Aging in the Diaspora

Salvadoran Women Who Made Italy Their Home

Milan, Italy: Silvia Tobal prepares paper flower decorations at the Casa de la Cultura Salvadoreña in Milan, for the upcoming Flower Festival beauty pageant. Copyright © Donna De Cesare, 2018

La Deliciosa restaurant, just outside Concepcion Quetzaltepeque, El Salvador, tempts travelers with homemade gelato and pasta, as well as pupusas, tamales and other local favorites. Rosie Galdamez, the gregarious 34-year-old proprietress, spent almost eight years as a domestic worker in Milan before deciding to return to raise her Italian-born Salvadoran son near his grandparents in the village of her birth. Many, like Rosie, decide to come back to tend to seniors, but many Salvadoran seniors are choosing to age in the relative safety of the Italian diaspora.

“I have a sister in Italy who was supportive but the life there just wasn’t for me;” she says. “I suffered with so much nostalgia and work left little room for life. Here, you have family, friends and acquaintances close, not dispersed. And they have time for you. If you are sick they notice and they are generous. And I have my aging parents who need looking after as well.”

Uphill from Rosie’s restaurant, the road continues to climb overlooking cow pastures and fields of corn. Rows of traditional single-story adobe dwellings with terracotta-tiled roofs abut opulent edifices rising two and three stories. They seem incongruous, but I am reminded of Rosie’s nostalgia for home while she lived in Milan. These “villas” are emblems of diaspora success. They are also a peculiar embodiment of a common émigré desire—to return home to live an idyllic retirement in pastoral comfort with space for an abundance of guests, children and grandchildren.

Yet strangely, these casonas loom in empty silence, achingly forlorn, weathering as if aging before their time. A fleeting glance at newspaper headlines on any given day is sufficient reminder that tranquility in even the safest-seeming hamlet is fragile in El Salvador. The tentacles of roving gangs and other violent actors reach far and wide. They have made El Salvador once again a country that people flee for their lives—as many in Rosie’s village can attest.

Origins

Emigres seek safety in places where they are likely to find a familiar face and helping hand. Salvadoran migration to the United States dates back to the 1980s and El Salvador’s brutal civil war. That the elderly folks in Rosie Galdamez’s town have children in Los Angeles or Houston or Washington DC is unremarkable. What surprised me is how many also had family members in northern Italian cities and towns. I wondered just how long this Italian migration has been going on.

A year ago in Milan I began to find some answers. I interviewed three senior women, all community leaders who were pioneers from that first generation of Salvadorans who emigrated to Italy beginning more than a decade before the outbreak of the civil war. Silvia Tobal and Deidamia Moran knew each other slightly in El Salvador. They emigrated within a few years of one another in the early 1970s. Celia Landaverde (whom I was fortunate to meet before her passing on August 1, 2018), didn’t know either Tobal or Moran in El Salvador. They learned of one another by reputation and through the community work each did in Italy.

Milan, Italy: Silvia Tobal with Deidamia Moran on Mother’s Day at the Oscar Romero Community celebration at the Shuster Center in Milan Copyright © Donna De Cesare, 2018

None of the women had worked in domestic service in El Salvador. None had travelled extensively in her own country before traversing 6,000 miles from San Salvador to Milan alone, each on her own maiden journey by plane. Perhaps most consequentially, none of them spoke a word of Italian. Given the exacting scrutiny they would face as live-in housekeepers, this may have been a partial blessing. Unfamiliar with the cuisine and its preparation, they were also unprepared for the expectation that chores conform meticulously to enigmatic criteria deemed a matter of common sense by their well-to-do northern Italian employers.

Finding other Salvadorans in their limited hours of weekly respite became essential to lower stress and animate their survival. For all three women this necessity became a protector of identity and an impetus to get involved in community service and to fulfil their human potential.

Landaverde began to focus on migrant labor rights as a volunteer with the Italian National Association Beyond Borders (ANOLF), later working in an official capacity as a rights educator under its alliance with the Italian Confederation of Labor Unions (CISL). Tobal focused on building community through social and popular cultural events, founding the Casa de la Cultura Salvadoreña, to promote Salvadoran popular heritage including folkloric dance, marching bands, food and language. Moran, recognizing spiritual life as a cornerstone of Salvadoran identity,forged the Oscar Romero Community at the Shuster Center. This project both engaged diasporaimmigrants in support for newcomers, but sought to maintain their connection and assistance tothe communities they left behind in El Salvador, even as they themselves became more established in Italy. The Catholic Shuster center campus in the northeastern Lambrate district of Milan, afforded sports fields and space for celebratory events as well a modern chapel in which to worship Salvadoran style. In addition to Spanish language, the Sunday Mass and religious observances incorporated cultural practices, rituals and hymns familiar to Salvadoran Catholics.

The stories of how Celia Landaverde, Silvia Tobal and Deidamia Moran came to be recruited for work and built lives in Italy are individually impressive, but these women were also part of a significant trend. Salvadoran migration to Italy began as a female migration occurring at a time when women from other parts of the world were also arriving to fill a niche labor demand. The northern Italian industrial boom of the mid 20th century created new wealth and social mobility for the Italian middle class as well as for the established well-to-do families.

It also meant that women from Italy’s impoverished south who traditionally migrated north for work as live-in domestic service for the first time enjoyed expanding labor options. Many preferred factory work with its greater personal freedom and the superior pay, benefits and workers’ rights protections that resulted from unionized collective bargaining. As the supplyof Italian women seeking domestic work declined, the growing demand for “family collaborators” (the official designation for domestic service in the Italian labor code), opened the market tomigrant women.

Some employers began to see a financial advantage in hiring non-Italian labor. Although by law, foreign workers are entitled to the same rights and working conditions as their Italian counterparts, in reality women without language skills and knowledge of the law could be persuaded into arrangements of non-regulated informal employment. Without contractual protection and dependent on employers for lodging, an emerging class of unregulated clandestine workers were in the short term ripe for wage theft and/or abusive work schedules. In the long term, such clandestine arrangements would leave older workers without the safety net of social security. As those pioneering women of the early migration found, education, autonomy and self-care were indispensable for the paths they forged.

Celia Landaverde: Community Leadership and Immigrant Rights

Of the three Salvadoran Italian women profiled, Celia Landaverde arrived first in Italy. Born in 1948, she emigrated to the city of Milan in the late 1960s. “It was not for adventure or to look for opportunities, it was simply to survive,” Landaverde told me. As a child she was an avid student and attended a Catholic boarding school on scholarship. Just as she started 9th grade, however, her 37-year-old mother died. The impact was immediate. Celia Landaverde lost both the mother she loved and the education she craved. At age 14 she went to work assuming responsibility for her four much younger siblings. As the years passed her meager wages barely sustained them. She despaired of ever being able to honor her mother’s dying wish that all her children beeducated.

“I confided in Don Juan Masaya, one of the priests at the Calvary Church which was near the store where I worked and he promised to help,” Landaverde, recalled. The well-known church in San Salvador was run by the Somascans, an Italian missionary order. Through these priests,Landaverde made contact with the Italian family who hired her and arranged her travel. “We Salvadorans didn’t need a visa for Italy so I arrived as a tourist, on a plane ticket bought by the family that employed me. They met me at the airport and took me to live and work at their home,” she told me.

Landaverde toiled for her first three years in Italy without a legal work contract. Finally, she persuaded her employers to normalize her status in 1971. She continued caring for the family’s three children for the next two years, sending what she saved by living with them to El Salvador to support her siblings and their schooling. But she found that the hours and demands of “live-in service,” even if compensated to full requirements of Italian law, still frustrated her desire to attend night school. She continued to do domestic work, but sought to work an eight-hour daily schedule. Some nuns helped her find a private room to rent. Landaverde began taking classes and spending her weekends as a volunteer with Catholic Charities setting a course that led todecades of work as a union activist focused on immigrant integration and labor rights.

At first when people suggested I work with the unions I was afraid and in my ignorance tried to steer clear of them. I carried memories from El Salvador where everyone feared association with unions, because of the repression,” she explained. “But I learned that I was wrong. I started seeing how people were being abused by the clandestine labor system here. I complained to the police, but nothing happened. I couldn’t just close my eyes. It took time but finally my work with ANOLF as a volunteer led to my salaried work as an educator for the union.” Her work brought Celia Landaverde into contact with the diverse ethnicities and faith backgrounds of Italy’s immigrants. She worked equally for all, she told me. However, in the eyes of the Salvadoran community she remained their own pioneer and a trusted advisor.

