Civil Society in a Time of Rage

Beyond Armed Actors

The conference, however, was not a Colombian lament. It was a set of constructive, mutually-informing dialogues, comparative examples, and descriptions. For example, as the Colombian representatives listened to Srilatha Batliwala, a Visiting Scholar at Harvard’s Hauser Center for Nonprofit Organizations who has never visited Colombia, describe the development and progressive influence of a mothers’ group amidst the endemic violence of Nagaland (Northern India), the value of objective comparative analysis was obvious. While James Austin of the Harvard Business School, who travels to Colombia regularly, described the hemispheric work of the school’s Social Enterprise Initiative, opportunities to create new networks and link up with existing ones arose. And so it went, as more than twenty faculty members and researchers met and discussed, resulting in a set of collaborative initiatives.

CIVIL SOCIETY

Civil society in general is often regarded as a sort of Third Estate—an amorphous mass of commoners whose diverse interests and irregular actions stand in contrast to the sharply defined and organized projects of the State and other powers. Impressions of Colombia are no exception. As guerilla and paramilitary violence (and government efforts to control each) now escalates, it threatens to dwarf local needs and polarize complex interests and concerns.

An exclusive focus on resolving the armed conflict, the conference participants demonstrated, probably misses a critical distinction. It conflates the actions of insurgents and counter insurgents with other manifestations of violence. While undoubtedly both are related, perhaps symbiotically, in many regions, critical analytical distinctions and causes separate one from the other. Unfortunately, the failure to distinguish between the two diverts national and international attention and resources away from more localized patterns of violence while also permitting the armed conflict to spark or sustain local cleavages, and confuse the resulting relationships and sentiments.

At the same time, in Colombia, as in many countries since the end of World War II, the number and interests of organized citizen groups—whether formally recognized Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) or informal neighborhood, community, and other interest groups—have increased exponentially. Civil society, in general, now proactively contours a more precisely groomed global landscape. Moreover, Colombia’s 1991 Constitution empowered the national society, formally at least, through its emphasis on public participation, consultation, and consensus. Practice, however, has lagged behind formal rule making. Some argue that, again, as in most countries, it will simply take time to close that gap, and at present there are other national priorities.

However, others suggest that waiting and seeing may not be the right approach for Colombia. Civil society, they say, is not off track in its sense of timing. Though faced with some quite common organizational needs and unique conditions, there is a sense of urgency, which is not a misplaced priority in the face of increasing illicit violence.

COLOMBIA: WHY NOW?

In many countries—e.g., the former Soviet Union, South Africa, and Guatemala—and with the exception of human rights NGOs, civil society (and the international support for it) arose anew, like Phoenix, from the ashes of violence or the remains of repressive undemocratic governments. Yet, armed insurrection does not simply persist in Colombia; it is increasing. It should be noted, however, that this is not a civil war, nor is Colombia even a country at war. Most now agree that it is not the government that represses civil society but rather a set of violent actors, each voicing a liberating cry that few accept as legitimate or sincere and, which most agree must be disarmed. Colombian civil society projects do receive funding from international donors—ranging from the World Bank and Inter-American Development Bank to the Open Society Foundation, the Ford Foundation, and the MacArthur Foundation—however, most international economic support for development and strengthening of civil society has gone to where it was most notably absent: the newly independent countries of the former Soviet Union. Colombia, by contrast, already has an established, vibrant, and active set of civil society actors. So why are they now seeking to expand their profiles? Why doesn’t Colombian civil society simply wait until the current violence disappears so that it can increase its activities unencumbered? Won’t the work be easier? And won’t international support be more readily available?

Colombians, for quite good reasons, argue that civil society cannot stand aside and wait until the current warfare ends. Those at the Harvard conference stated that if a new, post-armed conflict, society takes shape without strong and prior input from civil society organizations, the resulting shape will not be a Phoenix but a Hydra, in which the old threat simply reemerges with multiple heads and no long-term peace. Just as there was no means to hold the negotiators at the government-FARC peace negotiations at San Vicente de Caguan accountable to civil society, the broad processes of participatory and deliberative democracy needed to sustain civil society in any arena will be similarly hobbled.

Civil society is not so naïve as to assume that, if it took the reins of power in negotiations or even if they sat at the table, armed insurrection would come to an end, any more than they could be expected to redirect the United States’ current focus on ending the drug trade at its source. Nevertheless, many understandings of the term “violence,” as with “peace,” have quite distinct patterns. The shadow of armed conflict has easily shifted or transformed many local cleavages and manageable disputes into major breaks with traumatic impact. Civil society is thus not naively ignoring the broad presence and influence of the armed actors. It is attempting to put their actions into appropriate local contexts. This permits a broader understanding of systemic violence and suggests the sort of immediate interventions in which the idea of peace extends beyond the cessation of warfare and acknowledges the broad systemic violence.

