Age of Enlightenment?

Comtemporary U.S. Policy in Guatemala

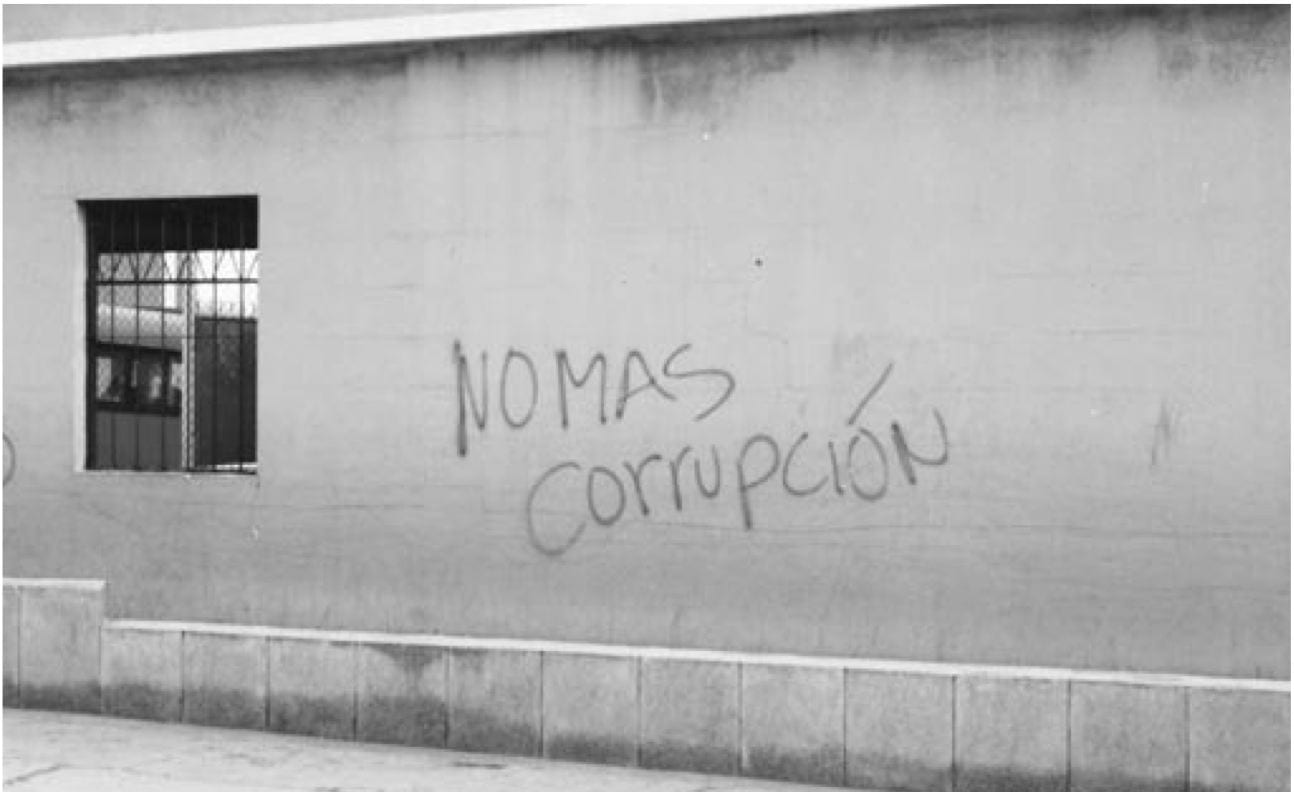

Graffitti on a Guatemala city building reads “No more corruption.” Photo by Michael Camilleri.

When in the early 1980s President Ronald Reagan sought the restoration of direct military aid to Guatemala, he praised the country’s leader Efraín Ríos Montt as “a man of great personal integrity.” Reagan brushed aside allegations that Ríos Montt’s scorched earth tactics had resulted in the mass murder of civilians, insisting that the military dictator was “getting a bum rap on human rights.”

