Alvarado, Arbenz, Arévalo

The Repair of Guatemala

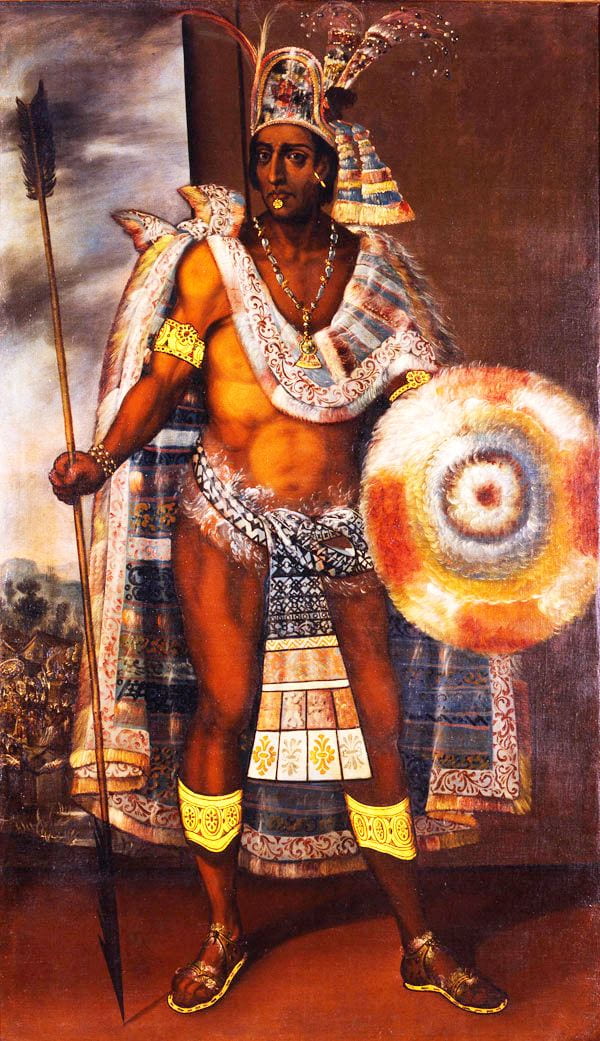

Almost exactly 500 years ago Hernán Cortés dispatched his brother-in-arms Pedro de Alvarado from newly subdued Tenochtitlán to conquer Guatemala. Violent and monumentally willful, Alvarado was a key lieutenant in the Spanish Crown’s conquest of Cuba in 1511 and Cortés’ deputy in defeating Moctezuma’s empire in 1521.

Moctezuma Xocoyotzin was the ninth Aztec emperor. He was leader of the Mexica Empire during their first encounter with Europeans and was killed by Hernán Cortés and his cohorts in 1520. The Aztec Empire collapsed to Spanish and rival Mexican Indigenous forces soon after his death. Credit: Oil on canvas painting of Moctezuma attributed to Antonio Rodríguez (1636-1691).

By 1523, Alvarado’s bravery and capacity for mass violence was renowned in Europe and the New World. Commensurate with this reputation, Cortés—now governor of New Spain—sent him to Guatemala after word reached the Spanish of a densely populated, rich territory with commercial ties to the Mexicas, but that was beyond the full control of Moctezuma’s former kingdom.

His unfettered ambition was an asset during the opening years of the conquest but Alvarado’s brutal campaign among the Maya was a disaster, inflaming their resistance. Even by the standards of the Spanish Conquest, Alvarado’s conquest of Guatemala was characterized by chaos, atrocity, and corruption. His Central American incursion destroyed his relationship with Cortés and damaged his reputation on both sides of the Atlantic. His ravaging of the Maya reverberates in Guatemalan society today.

By 1526 Cortés complained directly to Spanish King Charles V, writing that had he led the Guatemala campaign, the Maya would long have been pacified:

Official portrait of Juan José Arévalo who served as president of Guatemala from 1945 to 1951. He won the presidency with more than 85% of the vote in what is still the largest margin of victory in Guatemalan history. He is the father of current president Bernardo Arévalo. Photo credit: Government of Guatemala

Although Pedro de Alvarado makes constant war against [the Maya] …he has been unable to subject them to Your Majesty’s service; rather each day they grow stronger through the people that come to join them. I believe, however, that if I were to go that way I might, if God so willed it, win them over by kindness or some other means, for some of the provinces rebelled because of the bad treatment they received in my absence.