Despite the armed combatants’ currently high national and international visibility, they are not the principal sources of violence or cause of death. The country holds the dubious distinction of the world’s highest homicide rate—26,000 per year, or 70 per 100,000 inhabitants. However, some argue that as few as 15% of the homicides originate directly from armed conflict. Most of Colombia’s violence is the result of common crime, vigilantism, vendettas, as well as new and intricate forms of organized crime such as drug trafficking, money laundering, infrastructure sabotage and related environmental degradation.

The Colombian National Planning Department has estimated that the total gross costs of urban violence and armed conflict in the country consume an average of 4.2% of the GDP per year. That figure would probably rise significantly if one factored in the regional impacts of forced displacement, corruption, weakened judiciary, and inequitable distribution of resources. These broad and numerous ruptures of social relations and the related collapse of social capital explain, in large part, the high levels of violence as a national phenomenon, while also suggesting that regional mapping is essential for analysis and management.

In brief, Colombia’s armed conflict has obviously hindered economic development, justice, and an improved quality of life. Yet no cease-fire will simultaneously eliminate the broader patterns of violence and exclusion. Unless some of the local and regional sources of violence are identified, confronted, and reconciled, the likelihood that they will remain glossed over, or even hidden, within the frame of armed conflict increases.

There is, therefore, a growing sense that broad civil participation, through new channels and local scenarios, is essential. This, some suggest, will begin to generate the pressure needed to advance the various interests of civil society and institutionalize its presence in democratic forums, rather then having those interests simply defined or invoked by those who currently retain power through force of arms. Civil society must continue to create the means and widen the channels for active participation such that any peace process becomes both a setting for a present event and an example for future patterns of governance.

These are not unrealistic expectations. Despite a history and current infamy of violence, Colombia is the second oldest uninterrupted democracy in the Americas, after the United States. Unlike its neighbors, Colombia has not experienced coups d’état, long dictatorial regimes, concentrations of power, or power vacuums. Since 1991, the country’s constitution has formally strengthened its formal capacity for broad participatory democracy, thus improving the checks and balances on State power. As such, the country sits in a paradoxical position—suffering enormous internal violence while strengthening its local institutions and a vigorous democracy.

While the specific sources of violence vary widely due to the country’s regionalism, many suggest that a single term best encompasses the multiple causes of violence: exclusion. Exclusion is understood broadly as the simultaneous presence of, but inability of some to access, desired services, goods, educational and economic opportunities, and political voice and participation. These patterns of exclusion and related sentiments are compounded by corruption and other abuses of power and resources by public institutions.

Civil society alone cannot expect to reverse the structural issues that lead to exclusion. They will all require the broader will and powers of the State. However, as those at the Harvard conference suggested, civil society can respond first by acknowledging the pervasive and heterogeneous nature of violence, giving voice to those who can speak from such experiences, revealing the associated sentiments, and seeking ways to demonstrate that inclusion is not a gift from those who currently hold power but a right of those citizens who do not. This, they argued, would begin a process that confronts the root causes of violence in local settings and thus separates the sort of violence and related needs that civil society can manage from that which it cannot.

THE DILEMMAS OF CIVIL SOCIETY

The limited and often frustrated role of Colombian civil society within government-initiated peace processes, the inadequate impact of civil sector peace initiatives, and the dispersed nature of these local peace and development projects reveal some of the basic weaknesses of civil society.

- An absence of coordination and opportunities for reflective, critical analysis;

- Few opportunities to evaluate critically their work or for others to draw from it and adapt it in their own cases;

- The absence of ties to universities or other academic bodies, which can provide methods for analysis and forums for evaluating patterns of success and failure.

Consequently, the national and international focus on resolving the conflicts with guerrilla forces through government-led agreements has not only failed to produce peace, but has left much of civil society as a passive spectator rather than a principle actor. The dilemma of civil society is compounded by the independent nature of its few peace and development initiatives. With the exception of networks such as the Red Prodepaz and Colombian Confederation of NGOs, which was represented at the conference, most projects are relatively autonomous and geographically dispersed.

Given the variety of interests and needs, civil society actors now need access to academic and technical resources to produce and reproduce the educational and other methodological tools. These will enable civil society leaders to act jointly against violence, work locally toward reconciliation, and build or rebuild institutions as changing conditions require.