Twenty years later Ríos Montt again sought the presidency of Guatemala, but this time the U.S. was unwilling to countenance the return to power of a man now known as the “Pol Pot of the Americas.” The State Department declared that the United States would find it “difficult” to work with the former strongman were he to win the 2003 Guatemalan elections (he did not). Though delivered diplomatically, the message from the Bush administration was clear: The United States opposed Ríos Montt’s bid for the presidency.

U.S. foreign policy in Guatemala has undoubtedly come a long, long way in the past two decades. The 1996 Guatemalan Peace Accords signaled not only the end of Latin America’s longest and bloodiest civil war, but also the dawning of a new era in U.S.-Guatemalan relations. The six major Accords, on issues such as human rights, indigenous rights, land distribution, the strengthening of civilian power and the resettlement of displaced persons, officially concluded 36 years of armed conflict between a leftist insurgency (the Unidad Revolucionaria Nacional Guatemalteca) and a right-wing government long supported by the United States. As recently as the early 1990s, the CIA was funneling $5 million to $7 million annually to the most notorious elements of the Guatemalan military. Such support was the legacy of four decades of Cold War policy-making, beginning with the CIA-sponsored overthrow of a democratically elected government in 1954 and continuing largely uninterrupted through a series of despotic regimes that squelched basic freedoms and carried out brutal counter-insurgency operations. This period of injurious U.S. influence came to a close with the 1996 Accords, and was repudiated three years later when President Bill Clinton issued a historic apology for the support provided by the United States to repressive military and intelligence units.

Today, U.S. priorities in Guatemala differ markedly from those of the not-too-distant Cold War past. Contemporary U.S. initiatives generally fall into one of three broad categories: development and governance, including USAID programming; free trade, notably the Central American Free Trade Agreement; and security, specifically efforts to combat drug trafficking, street gangs, terrorism and illegal immigration. This third category appears increasingly central to current U.S. policy, and these security concerns are certainly real.

Guatemala faces serious challenges in attempting to reign in violence and control its territory, and its difficulties with gangs, drugs, and other problems readily spill over into the United States. Nevertheless, U.S. policymakers’ focus on security issues comes at a time when Guatemala still urgently needs assistance building democratic institutions and fostering sustainable development. Income distribution in Guatemala is among the most unequal in the world. The country has disturbingly high rates of poverty (56 %), chronic malnutrition (49 %), and maternal mortality (153 per 100,000 births). Crime is rampant, the legal system dysfunctional, and public institutions subject to corruption and intimidation. The Peace Accords, a road map to a more democratic, inclusive, and equitable society, remain largely unimplemented.

These challenges and others must ultimately be addressed by Guatemalans, if they are to be addressed at all. There remains, however, an important role for the United States to play. Its participation in Guatemalan affairs is far more constructive than it was just a decade ago, but U.S. policymakers must maintain a strong focus on democracy, development and human rights if the United States is to continue influencing Guatemala in a positive way.

There are encouraging signs that United States officials, both at the State Department and USAID, understand the most important challenges faced by contemporary Guatemala. USAID’s country strategy acknowledges the potential for renewed crisis and conflict if the basic promises of the Peace Accords—namely broad-based economic growth and fair political and legal processes—are not delivered. The Agency’s programs focus on issues such as representative governance and the rule of law, indigenous participation, improvements in health and education, and rural economic diversification and growth. Unfortunately, the USAID mission in Guatemala recently experienced significant budget cuts, and Guatemala does not currently stand to benefit from either of President Bush’s major foreign aid initiatives: the Millennium Challenge Account and the Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief.