Pedro de Alvarado, was known for both his military brilliance and wonton cruelty. He is credited with conquering much of Central America for the Spanish Crown. Credit: Tomás Povedano (1906) paints Pedro de Alvarado. Oil on canvas

Historians compare Alvarado to a prototype Nazi and assert that his Guatemalan campaign is, “{L}odged forever in Maya memory and…cast a long and oppressive shadow over the lands and peoples that Cortés had sent him to conquer.”

The Mexican Invasion of Guatemala

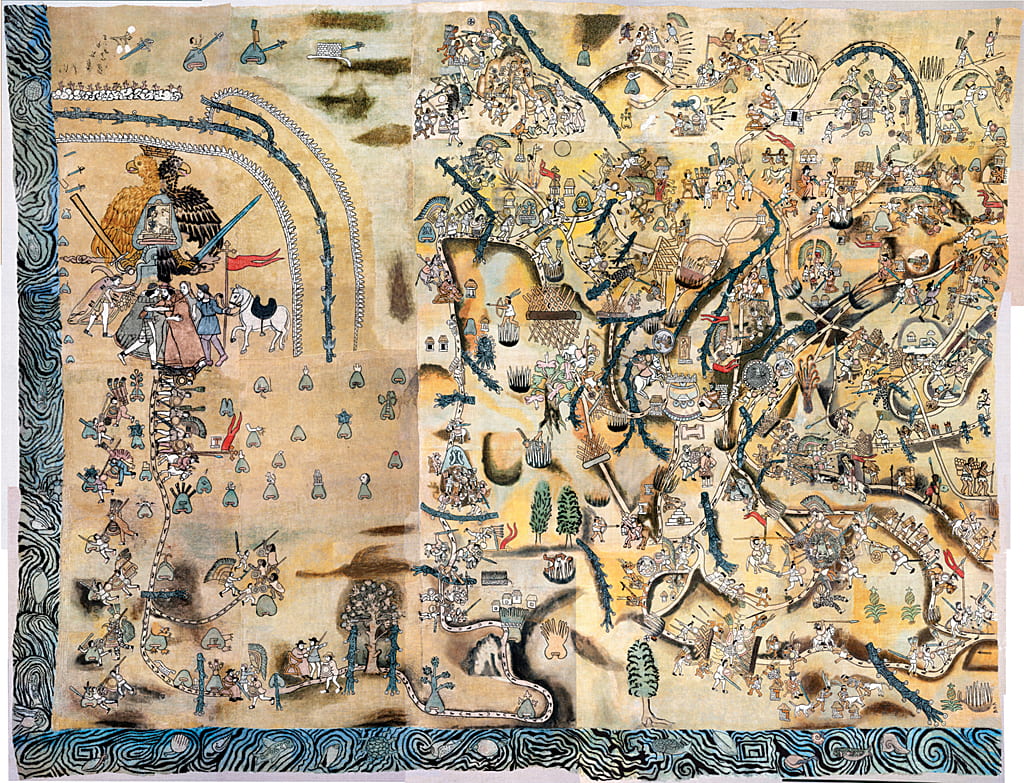

Spanish technology and fervor could take the conquest only so far. Its success depended on tens of thousands of allied indigenous warriors and their political leadership. The most careful research on the Spanish invasion of Guatemala reveals a “joint conquest” – at least from the perspective of the Spaniard’s indigenous allies – which included indigenous Mexican participation, pride, and even leadership in advancing colonial conquest and settlement. The Spaniard’s indigenous allies viewed their participation as an extension of pre-Columbian rivalries and conflicts.

