An Interview with Lita Stantic

Producer Lita Stantic (b. 1942) played a crucial role in the nuevo cine argentino that surged to international prominence in the late 1990s and early 2000s by discovering and supporting young, emergent filmmakers- Lucrecia Martel, Pablo Trapero, Israel Adrián Caetano, Pablo Reyero, among them- who would together redefine Argentina as a newly vibrant center for cutting edge art cinema. Equally renown for her eleven year partnership with Maria Luisa Bemberg, one of Argentina’s most important women directors, Stantic also proved herself as a filmmaker with her powerful and autobiographically inspired debut feature, A Wall of Silence/ Un Muro de silencio (1993), a candid exploration of the still deeply sensitive topic of the desaparecidos during the darkest years of the dictatorship. Incredibly generous with her time and opinions, Lita Stantic was kind enough to receive me on two early autumn afternoons in May, at her beautiful office in the Palermo Hollywood neighborhood of Buenos Aires where we discussed the course of her long and storied career.

“EL NUEVO CINE ARGENTINO”

Haden Guest: What does the term “New Argentine Cinema” mean to you? Every new director that has come on the scene since the 1990s is grouped together in this category, despite the group’s heterogeniety that embraces directors with very diverse talents and perspectives. But if we consider this new cinema more precisely as a historical era beginning with Martin Rejtman and with Israel Caetano’s Pizza, birra, faso (1998), can we consider that el nuevo cine argentino is still well and alive or is it something else, a type of variation?

Lita Stantic: There are now new generations and perhaps with the new generations, the same impact is not felt as with the so-called New Argentine Cinema. And moreover, in previous years, there were generations of young folk in film that were quite mixed, no? The generation— the one that began in the late 90s——is more homogeneous in regards to age, with everyone 20-ish to 30-ish. And I believe this hadn’t happened since the 60s, when a generation of people were making film in the style of the New French Wave. In regards to the generation of the 60s, this generation was more individualistic. The generation of the 60s was more of a cohesive group. This generation isn’t as supportive of each other. Here they are…I don’t know; the world changed, and directors became much more individualistic…. Because of this, many of them don’t like to be categorized as “nuevo cine argentino.” They don’t want to be considered part of a single generation. It is not a generation, because it is a group of people who began to make their first film over a number of years, but these films represent a departure in Argentine film.

HG: And certainly we can’t keep using the word “new” forever?

LS: And the new is already starting to be old, right? The ex-new. I remember once when René Clair was coming back from the Mar del Plata Film Festival in the 50s, he was asked about the new wave. And they say that, looking at the sea, he said, “All the waves are new.”

HG: Many of New Argentine Cinema’s first films have a sense of specifically Argentine settings such as Lucrecia Martel’sSalta or Bolivia, which is a portrait of a Buenos Aires neighborhood, or the suburbs in Un Oso rojo, or Mundo grúa that capture the texture of the city, or Tan de repente, that creates a sharp contrast between the city and the sea.

LS: I am the daughter of first-generation immigrants, and I believe that one sets down one’s roots more deeply, no? Ever since I was a little girl, I saw Argentina as a place of salvation. I associated Europe with the war. It seems unbelievable after all that has happened in Argentina. I could not live in another place, and during the dictatorship, I did not leave, in spite of the fact that I was connected to many people who disappeared. I thought at one point that I was going to leave, but I had a very strong relationship with the country and I decided to stay.

HG: One of the very interesting points about New Argentine Cinema is the political strand underlying it, sometimes quite subtle. One of the most well-known films is Lucrecia Martel’s La ciénaga (2001),which is for me is a good example of a work that has a certain political dimension, if we consider the very strong comparison that the movie makes about the two families from very distinct socio-political classes.

LS: I met Lucrecia Martel in 1998. The screenplay for La Ciénaga had already been written and for her the film was a more existential one. What happens is that history imposes itself. At times, an author is showing what she has lived without any intentions of pointing out a certain theme, of marking a historical moment.

HG: Most certainly. But, let’s take another example, Pablo Trapero’s Mundo grúa (1999). If we look at that film retrospectively, one notes that it captures a historical moment perfectly. In this case, the moment of Argentina’s national crisis. Wouldn’t you agree?

