Telling the Story

A Journey Back to Guatemala

When we finally pull into San Lucas Tolimán, after a winding drive through the Guatemalan highlands, I immediately notice the kids. Two small boys giggle as they roll motorbike tires down the road. A gaggle of schoolgirls in traditional fabrics walk linked arm-in-arm. A young girl holds an apple-cheeked baby. Boys play soccer in the dust of an abandoned store.

The children exude happiness everywhere. They are a testimony that life can be beautiful, even in the poorest settings. But under the surface, it only takes a scratch or two to uncover a sad history here. And it’s a bloody one.

I spent my own childhood in Guatemala City, a USAID (United States Agency for International Development) “brat.” I was totally unaware of the country’s history—even though it was then a daily reality for other children. I lived a carefree life, fairly oblivious to the violence—the last four years of a bloody war—just outside the spike-covered metal gate that surrounded our home. And so, 14 years later, I decided to return to my adopted homeland in an attempt to learn about the “real” Guatemala I was shielded from as a child.

My task at hand was to conduct a needs assessment in San Lucas Tolimán as part of a practicum for my master’s degree in Public Health at Harvard. I wanted to learn about the causes and experiences of mental distress in the community and what existing resources can be used to help ease suffering. Perhaps more importantly, however, I wanted to learn about and to tell the story of la violencia.

Nestled at the foot of the Tolimán volcano on the shores of Lake Atitlán, arguably the most beautiful lake in the world, San Lucas is a bustling town of roughly 15,000 people, surrounded by 22 small rural communities that are home to another 20,000. The Kakchiquel Maya, who have resided in the region for centuries, make up nearly 90 percent of the population.

This picturesque landscape was the site of some of the bloodiest atrocities committed during la violencia—the civil war in Guatemala that spanned over three decades. During this period, a vastly outnumbered guerilla force clashed with the military, which waged a bloody campaign against suspected “communist subversives.” The indigenous peoples of Guatemala, the objects of discrimination by the Spanish-descendant elite for centuries, were easy targets.

At war’s end, around 200,000 people (more than 80% of them Maya) had been killed, many in mass executions. Thousands more disappeared. The area surrounding Lake Atitlán was particularly hard hit. Encarnación “Chona” Ajcot, a Kakchiquel Mayan from San Lucas, recalls that guerrillas fighting against government soldiers would come into San Lucas offering money, houses and land to entice the Maya into joining them. “Instead of finding these things,” Chona told me, “the people found death.”

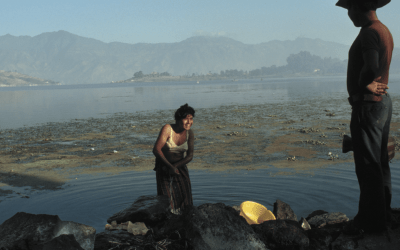

It is the women who keep things going in San Lucas, and the women who suffer the most. You can see it in Chona’s face and the faces of countless other women, young and old. My interviews reveal that the only outlet for expressing their distress is physical: what is known here as “an attack of the nerves.”

An “attack” happens when worry, sadness or fright—often specters of extreme poverty—weaken the nervous system, causing aches and pains and sometimes even diabetes and stroke. Treatments for “nerves” range from Tylenol to locally manufactured “neurotropics”—vitamins that are either injected or taken orally to “calm the nerves” and build immunity. Traditional herbal remedies are widely used, especially by those who cannot afford to pay for treatment.

Religion, including both Catholicism and evangelical movements, is another source of comfort. It is difficult to talk about San Lucas without mentioning the San Lucas Mission. Founded by the Franciscan order of the Catholic Church in 1584, the Mission is part of a long-standing Catholic tradition dating back to Friar Bartolomé de las Casas, who convinced the Spanish king to legally recognize Mayans as Spanish citizens and condemn mass slaughter. Much of the success of the church in Guatemala is attributed to its work in social justice, incorporating traditional Maya beliefs and practices and providing education in indigenous languages. Father Greg Schaffer, a diocesan priest from Minnesota, has led the San Lucas Mission since 1962.

Today Fr. Greg continues this humanitarian tradition through his commitment to liberation theology, a school of thought within Catholicism that defines the mission of the Church as bringing justice to the poor and oppressed (Preferential Option for the Poor).

“Fr. Greg helps people in need, regardless of their culture, race, sex, or religion,” says Chona, who has worked with him for decades. In 2007, he was awarded the Order of the Quetzal, the highest award bestowed by the Guatemalan president, for his commitment to the poor of San Lucas.

When Fr. Greg arrived, San Lucas was the poorest city in Guatemala. Land ownership was highly concentrated; only two percent of the population was literate. Over the years, he purchased land from plantation owners and returned it to the people. In Maya culture, land is identity and corn is everything. To them, corn grown on your own land is thought to taste better and be better for you. “Without tortillas we die,” says Chona. Since the 1960s, literacy levels in San Lucas have risen to 85 percent; parish scholarships have enabled many Maya children to pursue studies at universities and technical schools.

One of these children was Dr. Marcos Tun, the head of the parish clinic for the last 12 years. The first in his family to achieve an education of any kind, Dr. Tun returned to San Lucas after completing his medical training, despite offers to earn a much higher salary at a hospital in the city. “I wanted to give back to my community,” he tells me. As a local, “I know the community and so that helps me be able to find the best treatment for patients,” he says. However, this also comes with “responsibility: because I know a patient can’t afford the medicine he needs I have to find a solution. I can’t just assume they’ll work it out on their own.”

