Dancing in the Diaspora

El Baile de los Negritos

The hundreds of yucuaiquinenses that have found their way to somerville in the last two decades have preserved their special religious traditions, sharing them with the community and passing them on to their children. The two municipalities have become sister cities, united through dance. Photo by Sebastian Chaskel

Dance unites Yucuaiquín, a small town in eastern El Salvador, with the city of Somerville in eastern Massachusetts. Traditionally a city of Greek, Irish, Italian, and Portuguese immigrants, the only quality Somerville had in common with Yucuaiquín before the 1980s was a population with vibrant Catholic beliefs and traditions. The hundreds of Yucuaiquinenses that found their way to Somerville in the past two decades brought with them a unique set of religious traditions—among them a dance in honor of Saint Francis of Assisi, the patron saint of animals and the environment, and of Yucuaiquín.

El baile de los negritos—literally the dance of the little black folk—has been a Yucuaiquinense tradition since time immemorial. Legend has it that Yucuaiquín was once a small hamlet hidden in a valley, until a group of hunters found a wooden figurine of Saint Francis of Assisi under an amáte tree up in the mountains. Their attempts to bring the figure back to the hamlet were futile; it reappeared over and over again on the mountain, under the amáte tree. Eventually, the entire town moved and established itself around the tree, honoring its newly found patron saint. Yucuaiquinenses then and now ask Saint Francis for favors, offering to dance el baile de los negritos if their requests are granted. They believe Saint Francis is generous to those who fulfill their obligations to him, but stern to those who fail to comply with their promises.

Since the 1980s, thousands of Yucuaiquinenses have migrated to the United States. While Yucuaiquín is a town composed of some 10,000 people, according to a Somerville-based Yucuaiquinense organization, an estimated 2,500 Somerville residents identify themselves as Yucuaiquinenses. Now they dance el baile de los negritos in order to fulfill promises to Saint Francis of a more contemporary nature: some thank their patron saint for safe arrival in the United States after an arduous journey; some follow the tradition in order to teach their U.S.-born children to continue to celebrate Salvadoran culture and religion in their new homeland.

The upbeat el baile de los negritos is danced during the months leading up to Saint Francis’ Day in October to the fast-paced music of el tambór (drum) and el pito (recorder), played by individuals in Yucuaiquín and a tape recorder in Somerville. Dancers swing el chin-chin (maracas) in one hand and hold un ramo (bouquet) behind their backs as their feet move fluidly from side to side; wooden masks covering the performers’ faces mockingly depict white men with big eyes and wide mouths. The explanation behind the name—los negritos—and the costuming, is unknown: they are traditions that have been evolving since pre-Hispanic times and now offer no clarification.

Following a performance of el baile de los negritos at the Somerville Museum last year, Somerville’s mayor traveled to Yucuaiquín to sign a sister-city agreement. Yucuaiquín’s officials travel often to Somerville to campaign and update Yucuaiquinenses in the area. Yucuaiquinenses in both countries are constantly in touch through telephone, e-mail, money transfers, and the time-honored dance they all share. For Yucuaiquinenses in both countries, el baile serves as a conduit between Yucuaiquín and their new homes, between past and present, and between generations. It has become a crucial component of the modern Yucuaiquinenses’ struggle to adapt themselves to a new land while remaining true to their roots. While their lives may be drastically different in U.S. urban centers than they were in provincial Yucuaiquín, el baile and its saint travel with the people of Yucuaiquín.

The hundreds of yucuaiquinenses that have found their way to somerville in the last two decades have preserved their special religious traditions, sharing them with the community and passing them on to their children. The two municipalities have become sister cities, united through dance. Photo by Sebastian Chaskel

Bailando en el diaspora

El baile de los negritos

TEXTO POR SEBASTIAN CHASKEL | FOTOS POR SEBASTIAN CHASKEL Y ALONSO NICHOLS

El baile une a Yucuaiquín, una ciudad en el oriente de El Salvador, con la ciudad de Somerville, en el oriente de Massachussets. Históricamente Somerville ha sido una ciudad de inmigrantes griegos, irlandeses, italianos y portugueses, y la única característica que tenía en común con Yucuaiquín antes de la década de los 80 era una población con intensas creencias y tradiciones católicas. Los cientos de yucuaiquinenses que se asentaron en Somerville durante las últimas dos décadas trajeron consigo tradiciones religiosas particulares—entre ellas un baile en honor a San Francisco de Asís, el santo patrón de los animales y del medio ambiente, y de Yucuaiquín.