For its part, the State Department has maintained a strong focus on promoting the rule of law in Guatemala, with the notable exception of its active opposition to Guatemala joining the International Criminal Court. In May of 2004 the U.S. Embassy announced an agreement with the Guatemalan attorney general to provide technical and financial assistance to the special prosecutors for narco-trafficking, corruption, and money laundering. The State Department also provided steady support, and promises of funding, to a proposed U.N. commission (known as CICIACS) to investigate Guatemala’s so-called “hidden powers,” a shadowy network of powerful figures with connections to organized crime and top government officials. Guatemala’s highest court found aspects of the agreement creating such a commission to be unconstitutional, and the commission now faces an uncertain future.

Finally, the State Department has revoked the visas of more than 200 Guatemalans suspected of crimes such as corruption, drug trafficking, human smuggling, money laundering and murder. Visa revocation is a powerful shaming tool, and its targets have included former government ministers, military officers and bankers. In a country where impunity for the powerful is the norm and only about one crime in ten is ever solved, efforts by the United States to promote the rule of law are welcome and significant.

The highest profile U.S. foreign policy initiative in Guatemala today is probably the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA). The United States, Guatemala, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras and El Salvador signed CAFTA in May 2004, and the Dominican Republic joined the agreement in August. If ratified by the U.S. Congress—by no means a certainty given strong opposition by U.S. labor groups—CAFTA would remove tariffs and reduce other barriers to trade in a wide range of goods and services. CAFTA has been greeted by the conflicting assertions that inevitably surround the announcement of a free trade agreement. Supporters in the U.S. and Guatemalan governments and in the Guatemalan business community herald the accord as a boon to foreign investment and economic growth. Detractors argue that the agreement in fact encourages a “race to the bottom,” on environmental and labor standards for example, as countries cut costs in an effort to attract foreign investors. The result, opponents contend, is not long-term growth but short-lived gains that are unsustainable and narrowly distributed.

While debates about the virtues of CAFTA will undoubtedly continue, few would suggest that the agreement will not have any effect: The United States is Guatemala’s most important trading partner, providing 40% of its imports and purchasing 36% of its exports.

Increased competition will provoke a restructuring of the Guatemalan economy as some sectors thrive and others suffer, with benefits concentrated in urban areas and costs borne chiefly by small farmers. To its credit, USAID is seeking to identify and develop niche agricultural markets for Guatemalan farmers. Still, the immediate economic impact of CAFTA on Guatemalans’ lives is uncertain, and the government will have to cope with a not insignificant loss in tariff revenue equivalent to one-half of one percent of GDP.

If there is a silver lining in the agreement, it may be the potential for positive externalities in business practices stemming from a reduction in monopoly. The accord would give U.S. firms greater access to Guatemala in areas such as financial services, telecommunications, insurance, energy, engineering and construction. A business environment replete with firms subject to U.S. disclosure requirements and the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act could, at least in theory, result in greater levels of fiscal transparency and lower levels of corruption and tax evasion in the Guatemalan private sector.

While CAFTA may be the most prominent U.S. initiative in Guatemala at present, national security interests have been increasingly central to United States foreign policy since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001; bilateral relations with Guatemala are no exception. U.S. security concerns in Guatemala broadly encompass traditional worries such as illegal immigration and narco-trafficking as well as newer concerns such as terrorism and street gangs. A recent report by Latin America policy groups in Washington shows that U.S. officials working on Latin America—the bulk of whom are employed by the military’s Southern Command—are tending to lump the solutions to these problems into a strategy known as “effective sovereignty.” Pointing to the porousness of national borders, the lawlessness of city slums, the prevalence of drug and arms trafficking, and the potential ease with which terrorists might operate undetected, proponents of the effective sovereignty doctrine argue that the ungoverned spaces of Latin America pose a threat to U.S. national security. The tactics they propose for extending the apparatus of the state to these areas often blur the lines between civilian and military responsibilities. In nations such as Guatemala, still struggling to draw a line between the civilian and military spheres after decades in which no line existed, the United States’ willingness to push for military solutions to law enforcement challenges is alarming.

