A New Museum for Independence

Renovating Memories

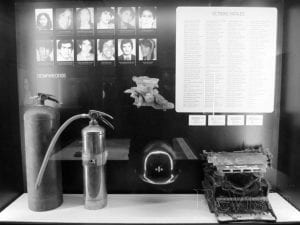

The new Museum for Independence honors victims of the conflict in its hot spot project. Photo courtesy of Museo De La Independencia-Casa Del Florero

This is a very short story of how a small museum in Colombia underwent a profound process of change and renovation, tackling sensitive and controversial issues of memory in recent Colombian history.

The independence of Colombia is celebrated every July 20, because on that day in 1810, a group of creoles (children of Spaniards born in America) started a fight with a Spaniard who refused to lend them a flower vase. That initial fight sparked a riot that eventually ended in a declaration of independence.

In 1960, 150 years later, the house where the fight started was restored and made into a museum. This house-museum, a memorial for the veneration of the country’s heroes, not only was anachronistic but really boring for visitors at the beginning of the 21st century. A change was necessary.

However, real change (not just the cosmetic change in display cases and graphic design that most museums dream of) is hard to achieve. It takes a lot of time and resources, but also demands a change of attitude, both in the way the museum views the visitors, and most difficult, the way visitors see the museum.

In 2002, we (one of us the director and another a close advisor) started to think about how to make that change. Several questions came to mind: How to involve visitors actively, (not just as survey numbers)? How to challenge historical preconceptions? How to defy the sanctity of the museum? As it is the birthplace of the nation, change might feel like sacrilege. The museum had also evolved as a place of memory; it had been the staging ground for the Army during the horrific Palace of Justice siege in 1985 that left half of the Supreme Court justices dead. We wanted to honor old memories, but we were not sure about incorporating the newer ones.

The first initiatives were of course based on the old exhibition design. We started to ask visitors about the very essence of the museum, the concept of independence (understood as a concept and not as a historical fact). Visitors were invited to write their own independence declaration, to sit on a sofa from the collection and “feel” independent (it was a play on words, as in Spanish the word “seat” [sentarse] is very similar to the word “feel” [sentirse]), to “break” the historical flower vase (at least a jigsaw puzzle of it) and then reconstruct it.

A survey even consulted the public about changing the name of the museum (it used to be called the “Museum of July 20, 1810”). People agreed with us that it should be called “The Museum of Independence.” Based on the survey, we developed a new plan following a participative, interdisciplinary and inclusive model, trying to bring in as many points of view as possible (architects, museum professionals, anthropologists, historians, politicians, artists, journalists, conservators and many others). The result was then presented, evaluated and approved by experts in Colombia and abroad. We finally had a plan for change.

Magnetoscopio, an internationally renowned exhibition design firm, was hired to materialize the concepts of the plan, and finally ideas started to take a physical shape. Colombians would have an innovative space to think about new ways of understanding the concepts of autonomy, liberty and independence.

However, one question still had no answer…

That was what to do about the relationship of the museum to the Palace of Justice siege 28 years ago. To make a political statement, a group of the M-19 guerrilla took over, in 1985, the building housing the Supreme Court directly in front of the museum. The Army— using the museum as its operation center — entered the Palace by force, killing several employees. After a couple of hours, the Army takeover became a slaughter. To make a long story short, the result was: around 117 people killed, 12 people still disappeared and the building burnt down to the ground.

After the massacre, the museum went back to its normal life, avoiding the issue as a subject of its exhibitions, as if nothing had happened. We knew we had to change this in our renovation, but there were several considerations.

The case is not closed yet and investigations are still ongoing.

The museum is a National Museum, operating under the Ministry of Culture, and hence everything the museum offers is basically an official message; in a way, it is the government speaking. Most of the accused (for using unnecessary force) are members of the Colombian Army, and because of that, there is a feeling that the government does not agree with the accusations made against them.The guerrilla group signed a peace treaty in 1990 and most of its militants were pardoned. However, at the time of the museum reopening (2010), they faced open opposition from then-President Álvaro Uribe, who accused them of being “terrorists.”

In 2009, at the Reykjavik annual ICOM/CECA (International Council of Museums/Committee for Education and Cultural Action) Conference, a Swedish museum gave a presentation that related its experience with a project called “Hot Spot: Awareness-Making on Contemporary Issues in Museums.” That concept was exactly what we were looking for. We contacted the people responsible for the Hot Spot project in order to get their permission to duplicate their initiative. Their reply went even further:

“I [the project director] believe that the museum can play an enormously important role to mediate burning issues and invite the surrounding society and open up for debates. To connect a hot spot exhibition to the more ‘traditional’ exhibition is a very good idea. I recommend you invite people, collect their stories, invite experts that have unique experiences about the issues. Try to take some risks, use strong photos, films, and objects.”

