An Ecologist in Cuba

Citrus and Camaraderie

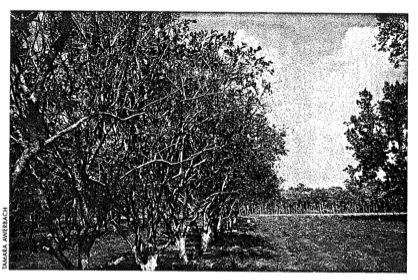

Cuban citrus fields are the subject of a long-term study.

On a snowy afternoon in February, we embarked on an Iliushin airplane that would take Richard Levins and myself from Montreal to Havana. At first I was apprehensive about getting on an old Russian-made airplane. However, after a few minutes into the surprisingly pleasant flight and Richard’s reassurances, I was no longer nervous about my first trip to Cuba.

My colleague Richard Levins, a professor of population sciences at the Harvard School of Public Health, has been making his way to the tropical island for the last 33 years as an advisor to the Cuban government on scientific projects in ecology, agriculture, and public health. He always had told me how the Cubans, in the face of limited resources, use vision, creativity, and a common ideology to provide answers to scientific problems that wealthy countries usually approach with an abundance of money. Richard now added that careful plane maintenance, despite limited resources, was a priority because of the Cuban emphasis on tourism; the smooth ride later became my private metaphor for our two-week, carefully-planned stay in Cuba.

This visit, however, was different for Richard than previous ones, because we were a team. I came along to provide additional support to ongoing projects and to start a collaborative relationship between the Human Ecology group at the Harvard School of Public Health and Cuban Institutions. And Richard Levins was to give a plenary speech in a conference organized by the Institute of Philosophy in celebration of the Communist Manifesto’s 150th anniversary. We would spend the first week with the National Institute for Research in Citrus and other fruits, and the second with the Faculty of Mathematics at the University of Havana.

Our collaboration with researchers in Cuba was aimed at understanding why a scale insect present on Cuban citrus is not a serious pest in Cuba but damaging elsewhere. Richard and I have been trying to answer this question by analyzing data about insect scales and their natural enemies dwelling on citrus leaves. Cuban citrus workers had dutifully counted the scales on various trees twice a month for two years and kept a careful record.

As I was sitting the first day in the Citrus Institute conference room with the citrus researchers, I was impressed by the informal productive discussions and the cooperative environment. Richard was the only man in the room. Later, I discovered that the leaders of the Institute and its subdivisions are mostly women. We also learned that instead of fixed departments, there are flexible research groups. Each person may belong to several such groups, leading one and being a participant in others. Some groups are long-term and others are created and dissolved, according to research needs. The Institute carries out research and then makes practical recommendations to farms. It has been a pioneer in the concept of mixed urban, suburban, and rural agriculture. It is on the forefront in graded transition to ecological and organic agriculture, as well as polyculture in fruit growing. Richard Levins has been a long-time participant and observer in this process, and his contributions carry significant weight, the Cubans told me.

To witness progress in these areas, we made a field trip to the Granja, the site of our collaborative research on pest dynamics of citrus. On the way, we stopped at the home of a Cuban colleague who was home sick and unable to participate in the excursion. Magda was a long-time friend and colleague of Richard’s, and I asked him if it wasn’t a bother to share his friends with me when there was so much catching up on old times to do. “I love seeing Cuba through your first-time eyes,” he replied, and we entered into a beautiful Spanish-style house with high ceilings and colorful tile floors. A picture of Che Guevara was the only decoration on the walls. We were immediately offered Cuban coffee, prepared by Magda’s son, whose family lives with her. Magda told us that in Cuba, there is a shortage of housing, and it is quite common for three generations to share the living space; the company of her son, daughter-in-law, and granddaughter were a great source of joy, she said.

After an hour, much too short for Richard and Magda to catch up on a year of life, we set out on the road to the Granja, stopping at an ice cream kiosk along the way. I licked my delicious vanilla ice cream with a certain amount of guilt, wondering why it was so popular to get ice cream when milk was so scarce in grocery stores. Indeed, reasonably-priced milk could only be obtained for children under five. As we approached the Granja, we could smell the sharp fragrance of citrus flowers; and arriving, we saw the experimental polycultures of citrus mixed in with rows of cassava, soybeans, and tomatoes. As we looked at the orange leaves, the scale insects, the object of our long-term study, became apparent as tiny brown spots attached here and there to the surfaces.

Back at the Institute we discussed the results of our studies, explaining why the scale is not a problem in Cuban citrus despite the fact that no interventions had been introduced. An analysis of the data showed that the scale insect is rare in early spring and only increases after the first flush of new citrus leaves. However, parasitic fungi appear in the fall and a wasp in early winter, resulting in a crash of the scale population. These natural enemies prefer different strata of the tree and different leaf surfaces so that the scale is parasitized in all parts of the tree. The seasonal buildup of natural enemies regulates the population so that although there is variation of two orders of magnitude during the year, the population remains in check from year to year. We learned that perhaps the best control strategy is not to intervene.

Richard and I shared these results with colleagues in all fields of life sciences who participated in the bio-mathematics course we conducted at the University of Havana during our second week in Cuba. The course was aimed at promoting theoretical research in biology and presented methods of qualitative mathematical analysis with special application to the coexistence of species, management of pests, and the dynamics of epidemics. We found even more collaborators through this course, and linked Cuban investigators to each other. We are looking forward to returning in March, 1999, with further investigations cosponsored by the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies.

Fall 1998

Tamara Awerbuch is a member of the New Disease Working Group at the Department of Population and International Health and Co-Chair of the Committee of Bio-Statistics and Public Health Mathematics at the Harvard School of Public Health. She is also a lecturer at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute.

Related Articles

Caballero wins Colombia’s top journalism prize

Building on work she started at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, investigative journalist Maria Cristina Caballero has won Colombia’s top journalism prize…

Between Vengeance and Forgiveness

At the close of this century of death camps, killings fields and desaparecidos, there is perhaps no more urgent question than the one raised in Martha Minow’s useful new book: Can societies…

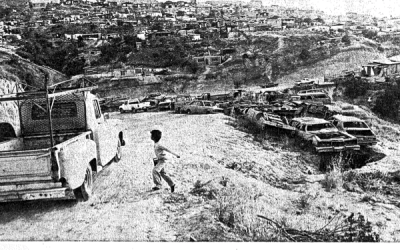

The Environment in Latin America

This issue of the DRCLAS NEWS deals with some of the environmental problems of Latin America, one of the priorities of the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies…