A Review of The People’s Poet: Life and Myth of Ismael Rivera, an Afro Caribbean Icon

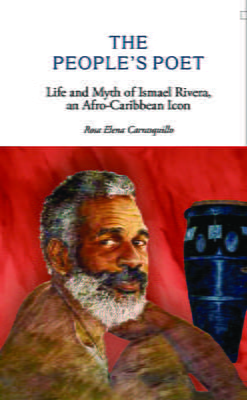

The People’s Poet: Life and Myth of Ismael Rivera, an Afro Caribbean Icon

By Pedro Reina-Perez

The People’s Poet: Life and Myth of Ismael Rivera, an Afro Caribbean Icon By Rosa Elena Carrasquillo Pompano Beach: Caribbean Studies Press, 2014, 246 pages

The day Rafael Cortijo’s remains were put to rest in Puerto Rico in 1982, his admirers came out in full force to honor their tropical music hero one last time. But one man caught everyone’s attention as he walked in front holding the coffin over his head with both hands. To all the people who lined the streets, Ismael Rivera’s grief was evident, in this last tribute to the man with whom he had shared the stage and a long history of musical creation and hardship.

Few artists have captured the public’s imagination like singer Ismael Rivera, “Maelo,” a veritable legend of urban Puerto Rican music. His was a life of extremes, a dramatic journey both literally and metaphorically whose dramatic arch extended well beyond his lifetime. Tenacity, creativity and audacity were three of the traits that distinguished him from his peers. Today he is still revered as troubadour genius for his resourceful intonation and for his unique talent for improvisation. With Rafael Cortijo, his compadre and musical sidekick, he burst into the San Juan scene at a time of many cultural and economic changes that would come to define “modern” Puerto Rico, and their music became the sound of an era.

In The People’s Poet: Life and Myth of Ismael Rivera, an Afro Caribbean Icon, Rosa Elena Carrasquillo traces the life of Maelo, offering a nuanced interpretation of his rise and fall as lead singer for the ensemble Cortijo y su Combo as a metaphor of post-colonialism in the Caribbean, and Puerto Rico in particular. She follows his evolution from childhood in Santurce (Musical Cradle 1931-1954); his rise to stardom (The Golden Years 1954-1962); troubles with the law (Imprisoned 1962-1966); incursion into the emerging salsa scene (Salsa Heights 1966-1979); and final curtain call (Desolation 1979-1986). Santurce is a storied neighborhood where runaway slaves took refuge in the 17th century and infused their new-found community with strong musical practices. By the 20th century, Santurce had become San Juan’s first suburb, a very dynamic neighborhood with cultural diversity and richness. Life in Villa Palmeras, the modest section where Maelo grew up and spent the better part of life, was infused with musical rhythms rooted in African traditions like bomba and plena. Maelo learned how to build barriles and panderos, the two percussion instruments used in these two popular genres in which dancers and drummers constantly improvise. This was the foundation upon which he built his artistic career.

Maelo’s mother Margarita initiated him in music. Through interviews and archival research, Carrasquillo takes a close look at this family, revealing how intimate influences played a crucial role in his sensibility.

In 1954, Maelo and Cortijo soon joined forces in Conjunto Monterrey where Cortijo played bongos and Rivera, congas. Maelo gained a reputation as a clever lead singer with much creativity in improvisation. After a short stint in the U.S. Army, he returned home to become the lead singer for Orquesta Panamericana and shortly after rejoined Cortijo in his new Combo and went on to reach stardom traveling with the band to New York, Europe and South America.

At the same time this was happening, Puerto Rico underwent a dramatic transformation led by industrialization and by the development of tourism as a magnet for economic growth. Beachfront hotels with casinos were built, and the island was promoted as a tourist destination in the U.S. market with great success. Yet, for all the talk of modernization, people of color were not allowed in ballrooms and most hotels. Musicians had to enter through the service door. Cortijo y su Combo, however, challenged convention as they clearly defined themselves as mulatos and were in very high demand. They began playing in hotels, and with the advent of television became regulars in variety shows conquering the public with their unique sound. Crowds adored their original and defiant approach to plena and son. No other group had achieved so much fame in an island with such pervasive racism. They tested established prejudice and found extraordinary support in the general public. But when Ismael was arrested and charged for drug possession as the band was returning from playing in Panama, he and the band quickly fell from grace, experiencing a devastating blow to their popularity. Maelo served a four-year sentence.

After being released, he formed a new band, Ismael Rivera y los Cachimos. But things were not the same. Although they played for eight years and recorded some of his most memorable songs (written by Tite Curet Alonso), his life was irreparably broken.

Carrasquillo’s book approached Maelo’s biography not simply as that of an artist fallen from grace by his fame and fortune but that of a creator whose work brought down barriers in terms of social class and race. In her words, “Ismael illustrated a type of hero of postcolonial times in which heroism abandons patriotic martyrdom for daily survival. Particularly on an island where the U.S. Congress ultimately controls politics, Puerto Ricans give great significance to the realm of daily routines and culture as it is the only allowed possibility for imagining a nation.”

Pedro Reina Pérez, a historian, journalist and blogger, was the 2013-14 DRCLAS Wilbur Marvin Visiting Scholar. He is a professor of Humanities and Cultural Agency and Administration at the University of Puerto Rico. Among his books and edited volumes are Compañeras la Voz Levantemos (2015), Poeta del Paisaje (2014) and La Semilla Que Sembramos (2003). More of his work at www.pedroreinaperez.com

Related Articles

A Review of Live From America: How Latino TV Conquered the United States

The story of Spanish-language television in the United States has all the elements of a Mexican telenovela with plenty of ruthless businessmen, dashing playboys, sexy women, behind-the-scenes intrigue and political dealmaking.

A Review of The Power of the Invisible: A Memoir of Solidarity, Humanity, and Resilience

Paula Moreno’s The Power of the Invisible is a memoir that operates simultaneously as personal testimony, political critique and ethical reflection on leadership. First published in Spanish in 2018 and now available in an expanded English-language edition, the book narrates Moreno’s trajectory as a young Afrodescendant Colombian woman who unexpectedly became Minister of Culture at the age of twenty-eight. It places that personal experience within a longer genealogy of Afrodescendant resilience, matriarchal strength and collective struggle. More than an account of individual success, The Power of the Invisible interrogates how power is accessed, exercised and perceived when it is embodied by those historically excluded from it.

A Review of Negative Originals. Race and Early Photography in Colombia

Negative Originals. Race and Early Photography in Colombia is Juanita Solano Roa’s first book as sole author. An assistant professor at Bogotá’s Universidad de los Andes, she has been a leading figure in the institution’s recently founded Art History department. In 2022, she co-edited with her colleagues Olga Isabel Acosta and Natalia Lozada the innovative Historias del arte en Colombia, an ambitious and long-overdue reassessment of the country’s heterogeneous art “histories,” in the plural.