A Search for Justice in El Salvador

One Legacy of Ignacio Martín-Baró

In the small rural town of Arcatao, Chalatenango, Rosa Rivera clung to the hope that one day she would find the remains of her disappeared mother and father and lay them to rest in peace. Others sought to exhume mass graves hoping to recover bodies of nearly 1,000 relatives massacred in the Río Sumpul. Centro Bartolomé de las Casas (CBC) accompanied Rivera and other survivors on journeys of truth-telling and justice-seeking that include exhumations of clandestine cemeteries, healing rituals and reburials. They constitute just one example of work supported by the Ignacio Martín-Baró Fund for Mental Health and Human Rights, furthering the development of small group’s psychosocial training, organizational capacity and financial resources. This is not an abstract cause for us, as we both actively work with the fund.

We met each other for the first time in New York City at a conference commemorating the 25th anniversary of the assassination of the Salvadoran social psychologist and Jesuit priest, Ignacio Martín-Baró, whose ideas have opened new horizons for the field of psychology in El Salvador and across the globe.

I (Lykes) had met Martín-Baró in Cuba in 1987 during the XXI Congress of the Interamerican Society of Psychology (SIP). I was struck by his presentation on “lazy Latinos.” He challenged us as psychologists to deconstruct this commonplace, demeaning description of Salvadoran peasants that, despite its kernel of “truth,” obscured economic and power inequities that underlay assumptions about Salvadoran labor and this labeling process.

At these meetings I savored his humor, his guitar playing, and the urgency with which he engaged in gatherings some of us had organized to discuss forming a transnational network of activist psychologists committed to accompanying local Latin American communities build knowledge “from the ground up.” I could not have imagined then or in subsequent gatherings with him in Boston and Berkeley that these schemes and dreams would be cut short by the actions of the U.S.-trained Atlacatl Battalion two short years later.

Just a week after I (Portillo) turned 15, San Salvador was occupied in the largest offensive launched by the guerrilla forces in November of 1989. I never met Martín-Baró, but I remember TV coverage that included his dead body and those of his Jesuit brothers on the grass at the University of Central America (UCA). Four years later, I began my studies in psychology at the UCA. I studied Martín-Baró’s writings and learned about his life through surviving colleagues and commemoration acts on campus. I was drawn to his ideas and particularly to his proposal for a psychology of liberation, which voiced the need to construct a psychology that responds to the needs of the oppressed.

We, the two authors, reconnected in Boston where we are collaborating in the Martín-Baró Fund (www.martinbarofund.org). The fund was established in 1990 by a small group of psychologists, activists and advocates who sought to extend Martín-Baró’s liberatory psychology by supporting programs in the global south developed by and in communities affected by institutional violence, repression and social injustice. The fund seeks to encourage innovative grassroots projects that promote psychological well-being, social consciousness and active resistance by means of grants, networking, and technical support. Coordinated by an entirely volunteer group and housed at Boston College’s Center for Human Rights and International Justice, the fund has supported a total of 183 projects directed by 97 non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in 32 countries. A total of $1,090,878 has been distributed among these organizations.

Although small and limited in resources, the fund is one of the few sources of support for organizations in the global south whose understanding of and engagement with the effects of state-sponsored violence and gross violations of human rights is systemic and structural. These organizations recognize how important it is to accompany individuals and groups in addressing their suffering and its underlying conditions. The fund prioritizes projects in countries affected by U.S. political and military policies and practices, thus striving to critically educate the U.S. public about the use of its taxes and resources abroad.

Given the United States’ deep complicity in the armed conflict in El Salvador, the fund has provided support to 14 separate NGOs there; many have received small grants for several years. Community organizations and grassroots movements such as those supported by the fund have played a pivotal role in the recent history of El Salvador and the well-being of its people. Unfortunately their reach is usually limited, their life span is commonly short, and their experiences are rarely systematized. As a result, historical discontinuity is the norm and lessons learned are all too frequently lost.

In the new millennium, however, a fresh wave of community organizations has emerged seeking to continue the unfinished task of healing the deep wounds and ongoing social suffering in the Salvadoran society in the wake of the war there. One of those organizations is the Centro Bartolomé de las Casas (CBC, http://www.centrolascasas.org), founded in 2000 by a group of religious and community activists committed to the post-war reconciliation process. Just as Bartolomé de las Casas had advocated for the rights of indigenous people during the early years of the Conquest, the center began its work advocating for the survivors of the war who suffered its ongoing effects or what Martín-Baró had called psychosocial trauma.

Unlike the common understanding of psychological trauma—considered individual and nonpolitical—Martín-Baró sought to name and then respond to the collective experience of war that produced not only psychological wounds in individuals, but also—and above all— damages to the social fabric of entire communities. He suggested that trauma resides in relationships between the individual and society and emerges within an historical context; psychosocial trauma, he wrote, is “the concrete crystallization in individuals of aberrant and dehumanizing social relations.” He contended that mental health cannot be seen as separate from the social order, challenging psychologists to address not only the individual and social effects of war and other human rights violations, but also, in his words, to “construct a new person in a new society.”