The last time I spoke with Celia Landaverde was at the end of May 2018, two months before she passed away. She was at a life skills workshop for immigrants promoting social integration and civic awareness. Despite her declining health, in retirement she continued to counsel immigrants on residency requirements and regularly attended training events organized by the International Women’s Group (GDI) an ANOLF affiliate which she founded and presided over as president for 40 years.

Milan, Italy: Celia Landaverde (center) attending a workshop training of the International Women’s Group (GDI) which she founded and presided over as president for 40 years. The banner behind Celia Landaverde is the emblem of the National Association of All Ages for Solidarity (ANTEAS) which is an affiliate of the retired workers of Italian Confederation of Labor Unions CISL. ANTEAS provides space in their offices for other organizations to hold meetings and workshops. Celia’s group has been meeting here since her official retirement from CISL. Copyright © Donna De Cesare, 2018

It wasn’t long before a queue had formed. Well-wishers embraced her and shouted greetings; others solicited advice. With a professorial flourish she batted the compliments away as if swatting flies, but clearly relished her role and the display of regard. She huddled with an anxiousman who feared being stranded in France if he travelled there with his employer and his expired resident permit. He was visibly relieved as Landaverde proffered a solution. “But you must act quickly,” she said smiling while shaking her finger. Toward the end of the evening a tearful young woman, a former prosecutor who had received death threats in El Salvador, approached with a bouquet of flowers. As they embraced the woman exclaimed: “Doña Celia you saved my life. I want everyone to know that today because of your advice and support I learned that my asylum request has been granted.”

Silvia Tobal: Preserving identity for the next generation

When Silvia Tobal left San Salvador for Italy on September 7, 1972, she was 24 years old. “Looking back I think how completely unprepared I was,” she said. “The only thing I knew was that I would be caring for an elderly Italian woman.” The job offer had come through Silvia’s friend Christina Rosales who was working for a family in Italy. Christina’s employer had passed Silvia’s name to a family friend who wanted someone reliable willing to commit to a three-year contract. Three years seemed a lifetime to Tobal, but Christiana begged her to come and the pay was many times what her job at the Armed Forces Cooperative in El Salvador paid. Tobal was helping to support her younger sisters so she agreed. Then almost as soon as she arrived in Italy, Christina, who was the only person Tobal knew there, decided to go back to El Salvador.

Living completely enclosed in someone else’s world, on call except when sleeping and without language to communicate or the comfort of familiar food was devastating. “I never have felt so alone. I cried every day and I hardly ate,” Tobal recalls. “It was years before I ever saw a guineo [a variety of banana that is a staple in Salvadoran cuisine] or tasted our blessed little red beans which I ate every day at home. Imagine,” she sighs.

The absence of everything Tobal felt defined her identity—food, language, music and dance – left a mark and fueled her determination to create the Casa de la Cultura Salvadoreña, which she founded in Milan more than a decade ago. “People need to socialize, to have fun, to laugh,” she says. “When we Salvadorans finally found each other after those first years of solitude it was our fiestas that made life bearable, helped us survive the stress. And it kept us young,” she laughsgesturing coquettishly.

Milan, Italy: Silvia Tobal working at the Casa de la Cultura Salvadoreña in Milan, the organization she founded in 2007 to support young people and promote popular traditions of Salvadoran food, language, dance and music. Copyright © Donna De Cesare, 2018

Tobal says the stresses are different now. “The young men, women and children, coming to Italyhave more education than our generation,” she explains. “But they arrive traumatized by the unbearable violence at home.” Without a diploma from an Italian University or an Italianvocational training certificate, finding work at parity with work they may have been doing in El Salvador is next to impossible. Parental anxieties over downward social mobility have an emotional impact on children who also must contend with a new language at school.

But even for the children of the second generation, who are growing up in Italy now, it can be hard to fit in. Tobal explains, “They know they don’t look the same as the Italians. But they never hear anything good about El Salvador. So they just try to be invisible.” Tobal knows that invisibility breeds frustration. She recalls such feelings from her own isolating early experience and from the charitable voluntary work she did assisting the homeless or visiting the incarcerated, which she began doing in her free time in 1992. Her focus since 2007 has been on youth. “That’s why I tell their parents, bring them to the Casa de la Cultura.” The boys love the marching band and learning to play the trumpet or drums or trombone. For the girls, twirling with the band or learning folkloric dance makes them feel special. “It helps the shy ones to speak up. It builds confidence and pride when they know who they are.” Tobal says, adding, “And it keeps them out of trouble too.”