LS: The times I asked Pablo Trapero himself when he was making Mundo grúa, if the film had something to do with the crisis of the 90s in Argentina, he denied it. The curious thing is that there are coincidencesand at time the context filters through; the context always appears, and the context is political. He himself did not think the picture was very political, because in a certain way, Mundo Grúa is the failure of Menemism.

HG: And depicting the working class on the big screen is in and of itself a political act, isn’t it?

LS: But he did not like giving the film this connotation at the time. But it happens. Neither was La ciénaga a film about the decadence of the middle class when Lucrecia Martel conceived it.

HG: But as a producer, do you yourself—with a bit of distance between yourself and your projects—see these political aspects in your work?

LS: No. I did not read a political context in the screenplay for La ciénaga. When I read the screenplay for La ciénaga, as I’ve recounted many times, I thought it was Chekhov, and after that, I discovered it wasn’t Chekhov after all, it’s more Faulkner. isn’t it?

HG: In your career, you’ve given support to many directors and have helped a very talented new generation. But can we also understand your career in another fashion, as a way of fomenting national cinema, of helping to create a new Argentine cinema? Were you thinking of this during the first years of the New Argentine Cinema in the 1990s?

LS: I would say no. If someone of my generation had brought me a book that I liked, I would have produced it. I did not opt for a particular generation, first of all. I like films that leave something with me. That is, I like to leave the movie house as a transformed person. And well, the selection has to do a bit with this factor. I want to direct a screenplay that tranforms me, or will transform those who view it. I was shaped as a young woman by film and reading. For me, I am what I am,let’s say, and I have a certain ethic and a way of seeing life because of what I read and saw in the movies during my childhood, and a little later on, also. I think that in a certain way film tells us something about humanity. It makes us undertand more. This is what makes me select a film to direct—-also in the films I like to watch. I like the Dardenne Brothers more than I do U.S. action films. I don’t generally watch action films. But I like the films that make me keep on thinking, that can still transform me, that can make me see life in some other fashion, and understand mankind, humanity.

In general, I don’t think of how a film is going to do until I have to screen it. That’s when I begin to think about the business of film, but I do not choose the screenplay by whether I think it is going to do well comercially or not, that’s for sure. I pick something that I like, that gets to me in a certain way. I watch shorts that the director has done previously in order to decide, “Well, I’ll go ahead with this project.” But no, I don’t think about the commercial aspect of the film. I save that for later.

FROM EARLY ON

HG: What was the first time that you realized that film had the possibiity to transform, to change, to create a distinctive viewpoint, a way of understanding and seeing the world?

LS: Let’s say that I had a passion for film ever since I was very young. My idea, when I was an adolescent, around 13 or 14 years old, was that I wanted to be a film critic. Because, well, at that moment, and even when I was finishing up high school, it was highly unlikely that the future of a woman could be in the film industry. Women weren’t involved in making film.Production teams were completely masculine. So it seemed to me that the closest I could get to film was by being a film critic. But, let’s say, the closest I thought could come to the world of film would be by becoming a film critic. But I watched a lot of film in my adolescence, a whole bunch of film, and in a certain sense, much film of revision.

For me, the films that most influenced me going into my 20s were the Polish films from the 50s and the beginning of the 60s and New Italian Realism. I believe the experiences were the strongest I’d lived. I wanted to see absolutely everything that had been done in this genre. But naturally, I went through this stage and later a new one came, the stage in which one thinks that one can make the revolution through film. And so I got involved with activist film, the so-called cine de compromiso. This was at the end of the 60s.

Fundamentally, for us, La hora de los hornos was a very strong experience in 1968. At that moment we thought that film had to be political. We began to distribute La hora de los hornos clandestinely.

HG: This was the Liberation Film Group, known in Spanish as Grupo Cine Liberación?

LS: Yes. The group enlarged and others were formed in which film was shown clandestinely with a 16 milimeter projector in people’s homes.

HG: Certainly. And how were people invited to see the films? By word of mouth?

LS: Someone would invite his or her friends or study group and circles of 15 or 20 people were formed. They connected up with us and we would project La hora de los hornos followed by a discussion.

HG: And did you all organize these discussions or were they spontaneous?

LS: No, we organized these discussions at the end of the films ourselves. In 1969, we added another film about the Cordobazo that was made by a collective of ten directors. A few years ago, Fernando Peña rescued this film, whch had been completely lost.

