A Review of Llamas beyond the Andes: Untold Histories of Camelids in the Modern World

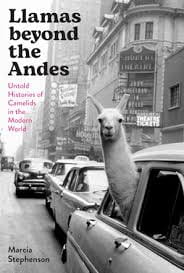

Llamas beyond the Andes: Untold Histories of Camelids in the Modern World by Marcia Stephenson (University of Texas Press, 2023, 380 pages)

Having mined archives in the Americas, Australia and Europe, Stephenson focuses her study on llamas and alpacas as “contact zones,” or nexuses centering human intercultural encounters. This includes their role as commodities to be extracted from their Andean home to benefit European medicinal and manufacturing demands. After 1492, the bodies of Andean camelids became yet another means to exhibit the construction of human hierarchical and imperial standing, she tells us.

Hierarchies and the methods of dominance display shift and evolve over time, and Stephenson is quite aware of this. The book starts its presentation of Andean camelids as intercultural “contact zones” with an engraving from the 17th-century account of the Brawern-Herckemann Dutch military expedition to Chile. In the engraving, a Dutch soldier points at an animal identified as a “camel-sheep,” while other humans in the image include an Indigenous Mapuche woman and man standing “proprietarily” behind the animal (pp. 9-10). The description that Stephenson gives sets the tone of her book. Andean camelids remain property, subject to being studied, dissected, traded, stolen and slaughtered.

This story begins with Nicolás Monardes, indebted physician and entrepreneur of 16th-century Seville, promoting bezoar stones found in the entrails of camelids as a means “‘to counteract venom and fainting spells’ (p. 31).” Since the Middle Ages, physicians in the Islamic World and Christendom had sought to counteract poisons with stones taken from Asian deer and goats. Monardes used the “occult” properties of the llama’s (and other Andean camelids’) bezoars to sell copies of his three-volume Historia medicinal. Not so much a self-conscious fraud as an individual driven simultaneously to pay his debts and promote the grandeur of his empire, Monardes foreshadowed later-day exploiters of llamas and their kin, Stephenson relates.

Some two centuries later, another empire launched an entrepreneurial effort to display power and preeminence through consumption. With both an interest in natural history and economics, the Emperor Napoleon’s wife, Empress Joséphine de Beauharnais maintained a menagerie at her Malmaison estate that included a female orangutan, kangaroos and a llama pair who eventually had at least two offspring. She worked with Spanish allies to acquire alpacas and vicuñas, while French fashion at the time promoted vicuña shawls for ladies (pp. 104-118). It is in her failed efforts to create a manufacturing industry based on camelid fiber that the difficulties in relocating large groups of these animals first became apparent.

In the mid-19th century, the Paris Acclimatization Society continued to try to transport animals to France to be used as resources, with luxury fibers from American camelid hair one of the items of interest. With the assistance of a local Bolivian priest, the Frenchman Eugène Roehn was somehow able to acquire a flock of alpacas and llamas from reluctant Indigenous Americans. And it was a disaster for the animals: “By the time Roehn and his group reached the French port of Bordeaux, the original flock from Bolivia—108 alpacas, 20 llamas, and 2 vicuñas—had been reduced to 35 alpacas, 9 llamas, and 1 vicuña.” (p. 140) Gastrointestinal problems, mange and the stress of tropical heat and tumultuous waves on long voyages took their toll. However, there is evidence that humane and thoughtful care on board ships made a difference. Two French ships’ captains reduced casualties transporting Ecuadorian llamas by having sailors place cushions on the inside of stables, shearing animals to deal with heat and providing fresh water daily. Of 48 animals who boarded in Ecuador, 26 arrived in France (pp. 148-153).

As transport practices improved, those camelids who were not sacrificed during oceanic crossings often merely faded from the historical record as interest in their use value evaporated. The oft-told Victorian adventure story of Charles Ledger (1818-1905), who lost £7000 in transporting alpacas and llamas to New South Wales Australia, is once again meticulously recalled by Stephenson. It is an excellent case study to substantiate her argument that llamas and their relatives served as cultural contact zones. To Ledger’s credit, he sometimes praised particular Indigenous shepherds for their skills and what they had taught him about Andean camelids. However, his plan to use a large, diverse herd to hybridize alpacas and llamas in Australia ultimately collapsed when the New South Wales government sold the animals off in small lots. The llamas and alpacas faded from the story, having served as a backdrop to human cultural and economic history.

