A Review of The Remarkable Reefs of Cuba: Hopeful Stories From the Ocean Doctor

It feels as though work takes up more and more of our lives, expanding into time it never used to touch. As I sat on my couch early on Saturday mornings these past months, my kids beside me watching “Wild Kratts” or “Paw Patrol,” I was repeatedly faced with a decision: did I want to read David Guggenheim’s The Remarkable Reefs of Cuba or Patti Smith’s memoir, Just Kids? The former had a deadline, a flexible but tangible deadline for writing this review, a review I was asked to write in my professional capacity as a coral reef ecologist. Work. The latter I was reading for fun.

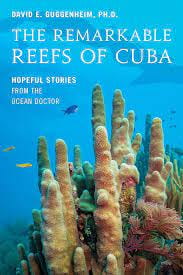

The Remarkable Reefs of Cuba: Hopeful Stories From the Ocean Doctor by David E. Guggenheim (Buffalo, New York, Prometheus, October 1, 2023, 264 pages)

I was asked to review the book because I know its scientific content quite well. Lines written in the book I had spoken to my students, almost verbatim, days prior: “Corals themselves compete for space using a type of chemical warfare against one another, and biochemical and medical research is focused on learning from this process and finding chemicals that could target cancer cells.” Yet, as I read on those Saturday mornings, I began to feel that my expertise did not matter as much in my evaluation as one might expect.

I devalued my expertise because my sense of the goal of this book, and many others like it, is to make people care more deeply about the loss of nature, rather than teach the reader something new. This literary approach is driven by the fact that nature is declining all around us, we need action to stop it, and action is not often stirred by facts and figures, but instead by tapping into something deeper to our being. If I’m correct, then I am not the target demographic—I already care deeply about coral reefs and their global decline due to overfishing, pollution, and climate change. A better reviewer may be my mother, an architect who cares deeply about climate change but doesn’t know reef ecology, or perhaps even better, my mother-in-law who cares deeply about animals but has never communicated a particular concern for climate change.

With these thoughts in mind, I found myself viewing The Remarkable Reefs of Cuba on a more fundamental level—was Guggenheim able to grab a broad audience and keep them in his world, rather than having them tire of the science and return to a more personal narrative, such as that in Just Kids. I began to see my read of the book as a litmus test: if The Remarkable Reefs of Cuba could engage me, someone who cares about reefs and knows the science, it would probably engage others who do not.

Many books describing the human-caused downfall of nature fit within the Silent Spring canon. Rachel Carson’s defining 1962 book was extremely effective because it was the first, because it brought a certain shock value, and because she was a gifted writer. It was a story that made us feel something—a mother bird, like that found in children’s books (remember Are You My Mother?) accidentally breaks her egg by merely caring for it, an upsetting event even to those with little interest in birds. Some authors have applied this literary approach to the ocean—Empty Ocean, for example, describes in great detail how and why charismatic marine creatures have gone extinct at the hands of humans. Other books tell a similar tale: humans are destroying the ocean, so we must do something to reverse course.

Unfortunately, doom and gloom are not very motivating. This reality drove Nancy Knowlton, a renowned coral ecologist, one of my mentors, and a recurrent character in Guggenheim’s book, to start a group called Ocean Optimism. Her goal was to share positive stories about the ocean, to tell people where and why things have improved so they know there are reasons for hope. Guggenheim chose a similar path in the way he wrote this book. He tells a compelling and complicated story of human suffering and environmental decline in Cuba with some positive outcomes for people and coral reefs. It is a reminder that the Dr. Seuss story of The Lorax, the utter loss and devastation of an entire ecosystem, has not manifest everywhere coral reefs are found.

Guggenheim describes Cuba as a fortunate mistake. Trade embargoes isolated the nation from many spoils of industrialization that are harmful to nature. For example, Cuba did not have access to copious amounts of industrial fertilizers, which are helpful for farming and golf courses but destroy coral reefs when rain drags them from land to sea. The island also avoided environmental destruction resulting from mass tourism. Guggenheim points out that the Caribbean has experienced extreme cultural homogenization due to mass tourism and financial leakage, or the loss of tourist dollars to other places. Only 20 cents of every dollar spent in the Caribbean stays in that country. Guggenheim worries that an opening of Cuba may lead to the same fate there.