Now we had a strategy that we could follow. We thought of some ideas for the display, and we brought in some objects from the Palace of Justice; a video showing news from the time; an introductory text with four kinds of information (the facts or “cold figures,” the motivation of the guerrillas, the motivation of the army and a plea for a truce made by a magistrate caught in the crossfire); a list of all the people killed; images of the people who are still “disappeared” and we provided a mechanism for visitors to record and display their feelings and opinions about the issues.

Although it was a very sensitive topic, most of the elements listed above were easy to find. However, the problem was how to pose the question to the public. We did not want people to just read the information given and “take a side.” We wanted to, somehow, make visitors realize that there were several motivations for each side to do what they did. We aspired to activate critical thinking, rather than polarize opinion. After long discussions, we ended up formulating five questions that we hope can trigger critical opinions: To forget? To remember? To forgive? To condemn? To repair?

Then the real challenge began. How would people react to the exhibition? Would they be annoyed? Would someone feel attacked or just indignant? Would such a person break something in the museum, or damage the exhibition? Would people complain to the press or directly to the Ministry of Culture? And most importantly: Would people even care?

Since the museum reopened, we had had more than 500,000 visitors. Only about a hundred have complained they do not like the change. They miss the old museum. Some don’t like the fact that there is not guide (they seem to reject independence!). However, there had been just five complaints about the Hot Spot. Visitors actively participate by answering the questions (which are then exhibited, along with pieces from newspapers that come up virtually every day with judiciary decisions about the incident). Indeed, many even say that this is their favorite part of the museum.

Maybe the most interesting complaints come from people that were involved in the 1985 events. We have received a couple of “rights to petition” from the lawyers handling the cases of the people disappeared in the Palace of Justice and more recently, one from the lawyer of the family of one of the coronels that has been sentenced to jail for misuse of power. In both cases we have had to seek legal counsel and reply to their claims with museological arguments.

When you get reactions like these (when both parts affected feel that the other part should not be displayed, with arguments like “those who forget their history are bound to repeat it”), the first reaction is often an angry one. There are of course many arguments to defend the presentation of all the actors involved. But then, most of the time, a simple explanation of why we did things the way we did suffices to diffuse angry feelings. And at the end of the day, it is great to see that people actually read what is displayed, and get touched by it. The museum made people active. We would rather have a legal complaint every week than have no reactions at all.

Finally, we think that participation (and most importantly, involvement) of our public is a key element in everything the museum does. Given that participation is one of the principles of the new 1991 Colombian Constitution, we deliberately want to be consequent and take action as a result. It was not something we did just for the renovation. We keep asking our visitors about their feelings for future exhibitions: What would you want to know?, What would you like to see? What do you think? How does something make you feel?

It is not just a way of giving them the false illusion of participation; it is the way the museum wants to be, a place for dialogue. That is why our motto is “a place where history is built by your own history.”

It may sound like a utopia, but it is certainly one we would like to involve our visitors in, at least two ways: poetically and politically. Poetry implies the way in which we share knowledge and experience, and politics is seen as the compromise we have to accomplish as active citizens.

Daniel Castro is an artist, musician and educator with an MA in History from the National University of Colombia. He is director of two historical museums of the Ministry of Culture of Colombia (the Museo de la Independencia-Casa del Florero and the Casa Museo Quinta de Bolívar).

Camilo Sánchez is an Industrial Designer and MA in Museology from the University of East Anglia. He is currently the museological advisor of the Museo de la Independencia-Casa del Florero and the Casa Museo Quinta de Bolívar.

Related Articles

A Search for Justice

In 2004, when I left Harvard and last saw you, I thought I would never learn the truth of what exactly happened to Carlos Horacio in the horrendous holocaust of the Palace of Justice in Bogotá. Yet fate was holding a tremendous surprise for my daughters and me, filled with…

Memory: Editor’s Letter

Editor's Letter Memory Irma Flaquer’s image as a 22-year-old Guatemalan reporter stares from the pages of a 1960 Time magazine, her eyes blackened by a government mob that didn’t like her feisty stance. She never gave up, fighting with her pen against the long...

A Search for Justice in El Salvador: One Legacy of Ignacio Martín-Baró

In the small rural town of Arcatao, Chalatenango, Rosa Rivera clung to the hope that one day she would find the remains of her disappeared mother and father and lay them to rest in peace. Others sought to exhume mass graves hoping to recover bodies of nearly 1,000 relatives massacred in the Río Sumpul. …