Tobal tells me that she knows she should slow down. The arthritis in her knees is so painful thatshe sometimes finds she must use those hated forearm crutches that her doctor recommends. Her nieces tell her she deserves to rest; she’s done enough to help other people. However, without a clear successor in the wings to run the Casa that she built, Tobal says she feels a responsibility to continue. Yet watching her in action it is clear that it is not only obligation that keeps her arranging festivals and events.

“The young women would be so disappointed if we no longer had the “Fiesta de las Flores,” Tobaltells me. I don’t doubt that the eager teenagers I’ve seen participating with such gusto in modern dance, folkloric dance, or modeling evening wear as they compete to be crowned the festival Queen would miss this. They and their mothers were clearly having such fun on the day I spent with them. But as I glance over at Silvia I see that she is enthralled. The young Salvadoreña who began life in Italy alone caring for an elderly Italian thrives in her rooted Italian years as a creator of moveable feasts dancing the night away with Salvadoran youth.

Milan, Italy: Silvia Tobal at Casa de la Cultura’s Flower Festival. “The young women would be so disappointed if we no longer had the “Fiesta de las Flores,” Silvia says. Copyright © Donna De Cesare, 2018

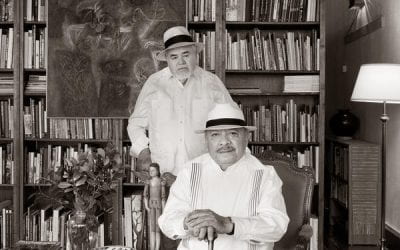

Deidamia Moran: The Soul of a Community

The intersection of the global migration story and greying demographics in receiving countries like Italy or the United States is a fairly new area of scholarly research. In a climate of anti-immigrant resentment, it is significant that studies demonstrate the essential contributions that immigrants make to an aging economy’s overall health as well as to niche labor sectors like the expanding elder care industry. Less studied or understood are how immigrants who care for the elderly Italians fare themselves as they grow older, or how the migration of productive workers impacts the older generation left behind in the societies those workers leave.

For the immigrant women who traveled to work in Italy in the 1970s, an Italian social security pension is often not enough to sustain retirement. “The women of my era didn’t think about saving or planning,” Deidamia Moran tells me. “We had lived in grinding poverty in El Salvador, so we felt motivated to send our money to ease the suffering there. In Italy we lived where we worked. We wore clothes we were given. We’d go home to El Salvador when the contract expired, when we saw there was still so much need, we’d come back to work more. We educated and gave comforts to our families. We never thought about growing older ourselves. Because of this some who are retirement age cannot stop working. They remain without a home to call their own here or there.”

Born in Tonacatepeque in 1946, Moran was raised by a loving grandmother, but in dire circumstances. Determined to get an education, she migrated at 18 to El Salvador’s capital, San Salvador. There she reunited with her long absent father, a stepmother and two younger siblings. She worked by day and studied by night until she finally earned a nurse’s aide certification. She was working at the Bloom Children’s Hospital when her friend Silvia Tobal who had gone to Italy two years earlier wrote in 1974. Tobal had been asked to refer someone to work as a housekeeper outside Milan for a family her employer knew.

Moran was then 28 years old, fiercely independent and confident in her abilities. Like Tobal before her, Moran made calculations. “They were offering a legal contract of 65,000 Italian lira which at the time was the equivalent of $100 a month. I earned 150 Salvadoran colones an hour as an auxiliary nurse at the Bloom Hospital in 1974 (roughly $9.60 a month.) I looked at this exchange rate and realized I’d earn in a month almost what I made in a year,” she recalled. She thought of what her savings could mean for her siblings and didn’t hesitate. She embarked on a journey thather employment history had not prepared her for, but that would in time change the focus of her life and provide some economic security.

During the handful of free hours per week they had in those first isolating years, Tobal and Moranbegan to hear about other Salvadoran women in Gallarate, the small city outside Milan where they were working. They had nowhere they felt comfortable meeting and the cold weather and their rigidly scheduled handful of hours off conspired against organized activities. “We had to ask permission for everything,” Moran recalls. “Bending the rules whenever I could is what saved my sense of control.”

Moran was not very religious in those early years but with the 1980 murder of Monsignor Romerothe Salvadoran archbishop, (now Saint Romero) who defended the poor and implored El Salvador’s military to halt the repression, she felt a deep loss. Her friend Sofia Palacios invited herto a mass in nearby Varese with a community of nuns from the congregation Servants of St. Joseph. “Sofia and the Salvadoran community there became an anchor,” Deidamia recalls.

Gallarate, Lombardy, Italy: Deidamia Moran and Sofia Palacios revisiting places and memories from their first years working in Italy in the 1970s. The main plaza in Gallarate is near where both women first met one another. Copyright © Donna De Cesare, 2018

Later that same year, the civil war took the life of Moran‘s adored younger brother. “I was consumed by sadness and rage,” she says. Her own crisis heightened her sensitivity and awareness of the anguish the civil war in El Salvador was causing others in the community. “People began bringing sisters and brothers and husbands to Italy, for safety, but also to help those left behind,” Moran recalls. It was from within this crucible that Moran found her direction. “The nuns in Varese used to care for Italy’s internally displaced—the southern Italian women who once migrated to do domestic work in the north. They opened their doors to the Salvadoran community without interference so that we could hold our own meetings and celebrations. We finally found a space to feel a little piece of home. It was the place where I finally began to learn about my own country’s history and where my communitarian ideas were born.”

Moran left life in domestic service in 1985 and moved to Milan where she established a small cleaning company which she owned and operated for 25 years. In 1986 she was elected President of Milan’s first legally constituted Salvadoran Community. Through her continuing voluntary community efforts, the Catholic Shuster Center agreed to open its doors to Salvadorans providing a place for meetings, celebrations and Catholic religious observance. Eventually in 2007 it became officially recognized as the Salvadoran Community Monsignor Romero in Milan. With the support of a broad network of immigrant organizations in Milan, Moran was named Woman of the Year 2007 by the Milan Mayor’s Office for her many years of service to immigrants’ rights and promoting advancement of women in business and in community leadership. In 2011 the Salvadoran Ministry of External Affairs bestowed on her its first recognition for Distinguished Salvadoran citizen resident outside El Salvador.

Although she is technically retired, Moran continues to work at a sports complex as part of the logistical team. She enjoys the work not least because it has kept alive the warm bond offriendship she first established with the Vero Volley Consortium owner Alessandra Marzari back in the 1970s. In her teen years Marzari often visited her aunt’s home in Gallarate, where Moran wasemployed for the first decade she spent in Italy. “I think that since I was born I was born to protect,” Moran says. “The only person that protected me was my grandmother. So I know the consequences of receiving and not receiving affection,” she continues. “Alessandra trusts me and I trust her. So the friendship and working relationship work for us both.”

Recently Moran helped another old friend. Sofia Palacios was having a hard time finding an apartment she could afford on her meager social security pension. Accustomed to living in service for most of her adult life, it was also clear that Palacios was a little apprehensive about living on her own. As she has done throughout her life, Moran took charge and found an apartment back in Gallarate that made economic sense for Palacios, and also would allow her to be in familiar surroundings near some old friends who still live there, as well as access to visit the Romero community for Mass or special celebrations. The last time I saw them together they were moving some of Palacios’ belongings to her new home and enjoying a day of reminiscences and laughter. Looking back at the lives they left, they realized that they had built lives they could not have imagined when they first met so many years earlier.

Fortunately, for these pioneers, their own socialization equipped them with the very skills that the Italian society that would receive them sought. Unlike Northern Europe, where by the mid- 20th century state welfare structures were expanding to support women’s participation in the labor force with heavily subsidized formal childcare and eldercare options, the Mediterranean model clung to a reliance on informal extended familial support. Notwithstanding, strides in women’s rights, an unresolved tension between the productive and reproductive roles of Italian women continues to this day. The persistence of robust gendered roles within many Italian families stems in part from the complex influence of Catholic doctrine and values stressing the primacy of the family and the maternal role within it. It was a social construction that the Salvadoran women found familiar.

Given El Salvador’s significant Catholic culture and the presence of Italian priests in foreign missionary postings, it is unsurprising that the Church should have played a role as a bridge in assisting women like Celia Landaverde to migrate. From the priest’s point of view, his assistanceperformed a morally honorable service of mutual benefit to the parties—enhancing the economic well-being or security of a needy parishioner with wholesome work in a “protected” family environment while supporting the integrity of Italian family life with an appropriate supplemental female caregiver. In both El Salvador and in Italy I met women who emigrated in the 1970s and men and women who migrated in 1980s with similar stories of being assisted by Italian Silesian, Franciscan or Somascan missionary priests.

Varese, Italy: Deidamia Moran meets with Sister Anna of the Servants of St. Joseph order, the congregation the first opened its doors to the Salvadoran community in the 1970s. “They opened their doors to the Salvadoran community without interference so that we could hold our own meetings and celebrations. We finally found a space to feel a little piece of home. It was the place where I finally began to learn about my own country’s history and where my communitarian ideas were born,” Deidamia said. Copyright © Donna De Cesare, 2018

The trickle of migration cases that began propelled by economic need and a niche labor demandgathered strength as Salvadorans began fleeing repression and later a brutal civil war. Once a migrant pathway establishes, it remains. People bring family or friends in need. There may be dips or increases in migration in response to labor market conditions or as motivations for leaving shift, but when faced with peril people flee even if there is perceived hostility in the receiving nation.

Celia Landaverde, Silvia Tobal, and Deidamia Moran never planned to stay in Italy. As diaspora experiences encouraged an expanded identity, each found her voice, became an Italian citizen and made Italy her home. Individually and collectively, their legacies of meaningful and graceful aging have made these women exemplary not only for Italy’s Salvadoran community, but for others who are enlarging identity and defying stereotypes that belittle and exclude.

Winter 2019, Volume XVIII, Number 2

- Milan, Italy Celia Landaverde answering questions at a workshop offering life skills and information on Italian integration to men and women of immigrant backgrounds. The training sponsored was sponsored by the International WomenÕs Group (GDI) which she founded and presided over as president for 40 years. Copyright © Donna De Cesare, 2018

- Milan, Italy Celia Landaverde (center) considers a question a training on italian integration sponsored by the International WomenÕs Group (GDI) which she founded and presided over as president for 40 years. The banner behind Celia Landaverde is the emblem of the National Association of All Ages for Solidarity (ANTEAS) which is an affiliate of the retired workers of Italian Confederation of Labor Unions CISL. ANTEAS provides space in their offices for other organizations to hold meetings and workshops. Celia’s group has been meeting here since her official retirement from CISL Copyright © Donna De Cesare, 2018

- Milan, Italy At the end of a workshop on Italian integration for immigrants a tearful Salvadoran woman a former prosecutor who had received death threats in El Salvador embraced Celia Landaverde with a bouquet of flowers and said: ÒDoa Celia you saved my life. I want everyone to know that today because of your advice and support I learned that my asylum request has been granted.Ó Copyright © Donna De Cesare, 2018

- Milan, Italia Silvia Tobal at Casa de la Cultura Salvadorea in Milan, the organization she founded in 2007 to support young people and promote popular traditions of Salvadoran food, language, dance and music. Copyright © Donna De Cesare, 2018

- Milan, Italy Silvia Tobal at her home with one of the original posters for DANFOSAL. They were first group of Folkloric Salvadoran dance that began in Milan Italy and in 1999 took the name Danfosal. (Danza Folklorica salvadorena) and would occasionally bring dancers from from the National Folkloric Ballet of El Salvador to Italy to do trainings. Providing a home for Salvadoran dance was a motivating force for creation of Casa de la Cultura Salvadorea in Milan. Copyright © Donna De Cesare, 2018

- Modena, Italy Silvia Tobal with the marching band, twirlers and two folkloric dancers traveling by bus to Modena Italy to perform during a weekend festival celebration of Latin American and Italian food. Copyright © Donna De Cesare, 2018

- Modena, Italy Case de la Cultura Salvadorea’s marching band, twirlers and folkloric dancers perform in Modena at weekend festival celebration of Latin American and Italian food. Copyright © Donna De Cesare, 2018

- Modena, Italy Case de la Cultura Salvadorea’s marching band, twirlers and folkloric dancers perform in Modena at weekend festival celebration of Latin American and Italian food. Copyright © Donna De Cesare, 2018