El baile de los negritos ha sido una tradición yucuaiqiunense tan vieja como la memoria. La leyenda nos dice que Yucuaiquín era una aldea escondida en un valle, hasta que un grupo de cazadores encontró una figura de madera de San Francisco de Asís en el monte, debajo de un árbol de amate. Sus intentos de traer la figura a la aldea fueron en vano ya que volvía a aparecer en el monte bajo el árbol de amate. Eventualmente toda la población se trasladó al monte alrededor del árbol en honor a su nuevo santo patrón. Yucuaiquinenses en ese tiempo, y hoy en día, le piden favores a San Francisco, y le ofrecen bailar el baile de los negritos si sus peticiones son concedidas. Ellos creen que San Francisco es generoso hacia los que cumplen con sus obligaciones hacia él, pero riguroso hacia los que no llevan a cabo sus promesas.

Desde los le década de los 80 miles de yucuaiquinenses han migrado a los Estados Unidos. Aunque Yucuaiquín es una ciudad de 10.000 personas, según una organización de yucuaiquinenses en Somerville, hay aproximadamente 2.500 residentes de Somerville que se identifican como yucuaiquinenses. Hoy en día bailan el baile de los negritos para cumplir con promesas a San Francisco de una realidad contemporánea: algunos le agradecen al santo patrón por haber llegado a salvo a los Estados Unidos después de un viaje difícil, mientras otros continúan la tradición para enseñarles a sus hijos nacidos en los Estados Unidos a practicar la cultura salvadoreña y su religión en su nuevo ambiente.

El animado baile de los negritos se baila durante los meses antes del día de San Francisco de Asís, en octubre, al ritmo rápido del tambor y del pito, instrumentos tocados por personas en Yucuaiquín y escuchados en una casetera en Somerville. Los bailadores agitan el chin-chin (maracas) en una mano mientras en la otra llevan un ramo de flores detrás de sus espaldas mientras mueven sus pies de lado a lado; sus caras escondidas detrás de máscaras de madera que se burlan de hombres blancos con ojos grandes y bocas anchas. La explicación detrás del nombre—los negritos— y la vestimenta son de origen desconocido: son costumbres que se han desarrollado desde los tiempos pre-hispánicos y no ofrecen aclaración.

Después de una demostración del baile de los negritos en el Museo de Somerville el año pasado, el alcalde de Somerville viajó a Yucuaiquín para firmar un acuerdo de ciudades hermanas. Los funcionarios de Yucuaiquín viajan a menudo a Somerville para hacer campaña y poner al día a los yucuaiquinenses en el área. Yucuaiquinenses en los dos países están siempre en contacto a través del teléfono, correo electrónico, transferencias de dinero, y el duradero baile que todos comparten. Para los yucuaiquinenses el baile sirve como un vínculo entre Yucuaiquín y sus nuevos hogares, entre el pasado y el presente, y entre generaciones. Se ha vuelto un componente importante en la lucha moderna de los yucuaiquinenses de adaptarse a un sitio nuevo y permanecer fieles a sus raíces salvadoreñas. Aunque sus vidas son drásticamente diferentes en los centros urbanos de los Estados Unidos de lo que eran en su tierra natal, el baile y su santo viajan con la gente de Yucuaiquín.

Sebastian Chaskel worked with the community of Yucuaiquinenses in Somerville as a component of his anthropology coursework at Tufts University. Sebastian is now Research Associate for Latin America at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Alonso Nichols is a freelance photojournalist based at Tufts University interested in issues affecting Latin America and Latinos living in the United States. His travels and projects have taken him from México and Nicaragua to New Orleans, Los Angeles and Kentucky.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Dance!

We were little black cats with white whiskers and long tails. One musical number from my one and only dance performance—in the fifth grade—has always stuck in my head. It was called “Hernando’s Hideaway,” a rhythm I was told was a tango from a faraway place called Argentina.

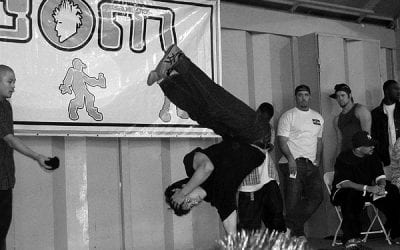

Brazilian Breakdancing

When you think about breakdancing, images of kids popping, locking, and wind-milling, hand- standing, shoulder-rolling, and hand-jumping, might come to mind. And those kids might be city kids dancing in vacant lots and playgrounds. Now, New England kids of all classes and cultures are getting a chance to practice break-dancing in their school gyms and then go learn about it in a teaching unit designed by Veronica …

Dance Revolution: Creating Global Citizens in the Favelas of Rio

Yolanda Demétrio stares out the window of our public bus in Rio de Janeiro, on our way to visit her dance colleagues at Rio’s avant-garde cultural center, Fundição Progresso. Yolanda is a 37-year-old dance teacher, homeowner, social entrepreneur and former favela (Brazilian urban shantytown) resident. She is the founder and director of Espaço Aberto (Open Space), an organization through which Yolanda has nearly …