A Monumental Battle for the Story of Texas

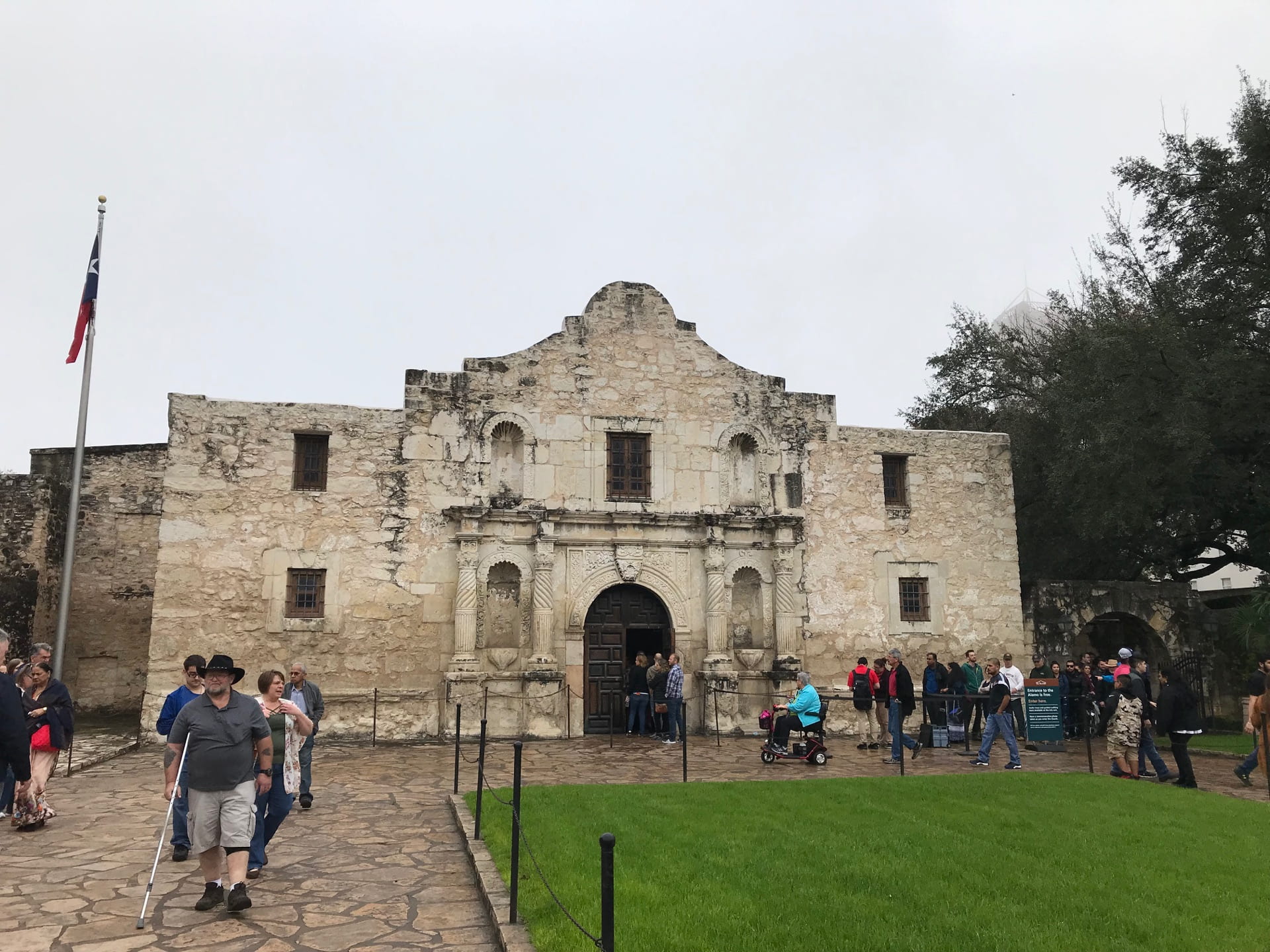

Alamo Mission (Photograph by Katherine Hite).

In 2016, I visited the Alamo, as part of my first real return to Texas in many years. I had mapped out a road trip with my brother Edmund Roberts. Though Edmund has long known of my interest in memorials, he had never traveled with me to the many sites of memory in places such as Chile and Argentina where I have done extensive fieldwork. This time was different. We flew into San Antonio, Edmund from California, me from New York. Later we headed east, through Austin and the state capitol grounds, the historic town of Goliad, and then onto Waco, where we visited the Texas Rangers Hall of Fame and Museum.

