Traces of Memory

Art and Remembrance in Colombia

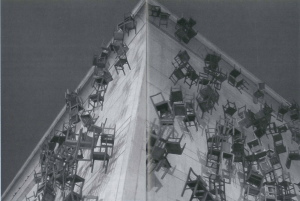

Remembrance through Art: the Palace of Justice, November 6-7, 2002. Courtesy of Doris Salcedo.

”At dawn all was desolation and ruins. Amid the rubble lay the incinerated remains of hostages and guerrillas, their weapons, also calcified, beside them. Few of the bodies retained their human form. The air exuded an unbearable, penetrating stench, record of the destruction of human life.”

— Report of the Special Inquiry Commission Report on the Palace of Justice

Some people call it the Holocaust at the Palace of Justice. November 6 and 7, 1985, were days that changed Colombia forever, the days in which impunity became entrenched in the official façade of democratic institutions and memory erased. No one knows exactly, but around 126 people died, including most of the country’s Supreme Court.

Despite desperate attempts by many, including the hostage judges themselves, to get the civilian government to negotiate with guerrillas who had taken the Palace of Justice by force, the Colombian Army immediately retaliated in a brutal way with bullets, bombs, and fire. The mostly one-sided battle lasted for two days. Few human remains were found. Nothing but ashes.

Bolivar Plaza, the site of the old Palace of Justice and its new stone replacement, is located in the very center of Bogotá’s downtown. It is a pigeon-filled plaza, filled with strolling lovers and office workers out on a lunch break. I used to work near there—a bustling oasis that all too soon buried and forgot its blood-stained witnessing.

For 17 years now, I had wanted to remember, to transform this violent event into remembrance through art. As an artist who works with memory, I confront past events whose memory has purposefully been effaced, in which the objects that bear the traces of violence have being destroyed in order to impose oblivion. In this case, I wanted to try to turn this intentional oblivion, this “no longer present” into “a still here”, into a presence. When there are no traces, only one thing remains a date, or, in this case, two: November 6th and 7th.

Last year, on those dates, we commemorated the Palace of Justice deaths for the first time, lowering 280 empty chairs from the roof of the new building, slowly, with no obvious human presence, during the two long days.

For months, I had been collecting the simple wooden chairs and confronting the tangled bureaucracies to obtain the necessary permissions. It was not an announced event, but an integral part of the Plaza life, an event that made people stop and watch and listen and remember.

This ephemeral artwork was based on the specific memory rooted on the singularity of this date, irreplaceable date for the families of the victims, and irreplaceable for anyone willing to remember. It is a date that belongs to the past but on each anniversary it announces its return, it is also a date to come. As French writer Jacques Derrida put it “ The date is a future anterior, a date is also the anniversaries to come.”

In forming this art, I needed to break with the event’s specific details, bringing it out of the past so it could become a memento, a memorandum for all of us in the present, not just for the few who actually witnessed the event. A work of art must conjoin several different events, so the same date commemorates heterogeneous events.

Derrida writes in his essay on Celan that a “date is a specter, a commemoration announces the spectral return, of that which unique in its occurrence will never return, what one commemorates will be the date of that, which could never come back.”

In Colombia, in this most violent of times, we are forced to face the emptiness and the nothingness of the loss in war. The search for meaning focuses on the irrepressible activity of remembrance, which must begin with the inscription of the date in a work of art, if it is to endure. The work of art speaks even if none of its references are intelligible. Art speaks to the other; it addresses an other an altogether other, even if it does not reach the person it is addressing. The main issue, as Derrida observes, “is that address takes place, even in the absence of a witness.” What counts is that address takes place, because the presence of some remainder, some trace of memory, “allowed us to commemorate celebrate and bless.”

In the Palace of Justice work and, indeed in all of my work, I have discovered that to construct an object invested with cultural signification, in order to make a work of art, I have to go toward the other. My work is a relationship with that person, whom I try to express. His presence is a requirement for my work. The victim of violence is prior to my work. The victims of violence invest my work with meaning. My work comes from the experience of the person to whom I am dedicating and addressing my work.

In my work on political violence, I have tried to interpret how human life is manipulated by calculations of power. I have focused on extreme forms of political violence, forceful displacement, disappearance, massacres, persecution that end in death. My work is about the ones that have been expelled from their place and have nothing left, as Paul Celan said, “the ones that are unsheltered even by the traditional tent of the sky.”

