blouse—a huipil, took photos with a top-of-the-line digital camera.

Making of the Modern: An Architectural Photoessay by Peter Giesemann

Making of the Modern An Architectural Photoessay by Peter Giesemann Fall 2010 | Winter 2011, Volume X, Number 1Related Articles

Increasing the Visibility of Guatemalan Immigrants

Guatemalans have been migrating to the United States in large numbers since the late 1970s, but were not highly visible to the U.S. public as Guatemalans. That changed on May 12, 2008, when agents of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) launched the largest single-site workplace raid against undocumented immigrant workers up to that time. As helicopters circled overhead, ICE agents rounded up and arrested …