Despite these success stories, however, the big picture is less than rosy. Today Guatemala has the highest malnutrition rate in the western hemisphere (higher than Haiti, even) and poverty and socioeconomic disparities have remained unchanged.

As a guest at the parish for a month, I eat humble meals in the company of a seemingly unending influx of volunteer groups from the United States who spend a week working side-by-side with the locals on various hard-labor projects. It is heartening to see their cross-cultural interactions, but I can’t help but wonder: why aren’t there any Guatemalan volunteers?

Today I am lucky enough to have stumbled upon an impromptu talk on the history of San Lucas by Chona and Father Bill Sprigler, another Minnesotan priest returning to San Lucas for the first time since 1989. The talk quickly turns to la violencia. Chona lived la violencia; Father Bill experienced it in pieces.

Chona’s story begins in 1981 with the assassination of Father Stan Rother, a U.S. priest and good friend living in the nearby town of Santiago de Atitlán. Fr. Stan was conducting mass with several nuns from his parish when he spotted the military approaching. He told the nuns to go into his room and lock the door. As they hid, the nuns witnessed military troops beat Fr. Stan and shoot him in the head. “In that time you couldn’t help poor people, the Maya, because the military would accuse you of being part of the guerrillas,” says Chona.

Liberation theology, which incorporates Paulo Freire’s ‘concientization,’ “was perceived as communist,” Fr. Greg tells me afterwards. “Our own government vouched that this was an attempt at communist takeover.” The mission was constantly under surveillance with sermons monitored daily for any sign of subversion.

Fr. Greg and Chona were committed to helping people from the community accused by the military of being “subversives.” They would hide and smuggle people out of the region, including young orphans.

Chona’s husband worked at the parish, helping arrange land titles for community members. On December 1, 1981, a day she remembers as if it were yesterday, he disappeared. On his way to the city of Sololá to deal with paperwork, he was captured by the military. “We don’t know how they killed him or what they did with the body,” Chona says.

During the next year she and her three young children moved from house to house, staying with different relatives and friends for their own safety.

The nights, she says, were the hardest. “At night we were frightened, very frightened…the soldiers would come to your house to find you and kill you…always at night.”

“I am just one of many women, wives, mothers and grandmothers who suffered,” says Chona. “Those were very difficult times.”

It is hard to calculate the toll of la violencia in San Lucas. To give you some idea, all but three of the first graduating class of the parish school—around 20 students—were executed.

The violence and tragedy continue with major earthquakes and mudslides. Narcotrafficking and gang violence, as well as high rates of alcoholism and domestic violence, now plague Guatemala. In San Lucas, young gang members loiter by the lakefront at night. I’m told it’s unsafe to venture out after 9 p.m.

Here, as Fr. Bill notes, they live the mantra “keep your eyes on the sky.”

“One has to think about the good, the beautiful in life and not about the difficult things,” Chona tells me later.

The total destruction of social capital is one of the lasting legacies of la violencia. People were displaced, neighbor betrayed neighbor, and a generation was slaughtered. Now, trust is hard won in this community. Few people feel comfortable sharing their more intimate sorrows and fears.

Still, there are those who want, and need, to tell their stories.

Chona begins to weep after recounting the death of her husband. “We’ve covered enough,” Fr. Bill explains to the audience, himself overcome with emotion. “There are too many memories here.”

But Chona begins telling another story, about smuggling orphans out of Quiche. When she pauses to wipe her eyes, Fr. Bill gently urges: “We can stop. It’s very difficult.” “No,” Chona replies. “I want to tell the story, how it was.”

So much has changed in the last decade in Guatemala. Little by little the stories emerge, and the injustices are brought to light. Yet the small children I see laughing and playing on the church steps still face an uphill battle in a country that wants to forget their existence. Indigenous Guatemalans like Chona share the brave task of retelling the terror they faced during la violencia, but the same question remains: who will listen?

Fall 2010 | Winter 2011, Volume X, Number 1

Emily Sanders completed her Master of Science at Harvard School of Public Health. She has lived and worked throughout Latin America and is interested in health sector reform. She traveled to Guatemala in July 2009 with a DRCLAS summer research travel grant. Contact: ecsanders@gmail.com.

Related Articles

Guatemala: Editor’s Letter

The diminutive indigenous woman in her bright embroidered blouse waited proudly for her grandson to receive his engineering degree. His mother, also dressed in a traditional flowery blouse—a huipil, took photos with a top-of-the-line digital camera.

Making of the Modern: An Architectural Photoessay by Peter Giesemann

Making of the Modern An Architectural Photoessay by Peter Giesemann Fall 2010 | Winter 2011, Volume X, Number 1Related Articles

Increasing the Visibility of Guatemalan Immigrants

Guatemalans have been migrating to the United States in large numbers since the late 1970s, but were not highly visible to the U.S. public as Guatemalans. That changed on May 12, 2008, when agents of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) launched the largest single-site workplace raid against undocumented immigrant workers up to that time. As helicopters circled overhead, ICE agents rounded up and arrested …