All of my work is based on individual cases that are of little interest to historians and to the Colombian justice system. In order to make a piece, I try to find individuals who have endured violence and extreme experiences. I look for individuals as faces, as real presence, but in most cases unfortunately I encounter just the impossibility of finding the person because the person is gone and all that is left is a trace and all that is felt is his silence. All that remains is beyond my possibilities, beyond my reach. There is nothing or very little I can grasp of that life that is gone long ago. This is what my work is about: Impotence, a sum of impotence, not being able to solve anything, or to fix a problem, not knowing, not seeing, not being able to grasp a presence, for me art is a lack of power.

As the viewer looks at my work—whether it is chairs slowly descending from the Palace of Justice or a hollowed table filled with concrete—he or she feels this absence. The viewer is left with the impossibility of seeing which brings about the sensation of proximity—almost a presence and yet only absence.

My research has always led me to cases where the victim is persecuted beyond the possibility of self-defense. The victim has no defense in language, because the possibility of an apology is ruled out. So the victim becomes a solitary being for whom the mediation of language is not possible anymore. Consequently, there is no one the victim can talk to; no one would listen to him. There is just silence. Silence as a sign of solitude

I focus on political violence. Violence that is exerted against people who are invisible. There are always plenty of political, historical or personal reasons that motivate those that wish to kill, that declare entire civilian populations as invisible ones, as military targets, so they won’t see the individuals who suffer and can center their attention on the historical reason that justifies and legitimates their killings.

As a sculptor I see myself as a crossing point. I see myself as the terrain where the tragic experience of the victims of violence, the material traces left in objects, and some contemporary thinking, meet. To begin a piece, there is first of all a testimony. Then comes the material object, that has traces of every day life, and my intuition is guided by the reading of a thinker— many authors accompany me in silent collaboration.

The first conscious decision I make as an artist is to be immersed in a world where contemplation, distance and indifference are not possible. I decided to live in Colombia, a country at war. I believe that in order to comprehend our situation, our reality, it is not enough to define it or analyze it from a comfortable distance. It is essential to find ourselves in an sensible disposition towards that reality. To think a specific reality is no longer to contemplate it, but to commit oneself to it as the Philosopher Emmanuel Levinas wrote: “To be engulfed by that which one thinks, to be involved, this is the dramatic event of-being-in-the-world”. Therefore, I decided to be involved in the world of tragedy, the world of political violence.

My task as an artist is to make sense out of brutal facts. My work is an attempt to make violent reality intelligible—needless to say that a lifetime is not enough for such a task-. In the third world we are well aware that human beings do not triumph over external reality, we must produce meaning out of the tensions and chaos generated by our harsh conditions. Making art is a way of understanding, a way of comprehending reality. It is because human actions can become intelligible or have been rendered intelligible, that there is humanity.

Searching for humanity, searching for what is purely human in the middle of inhuman acts and inhuman conditions is what has guided my work. But, what is that element that we can identified as purely human? Where can we find it? I found an answer to these questions in the writings of the philosopher Franz Rosenzweig. He explains that what is purely human, is what is equal in all of us, and this purely human element is awakened in tragedy.

The common element in all of us is humanness, the human element equal in all of us, is not to be found in the peculiarities or in the personality of the individual, nor in race, religion or cultural differences. It is found in the self, the self within man, is what is mute and universal—the self as the expression of the human condition.

Rosenzweig said the hero of Greek tragedy embodies the solitary self, cut off from all relations to the world and his destiny is marked by two fundamental experiences: the encounter with Eros and the encounter with death or Tanathos.

The tragic hero awakens himself in Eros and accomplishes himself in his encounter with death. Death is silence, the impossibility of dialogue. Art is communication without words; art is silence.

Art is also mediation; and therefore it enables a self enclosed in his own tragedy to awaken another self, who is just as solitary. Art is the awakening of the human as tragic solitude: as fear and pity. Fear and compassion are the only feelings capable of confronting and breaking egoism, capable of awakening solidarity among human being.

As we see, art does not create a direct and true communication as language does, but nevertheless it awakens, outside the boundaries of time, an ephemeral community. This is why I feel it is so important to accompany the community of disappeared ones by making public the silence and private pain of each family. Through art I am trying to take this problem into the realm of the public, transforming an individual tragedy into a social phenomenon. I am attempting to form an even more ephemeral community, one that takes place during the brief moment the viewer contemplates in silence the work of art. It happens when the interrupted life of the victim—present in the art work—reaches out to find the memories of pain inscribed in each viewer’s memory.

The historical existence of man has always been of interest to artists because it is dramatic. Once again, Emmanuel Levinas gives us a perfect example: “Comedy begins with the simplest of our movements, each of which carries with it an inevitable awkwardness. In putting out the hand to approach a chair, I have torn the sleeve of my jacket, I have scratched the floor, and I have dropped the ash of my cigarette. In doing that which I want to do, I have done so many things I did not want to do. The act has not been pure, for I have left some traces. When the awkwardness of the act turns against the goal searched, we are at the height of tragedy.”