Well, it was the period of the dictatorship, the years 69, 70. But it wasn’t like the dictatorship later on. One faced very little risk compared with what happened after 1976.

The film about the Cordobazo,whose anniversary is precisely today, depicted the students and workers movement in Cordoba that exploded on May 29, 1969, as a more politicized prolongation of the movement events in France in 1969. To take to the streets, well, it was to think you could change the world. In all of Latin America, this happened in the most political way. The Cordobazo was a very fundamental, significant, date. Workers, students, everyone took to the street, it was a complete mess. In all of the television channels, there were images of the Cordobazo. These images showed the mounted police retreated in the face of rock-throwing students. This was quite a crucial moment. Many young people thought it was possible to make the revolution. These were beautiful times because it’s marvelous to think that one can change the world.

HG: What was your role in the Grupo Cine Liberación? Were you one of the organizers?

LS: No, no. I participated in Grupo Cine Liberación only by helping to circulate the films. I helped Pablo Szir, who was my partner at the time and is the father of my daughter, to make a film that he directed. It had its own screenplay on which I and Guillermo Schelske collaborated. The film was about some Robin Hood-type bandits that the police and Army had killed in 1967; it was a fairly recent situation. The film was called Los Velázquez, and it has entirely disappeared. Pablo today is also among the disappeared. We also spent two years filming the movie about a peasant who denounces police arrogance; he gets together with the Robin Hood-style bandits and together they are supported by the peasantry in the Chaco region because with the money they make from robberies and kidnappings, they help the peasants. Today Isidro Velásquez is a myth in the Chaco region, where he lived and died.

This is all very strange because the story was investigated and published by sociologist Roberto Carri (Albertina’s father) in book form Isidro Velázquez: formas prerrevolucionarias de la violencia in 1968. Pablo read Carri’s book and wanted to make a film, a mixture of documentary and fiction about the Velázquez group. A documentary about the Chaco’s economic situation which caused these folks to rebel against injustice, and subsequently to be protected to a certain extent by the peasants. Because of the peasant support, the police couldn’t get anywhere in their attempt to defeat Velásquez; they had to call in the Army to kill him. Much has been written about the Velázquez group and nowadays Isidro Velázquez is celebrated as a hero in Chaco. Moreover, in the era when Perón returned, graffitti sprang up on the walls, “Perón vuelve, Velázquez vive.” (Perón returns; Velázquez lives on!) We experienced this Velázquez phenomenon as a prerevolutionary form of violence because in 1969 armed groups had already begun to spring up.

UN MURO DE SILENCIO

HG: Let’s talk about Un muro de silencio (1992), your only long feature film and a highly personal one. Can you tell me something about the origins of this project and your objectives and wishes as its director?

LS: Well, I began with the idea of Un muro de silencio long before I actually directed it. In 1986, I made Miss Mary together with María Luisa Bamberger, with Julie Christie as the female lead. It was Julie Christie who stimulated me about the idea of telling this story that has much to do with my personal experience. Because Julie set herself up here in Argentina and began the quest to learn about out recent past.

Julie came with the intention of staying seven weeks and ended up staying many, many months. She fell in love with Argentina and this was the origin of the idea of the English woman who comes to the country to understand what happened here. After this experience with Julie, I decided to write a screenplay, which I ended up doing in collaboration with Graciela Maglie and Gabriela Massuh.

What I wanted was to talk about memory,about a person who wanted to forget. But memory always returns. And it returns in the most hellish way, with hallucinations. The character believes she has seen her disappeared husband in the street. At times one wants to forget ab out the traumatic experiences one has had in life, and wants to say, “Well, my life is beginning right now,” and it’s not that way. For me, the basic and indeed the only way of keeping one’s sanity is to preserve memory.

What makes me proud about this film is that I feel that many peope who work on human rights identify with this film. History is recounted from within, no? Because all of a sudden one begins to talk about something that one has never voiced before——that many of the disappeared were kept alive for a while. One didn’t talk about this much during the time of the dictatorship. It’s almost as if to have been kept alive could signify something incorrect. But afterwards, things were whitewashed even more.

