Bogotá Libraries

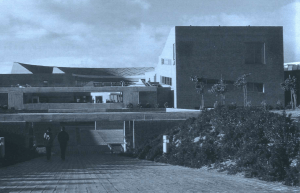

The outside of Barco library. Photo courtesy of T. Luke Young.

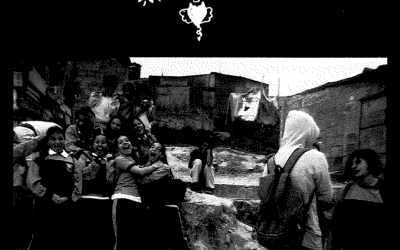

Last year, 9-year-old Jonathan Huertas and his three younger siblings spent their vacation indoors watching television—their mother was too afraid to let them play in the streets of their impoverished Bogotá neighborhood.

This year, instead of playing with their soccer ball on the dirt floors of their one-room house, or watching TV, the brothers spent every day in the library, a modern temple of culture. “Coming here is the best part of the day,” said Jonathan while he played chess and waited for his turn to use the computer — which he mastered fast, considering that he had never before had access to one. Nearby, Andres, his 8-year-old brother, read a lavishly designed children’s book out loud while his mother discreetly breast-fed her baby daughter in a window seat in a room full of light. Boys and girls talked about chess, computers and over all this, you could hear the whispers of the little ones who where softly reading their first words on whale or bear-shaped giant seat cushions. “The kids are happier here, they do whatever I say so they can come here as soon as possible,” said their mother, Luz María, who occasionally works as a maid to provide her family with extra income. Her husband sells wood knick-knacks on the streets for a living. There is not a single book in the house.

During the inauguration of the $10 million library. Bogota mayor Antanas Mockus declared, “Here there is a conflict that the protagonists say is caused by social injustice. Public projects like these generate equality. The books are arms that open the way.” The El Tintal library, one of three recently opened in poor and middle-class Bogotá neighborhoods, is part of the city government’s ambitious plan to improve urban life and encourage education and outdoor activity. The neighborhood associations are requesting activities, and there’s a group called “youth in action” and another called “grandparents’ corner,” not to mention opera performances, movie programs and workshops in computers and theatre. City Hall expects the three new libraries to be receiving 12,000 visitors daily this year. A fourth library, the main one in the city, already receives 9,000 visitors a day, more than the National Library of Paris or the main public library in New York City.

“I see the library as a piece of a jigsaw puzzle showing a different way of life, one more civilized where what counts is to read, to be outdoors — not to buy and have material things”, said Enrique Peñalosa, the former mayor of Bogotá who envisioned and constructed the libraries. Peñalosa, who left office a year ago, and Mockus are considered the leaders behind an incredible transformation of the city. The results are even more impressive given the country’s backdrop of a violent rebel conflict. Peñalosa said he insisted that the buildings, constructed by some of the best architects in the country, be spectacular urban icons, just like the cathedrals of the Middle Ages — and definitely more aesthetically pleasing and welcoming than shopping malls. “There was an emphasis on not only that the libraries were functional, but also that they had to be majestic, in homage to every child, every citizen who would enter there,” said Peñalosa, now a visiting scholar at New York University.

Bogota’s leaders, however, realize they’re facing an uphill battle. After all, it is the capital of Latin America’s only country in the middle of a war. And new parks and libraries can only go so far toward solving the country’s woes. In Bogota, an average of 41 people seeking refuge arrive in the city every day, fleeing the civil war simmering in the countryside. In every corner of the city there are displaced people carrying heart-breaking banners asking for money, with several children at their side. Terrorism showed its face in a deadly attack on February 7 that killed 36 people in an exclusive social club in northern Bogotá— evidence that the war, largely fought in rural areas, is creeping into Colombia’s cities. But still, Bogota’s turnaround is impressive. Murder rates have consistently gone down to levels below other Latin American capitals. Also, the quality of life—if not the average income—has improved dramatically; as a result, the United Nations has begun to export the Bogota model to other third-world cities.

Bogotá’s network of libraries has received international recognition. Last year they won the Access to Learning Award from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which granted them one million dollars to be used to improve the computer network and to fund programs in computer training. “Bogota’s new libraries match up with the best in the world, meeting community demands and providing excellent access to information and materials,” said Barbara J. Ford, director of the Mortenson Center for International Library Programs at the University of Illinois. “With the commitment we have seen, they are on the way to developing a network of strong libraries.” Miguel Angel Clavijo, director of the library in Jonathan’s neighborhood, said he’s had no trouble with violence since the library opened in mid-2001. “Maybe it’s the combination of beauty and functionality … that has prevented any problems,” he said.

City Hall expects that, by the end of the year, the three new libraries will be receiving 12,000 visitors a day. A fourth library, the main one in the city, already receives 9,000 visitors a day, more than the National Library of Paris or the main public library in New York City. The library frequented by Jonathan, which sits on top of what used to be a garbage recycling plant, draws more than readers. It has become a neighborhood meeting place. While Jonathan’s mother chats with another mother about the difficulties of breast-feeding, two men talk in the corner about their troubles finding a job. Jonathan and Andrés meet friends and cousins. But above all, the library provides support and the new civic environment necessary for children with limited resources to blossom and perhaps become the city’s next leaders. “In a few years, we will have the next (Colombian Nobel laureate) Gabriel Garcia Marquez coming out of these libraries,” Peñalosa said. “But over all, happier children just make better societies.” Jonathan might have the last say. Everyday, the eager nine-year-old begs his mother to take him the four blocks from his two-room home to the new El Tintal library. It is too dangerous, his mother believes, to walk alone.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter

This is a celebratory issue of ReVista. Throughout Latin America, LGBTQ+ anti-discrimination laws have been passed or strengthened.

Editor’s Letter: Colombia

When I first started working on this ReVista issue on Colombia, I thought of dedicating it to the memory of someone who had died. Murdered newspaper editor Guillermo Cano had been my entrée into Colombia when I won an Inter American…

Photoessay: Shooting for Peace

Photoessay: Shooting for PeacePhotographs By The Children of The Shooting For Peace Project As this special issue of Revista highlights, Colombia’s degenerating predicament is a complex one, which needs to be looked at from new perspectives. Disparando Cámaras para la...