What is important about this passage is that it emphasizes that our knowledge and our mastery of reality, through consciousness, does not exhaust our relation with reality; it goes far beyond consciousness. Knowledge and control are rather precarious tools to deal with reality. Both comedy and tragedy are always present in our lives—as is the case daily in Colombia. One can quickly turn into the other.

I would like to think of this aspect from Levinas’ point of view. When we neglect a person, when we decide not to see his face, not to recognize the totality of a life, not to hear and not to speak to a person, we do this it in order to neglect and negate him. Partial negation is the beginning of violence.

Levinas points out that: “Partial negation is violence because it denies the independence of a person: Not to see the face of the other implies to negate his existence.” The Greek term Prosopon=face etymologically means, “What stands before the eyes, what gives itself to be seen.”

To see the one that is different with indifference is to look at a person as we look at objects—with the same indifference that we gaze at an object that we own; we look on with indifference because we own it, but in contrast we look with great interest at the objects we desire. When someone belongs to me as an object, I can deny his or her existence. When a person is seen as an instrument, a tool, just a means, his life is also an end to fulfill political purposes.

The person that is considered utterly different, the other, whose negation announces his murder, is the sole being that I wish to kill. No one wishes to kill someone that is considered his equal.

Killing is the manifestation of absolute power. And, there is nothing art can do against absolute power. When facing absolute power, we can say that art is useless, impotent in many aspects. But, even if it sounds like a contradiction, it has the tremendous power to bring back into the realm of humanity, the life that have been desecrated. That is why on November 6 and 7, 18 years after the destruction of memory, I chose to remember through my art.

Making art implies respect for the aesthetic view; it implies paying attention to every single detail of life. When I begin a piece I try to understand the victims of violence in the framework of his own history, his surroundings, his family and habits. At that point, the other, the utterly different, becomes a human being in the splendor of a complete life.

What my work tries to present is the fact that the past cannot be recuperated by representation, even if we use memory or history. There is no aesthetic redemption. In my work, I try in vain to recuperate the irreversible. It is an attempt to synchronize different times; but we know there is no common measure between the past and the present.

When we see a trace, the first thing we know is that someone has already passed. A trace is what is utterly past. What is irreversible, a trace is what signifies without making appearance. Through a trace, we establish a relationship with an irreversible past.

In any given image or in a given object there is the absent content of previous events that each single object carries. Any object, a shoe, a table, or a door carries certain intelligibility that adds meaning to the piece I make. Each object has been invested with memory.

Every object, in consequence, is invested with meaning. I look carefully for the meaning inscribed in each object. And my work simply tries to enhance it, to make it more evident.

Objects, like words, have to be placed in the proper context to be understood. They have to be connected with something that already happened, they have to be connected to history. The identity of things bears the identity of their history.

Just like language, experience does not appear to be made up of isolated elements. One cannot present an isolated image in a space on its own and hope it has a meaning by itself. Images signify on the basis of the world that they refer to, and on the confrontation of the position of the viewer with the position of the artist. I think the meaning of a work of art arises in the confrontation of these different worlds: the world of the victim, my own world, and the world of the viewer.

Man has the need to draw from the past criteria to act in the present. When man does not understand his past, his own history, he is deprived of reference points, and finds himself suspended between a past that is perceived as an accumulation of incompressible events, and a future that he can not possess. Therefore it seems like an abyss in front of him. The past is the only place where we can find both our origins and our destiny.

Doris Salcedo, an internationally renowned artist from Colombia whose work addresses issues of violence and holocaust, was a Visiting Scholar/Artist at the Center for the Study of World Religions at the Harvard Divinity School in 2002.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter

This is a celebratory issue of ReVista. Throughout Latin America, LGBTQ+ anti-discrimination laws have been passed or strengthened.

Editor’s Letter: Colombia

When I first started working on this ReVista issue on Colombia, I thought of dedicating it to the memory of someone who had died. Murdered newspaper editor Guillermo Cano had been my entrée into Colombia when I won an Inter American…

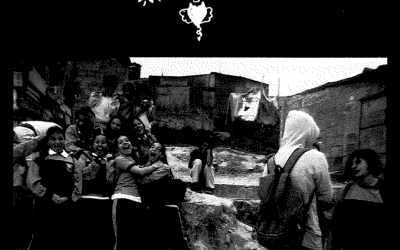

Photoessay: Shooting for Peace

Photoessay: Shooting for PeacePhotographs By The Children of The Shooting For Peace Project As this special issue of Revista highlights, Colombia’s degenerating predicament is a complex one, which needs to be looked at from new perspectives. Disparando Cámaras para la...