This “fading-to-black” is even true of celebrities like Llinda Llee Llama. Once, she was present with ten South American ambassadors at the Dallas department store Neiman Marcus’ Latin American Fortnight in October 1959, appearing in ads and photo ops for a gathering intended to enhance Pan-American relations through consumerism. By the mid-20th century, with vicuña coats being sold as chic items of clothing in the United States, and with Latin America being seen as a source of purchasable exoticism in U.S. stores, “Llinda Llee’s starring role can be read as the culmination of the advertising strategies” used by a North American consumerist empire (p. 283). Marcia Stephenson is at her best when she writes that a present-day statue of Llinda Llee Llama at the Statler Hotel in downtown Dallas “represents a specific animal and her history”—an animal whose account of her life ends abruptly after her participation in the Neiman Marcus South American Fortnight.” Llinda Llee Llama simply “vanished from the historical record after October 1959.” (pp. 288-289)

The somewhat new field of historical animal studies spills much ink on animals used as resources and labor, but it also seeks moments when they rebelled by running away or refusing to work, like the stereotypical “stubborn mule.” When Andean camelids refused to eat aboard ship and were force-fed was this a choice not to acclimatize to their captivity (p. 215)? When, after contentious negotiations with male Bolivian village elders at Vilca Pujio, 35 to 40 Indigenous women pursued the alpacas Ledger had purchased for more than 300 miles, “demanding that the alpacas be returned to them,” while “‘howling, crying, and screaming,’” I was left wondering whether these women were eventually placated because Ledger gave them provisions and coca or because he may have agreed to be kind to the alpacas as they “begged” him to be (p. 176)? A full-fledged account using the current methodologies of historical animal studies would spend some time unpacking this incident to understand all the dimensions of these Andean women’s interactions with the alpacas. Sociologist Edmundo Morales, in his book The Guinea Pig: Healing, Food, and Ritual in the Andes (University of Arizona Press, 1995, p. 11) states that late 20th-century Andeans treated “big work animals like pets and often name them after plants, flowers, natural forces, and mountains,” while guinea pigs to be eaten were seldom named. In my own research for The Animals of Spain: An Introduction to Imperial Perceptions and Human Interaction with Other Animals, 1492-1826 (Brill, 2011), I read in Viaje a la América meridional by the scholarly naval officer Antonio de Ulloa (1716-1795) that Indigenous Americans in Quito demonstrated great affection for their dogs and that Indigenous women only sold their chickens with great sorrow (pp. 213-214). Was that sorrow manipulation in a transactional marketplace activity? Perhaps, but these multiple examples through the centuries of naming and affection shown nonhuman animals demonstrate what appears to be human care and concern. Could those 35 to 40 women who followed Ledger for more than 300 miles have been certain he would give them supplies and coca? Were they only interested in material gain, or were they trying to uphold traditional nonmonetary relations with the alpacas that the men were willing to trade away?

I also think that Stephenson might have used our contemporary understanding of camelid evolution, ecology and ethology to better explore behavioral tracks left behind in human documents. Helen Cowie, in her brief but extremely informative Llama (Reaktion Books, 2017) takes this biocultural approach and might be read together with Stephenson’s book to enhance an understanding of why the animals we exploit—and sometimes cherish—thrive, turn on us or die. By searching the documentation for evidence of the bonds that camelids and humans may have developed, and by trying to understand a llama’s needs through ethological observations of their behaviors, we can write something about their experiences as inhabitants of Earth. For a brief moment, Llinda Llee Llama experienced the strangeness of an automobile ride in New York City. She had a unique history, which Marcia Stephenson records. She is now remembered, after being used and discarded as a cultural contact zone.

Abel Alves teaches history at Ball State University and is author of two books and several articles. “The Animal Question: The Anthropocene’s Hidden Foundational Debate,” on modern empires and nonhuman animals, is available at the História, Ciências, Saúde—Manguinhos website.

Related Articles

A Review of Negative Originals. Race and Early Photography in Colombia

Negative Originals. Race and Early Photography in Colombia is Juanita Solano Roa’s first book as sole author. An assistant professor at Bogotá’s Universidad de los Andes, she has been a leading figure in the institution’s recently founded Art History department. In 2022, she co-edited with her colleagues Olga Isabel Acosta and Natalia Lozada the innovative Historias del arte en Colombia, an ambitious and long-overdue reassessment of the country’s heterogeneous art “histories,” in the plural.

A Review of Megaprojects in Central America: Local Narratives About Development and the Good Life

What does “development” really mean when the promise of progress comes with displacement, conflict and loss of control over one’s own territory? Who defines what a better life is, and from what perspective are these definitions constructed? In Megaprojects in Central America: Local Narratives About Development and the Good Life, Katarzyna Dembicz and Ewelina Biczyńska offer a profound and necessary reflection on these questions, placing local communities that live with—and resist—the effects of megaprojects in Central America at the center of their analysis.

A Review of Authoritarian Consolidation in Times of Crisis: Venezuela under Nicolás Maduro

What happened to the exemplary democracy that characterized Venezuelan democracy from the late 1950s until the turn of the century? Once, Venezuela stood as a model of two-party competition in Latin America, devoted to civil rights and the rule of law. Even Hugo Chávez, Venezuela’s charismatic leader who arguably buried the country’s liberal democracy, sought not to destroy democracy, but to create a new “participatory” democracy, purportedly with even more citizen involvement. Yet, Nicolás Maduro, who assumed the presidency after Chávez’ death in 2013, leads a blatantly authoritarian regime, desperate to retain power.