HG: It certainly does complicate the story. Completely. The history that was already known throughout the world up until now. No just in Argentina. But also, through taking an individual perspective, a personal persepctive, is one of the most effective and powerful ways to talk about a very complicated and extensive situation. It’s a way of looking at history not as a sweeping epic, a huge melodrama, without taking into acocunt the way it is seen from the intimate two eyes of a person. I think this has even more power. And I believe this is the importance of this project.

LS: In a way, this film is about secrecy, about hiding. It is not only about the need to forget and the impossibility of forgetting, but also about secrecy, because there is secrecy in regards to the daughter. And well, they are personal things. Very painful things, and I believe that it is because of this that so many people who have lived this type of experience identify with the film.

HG: But it also seems to me that the film demonstrates an attitude about how to talk about political themes through film, and to have, as it has been said, a transformative experience. But it seems to me it is also a way to tallk about the political through film and, as has been said, to have a transformative experience. And no to hace an attitude of didacticism in film. Because I believe that’s the problem with political film.

LS: I believe that this is a film in which the process begins when the film ends. And in this sense, yes, this is a thinker’s film.

Una entrevista con Lita Stantic

Por Haden Guest

Producer Lita Stantic (b. 1942) played a crucial role in the nuevo cine argentino that surged to international prominence in the late 1990s and early 2000s by discovering and supporting young, emergent filmmakers- Lucrecia Martel, Pablo Trapero, Israel Adrián Caetano, Pablo Reyero, among them- who would together redefine Argentina as a newly vibrant center for cutting edge art cinema. Equally renown for her eleven year partnership with Maria Luisa Bemberg, one of Argentina’s most important women directors, Stantic also proved herself as a filmmaker with her powerful and autobiographically inspired debut feature, A Wall of Silence/ Un Muro de silencio (1993), a candid exploration of the still deeply sensitive topic of the desaparecidos during the darkest years of the dictatorship. Incredibly generous with her time and opinions, Lita Stantic was kind enough to receive me on two early autumn afternoons in May, at her beautiful office in the Palermo Hollywood neighborhood of Buenos Aires where we discussed the course of her long and storied career.

EL NUEVO CINE ARGENTINO

Haden Guest: ¿Que significa para Ud. el término “el nuevo cine Argentino”? A pesar de la heterogeneidad del grupo clasificado como miembros del nuevo cine—un grupo que incluye directores de talento y perspectiva muy diverso—se clasifica en este grupo todos los nuevos directores argentinos que han aparecido desde los 1990s. Pero si consideramos el nuevo cine más precisamente como una etapa histórica, que empezó con Martin Rejtman y con Pizza, birra, faso (1998) de Israel Caetano, ¿podemos decir que todavía está activo el nuevo cine argentino, o es lo de hoy otra cosa, un tipo de variación?

Lita Stantic: Ahora hay nuevas generaciones y quizás no se siente tanto el cambio, el impacto que se dio con el llamado nuevo cine argentino. En los años anteriores Los directores pertenecían a varias generaciones. Esta generación que fue la que apareció en la segunda parte de la década del 90 fue más homogénea con respecto a la edad, porque tenían entre veinte y pico y treinta y pico de años. Y creo que eso no se daba desde los años 60, en que hubo una generación de directores que hacía un cine estilo Nueva Ola del cine francés. Creo que en relación a la generación de 60, esta generación es más individualista. En esa generación, se apoyaban más unos a otros. No sé, el mundo cambió, y también los directores se volvieron más individualistas. Por eso, a muchos de ellos no les gusta que se los incluya en el llamado “nuevo cine argentino¨. Es un grupo de gente que empieza a hacer su primera película a lo largo de una cantidad de años y esas películas son como un quiebre dentro del cine argentino.

HG: Y claro que no podemos seguir usando la palabra “nuevo” para siempre, ¿verdad?

LS: Ya lo nuevo empieza a ser viejo, ¿no? Lo ex-nuevo. Recuerdo que vino una vez al festival de Mar del Plata en los años 60 René Clair, y le preguntaron por la nueva ola. Dicen que, mirando al mar, dijo, “Todas las olas son nuevas”.

HG: Algo que tiene muchas de las primeras películas del nuevo cine es un sentido de lugares específicamente argentinos, como la Salta de Martel, o Bolivia, que es un retrato de un vecindario porteño, o el suburbio de Un Oso rojo, o Mundo grúa que captura la textura de la ciudad, o Tan de repente, que hace muy fuerte el contraste del mar y ciudad.