Cortés’ exploited these rivalries in Mexico and Alvarado and his brothers also embraced this approach: their invasion of Guatemala consisted of perhaps a few hundred Spaniards and at least 7,000 indigenous warriors from central and southern Mexico. The Spanish invasion of Central America was more Mexican that it was Castilian and it extended a centuries-long tradition of Aztec imperialism and settlement that existed centuries before Columbus landed in the Caribbean. Without the enthusiastic support of central and southern Mexican indigenous groups, the Spanish invasion of Mesoamerica would not have been possible.

In February 1524, Alvarado’s multicultural expeditionary force assaulted the Guatemalan highlands confronting 3,000-4,000 K’iche’ warriors in a series of encounters called the Battle of Pachah, near the present-day Guatemalan highland city of Quetzaltenango.

The Lienzo de Quauhquechollan is a pictorial document created around 1530 by Nauhat scribes. It honors the victories of the central Mexican Quauhquechollan indigenous group that accompanied and contributed to Pedro Alvorado’s conquest of Guatemala in the 1520s. Credit: Universidad Francisco Marroquín.

It was a turning point —Alvarado and his Tlaxcalan and Quauhquecholtecan allies routed the K’iche’. After the battle, he tortured and then burnt Ki’che’ rulers at the stake “to strike fear in the land”—a hallmark of his campaign. Following these terror tactics, his name circulated among them the way it had earlier in Mexico—with fear and hatred.

The Guatemalan conquest dragged-on for more than a decade, punctuated by periodic insurrections due to Alvarado and his brother’s brutality. Alvarado’s brothers – and particularly Jorge Alvarado who, as lieutenant governor, consummated the conquest – assumed control over the pacification of Guatemala while Pedro’s ambition drove him on expeditions from Mexico to Peru. Pedro died in Guadalajara, Mexico in 1541 trying to subdue an indigenous revolt. Before his death he was assembling an armada to invade China.

The Battle of Pachah was the beginning of the end of Maya rule. In addition to the Spanish, central Mexican indigenous veterans colonized what is now Antigua Guatemala where, for a time, they enjoyed the privileges of and expressed pridein being victorious conquistadors. Insurrections against the Spanish and their central Mexican indigenous allies continued for centuries, but Alvarado’s campaign prevailed, and its consequences seeped into Guatemalan society during the colonial era and beyond.

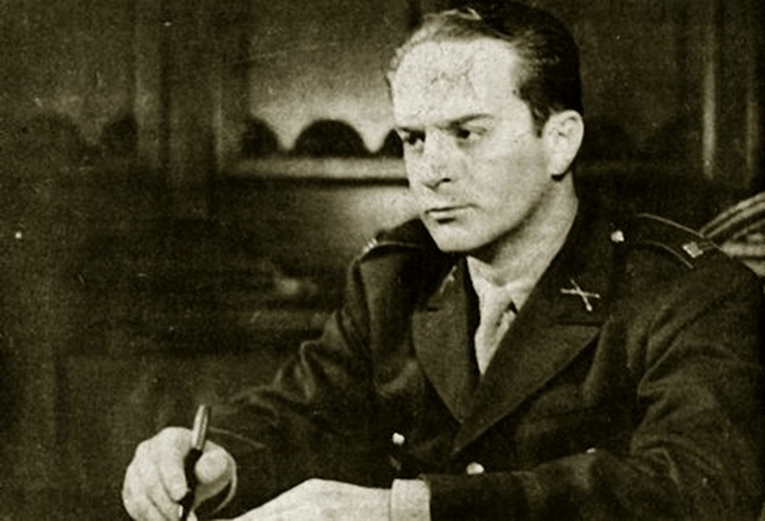

Jacobo Arbenz, 1953

In 1953, 430 years after the Battle of Pachah, a son of Quetzaltenango, located near the Pachah battlefield, rose to confront the socioeconomic and political legacy that Alvarado inflicted.

Like Alvarado, Jacobo Arbenz was a warrior of largely European extraction. Born in 1913, Arbenz’ father was a Swiss-German immigrant who settled in Quetzaltenango in 1901 and his mother was a light-skinned, middle-class Ladino woman.