As I read further, I found myself wanting to know more about Guggenheim the man. In the beginning of the book, he describes growing up middle class in Philadelphia. We learn little more about him until we read the lofty titles he has held, such as vice president of an international NGO called The Ocean Conservancy. This gap in time left me wondering about his successes and failures beyond his experiences in Cuba chronicled in the book. Herein lies what I find to be a critical element of popular science books that many authors overlook: people want to read about people. I have written about my experiences conducting reef research on Curaçao, an island in the southern Caribbean. My writing elicits the same response from nearly everyone who reads it: “I want to meet Oscar!” they say, referring to the elderly fisherman whom I hung out with while my colleagues dove to collect coral eggs and sperm. It’s not that my readers don’t care about the science, but what really resonates with them, with all of us, are the experiences of other people. Guggenheim profiles numerous Cuban colleagues throughout the book, but the people seem like window dressing on the science, and I wanted it to be the opposite.

In the end, I am not critiquing Guggenheim’s book so much as using the text to reflect on the larger topic of how science-minded authors motivate people to care about the planet. Guggenheim’s book does a wonderful job of pulling back the curtain on Cuba, explaining why it’s special ecologically and culturally, and placing the humans who rely on coral reefs in amongst the science and history. As I continued to read, I found myself pausing less and less on Saturday mornings. Soon, The Remarkable Reefs of Cuba was my preferred book, even in my capacity as a tired dad sitting on the couch drinking coffee with his kids, far from my office and even farther from the tropical coral reefs I study. The book passes my litmus test, a bar that is admittedly high and set by someone who is hard to impress, so I imagine that you will like it, too, whether you’re a coral biologist or someone who might be open to caring about our planet’s coral reefs.

Aaron C. Hartmann is a marine ecologist in Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University. He currently leads projects in Puerto Rico and Madagascar leveraging nature’s resilience to rebuild coral reef ecosystems and support the amazing people who depend on them.

Related Articles

A Review of Authoritarian Consolidation in Times of Crisis: Venezuela under Nicolás Maduro

What happened to the exemplary democracy that characterized Venezuelan democracy from the late 1950s until the turn of the century? Once, Venezuela stood as a model of two-party competition in Latin America, devoted to civil rights and the rule of law. Even Hugo Chávez, Venezuela’s charismatic leader who arguably buried the country’s liberal democracy, sought not to destroy democracy, but to create a new “participatory” democracy, purportedly with even more citizen involvement. Yet, Nicolás Maduro, who assumed the presidency after Chávez’ death in 2013, leads a blatantly authoritarian regime, desperate to retain power.

A Review of Las Luchas por la Memoria: Contra las Violencias en México

Over the past two decades, human rights activists have created multiple sites to mark the death and disappearance of thousands in Mexico’s ongoing “war on drugs.” On January 11, 2014, I observed the creation of a major one in my hometown of Monterrey, Mexico. The date marked the third anniversary of the forced disappearance of college student Roy Rivera Hidalgo. His mother, Leticia Hidalgo, stood alongside other families of the disappeared organized as FUNDENL in a plaza close to the governor’s office. At dusk, she firmly read a collective letter that would become engraved in a plaque on site. “We have decided to take this plaza to remind the government of the urgency with which it should act.”

A Review of A Promising Past: Remodeling Fictions in Parque Central, Caracas

A beacon of modern urban transformation and a laboratory of social reproduction, Parque Central in Caracas is a monumental enclave of 20th-century Venezuelan oil-fueled progress. The monumental urban structure also symbolizes the enduring architectural struggle against entropy, acute in a country where the state routinely neglects its role in providing sustained infrastructural maintenance and social care. Like other ambitious modernizing projects of the Venezuelan petrostate, Parque Central’s modernity was doomed due to the state’s dependence on the global oil economy’s cycles of boom and bust.