A Nation at War with Itself

The Role of U.S. Advisers

In January 1981 the U.S. Embassy in El Salvador headed by Robert White sent an urgent cable to the Department of State in Washington. The memo, labeled SECRET, alleged that the death squads responsible for hundreds of political murders in the war-torn Central American nation were being funded and directed by a cabal of six Salvadoran businessmen who lived in Miami. The cable, based on information from a “highly respected Salvadoran lawyer” who was about to flee for his life, blamed the six for the assassination earlier that month of a Salvadoran land reform advocate and two U.S. labor officials who were meeting at San Salvador’s Sheraton hotel. “The time has come,” the memo said, “to investigate these charges and, if proven, to arrest the perpetrators and prosecute them to the full extent of U.S. law.”

It is not clear whether any investigation of the six was undertaken. What did happen is that Ambassador White, who railed against the right-wing violence, was fired around that time by the incoming administration of President Ronald Reagan, and in the next few years military and economic aid to the Salvadoran regime dramatically increased. With Nicaragua and Cuba supplying arms to the Salvadoran rebels, and a separate leftist insurgency on the boil in Guatemala, the Reaganites had an apocalyptic vision of all of Central America gone red. “The attitude of the Reagan Administration in its first two years was that we had no enemies on the right,” says Donald Hamilton, chief public information officer at the U.S. Embassy in El Salvador from 1982 to 1986.

Critics of U.S. policy in Central America—from Peter, Paul & Mary to Joan Didion—asserted that the United States, in its anti-communist fervor, aided and abetted Salvador’s right-wing killers, or at best did too little to stop the slaughter, in which at least 30,000 civilians were killed. U.S. officials who were on the ground in El Salvador in the 1980s remember it differently, saying they did their best—short of cutting off aid—to curb the wanton violence on the government side and professionalize the Salvadoran military. The 10-year conflict ended with a negotiated settlement in 1992.

One eyewitness to the violence was Robert Nickelsberg, whose photos of U.S. Special Forces advisers illustrate this story. He covered Central America’s wars from 1981 to 1984 for Time magazine from his base in San Salvador.

One of Nickelsberg’s tasks was to venture out on many mornings to take photos of the latest batch of dead bodies dumped by the side of the road in the capital. This put him in what he calls a “macabre competition” with local funeral directors, who would scour city streets for new business. The victims “were killed with a bullet to the back of the head, or by having their throats slit,” Nickelsberg says. “They would be bruised, with their hands tied behind their back.” In the countryside, he says, “the white hand of death” would mark the next victim. “A palm print in white paint would appear on someone’s door. And they would die.”

However sickening the killings were, “you had to document this,” Nickelsberg says. “I was personally very affected by it.”

El Salvador had been a nation at war with itself for a hundred years when the United States intervened in 1979. Its economy, and most of its wealth, had long been controlled by a small coterie of ranchers and businessmen—the so-called 14 families—with close affiliations to the national police and military. Through much of the 20th century this elite lived a paranoid existence in one of the poorest and most overcrowded countries in the hemisphere. Anyone who proposed social action to reduce poverty—particularly land reform—was labeled a communist. And starting in the 1970s, those activists began to die in large numbers.

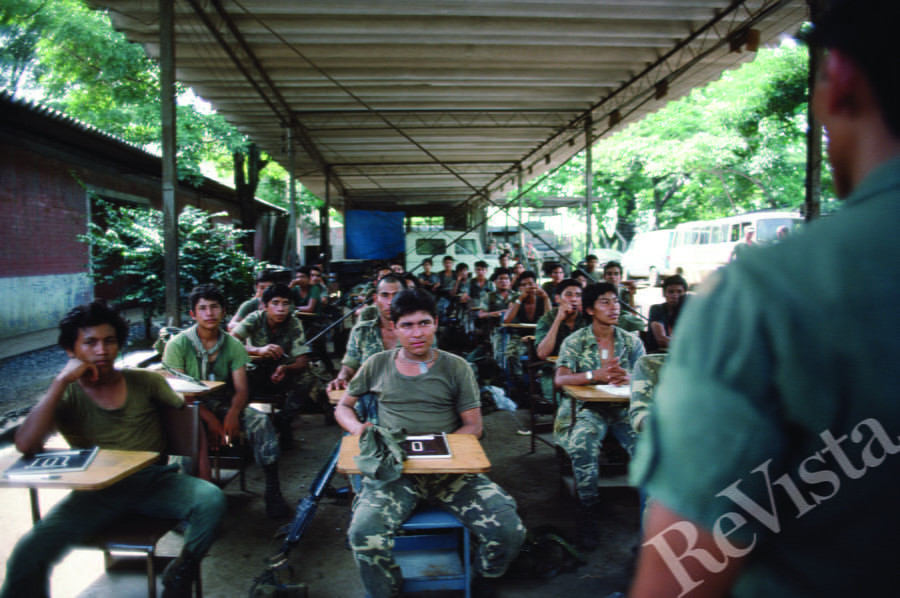

Recoilless rifle training at San Miguel, El Salvador, 1984. The advisers’ goal was to professionalize a sometimes brutal Salvadoran military.