Goals of the Martín-Baró Fund

1. To develop a holistic perspective for understanding the connections between state and institutional violence and repression, and the mental health of communities and individuals;

2. To support innovative projects that explore the power of community to foster healing within individuals and communities trying to recover from experiences of institutional violence, repression, and social injustice;

3. To build collaborative relationships among the Fund, its grantees, and its contributors for mutual education and empowerment; and

4. To develop social consciousness within the United States regarding the psychological consequences of structural violence, repression, and social injustice.

Since 2004, the fund has supported CBC in its psychosocial work with women survivors of massacres and families of victims in the rural communities of Arcatao, Nueva Trinidad and Perquín in the northwest part of the country for two three-year funding cycles. During this time CBC staff trained local community workers who accompanied survivors in their communities as they mourned those massacred and disappeared during the armed conflict and sought to rethread community. Group-based activities facilitated by CBC staff included creative play, traditional medicines and acupressure.

CBC also provided psychosocial accompaniment for the exhumation of remains. The exhumation work was done in collaboration with an experienced Guatemalan forensic anthropological team. In 2007, CBC inaugurated the Museo de la Memoria (Memory Museum) and published a community resource, Cuarenta Días con la Memoria: Memoria Sobreviviente de Arcatao (Forty Days of Memory: Survival Memory of Arcatao), as well as other testimonial materials.

Toward the end of the grant cycle provided by the fund, CBC was charting new directions, creating actions at the local, municipal, and national levels, demonstrating its work with survivors to justice authorities, landowners, and other committees. CBC workers had been invited to Chile and Brazil to share their experiences at international meetings on historical memory and mental health. In 2008, CBC staff visited Boston to participate in the fund’s Bowl-a-thon, its signature fundraising event, and had the opportunity to share firsthand reports on their project activities with members of the fund and with Boston College students.

More recently, CBC has added new programs in the areas of masculinities and peace-building among others. The educational and political campaigns of their Masculinities Program mobilize Salvadoran men to say no to violence against women, and yes to gender equity. It incorporates Martín-Baró’s concept of de-ideologization to expose cultural assumptions held by many Salvadorans about gender-based violence with the aim of constructing alternative forms of masculinity. CBC members have systematized and disseminated this experience in journal articles and other publications.

CBC is, in Martín-Baró’s words, constructing new people in a new El Salvador.

At the same time, CBC embodies the spirit of the work and political commitment of Ignacio Martín-Baró and remains one of the most successful partnerships that the fund has established in El Salvador. Defying the historical discontinuity that characterizes many community organizations, CBC has worked with Salvadoran men and women for more than 15 years to provide educational and psychosocial resources.

Working under extreme constraints and with meager budgets, community organizations in El Salvador and beyond are supported by funders and advocates who not only understand the goals of the grantees, but also work to accompany them on their journey to a more just society. The Ignacio Martín-Baró Fund exemplifies how small individual donations informed by pragmatic solidarity and the liberation psychology of its namesake can have a larger impact around the world.

M. Brinton Lykes is Professor of Community Cultural Psychology, Associate Director of the Center for Human Rights & International Justice at Boston College, and co-founder of the Ignacio Martín-Baró Fund. She also accompanies Mayan women and children and transnational and mixed-status migrant families in participatory and action research processes.

Nelson Portillo is a Salvadoran social psychologist and Assistant Professor of the Practice in the Counseling, Educational, and Developmental Psychology Department in the Lynch School of Education at Boston College. He joined the Ignacio Martín-Baró Fund in 2014 and currently serves as the chair of its Fundraising Committee.

Related Articles

A Search for Justice

In 2004, when I left Harvard and last saw you, I thought I would never learn the truth of what exactly happened to Carlos Horacio in the horrendous holocaust of the Palace of Justice in Bogotá. Yet fate was holding a tremendous surprise for my daughters and me, filled with…

Memory: Editor’s Letter

Editor's Letter Memory Irma Flaquer’s image as a 22-year-old Guatemalan reporter stares from the pages of a 1960 Time magazine, her eyes blackened by a government mob that didn’t like her feisty stance. She never gave up, fighting with her pen against the long...

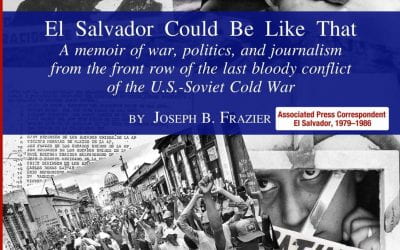

El Salvador Could Be Like That: A Memoir of War, Politics, and Journalism from the Front Row of the Last Bloody Conflict of the U.S.-Soviet Cold War

“There are no just wars. There are only just causes.” I was sitting in the modest home of a former FMLN guerrilla woman in a rural village in the northeastern corner of El Salvador. It was 2001, and I was nearing the end of my second year-long stint in this small Central American nation, interviewing more than 200 Salvadorans, mostly from rural areas, about their experiences during the civil conflict of the 1980s. …