A RESPONSE AT HARVARD

In November 2002, Harvard’s David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, in collaboration with the Program on Nonviolent Sanctions and Cultural Survival at the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs, hosted a broad inter-faculty conference with an equally broad range of representatives from Colombian universities, government, private sector, and civil society organizations. The conference drew on the research experiences and initiatives of various Projects, Programs, Centers of over twenty faculty and other researchers within five of Harvard University’s schools that seemed to coincide with the participants’ expressed needs—Arts and Sciences, Law, Business, Education, and the JFK School of Government. Workshops exposed the Colombian representatives to the experiences of other societies in conflict, encouraged them to jointly rethink paradigms for engagement and participation, and illustrated methods to document, explicate, transform, and replicate experiences from Colombia’s dispersed peace and development projects to the wider community.

Prior to the conference, the Colombian participants had indicated that, despite many Colombian academics’ well-sharpened tools and other skills for analysis of their current situation, their ability to link analytical skills to practical solutions was deficient. Conversely, practitioners working at a local level felt the need to consider, analyze, and evaluate their work. They also suggested that they could benefit from sympathetic but nonetheless objective external insights and comparative experiences. In brief, Colombians did not solicit help in defining and analyzing their situation. Rather, they acknowledged the need to develop dialogue and collaboration with researchers at Harvard and jointly develop sound practical methods for inclusion in the peace process and in a participatory democracy in general.

During more than nine months of communication, coordination, and visits to Harvard by representatives of Colombian regional peace programs, universities, intellectuals, and the National Reconciliation Commission, there appeared to be a correspondence of some of the needs in Colombia and the means at Harvard to meet them. The conference workshops tested this perceived correspondence and, more importantly, considered whether experiences and methods could be transformed into a practical and theoretical collaborative initiative.

The conference format introduced the Colombian participants to specific research experiences and initiatives at Harvard. They were clustered into three areas.

-

HUMAN RIGHTS

-

CONFLICT MANAGEMENT, CONSENSUS BUILDING, AND RECONCILIATION

-

CIVIL SECTOR EDUCATION, STRENGTHENING, AND MOBILIZATION

Following the workshops, the participants, joined by Colombia’s Vice-President Francisco Santos, suggested a collaborative initiative in which communication and collaboration from the various Harvard programs would be channeled through an alliance linked to Colombia’s widely known and respected National Reconciliation Commission. Several from Harvard accepted the idea—now titled the Colombian Civil Sector Initiative—and initial exchanges, capacity building and research projects have been planned. In the broadest sense, the project will draw from the three broad research areas mentioned above and will channel communication and collaboration through the Commission to Colombian universities. They, in turn, will pass on and adapt the work in collaboration with local grass roots organizations and projects. This organizational structure is not simply efficient but also permits the sort of multiplier effect that is often absent in international projects.

The Colombian Civil Sector Initiative will, most would humbly agree, not break the fever of that country’s colera. However, it may demonstrate that “violence” has become a paralyzing gloss. By first distinguishing one form of violence—the armed conflict—from another—the product of exclusion and unrealized capabilities—the Initiative can shift some popular sentiments away from increasing frustration and cynicism. By then moving towards some of the participatory civic actions that respond to the frustrated expressions of violence, the process alone can simultaneously highlight a broad set of problems and initiate a means to approach them

Luis Fernando de Angulo is a Visiting Scholar at PONSACS and founder of the Fundación El Alcaravan, a non-profit grassroots development agency.

Rodrigo Villar is Coordinator of the Program in Philanthropy, Civil Society, and Social Change (PASCA) at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies.

Ernesto Borda, is the Director of the Institute of Human Rights and International Relations at Bogotá’s Universidad Javeriana.

Alvaro Campos is Executive Secretary of the Colombian Conciliation Commission (CNN).

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter

This is a celebratory issue of ReVista. Throughout Latin America, LGBTQ+ anti-discrimination laws have been passed or strengthened.

Editor’s Letter: Colombia

When I first started working on this ReVista issue on Colombia, I thought of dedicating it to the memory of someone who had died. Murdered newspaper editor Guillermo Cano had been my entrée into Colombia when I won an Inter American…

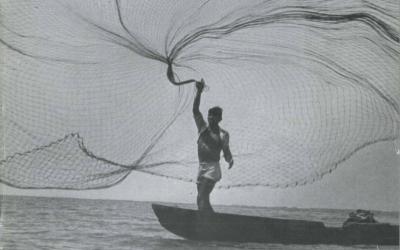

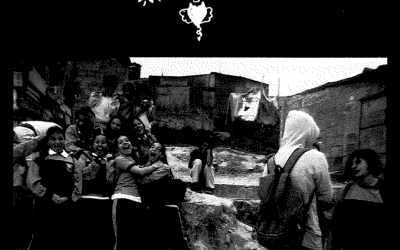

Photoessay: Shooting for Peace

Photoessay: Shooting for PeacePhotographs By The Children of The Shooting For Peace Project As this special issue of Revista highlights, Colombia’s degenerating predicament is a complex one, which needs to be looked at from new perspectives. Disparando Cámaras para la...