The United States took little interest in El Salvador until the Sandinista victory over Nicaragua’s Anastasio Somoza in July 1979—an event that inspired Salvador’s own guerrilla coalition, the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), and provided it with a source of arms from their neighbor to the north. The FMLN would eventually field 12,000 fighters and control a wide swath of northern and eastern El Salvador. In late 1979, President Jimmy Carter, as eager as his successor, Reagan, to prevent another leftist victory in Central America, stepped up military aid substantially. The United States would spend $6 billion on aid to El Salvador between 1980 and 1992, according to a 1996 study of U.S. military involvement by then-Army Major Paul P. Cale. Looking back, Hamilton finds the United States’ huge investment in the Salvadoran conflict extraordinary. Until 1979, “we had shown ourselves very capable of ignoring El Salvador’s existence,” says Hamilton, 68, who now declassifies documents for the State Department. “We’re talking about five million people in a country the size of Massachusetts.”

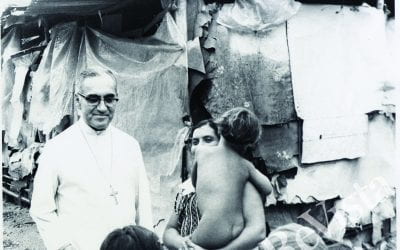

The outbreak of full-scale civil war is usually dated to the March 1980 assassination of Archbishop Óscar Romero, a fearless critic of government repression, who in one of his last sermons called for an end to U.S. military aid. It was the time of “liberation theology,” and 11 priests active on behalf of the poor were killed in three years, according to a history of the conflict by William Blum. (It may be apocryphal, but it is said that the slogan of one death squad was, “Be a Patriot, Kill a Priest.”)

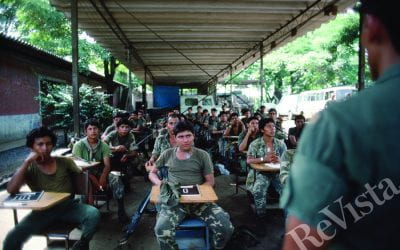

Counterinsurgency training. A priority was converting pro-rebel peasants through a “hearts and minds” campaign.

It would take the kidnapping and killing of three American nuns and a lay church worker in December 1980 to force a suspension of U.S. military aid. (Four members of the National Guard were later imprisoned for the crime—but not before what the 1993 United Nations Truth Commission report labeled a cover-up by authorities.) Soon after the churchwomen’s murder, the FMLN launched an offensive so fierce Washington feared a rebel victory, and the Carter administration resumed aid.

The worst of the political violence took place between 1980 and 1983, according to journalists and diplomats who worked in El Salvador at the time. “The deaths and the bodies never stopped,” says Nickelsberg, recalling that his housekeeper, who walked to work, often alerted him that the killers had been at work the night before. The United States was both ally and enemy, says Clifford Krauss, who covered the El Salvador conflict for The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times. “I was in the U.S. Embassy when it was attacked by the death squads in 1980,” he says. “It was a complex relationship that wasn’t always friendly.”

Far from ignoring the carnage, Hamilton says that Deane Hinton, U.S. Ambassador from 1981 to 1983, lobbied hard, privately and publicly, for the government to get the military and the three branches of the national police—the National Guard, the National Police and the Treasury Police—under control. In April 1982, a tough Hinton speech to the American Chamber of Commerce made front page news in the United States. “The gorillas of the right are as dangerous as the guerrillas of the left,” he told the businessmen.

“The official American community [in El Salvador] was largely outraged by what was happening,” Hamilton comments. “One of the hardest things for us was explaining away the stupid things they were saying in Washington.” There, officials including Reagan aide Gen. Alexander Haig, U.N. Ambassador Jeane Kirkpatrick and North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms vigorously defended U.S. involvement in the war and labeled allegations of atrocities as FMLN propaganda. Helms befriended former military officer Roberto D’Aubuisson, founder of the right-wing ARENA party, who is now acknowledged as the author of much of the death squad violence, including the murder of Archbishop Romero. In that 1981 cable to the State Department, he was identified as the agent in El Salvador of the Miami Six. He died in 1992.