There is little doubt that U.S. policymakers are justified in harboring concerns regarding Guatemala’s capacity for securing its territory. According to the State Department, 220 tons of cocaine passed through Guatemala in 2002 alone, more than two-thirds of Americans’ consumption of the drug. Guatemala’s northern border with Mexico is virtually lawless: Hundreds of illegal immigrants cross daily trying to reach the United States, police and plantation owners exploit those they encounter, gangs members assault, rob, and kill with impunity, and smugglers sneak across with guns, drugs, wood, cattle and rare animals. In Guatemala’s cities and towns, street gangs born in 1980s Los Angeles commit 80% of the more than 1000 gun killings each year; their cohorts drive crime in places like Southern California, Chicago, and suburban Washington, D.C. Finally, a suspected Al Qaeda member was recently alleged to have been spotted at an Internet café in neighboring Honduras, raising the specter of international terrorists using Central America as a staging ground for attacks on the United States

In response to “sovereignty” problems of the kind that plague Guatemala, United States officials have come to view military units and military tactics as part of the solution. In recent years the U.S. has trained Latin American military officers in civic action, trained civilian police in light infantry tactics, and provided almost as much military as economic aid to the region. This trend may soon extend to Guatemala. Though most funding for Guatemala’s military was still banned as of February 2005, the Defense Department and U.S. Ambassador John Hamilton have been pushing hard for its reauthorization. Privately, officials justify this push on drug interdiction grounds.

Though the 1996 Peace Accords limit the role of the Guatemalan armed forces to defending the country’s independence and territorial integrity, the Guatemalan government has already displayed a willingness to merge civilian and military security operations. In July of 2004, for example, President Oscar Berger ordered 1,600 soldiers to patrol the streets of the capital. Berger was understandably frustrated by the inability of an undermanned, under-equipped, and often corrupt police force to protect the public. U.S. officials were equally frustrated when a now disbanded anti-drug police unit was accused of stealing more cocaine from police warehouses than it had seized in raids. But the army—an admittedly tempting solution—remains a problematic institution. It has shrunk in size and shed some of its more notorious officers, but it maintains links to organized crime, balks at civilian oversight of its finances and offers scant assistance in the investigation of past abuses. The army’s reinsertion into domestic, civilian affairs threatens to undermine critical processes of democratization and demilitarization in Guatemala. In the long run, this can only be considered a security risk for the United States.

The pursuit of “effective sovereignty” over Guatemala’s lawless, ungoverned regions must instead prioritize the extension of government services such as courts, police, health clinics, schools, roads and agricultural services. Likewise, the lack of an effective police force should be addressed not by dispatching the military but by improving police training, equipment, salaries, and manpower. Gang membership and illegal immigration should be tackled by both improving law enforcement and expanding economic and social development programs. By cutting development funding while seeking to reauthorize military aid, the United States has sent Guatemala the wrong signals—prioritizing short-term security gains over the establishment of a strong democratic state. If U.S. officials can now reverse course and redouble their laudable efforts to promote democracy, development and human rights, we will truly have entered a period of enlightened United States foreign policy in Guatemala.

Spring/Summer 2005, Volume IV, Number 2

Michael Camilleri(J.D. ’04) is a Henigson Fellow at the Harvard Law School Human Rights Program and a lawyer with the Human Rights Coalition Against Clandestine Structures in Guatemala.

Related Articles

Introduction: Bush Administration Policy

So it is the policy of the United States to seek and support the growth of democratic movements and institutions in every nation and culture, with the ultimate goal of ending tyranny…

International Symposium in Puebla

It is likely that Don Quijote first reached the Western hemisphere—in what was, at the time, lightning speed—as a stowaway. On September 28, 1605, Franciscan commissioners of the…

Adiós 61 Kirkland

For the past eight years, the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies has made its home at 61 Kirkland Street. Countless film screenings, celebrations and roundtable discussions…