A History of Violence, Not a Culture of Violence

Finding Historical Consciousness in Guatemala

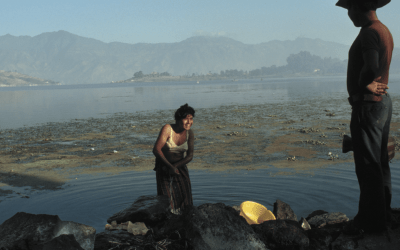

Guatemala has earned the unfortunate name of “Killer’s Paradise.” Photo by Carlos Sebastian/Prensa Libre

Kendyl tucks her sleeve over her hand and wipes the bus window. “Why are you so interested in war memories?” she asks, catching me off guard. “If you are interested in violence, you don’t have to go into the past to find it. Violence is everywhere.” I hesitate over my response. Why does insisting on remembering the war suddenly feel arrogant?

Outside the window, women roll barrels of corn on stones rough as their heels. “What’s so bad about forgetting? What’s wrong with not wanting your kids to know the fear you lived, to want a life for them where they aren’t held responsible for the past?” Maybe she has a point. Maybe selective forgetting is a conscious choice passed on to the postwar generation—but with what consequences?

In the aftermath of ethnic violence, historical consciousness can frame critiques of ongoing systems that reinforce social inequalities and suffering. But there is a history of silence here. And with the emergence of new forms of “postwar” violence, the memory of La Violencia, the thirty-six year civil war and genocide, has been pushed to the middle pages of newspapers or reframed in Plexiglas posters claiming peace and multiculturalism at city bus stops. School textbooks mask this era of internal violence as a conflict between “two devils,” as if the state and guerrilla armies played equal roles. Before coming to Guatemala, I had wondered what kinds of memories would surface from a submerged recent past. As contemporary violence escalates, my perceptions have turned like marbles on a wood floor.

Since that warm day on the bus with Kendyl, I have struggled to find out why studies of past violence warrant a place alongside discussions of present-day violence. Hundreds of Guatemalans have helped me see the past and present through varying prisms of memory and meaning. Guatemalan activists have insisted on critical historical consciousness as a postwar imperative, exposing to me the dialectics between silence and violence, history and culture, and impunity and empowerment.

Raúl, who asked that his name not be published for security reasons, for example, tells me about ongoing campaigns to raise consciousness about impunity for wartime crimes in the Hijos por la Identidad y Justicia contra el Olvido y el Silencio (HIJOS) office. When I ask whether HIJOS activism now extends to contemporary crime, he says yes and no, describing the topology of past and present violence like the twist of a Mobius strip. He explains that the same people who orchestrated past genocides still operate in unconcealed political and military positions of power, or more discreetly in the shadows of paramilitary forces, death squads or organized crime. “There are clear examples that the military still presides in Guatemala,” he says. “Ríos Montt continued his power in Congress; death squads still exist, eliminating hundreds of young people; social movements are repressed… forced disappearances against peasants or indigenous people also continue to exist. It’s a violence or repression that we can’t view as new—rather, it’s a result of the political repression that was used in the war against our parents.” I nod, watching Raúl’s eyes flicker over the poster of hundreds of faces of the disappeared, their photographs lined up like mug shots. “The mechanisms that made the genocide possible are the same mechanisms of control and repression, now much stronger and more dangerous, because today we can no longer identify only one group responsible.” This web of simultaneous forces creates a more dangerous contemporary network. Many of these dark forces collaborate, strengthen, and protect one another—or compete for power—thereby escalating the number of victims, he says. His critique emphasizes the connections between past and present violence, identifying a commonality between actors, modes of violence, and impunity.

When Guillermo, who also asked that his last name not be published for security reasons, and I go for after-dinner walks to the nearby soccer field, no more than 200 feet from his home, his parents await our return nervously. Relative proximity does not imply safety. “That gate doesn’t make you safe,” they warn me. Even living in a gated community with 24-hour security guards, as does one out of every ten families in Guatemala City, does not guarantee protection from the violence that defines present-day, “postwar” Guatemala. Guillermo’s backpack rattles as he comes through the open hallway, a dead giveaway. His parents unzip his bag in a panic, searching for cans of spray-paint that he uses for poverty, drug, and violence awareness messages, desperate words on the walls of buildings. They argue about the kind of person Guillermo is becoming, someone who vandalizes buildings, a common delinquent with secrets. He does not tell them the truth, that their sadness is heavier than the oak furniture that fills their dead daughter’s preserved bedroom. She left one night and never came back. Her body was found less than two miles from their house.

Legal impunity for the criminals of the past has engendered a “culture of impunity” that penetrates Guatemalans’ everyday lives, diminishing trust in the government, justice system, and the role of seemingly powerless citizens, conditions that have earned Guatemala the name “Killer’s Paradise.” For many, civic impotence leads to apathy toward violence, exhibiting a resignation that implies, past or present, you’re not safe here, because Guatemala is Guatemala. All over the country I hear the same narrative from adults and adolescents, Mayans and ladinos: Guatemala is a violent country with a violent culture. They cite the war and present-day violence as two examples from a historical continuum of turmoil, meaning that a history of violence implies a “culture of violence.”