I had just begun to unlearn what I had learned as a young person growing up in Houston about the founding of Texas, the Texas Rangers and much more. Like many who grew up in Texas and now live elsewhere, I often feel torn about all the Texas pride I know I felt, and in fleeting moments, still do. After all, a celebratory story of Texas history, “The Story of Texas,” is firmly anchored in the K-12 school curriculum, required in both fourth and seventh grade. Bumper stickers with slogans like “Born and Built in Texas” abound. Messages of Texas’s greatness are pervasive, as are ideas about “Texas justice.” Stores market T-shirts boasting, “In Texas, we don’t call 911” under an image of a smoking gun. My stepfather, Glen Fields, from east Texas, has always worn a cowboy hat. When we went on family road trips, he carried a concealed gun (often in his boot), and he taught us how to shoot. As a teenager, I remember thinking that Texas state secession wouldn’t be a bad thing. Now, all these years later, as a student of the politics of memory and memorials from Latin America, reading Texas from Mexico and from the borderlands opened up for me the provincialism as well as the racist violence of the official story of Texas.

Alamo Cenotaph, also known as The Spirit of Sacrifice (Photograph by Katherine Hite).

For Texas, the Alamo represents the Texas Revolution, a heroic battle against Mexico’s centralizing grip, as well as the martyrs who paved the way to Texas independence in 1836 and the republic’s ultimate joining of the United States in 1845. For Mexico, the Alamo is a symbol of Anglo insurgency, and the leading Alamo occupiers were guilty of treason as well as slavery, which Mexico abolished in 1829. On the Mexico-Texas border today, a very real human crisis attests to the intense, centuries-old, interwoven histories of life, death, kinship, struggle and violent conflict over land tenure, capital and political jurisdiction.

Edmund and I spent a lot of our time on the road in our red Nissan Sentra discussing the state’s violent history, as well as our own whiteness. Though not unique to the state, white supremacy in Texas has also sown interracial division, both historically and now. With the growth of border studies, postcolonial studies, critical race theory and ethnic and gender studies, this is changing. Today multi-racial grassroots groups all over Texas—experts at coalitional organizing and activism— have been mobilizing to re-write textbooks, bring down monuments that shouldn’t be there and establish memorials that should be, including memorials to the many people of African and Latin American descent who were lynched, from the 1880s through the early 1940s.

In 2019, I returned to the Alamo, this time with a close friend from New York, Bryant “Drew” Andrews, an African-American man, who just by being with me in Texas for his first time, heightened my sensitivity about a dimension of the Alamo narrative I had not truly focused on before: the fact that enslaved African-American men were in the Battle of the Alamo itself. One of them died in the battle. As we stood inside the Alamo, we stared down at a plaque with the individual names of the dead, I could not claim that when I visited in 2016, I had really processed the one name on the plaque with no last name. All of the other men had first and last names and the U.S. state or the country they came from. But one name just read, “John _________, black freedman.” As Drew and I continued through the audio-guided tour, which did not discuss John, I listened to the narrative differently. The audio did mention the story of “Joe,” another “black freedman.” Joe had been enslaved by the Texas hero and commander at the Alamo William Travis and, by most accounts, Joe was the one male “serving” on the Texas side that the Mexican army allowed to survive and escape. Some historical accounts claim that another man who also managed to escape was “Sam,” who had been enslaved by Texas hero Jim Bowie. Sam is not in the Alamo audio, either. The claim that John, Joe or Sam were freedmen rang shamefully—they were still very much enslaved.

The 2019 audio guide rendered the tensions, ups and downs of the Texas rebels’ 13-day siege of the Alamo, in all its drama. The narrative anchored the site as sacred, beginning in the 17th century as a Spanish mission, “a place where indigenous people were converted to Catholicism, trained in Spanish culture and taught necessary skills to become productive members of society.” In point of fact, the Spanish missions of San Antonio were weak and under constant attack by Comanche and Lipan Apache indigenous peoples who fiercely opposed their encroachment into hunting and pastoral land. Throughout the 17th, 18th and early 19th centuries, San Antonio was a struggling Spanish territory, plagued by natural disasters (primarily drought and flooding) and by overwhelming, forceful indigenous opposition to Spanish colonization.