Salvadoran soldiers lectured on human rights in August 1984. The slaying of six Jesuit priests in 1989 suggested the training “didn’t amount to anything,” say reporter Preston.

While Hinton strove to convince officials in San Salvador and Washington that murdering the opposition was not a viable strategy, Col. John Waghelstein was trying to persuade the Salvadoran military of the same thing. A counterinsurgency expert who now teaches at the U.S. Naval War College, from 1981 to 1983 he was in charge of the small squad of military advisers who taught Salvadoran soldiers how to use American weapons, instructed army officers in tactics and strategy, created a signal corps and, most important in Waghelstein’s view, gave lessons in “low-intensity conflict”—that is, pacifying a rebellious populace with kindness rather than bullets. The most famous convert to this “hearts and minds” strategy, Waghelstein says, was Lt. Col. Domingo Monterrosa, head of the U.S.-trained Atlacatl Battalion. That was the army unit that several investigations confirmed was responsible for the December 1981 massacre at El Mozote, in which troops systematically killed as many as 1,000 people, many of them women and children, in that village and surrounding communities. By the time Monterrosa was promoted to head all military operations in eastern El Salvador in 1983, he had undergone a transformation. After his troops took a village from the rebels they would set up camp and build roads and schools, distribute food and provide medical care. The charismatic commander would make speeches telling the farmers they could trust the army to provide for their needs better than the rebels. As Mark Danner tells it in his book, The Massacre at El Mozote, the campaign was so effective that the rebels set out to kill Monterrosa—which they did in 1984 by planting a bomb aboard his helicopter.

Retired U.S. Ambassador to El Salvador, Thomas R. Pickering, 84 years, sits in his Washington, DC office of Hills & Company where he is a Vice Chair overseeing international trade, politics and diplomacy November 12, 2016. Ambassador Pickering served in El Salvador from 1983-1985. Pickering agreed to take the job after Secretary of State George Schultz assured him that the United States would no longer stand by while hundreds of civilians, including officials of the moderate Christian Democratic Party, were gunned down. (Photo by Robert Nickelsberg/Getty Images)

The United States supplied the Salvadoran military with hundreds of millions of dollars worth of weapons and ammunition—including dozens of transport helicopters and fighter planes. The challenge was to train the troops in the weapons’ use within the strict limits agreed to by the Reagan administration under the watchful eye of congressional critics. The number of military advisers could not exceed 55, and they were forbidden from engaging in any combat, or even accompanying Salvadoran troops into the field—though according to reporters who covered the conflict the last restriction was sometimes ignored. “The limits came because of concern in Congress about mission creep like Vietnam—that with large numbers of U.S. military in place it would result in some kind of debacle,” says Thomas Pickering, U.S. ambassador to El Salvador from 1983 to 1985. The embassy kept a running count of the advisers “almost on an hour by hour basis,” Pickering says. “Often if we needed some particular help we had to move people out of the country before moving people in.” As Waghelstein says: “The beauty of the 55-man limit was it that it was hard to argue that this is like Vietnam.” It also made clear to the Salvadoran military that it was their war to win or lose.

Scott Wallace, a freelance reporter who worked for CBS News and was based in El Salvador from 1983 to 1985, spent much of his time in the province of San Vicente, where many U.S. military advisers were introducing counterinsurgency methods to the Salvadorans. One of the advisers’ main jobs was training members of a new civil defense force, “to teach the locals how to defend their towns from attack, train them in handling weapons and to respect the rights of their fellow citizens,” Wallace says. “These forces ended up being cannon fodder in guerrilla attacks throughout the territory. Guerrillas would overrun these thinly defended towns, execute the civil defense people and the army would get there too late.”

The advisers included Army Special Forces, Navy SEALS and Air Force flight trainers. Especially in the early years, the U.S. government skirted the 55-man unit by training hundreds of Salvadoran soldiers and officers in Honduras and at U.S. bases in Panama and the United States—often at great cost. One crucial need the advisers met was the training of a field medical service and the provision of MEDEVAC helicopters. Before those units were in place, “it was like the [U.S.] Civil War,” says Pickering. “If you were wounded your chances of dying were pretty high.”

