A Life of Art

Searching for Peace

- Ivonne A-Baki, Verde Amazonia.

- Ivonne A-Baki, Social Injustice.

Art is a very enhanced form of expression: through it, the artist captivates its public through the senses, but also conveys a message that appeals to the mind. Art is therefore a means of communication, and communication holds the key to conflict resolution.

What is the relation between art and conflict resolution? I can only refer to my personal experience. My artistic work has always been the resolution of an inner conflict, a peaceful one but intense nonetheless. On the other hand, you know that sometimes diplomacy, which is just formal government efforts at conflict resolution, is called an art, and I would venture to say it is the art of the improbable. So there’s always been a connection between the two that I can now experience first-hand as the Ambassador of Ecuador to the United States who is also an artist, or the other way around. To me, the link goes deeper than formalities; in my personal experience, the two have been intertwined.

Both my passion for art and my search for peace grew out of my experience in Lebanon, while I was raising a family in the midst of the war.

Perhaps it was the impending sense of doom, the anguish of a mother fearing the ultimate loss of a child, or the sleepless nights as war raged on, that made me realize the value of peace and the need to devote one’s life, if necessary, to achieve it. I dreamt of the simple, precious things in life that I could not entirely enjoy, and peace became almost an obsession, a life-defining objective.

I realized that I could neither let myself become a helpless victim of tragic circumstances nor another link in a vicious cycle of hate and destruction. There had to be another way, one that would lay the ground for a permanent peace-and peace of mind.

I took a hard look at my reaction: there was nothing extraordinary in my aspiration, so it had to be shared, at some level, by everyone else. If war is never unavoidable, then why did politicians insist on escalating confrontation, rather than defusing it and promoting understanding?

I felt that the cause of peace was one that should have universal support, despite strong differences of interests and perceptions. Yet, despite numerous proclamations in favor of peace, action did not follow discourse -and the price paid was very high.

Whatever the reasons for the apparent deadlock, I perceived that at the grassroots level there was a genuine desire to lead peaceful lives, but years of conflict had left scars and, perhaps even more troubling for the prospects of peace, a complete lack of direct communication. How could this barrier come down, when every gesture from the opposite side was regarded with contempt and suspicion?

Almost surreptitiously, the answer came to me disguised as a hobby. I had started painting as a way to maintain my sanity in a senseless war, and the levity of art in such grave circumstances helped me relax and gain new perspectives on almost everything. Soon, I discovered the power of art. As an artist, I realized I was free to express my thoughts and emotions, even those that I could not voice as a woman in the Middle East.

People of all walks of life and from every background appreciated my paintings and understood my message, although I am afraid many would not have let me utter a word on the issue of women’s rights in a more conventional environment. As an artist, they even asked me to interpret the paintings and elaborate on my message! I also noticed that people from Europe or America could appreciate the paintings and somehow relate to them, despite having no experience in the Middle East.

Later on, I developed my artwork further in France, not because of the extraordinary architecture of Paris, the art-filled museums and galleries or even the classes at La Sorbonne, but because I embraced my inner emotions and was able to pour them onto a canvas with more precision. My art still reflected my convictions and sent a strong message about women’s empowerment, but I felt that my impact was limited in the area I most coveted: conflict resolution.

So, just as I had gone to France to develop artistically, I went to learn from the best about conflict resolution: Harvard University. At the JFK School of Government, all my instinctive ideas for conflict resolution found a theoretical framework and my approach to art and conflict resolution, to my surprise, was not shunned but rather very much well received.

Although academic life was very rewarding, I kept pushing for a more practical involvement in conflict resolution. My objective has always been working for peace, not learning about it. As a result, I became more actively involved in a non-official capacity in several conflicts in which Harvard played a “facilitating” role.

Perhaps the most important one was the Ecuador-Peru peace process and the encounters between representatives of civil society of both countries. True, there was a breakthrough after the Cenepa confrontation in 1995 that opened the doors for the official negotiations, as well as for increased participation in non-official encounters (previously, it could have been much harder to engage some high level participants in an exercise regarded as futile if no official negotiations were possible).

In any event, those initial encounters confirmed my perception that we could get along fine, just as long as we were careful to generate some confidence and establish a rapport in the first contacts before discussing contentious issues. The important thing was to keep the lines of communication open. A good way to let the guard down and establish contact always seemed to be art, which reinforced my deeply held convictions.

I painted a series dedicated to peace between Ecuador and Peru entitled “Beyond Boundaries”, and of course their appreciation always prompted the general acclamation of peace as a common goal. I knew then that we could work together to secure a lasting peace.