In the audio guide, visitors are introduced to some of the gory details of the battle itself. We heard the words of Susannah Dickinson, the wife of one of the rebels, who joined him inside the Alamo. Dickinson graphically described the Mexican soldiers as “the barbarous horde” that spear the rebels with bayonets, tossing the bodies “like a farmer does a bundle of fodder on his pitchfork.” The Mexican troops allegedly spared Dickinson’s life “as the only English-speaking survivor that day,” so she could report back to the Texas side. The fact that Joe must have spoken English and also survived dropped from the audio.

A deafening silence has long hung over the centrality of slavery to the Texas cause. It is true that Mexico’s northern states sought greater autonomy from Mexico City’s control over their terms of trade with an expanding United States, as well as with shipments overseas to satisfy major demands for cotton. Nevertheless, cotton and sugar production absolutely depended on slave labor, prohibited by Mexico. In addition, as historian Andrew Torget argues, even those cotton farmers who had yet to own enslaved men and women aspired to do so. That deep historical white desire to enslave Black men, women, and children helped set the stage for both the Texas Revolution and the U.S. Civil War.

The Alamo audio treated Native Americans as historical relics who were once bestowed the gift of missionary Christianity and civilization. It portrayed Mexican soldiers as bloodthirsty, their leader as an evil dictator. It denied the Texas revolutionary aim to preserve slavery and made the false claim that the enslaved men inside the Alamo were “freedmen.” In characteristic bravado, nonetheless, the audio tour ended by celebrating the freedom brought to us by “Texan, American, European, Tejano, Mexican and Freedmen.”

When Drew and I left the Alamo, we stood before the enormous “Spirit of Sacrifice,” the Alamo Cenotaph, outside the Alamo grounds. The cenotaph is sixty feet high, forty feet long, and twelve feet wide. At its base, eight panels figuratively depict the major leaders who died in the Alamo—William Travis, James Bowie, James Bonham and Davy Crockett—as well as other men poised to light the cannon and aim their rifles. On the north side of the cenotaph is a large, floating, female figure, flanked by the shields of Texas and the United States. Drew studied the stone portraits of the men in action, and then he asked, “Where’s Joe?”

A major battle is being waged today over how to tell the story of the Alamo. Some Alamo defenders are literally up in arms. An embattled official commission has been working for five years on a physical renovation, a re-haul of the site, and a re-telling of the story. Texas historians have long recognized the dominant denials of the facts behind the Texas Revolution. Yet a new book, Forget the Alamo, written by three white Texas journalists, has caused an explosion among Texas political leaders. The lieutenant governor denounced the book, orchestrating the abrupt cancellation of the authors’ scheduled appearance at the official state museum. Like Texas guns, there’s now no concealing the truths of Texas’s founding.

La Matanza

The struggle over a more recent moment in Texas history includes direct descendants of murdered Mexican-Americans sharing family histories and memories that have been passed down over time. It mirrors post-dictatorship human rights struggles over several generations I have witnessed in Chile, Argentina and elsewhere. This is the moment of the Mexican Revolution of the 1910s.

One museum that includes this period stands in Waco, Texas, the Texas Rangers Hall of Fame and Museum, a top tourist attraction. It’s got big gun displays, portrayals of the Rangers in popular culture, and accounts of individual Texas Ranger heroes. Nothing casts doubt on the Texas Rangers historical record. Edmund and I would point out to each other the tongue-in-cheek accounts of a Ranger exercising “Texas justice,” a shoot first, ask questions later approach to law and order. We watched a video in the museum that made a quick reference to a “not so bright” Rangers moment in the early 20th century at the time of the Mexican Revolution. During that period, Rangers killed masses of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans in south and west Texas.

- The Texas Rangers Hall of Fame and Museum

- Texas Rangers popular culture display (Photographs by Katherine Hite).

During the Mexican Revolution, a group of Mexican-Americans joined forces with a faction of Mexican revolutionaries. The Mexican-American revolutionaries drafted the Plan de San Diego, named for the small town of San Diego, Texas. It called for an alliance of Mexican-Americans, Native Americans, African-Americans and Japanese-Americans to violently retake the U.S. southwest under a reborn, revolutionary Mexico. Read today, the Plan de San Diego sounds shocking, even suicidal. Yet it is far less so in the context of the heated border disputes, Anglo land grabbing, brutality against ethnic Mexican workers, volatile local political alliances among Mexicans, ethnic Mexican Texans, Spanish-descended Texans, and Texas Anglos along the border, and the conflagration of the Mexican Revolution itself.