- Milan, Italy Silvia Tobal celebrates the birthday of Isela Portillo, the lead twirler for the Casa de la Cultura Salvadorea’s marching band in Milan. Copyright © Donna De Cesare, 2018

- Milan, Italy Silvia Tobal and her niece at the Shuster Center where the Oscar Romero Community hold a play as part of the annual Mother’s Day celebration. Copyright © Donna De Cesare, 2018

- Milan, Italia A mother helps her daughter prepare to perform in the folkloric dance exhibition at the Flower Festival organized by the Casa de la Cultura Salvadorea. Copyright © Donna De Cesare, 2018

- Milan, Italy Deidamia Moran with her special Salvadoran flag at her home in Milan Italy. She has become an Italian citizen and says that Italy has taught her important lessons and enriched her life. “I am a dual citizen, but my heart will always be Salvadoran,” Deidamia says. Copyright © Donna De Cesare, 2018

- Milan Italy Sofia Palacios, (right) at the commemoration procession and Mass on the anniversary of the assassination of Monsignor Romero at the Shuster Center. Copyright © Donna De Cesare, 2018

- Milan Italy Sofia Palacios, ( far right) at the commemoration procession and Mass on the anniversary of the assassination of Monsignor Romero at the Shuster Center. Copyright © Donna De Cesare, 2018

- Milan Italy Deidamia Moran serves communion at Shuster Center chapel during the Mass on the anniversary of the assassination of Monsignor Romero Copyright © Donna De Cesare, 2018

- Milan Italy Easter dinner celebration at Deidamia Moran’s home with some of her closest Salvadoran friends in Milan. Copyright © Donna De Cesare, 2018

- Milan Italy Deidamia Moran at the Holy Saturday Vigil at the Shuster Center with Father Mario Belladonna and community Monsignor Romero Copyright © Donna De Cesare, 2018

- Gallarate, Lombardy, Italy Deidamia Moran helped her long time friend Sofia Palacios find an affordable apartment in Gallarate, Italy, the town where they both met in the 1970s when they worked as live-in domestic workers. Sofia has no savings as she always sent her earnings to help her family members in El Salvador. In retirement she finds it difficult to make ends meet on her meager Italian pension. She relies on her old circle of friends like Deidamia who is helping her with furnishing and cleaning as she moves into the new apartment. Copyright © Donna De Cesare, 2018

- Gallarate, Lombardy, Italy Deidamia Moran listens as her long time friend Sofia Palacios explains some of the struggles she has been facing. The women are cleaning and arranging furnishings in the new apartment Deidamia helped Sofia find. Copyright © Donna De Cesare, 2018

- Monza, Italy Deidamia Moran with her long time friend and current employer Alessandra Marzari, President of the Vero Volley Consortium and sports complex in Monza. Copyright © Donna De Cesare, 2018

- Milan, Italy The patron saint and namesake of El SalvadorÑEl Salvador del Mundo (the Savior of the World)Ñis honored with a national festival and celebrated in diaspora communities. Deidamia Moran takes part in the religious procession which precedes Mass and then a large fair, sporting events and contests of varying kinds at the Shuster Center in Milan. Copyright © Donna De Cesare, 2018

- Milan, Italy At the feast for El Salvador’s patron El Salvador del Mundo (the Savior of the World) Deidamia Moran dances with costumed performers taking part in the festivities at the Shuster Center in Milan. Copyright © Donna De Cesare, 2018

Donna De Cesare is an award-winning photographer and writer on the faculty of the University of Texas at Austin where she teaches photojournalism. Her book Unsettled / Desasosiego (2013) explores the spread of U.S. gangs in Central America. She continues to focus on migration stories.

Related Articles

Video Interview with Flavia Piovesan

Flavia Piovesan is a member of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, Professor of Law at the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo and 2018 Lemann Visiting Scholar at the…

Aging: Editor’s Letter

There is no smell of pungent printers ink permeating my office. My interns—Sylvie, Isaac and Marc—are not scrambling to find FedEx boxes to send out ReVista issues to authors and photographers all over the world. I cannot feel the silken touch of the printed page…

A Story of Agricultural Change

Francisca Hernández García, 92, lives in San Miguel del Valle, a town of around 3,000 inhabitants in the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, an hour east of the capital city. She is one of the few remaining…