By all accounts, the tide of U.S. policy turned in late 1983 with the appointment of Pickering as ambassador. Pickering, now 84, says he only agreed to take the job after Secretary of State George Shultz assured him that the United States would no longer stand by while hundreds of civilians, including officials of the moderate Christian Democratic Party, were gunned down. Pickering’s arrival in September 1983 coincided with a three-month guerrilla offensive that, he says, prompted a “significant upturn” in political murders. In December Pickering asked Vice President George H.W. Bush to stop in El Salvador on his way back from a trip to Argentina. Bush delivered a blistering public speech in which he denounced the “cowardly death squad terrorists.” Then, according to Pickering, he told a private meeting of colonels and generals that if the killing continued there was nothing the Reagan administration could do to stop Congress from cutting off military aid. “Up until then I think they thought Reagan would be sympathetic with anything they did,” Pickering says. The killings did diminish, in part because the Salvadoran government agreed to ship a half dozen officers suspected of death-squad activity to foreign postings.

The next step was the establishment of a legitimate government—accomplished in 1984 with the election of Christian Democrat José Napoleón Duarte as president. (His main opponent was D’Aubuisson.) To great fanfare, Duarte launched negotiations with the guerrillas. But there would be a great deal of ruthless killing on both sides before the war finally sputtered to an end. One gruesome catalyst was the 1989 murder of six Jesuit priests, their housekeeper and her 15-year-old daughter—a last spurt of violence, it has been shown, from the Atlacatl Battalion. “After all that reform and training, lectures and diplomatic threats, it really didn’t amount to anything,” says Julia Preston, a New York Times reporter who covered the war for The Boston Globe and The Washington Post. “They ended up committing this crime that shocked the world’s conscience.”

Says Pickering: “The mindlessness of the killing of the priests had to be an example of how frantically concerned the hard right was” at the prospect of a negotiated settlement. As U.S. ambassador to the U.N. from 1989 to 1992, he played a “subterranean” role in those peace talks, which were led by Colombia, Mexico, Spain and Venezuela. “I spent a lot of time with the Salvador government legation,” he says. “Others in my mission at the U.N. were reached out to by guerrilla organizations. So we had the opportunity to do our bit to support the negotiating effort. “

What really ended the war, according to The New York Times’ Krauss, was an event thousands of miles away—the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union. “When I look back from 3,000 feet I see it all as a battle in the Cold War,” he says. “When the Berlin Wall went down it ended all these proxy wars.” He is convinced that without U.S. help the country would have fallen to the FMLN, an outcome no one wanted. The U.S. accomplishment was to help the Salvadorans “draw out the war until the end of the Cold War.”

A U.S. Army officer inspects a Salvadoran’s M16. The number of advisers was never permitted to rise above 55

In the end, of course, the FMLN did win—taking control through the ballot box in 2009. “But that’s the way it should be,” says Waghelstein. A former FMLN comandante, Salvador Sánchez Cerén, is now president.

Former embassy staffer Don Hamilton, for his part, looks back on the U.S. role in the conflict with regret and a subversive thought: “It’s not that hard to make the case that we were on the wrong side in that war. I don’t believe we were, but I don’t think we covered ourselves in glory either.”

Spring 2016, Volume XV, Number 3

Michael S. Serrill is a freelance writer based in New York and a former foreign editor for Bloomberg News and Business Week. He edited stories on the Central American conflicts for Time magazine in the 1980s and 1990s.

Robert Nickelsberg, a Time magazine contract photographer for 25 years, was based in El Salvador from 1981 to 1984. He covered the civil wars, unrelenting violence and the effects of U.S. foreign policy in Central America with particular focus on El Salvador and Guatemala before relocating to Asia. This is the first time his images of the U.S. military advisers have been published.

Related Articles

The Boy in the Photo

The mangy dogs strolled everywhere along the railroad track. I remembered dogs just like them from the long-ago day in La Chacra in 1979 with Archbishop Óscar Romero, just months before he was killed…

Beyond Polarization in 21st-century El Salvador

My father was a civil engineer who worked for the government during the civil war years. He specialized in roads and had to spend several days a month traveling to remote places in El Salvador. I was 10 in 1986, and I remember my mom asking my dad…

El Salvador: Editor’s Letter

I had forgotten how beautiful El Salvador is. The fragrance of ripening rose apples mixed with the tropical breeze. A mockingbird sang off in the distance. Flowers were everywhere: roses, orchids, sunflowers, bougainvillea and the creamy white izote flower…