As the network of participants expanded, it grew to include personalities in both countries that were connected to or would later become policy-makers. However, by that time our dialogue had transcended entrenched official positions Officials; we had already established personal relationships and built the confidence that would be needed for the final stages of the negotiations.

I personally became a more active participant in the final stages of the process, and it was clear that we benefited from our previous informal contacts. The process itself was exhausting, as it needed to be inclusive, at least in Ecuador, in order to prevent representative groups within society from walking away or resorting to the old habits of demonizing the peace process.

There were certainly tense moments in the negotiations, particularly as the most sensitive issues were intentionally left for the last phase, and by then there was a growing sense of impatience. It was in those moments that our personal relationships and even friendships forged in both non-official encounters and official negotiations would prove essential. We were sensitive to each other’s constraints and political realities and could be confident that we were all truly committed to peace.

Finally, one of the most intractable disputes in the Western Hemisphere was solved peacefully through negotiations. The Peace Accords were signed in October 1998. Since then, trade between Ecuador and Peru has blossomed, and there is increasing cooperation at every level. It is worth noting that despite some political turmoil, not one significant party from either country has rejected the Accords.

As Ambassador of Ecuador to the United States, I am now officially trying to solve conflicts, fortunately always peaceful ones. I am sometimes struck by the question: How can I find time for my art, in the busy schedule of an Ambassador? The truth is that although I haven’t really had time to paint, art for me is not an occupation but a dimension. It defines me and permeates to all my activities, so no matter how long it takes me to paint again (and I keep promising it will be soon), I remain an artist.

But I have deviated from the topic of this article, and perhaps spoken too much about my life. Please do not take this as the proverbial modesty of all artists; my intention has been to illustrate the best way I can how I have felt and lived the connection between art and conflict resolution.

My experience has led me to conclude that those inclined to appreciate art can do so regardless of the artist’s background, even if they don’t agree entirely with the message conveyed. I sensed in a personal way that art could spread a message, even a revolutionary one, without the slightest threat of violence, for people will very seldom reject it entirely. At most, they will not be touched by the artistic work. Art is an area usually considered “harmless” by traditional politicians and “hawks”: initiatives for cultural and artistic exchange are welcome, just as political contact is disavowed,I have found. But cultural exchange breeds direct communication among members of the civil society, which in turn gives way to a wider dialogue. Invariably, more communication leads to a better understanding and the realization that people share some basic values and have common goals they can build upon to solve their conflicts.

There is, however, much more to conflict resolution, and the process could falter at any time. Nevertheless, I do believe that art and cultural exchange could jump-start a process that requires skillful negotiators and a cooperative approach to achieve its ultimate goal. Art also creates the right atmosphere to foster the confidence and goodwill needed to prevail in the often tortuous and extenuating negotiating process.

My experience in the Ecuador-Peru peace negotiations validated my views, and was an extremely rewarding exercise. Yet there is much more that remains to be done in the conflict resolution arena, and I trust more and more people will become engaged in the search for peace.

I hope that the link between art and conflict resolution will become ever more evident, and someday we will all be able to enjoy art in a peaceful environment.

Winter/Spring 2001

Ivonne A-Baki, Ambassador of Ecuador to the United States since 1998, is an artist who has had major exhibitions in Ecuador, Lebanon, France, and the United States. She was an Edward S. Mason Fellow and holds a Master in Public Policy from the John F. Kennedy School of Government (1993), and since 1990 has been an Artist-in-Residence at Dudley House, Harvard University.

Related Articles

Guatemala Diary

In a deeply personal way, I feel like I am home again. Of all the places I have visited, Guatemala is the country I love and feel closest to. Certainly the most impressive aspect is the persevering Mayan people, who endured a 30-year civil war…

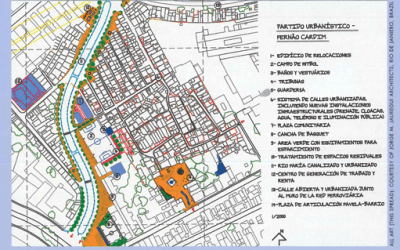

From Favela to Bairro

The Brazilian firm of Jorge Mario J¡uregui Architects is the first Latin American recipient of the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Veronica Rudge Green Award in Urban Design. The award…

Exploring New Horizons in Latin American Contemporary Art

When I first traveled to Peru by boat with my family fifty years ago, the country seemed as far away from Argentina as Boston from Buenos Aires. My husband had been sent there by W.R…