Jacobo Arbenz succeeded Juan Jose Arévalo as president in 1951. He sought to deepen the Guatemalan Revolution and he led a large-scale land reform and expropriation law was passed by the Guatemalan Congress, Arbenz was removed from power during a CIA-backed coup coup d’état. in 1954. Photo credit: Prensa Libre

Described as intelligent and “magnetic” by his contemporaries, Arbenz entered the Guatemalan military academy – La Escuela Politécnica – reluctantly in 1932 after his family was struck with financial disaster. He took the entrance exam and earned a full scholarship.

Arbenz was “an exceptional student” and described as a highly capable young man who commanded respect at the Politécnica among both peers and instructors. He rose through the ranks, and, in the vein of many up-and-coming Guatemalan military men, entered politics.

But Arbenz was not another typical Guatemalan caudillo. He was reserved, introspective, and perhaps most importantly, enthralled by the world of ideas. He and his high-born Salvadoran wife, Maria Cristina Vilanova—whom he married in 1939 at age 26—were also sensitive social observers, particularly regarding the poverty and inequality endemic to Central America.

The Manifesto

In 1943 he was promoted to captain and commanded the entire corps of cadets at the Politécnica where he also taught. From the mid-1940s Arbenz’ nationalism grew and he gradually became a critic—although privately—of the role of the United States in Guatemala. By the late 1940s, both through his intellectual explorations and friendships with leftists, Arbenz became radicalized and an ardent communist in all but name, according to foreign policy expert Piero Gleijeses and others.

At first, his radicalization occurred along the same lines as millions of university students over the past 150 years: by reading Karl Marx. His wife introduced him to the Communist Manifesto. “Marxist theory offered Jacobo explanations that weren’t available in other theories,” his wife said. “Marx is not perfect, but he comes closest to explaining the history of Guatemala.”

Externally, Guatemala’s politics also drove Arbenz’ drive leftward and he began to engage the country’s volatile political culture. In July 1944, Guatemalan President Jorge Ubico was forced to resign and flee the country after a 13-year reign. Ubico was a close U.S. ally and one of Latin America’s most brutal dictators. After Ubico fell, Arbenz and allied officers intervened forcefully in the interregnum to ensure that free and fair presidential elections were held.

Arévalo the First

In December 1944—in its freest presidential election ever—a professor, Juan José Arévalo, won with more than 85% of the vote. In part for his intervention on behalf of Arévalo, the president-elect appointed Arbenz minister of defense in 1945. Arévalo’s election in 1944 launched the Guatemalan Revolution in which Arbenz was now fully engaged. Arévalo is the father of current Guatemalan President Bernardo Arévalo inaugurated in January.

“Spiritual socialism” was Arévalo’s calling card. No one knew what it meant—and this was key to its success. While his vision was (purposely) ambiguous, Arévalo unquestionably ushered in an era of unprecedented freedom and social reform.

But Arévalo was no radical—the Communist Party remained outlawed—and in the countryside, where the vast majority of the population lived, Ladinos continued to lord over the Maya centuries after Alvarado’s conquest. As late as 1945, 2% of the population controlled 72% of the arable land. In 1950, nine out of ten indigenous children did not attend school.

As the Cold War hardened in the late 1940s, even Arévalo’s moderate reforms sparked alarm in the Truman Administration. U.S. companies based in Guatemala and Guatemala’s hypervigilant ruling class fed U.S. fears that Arévalo was opening the door to the Soviet influence in America’s backyard.

Meanwhile, Arbenz’ admiration for the Soviet Union increased. Communism had transformed Russia— an impoverished and chaotic country— into an industrial powerhouse over a few decades. Particularly relevant to Arbenz as a solider was the Red Army’s defeat of the Wehrmacht, demonstrating the power of a state resting on the strength of the working class.

Decree 900

In February 1950 Arbenz resigned as minister of defense and announced his candidacy for president. The Revolution was still immensely popular and Arbenz, as its designated inheritor, won easily with 64% of the vote. He was inaugurated as the 25th president of Guatemalan in March 1951.