Between 1915 and 1916, more than a hundred ethnic Mexican revolutionaries raided U.S. ranches owned by known Anglo racists as well as by some Spanish-descended conservative Anglo allies. The revolutionaries rustled cattle and killed roughly 22 people. The porousness of the border allowed for a somewhat ready-made escape route to Mexico. The Texas Rangers’ reaction to the border incursions and guerrillas was absolutely brutal. Historians estimate that during the Mexican Revolution, Texas Rangers killed and lynched between 500 and 5,000 ethnic Mexicans.

Bazán-Longoria descendants of the Rio Grande Valley, in south Texas, whose loved ones were murdered by the Rangers in the early 20th century (Photograph featured by CNN, July 20, 2019).

In the home of the Plan, San Diego, Texas, also the Duval county seat, awareness or conversation about the Plan has been mostly under the surface. When I entered the Duval County Historical Museum office in 2018 and asked the director about the Plan de San Diego, she pointed me to a map on the wall, the city’s urban plan. Another staff person, however, overheard the conversation and took me into the back. She shared the portrait of the Plan’s revolutionary leaders with me and gave me the telephone number of another memorial activist who lost a relative during the Ranger repression. She also told me that when she and others proposed a public panel on the Plan at the local high school for its hundredth anniversary in 2015, the school board said no, voicing concerns about the Plan’s calls for violence against Anglos. The museum held the event in an upstairs room of the county courthouse. Nevertheless, the museum has announced a forthcoming historical marker of the Plan de San Diego, to be located on the museum’s grounds.

On June 4, 2020, triggered by Dallas reporter Doug J. Swanson’s new book, Cult of Glory: The Bold and Brutal History of the Texas Rangers, a well-known local statue of a Texas Ranger came down at the Dallas airport. As Texas border and labor studies scholar Sonia Hernández implied, it ultimately took a white man’s exposé to remove the Rangers monument. In 2018, scholar Monica Martínez published The Injustice Never Leaves You: Anti-Mexican Violence in Texas, in which she shares the accounts of descendants of those murdered by the Rangers. Together with other scholars and with descendants, Hernández and Martínez are co-founders of the Refusing to Forget initiative, a collaborative effort to memorialize and reckon with La Matanza, the massacre period. Refusing to Forget sponsored successful petitions to the Texas Historical Commission for new markers, as well as an impressive permanent roadside exhibit at a rest stop in Edinburg, in the Rio Grande Valley. Memories of the descendants are becoming more visible.

Behind the bravado of dominant Texas narratives, there is a haunting. Conservatives in the Texas legislature are ferociously fighting to put the brake on. Social movements, supported by critical historians, memory scholars, educators, political and community activists, some sympathetic politicians and descendants of the victims of Texas state-sponsored terror, are forcing a reckoning. Those who were murdered by the Texas Rangers haunt small Texas border towns, as do African-Americans who were lynched in other Texas towns and cities during the same period, where activists and some descendants are also pressing for their recognition. Memorial activism evokes for me the term presente, a cry to recognize the presence of those who are no longer with us. Change of the dominant story of Texas is inevitable— resisted and hard— but there’s no turning back.

Spring/Summer 2021, Volume XX, Number 3

Katherine Hite is Professor of Political Science on the Frederick Ferris Thompson Chair at Vassar College. She is the author of Politics and the Art of Commemoration: Memorials to Struggle in Latin America and Spain. Katie is active in her Poughkeepsie, New York, community, including as co-chair of Celebrating the African Spirit.

Related Articles

The Eye that Cries: Peru’s Unreconciled Memories

English + Español

In Lima, Peru, in the midst of Campo de Marte, a public park named after the god of war, a Zen space for reflection is guarded by a cast iron fence. El Ojo que Llora (“The Eye that Cries”…

Editor’s Letter: Monuments and Counter-Monuments

Cuba may be the only country on the planet that sports statues of John Lennon and Vladimir Lenin. Uruguay may be the first in planning a full-fledged monument to the victims of the Covid-19 pandemic.

My cry into the world

English + Español

It was September 20, 2019. “One hundred, two hundred, three hundred, four hundred….” That was how we felt and that was how we counted in the face of the irremediable absences provoked…