The official rationale for much contemporary crime is that learned violence is an unfortunate social remnant of past violence, notably the recent civil war. Though thousands of young people were forcibly recruited into the state or guerrilla army and trained in methods of inflicting violence and invoking fear, the idea that contemporary crime can be so simply understood as a consequence of historical violence is misleading. Unlike Raúl, who holds powerful institutions and individuals responsible, many attribute Guatemala’s experience to an ingrained culture of violence. In this reading of history, though, power continuity and structural inequality go undetected. Like all “postwar” crime, socialized violence has been given room to fester because of conditions of impunity.

Jorge Velásquez enters the Ministerio Público investigator’s office after rescheduling his meeting for the fourth time. Once every week, Jorge dresses up in a suit, drives through Guatemala City traffic, pays a parking attendant, and waits in the public prosecutor’s office or his lawyer’s office or the human rights ombudsman’s office or some state institution to see whether they have made any progress on his daughter’s case. It has been three years since Claudina Isabel’s brutal rape and murder, but his devotion to her case is unwavering, even in the face of state ambivalence and outright resistance toward his pursuit of justice. Jorge begins, “I am not here to complain, but to request a change. I am here today, three years after my daughter’s death, and it is as if she died yesterday. I have been to meeting after meeting, and the case never moves forward.” Behind his glasses, tears gather in Jorge’s eyes.

The investigator listens with distanced composure. He leans over and adjusts his socks so that they rest evenly on his calves, then returns to Jorge. Jorge’s face is red and swollen, his shirt collar tight around his neck. He goes on. “There are six suspects, and none have been interrogated. There are mistakes in the forensic report. The case has not moved forward. The loss of a child is incomprehensible. No one’s stomach has been the same since Claudina Isabel was killed. They insulted my daughter’s character—her character! Do you know what the police said? The police said they thought she was a prostitute because she was wearing sandals. Do you know what it’s like to identify the body of your daughter? You are the third investigator to have this case in your hands. Every time I come in here looking for progress, I move backwards and have to start over. Ya no voy a ensuciar el nombre de mi hija.” Most victims of contemporary violence cannot do what Jorge does. They fear retribution, opting for silence as a mode of protection. They do not live near enough to the capital to register continuous complaints. They cannot afford to take time off work to pursue justice. They do not know the middle-class protocol required to be taken seriously. Though Jorge does not articulate his devotion to justice for these victims, he is simultaneously fighting for justice for past and present crimes by demanding an end to impunity, the salient connection between La Violencia and “postwar” violencia. He shoots the investigator a face stiff with rage. “Impunity was an invitation to kill my daughter.”

Lack of accountability for past and present violence has created an environment in which violence is permitted, if not provoked, by the implicit guarantee of impunity. And present crime often involves past criminals who have been granted legal amnesty. Fear of postwar violence, aggravated by impunity, may silence those who would otherwise make their memories known.

Postwar violence is also perhaps a consequence for a citizenry whose critical reckoning of the connection that its past has with its present has been silenced. The war is relegated to a history disconnected from the present. For many, the dangers of the present do not resonate with memories of the war. Postwar violence is dismissed as gang-related delinquency indicative of a “culture of violence,” even when crimes are noticeably politically motivated. The assertion about Guatemalan nature as inherently violent surrenders to discourses of power that situate contemporary violence as cultural rather than structurally caused, reinforced, and pardoned: “it negates the political character of the conflict and implies that there can be no political solution” (Victoria Sanford, “Learning to Kill by Proxy: Colombian Paramilitaries and the Legacy of Central American Death Squads, Contras, and Civil Patrols,” Social Justice 2003 p.15). This reductive excuse asserts that violence is endemic because it is intrinsic.

Guatemala’s national memory of La Violencia cannot be understood without recognizing its contemporary embeddedness in “postwar” violencia—violence provoked, protected, and perpetuated by impunity. The absence of critical analysis of ongoing violence is entrenched—not in the culture of Guatemalans, but in the sparse and sterile representations of the past by those in power. Despite its now leftist government, Guatemala’s Ministry of Education has yet to institute a history education that confronts the recent violent past. Perhaps the lack of critical inquiry into violence has contributed to a tolerance of violence. It also seems possible that the deficiency of critical historical consciousness is, in part, a consequence of postwar violence. In this context, it is no surprise that postwar crime overshadows the war.

Creating meaningful and sustainable peace requires critically confronting violent pasts: interrogating the conditions that allowed conflict to take hold, while holding individuals and institutions accountable for their actions. Critical historical consciousness of past violence has everything to do with understanding—and challenging—postwar violence in Guatemala.

Fall 2010 | Winter 2011, Volume X, Number 1

Related Articles

Guatemala: Editor’s Letter

The diminutive indigenous woman in her bright embroidered blouse waited proudly for her grandson to receive his engineering degree. His mother, also dressed in a traditional flowery blouse—a huipil, took photos with a top-of-the-line digital camera.

Making of the Modern: An Architectural Photoessay by Peter Giesemann

Making of the Modern An Architectural Photoessay by Peter Giesemann Fall 2010 | Winter 2011, Volume X, Number 1Related Articles

Increasing the Visibility of Guatemalan Immigrants

Guatemalans have been migrating to the United States in large numbers since the late 1970s, but were not highly visible to the U.S. public as Guatemalans. That changed on May 12, 2008, when agents of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) launched the largest single-site workplace raid against undocumented immigrant workers up to that time. As helicopters circled overhead, ICE agents rounded up and arrested …