By the time he became president, Arbenz was a dedicated—although mostly closeted—communist. His closest advisers were communists, and his policy priorities reflected their agenda, particularly agrarian reform. Arbenz’ was convinced that agrarian reform was the key to unlocking Guatemala’s development potential and dragging its semi-feudal society into the 20th century.

Within a year—working secretly—Arbenz developed an agrarian reform law. In May 1952 it was introduced into Congress, igniting panic among landowners. But Arbenz was determined. In spite fierce opposition, the reform had become, “almost an obsession” for Arbenz. In June 1952 Decree 900—by far the most radical land reform policy in the country’s history—which sought to undo the system with roots in the encomiendas granted to the conquistadors—was passed by Congress and signed into law by Arbenz.

When he was elected many hoped the Revolution had reached its apogee and that Arbenz would steward it through another six years of moderate reform. But Decree 900 radicalized the Guatemalan Revolution, and ultimately overextended it. “Jacobo was convinced that the triumph of communism in the world was inevitable and desirable,” his wife said. “The march of history was toward communism. Capitalism was doomed.” Within a year the world’s leading capitalist power would expel Arbenz from power, shattering his family and the Revolution.

On the merits, Decree 900—despite excesses—was a success. Before Arbenz was overthrown in 1954, one-quarter of all arable land in Guatemala was expropriated benefitting perhaps 138,000 families. Rural wages increased. Decree 900 clearly improved the economic well-being of large swaths of the Guatemalan countryside. At the same time, the Truman Administration saw this program as an escalation of communist influence in Guatemala.

Golpe de Estado

Tensions escalated when Dwight Eisenhower became president in 1953. Although perhaps best remembered for his end-of-term “military-industrial complex” speech, Eisenhower was nevertheless an avid purveyor of covert action to overthrow democratically elected, left-leaning governments deemed hostile to US interests. He didn’t waste time putting the young CIA to use. Mohammad Mosaddegh in Iran came first in August 1953. Arbenz was next.

As calls for regime change increased, Arbenz and his hard-left advisors miscalculated, worsening their position. In 1953 plans to overthrow Arbenz were well underway at the CIA and may have been irreversible. But Arbenz, despite his retiring demeanor, was stubborn—and naïve—providing public ammunition for U.S. claims that Guatemala was becoming a Soviet client state.

In one example, when Joseph Stalin died in March 1953, the Guatemalan Congress – with Arbenz’ support—honored him with a moment of silence. At the time, Stalin was seen by the left as a global champion of the working class and anti-fascist resistance. Nevertheless, this was the height of the McCarthy era and Guatemala was the only country in the Western Hemisphere to honor him. The McCarthy Era—the repression against left-leaning citizens named for Wisconsin Sen. Joseph McCarthy—peaked during the early-1950s as the senator and his supporters warned of widespread communist infiltration of American government and society. He accused the Truman Administration of being soft on communism to the point of treason and even clashed with the more hardline anti-communist Eisenhower before he was censured by the senate in 1954 and finished out his term in disgrace.

A series of additional events escalated tensions to the breaking point and by June 1954, Arbenz was gone. The details of the CIA-organized coup are masterfully documented in Piero Gleijeses’ meticulous account Shattered Hope. 2024 is the 70th anniversary of Operation PBSuccess, as the CIA named the operation, and its repercussions are still felt throughout the Western Hemisphere. In coming years, leftist insurgencies ignited from Mexico to Argentina with the right-wing backlash killing hundreds of thousands, most of them young people.

In Guatemala—whatever one thought of Arbenz—the 1954 coup sparked a series of societal traumas. After the coup Guatemala spiraled into mass arrests, impunity and torture. Opponents of the U.S.-installed regime “disappeared,” auguring a tactic that would spread throughout the hemisphere in coming decades.

One close observer of the coup as it unfolded in Guatemala City, was a 25-year-old, upper-middle-class Argentine doctor named Ernesto Guevara. Che arrived in Guatemala in December 1953 an already radicalized young man attracted by the Arbenz’ increasingly leftist orientation and ended up sheltering in the Argentine Embassy during the coup.

