A Medical Student Looks at Cuba

A Country of Contradictions

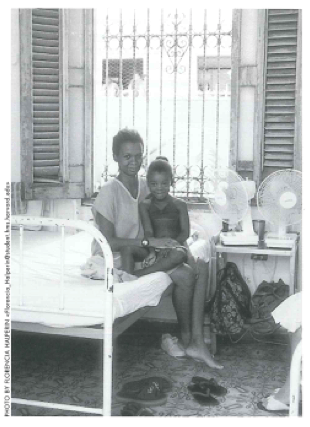

Mother and child in clinic

Fresh off the plane, and already my interest was piqued as we drove out of the airport in Havana. I had just finished my first year at Harvard Medical School, and was in Cuba with a group of students on a medical education program. I was intrigued by the Cubans who drove us that night to our destination in the western province of Pinar del Rio. To begin with, they all had names I had never heard of, as Spanish names: Ivan, Mariushka, Marleni (short for Marx Lenin)-they were all Russian names! Furthermore, both the van driver and his wife, who was along for the ride, spoke not only Spanish but also relatively good English, and they told me they had both been trained as engineers. I remember feeling puzzled to meet an engineer working as a hired driver, and this was only the first of many paradoxes I would find on this beautiful island. Indeed, if I can say one thing about Cuba after my month-long stay, it is that Cuba is a country of contradictions.

One of the most moving experiences of my life came a few days into my work with Sofía, the community doctor with whom I saw patients. Sofía and her husband, who have two small children, are both physicians. Sofía’s consultorio(medical office) occupies the first floor of her family home (all community doctors live in a similar setting). After six years of medical school and three years of service to the government as community physicians, Sofía and her husband each earn twenty dollars per month. Their house belongs to the government, their education and their children’s (including their textbooks!), as well as their health care, are absolutely free, and they get food rations from the government. As a family, they receive six pounds of sugar, eggs, rice, beans, milk, and one small bar of soap per month. They say that they are happy with their home, proud of their education and their health care system, but what they get to eat is not enough. If they want meat (or laundry detergent, or clothes) they have to purchase them at import prices similar to those we pay here in the United States. Forty dollars a month does not stretch very far for all of these things. As well educated as they are, this family cannot afford the luxury of toilet paper, and uses the day-old newspaper instead.

A few days after my arrival, Sofía invited me over for lunch, and although I was practically a stranger in their modest home, they treated me to a royal feast. They made a delicious stew, with beef; they bought pizza, and made batidos de mango (mango shakes) with fresh milk. I was overwhelmed by their generosity, and at the same time plagued with guilt as I sat consuming what was at least half their monthly salaries. This was my first heart-warming encounter with the Cuban spirit of brotherhood, and there would be many more: I discovered that Cubans have a gift for making people feel welcome and included. It still brings tears to my eyes to think that with so little, they offered me so much.

Cuban nature is open and inviting, generous and warm. And yet these very people have laws that prohibit them from visiting the establishments of their compatriots. When a group of us wanted to travel for a weekend to the lush park of Vií±ales with a Cuban medical student we befriended, we were stunned by the obstacles we encountered. Our driver, with his baby blue 1961 Chevy, and in desperate need of the few dollars we offered, could not bring our friend Miguel, because if he were stopped by the police with Cubans and Americans in his car, he would be fined a large sum. So Miguel rode the 20 miles on his old Russian bike. Moreover, most Cubans cannot eat out in restaurants or rent accommodations when they travel in part because they cannot afford it. But even if we wanted to pay for our friend, by law he is not allowed to eat, or even sit at the table, with tourists, and he is not allowed to sleep in the Cuban homes where we rented rooms. I could see in the eyes of the proprietors how deeply they regretted having to turn a fellow Cuban away, but if “el Inspector” (a neighborhood Party representative) discovered Miguel at a restaurant or in a rented room, they would be subject to hundreds of dollars in fines. Although the laws have been made under the pretext of preventing hustling and prostitution, I wondered if the hidden agenda was to prevent the exchange of ideas?

I am originally from Argentina, and in Argentina we know about political repression and persecution. We had totalitarian regimes, military coups, and even concentration camps until the 1980’s. My family fled when I was two because as Jewish doctors my parents were under threat. But in my simple scheme of right and wrong, it is easy to categorize what happened there. Universities and schools fell to pieces. People were tortured and murdered for their beliefs, or even for the sin of being listed in the address book of someone suspected of anti-government activism.

In contrast, I struggle with an image of Cuba where people are not free to tell their friends what they think, where people go hungry, where well educated, honest folk turn to illegal tourist activities because it is the only way to earn enough to clothe their children, and yet where every person has a home, every person is taught to read, is given some food, and has their medical needs met. Indeed, in Cuba, everyone has access to health care and there is one doctor in every neighborhood. Physicians are trained to emphasize prevention; their job includes visiting patients at home, and ensuring public health standards are met. For example, they verify that if animals are kept they are clean and separate, or that electrical outlets are covered if there are young children in the home. The infant mortality rate is one of the lowest in the world; Cuban children are vaccinated, and all women have access to regular Pap smears and mammograms.

My trip to Cuba made me appreciate the luxuries available to me in my daily life. It gave me a taste of what it was like for my parents to live under a totalitarian regime. In many ways I came to understand those who risk their lives every day to flee Cuba. Yet at the same time I was left in awe of their warm generosity, revolutionary idealism, and contagious cultural rhythm. I was moved by their commitment to provide housing and health care for all of its citizens, a principle that has not been adequately embraced in the United States, where homelessness is pervasive and there are more than 40 million people without health insurance. Cuba, for all its contradictions, has valuable lessons to teach even a rich and democratic country like our own.

Winter 2000

Florencia Halperin grew up in Argentina, Venezuela and Brookline, MA. She is currently a second year student at Harvard Medical School with a particular interest in issues of health in immigrant communities.

Related Articles

Isabelle DeSisto: Student Perspective

encountered the first obstacle of my trip to the Isla de la Juventud before I even left Havana. Since American credit cards don’t work in Cuba, I couldn’t buy my plane tickets online. But that…

Honoring Humanity: An “Interview” with Richard Mora

Mauricio Barragán Barajas: Why don’t we begin by having you introduce yourself? RM: Alright. I was born in East Los Angeles, and grew up in Cypress Park, a barrio in…

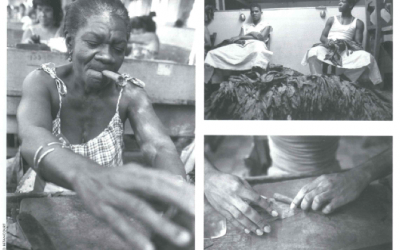

Tobacco and Sugar

“Tobacco and Sugar” is the course that focuses American literatures on the Caribbean, and that acknowledges the unavoidable importance of monocultures for cultural studies. Much of the…