Seeing point-blank the red fangs of American Cold War imperialism ignited Guevara’s transformation into an apostle of revolutionary violence. Just several years later, in 1956, he helmed a revolutionary expedition with bravery and tactical brilliance in Cuba and then with almost suicidal recklessness and incompetence in Bolivia where he was captured and executed with CIA consent in 1967.

The coup was disastrous for Guatemala leading to the 36-year Guatemalan Civil war that ended in 1996, claiming200,000 lives including many hundreds of massacres of Maya communities. Guatemala remains a society riven with corruption and some of the most severe inequality in the world.

Arévalo, 2023

In 2023, 500 years after Alvarado’s assault on Guatemala and 70 after Arbenz unsuccessfully challenged the legacy of the Spanish and Nahuat invasion, a new hope arose from an old political lineage.

Bernardo Arévalo’s similarities with his reformist father are uncanny. Like Juan José, Bernardo is a moderate-left academic who lived many years abroad. Bernardo was born in Uruguay where his father fled for a time after the 1954 coup.

And both can boast of impressive presential electoral victories—85% for Juan José in 1944 and 61% for Bernardo in 2023. But the similarity of their presidential tenures ends there. With his massive victory Juan José took office without interference—thanks in great part to Arbenz—and enjoyed a largely successful six years as president.

Bernardo Arévalo at his inauguration on January 15, 2024, as the 52nd president of Guatemala in 2024. He is the son of former Juan José Arévalo and was a long-shot candidate who emphasized uprooting the deeply embedded institutional corruption that plagues Guatemala. Photo credit: Presidencia Colombia (Juan Diego Cano).

For his part, after his victory in August 2023, Bernardo Arévalo faced obstruction from an entrenched coterie of elites intent on maintaining their privileges. But 2023 is not 1953 and “the pact of the corrupt” that sought to prevent Arévalofrom taking office failed. Arévalo was inaugurated as the 52nd president of Guatemala on January 15.

As in 1954, the stance of the U.S. government was decisive— and its refusal this time to back Guatemalan reactionaries—was instrumental in safeguarding democracy 70 years after it oversaw the dismantling of the Guatemalan Revolution. In November, the Biden Administration imposed visa restrictions against government officials seeking to block the peaceful transition of power to Arévalo – many of them in Guatemala’s Public Ministry, the equivalent of the Department of Justice.

Even as President Arévalo will need that support to confront a society riven by the consequences of Alvarado’s invasion and Arbenz’ aborted Guatemalan Revolution. Guatemala still suffers from extreme inequality, profound institutional corruption, and half of its citizens subsisting below the poverty line. Unsurprisingly, it is the largest Central American source country for unauthorized migration to the United States. While Guatemala is the largest economy in Central America is has among the highest malnutrition rates in the world.

Violent overthrow is less of a threat to Arévalo’s anti-corruption agenda than the danger that it gets co-opted into a political system where corruption is pervasive and simply required to get things done. In coming days—and in spite of recent victories—Guatemalans and their international supporters will need all the tools at their disposal to begin to reverse the momentum of terror that Alvarado initiated in the land of the Maya half a millennia ago.

Andrew Wainer is a researcher and writer based in Washington, DC who previously lived and worked in Mexico and Central America. His analysis is published in Development in Practice, International Migration and the Stanford Social Innovation Review. He has also written on history and current events for the Los Angeles Times, The Guardian, The Atlantic, The Hill, The Washington Post and Lawfare, among other publications. You can connect with Andrew on X @AndrewWainer.

Related Articles

Unequal Beginnings: Artificial Intelligence and Latin America’s Educational Divide

Latin America has never lacked talent. What it has lacked, historically, structurally and persistently is equal access to the conditions that allow talent to flourish.

Financial Institutions: Strengthening the Rule of Law in Latin America

Latin American countries continue to accumulate laws, regulations and rules. These legal instruments need to be implemented and then enforced.

Extractivism and Colonialism in Argentina: A View from the Patagonia

It was snowing the day in early August when I arrived at Lof Pillan Mahuiza, a Mapuche-Tehuelche community around 60 miles from Esquel, the provincial capital of Chubut, Argentina.