LS: Yo soy hija de inmigrantes de primera generación, y creo que uno se enraíza más, ¿no? De chiquita, vi Argentina como el lugar de la salvación. Relacionaba a Europa con la guerra. Parece mentira, pero, después pasó de todo en el país. No podría vivir en otro lugar, y en la época de la dictadura no me fui, a pesar de que estaba relacionada con mucha gente que desapareció. Pensé en un momento que me iba a ir, pero tengo una relación muy fuerte con este país y decidí quedarme.

HG: Uno de los puntos muy interesantes del nuevo cine argentino es el hilo político, a veces muy sutil, que pasa por muchas de las películas. Una de las películas más conocida que se produjo, La ciénaga (2001) de Lucrecia Martel, es para mi un buen ejemplo de una obra que tiene una cierta dimensión política- si consideramos la comparación muy fuerte que hace la película de las dos familias que representan distintos lados socio-económicos.

LS: Yo conocí a Lucrecia Martel en el año 98. El guión de La Ciénaga ya estaba escrito y para ella era una película más existencial. Lo que pasa es que se le impuso la historia. A veces el autor está mostrando algo que ha vivido, y se le imponen contextos, se le impone la historia, sin que haya la intencionalidad de marcar algo, de marcar un momento histórico.

HG: Claro. Pero, tomamos otro ejemplo, otra película que produjo, Mundo grúa (1999) de Pablo Trapero. Si uno mira retrospectivamente hacía una película como Mundo grúa (1999) se nota como captura perfectamente un momento histórico, ¿no? En este caso, el momento de crisis nacional para Argentina.

LS: Las veces que le han preguntado a Pablo Trapero en la época de Mundo grúa, si la película tenía algo que ver con la decadencia de los 90 en Argentina…él lo negaba. Lo curioso de acá es que se dan coincidencias y a veces se filtra, de alguna manera aparece el contexto, y el contexto es lo político. Él no pensó en que la película era política—y es muy política, porque de alguna manera, Mundo Grúa es el fracaso del Menemismo.

HG: Y representar a la clase obrera en la gran pantalla es un acto político, ¿no?

LS: Pero a él no le gustaba que se le diera esa connotación en ese momento. Pero pasa. Tampoco La ciénaga era una película sobre la decadencia de la clase media cuando la pensó Lucrecia Martel.

<

HG: Pero usted, como productora, está a unos pasos afuera del proyecto. ¿Se fija usted en estos aspectos políticos?

LS: No. Yo no leí en el guión de La ciénaga un contexto político. Cuando leí el guión de La ciénaga, como he contado varias veces, creí que era Chejov, y después me di cuenta que no era Chejov, que más bien es Faulkner, ¿no?

HG: En su larga carrera ha apoyado a bastantes directores y ha ayudado una generación nueva muy talentosa. ¿Pero también podríamos entender su carrera en otra manera, como un intento de apoyar un cine nacional, de ayudar a crear un cine nacional? ¿Estaba pensando en esto durante los primeros años del nuevo cine argentino en los noventas?

LS: Yo diría que no. Si se hubiera presentado alguien de mi generación en estos años con un libro que a mí me gustara, lo habría producido. No es que elegí una generación, primero. Y Me gustan las películas que, de alguna manera, me dejan algo, Digamos, me gusta salir del cine transformada. Y bueno, la elección se debe un poco a eso. Quiero producir un guión que me transforme, o transforme a la gente. Yo me formé en el cine y la lectura. Para mí, soy como soy, digamos, y creo que tengo una ética y una manera de ver la vida por lo que pude leer y ver en cine en mi infancia, mi adolescencia, y un poco más tarde también Pienso que de alguna manera el cine tiene que contar algo sobre la humanidad. Hacernos comprender algo más. Esa es la idea en la elección—también en el cine que me gusta. Me gustan más los Hermanos Dardenne que las películas de acción americanas. Por lo general no veo películas de acción. Pero bueno, me gusta el cine que, de alguna manera me deja algo, que todavía me pueda transformar, que me puede hacer ver la vida de otra forma, y entender más a los hombres, a la humanidad.

En general, yo no tengo la expectativa del negocio hasta que tengo que estrenar. Ahí empiezo a pensar en el negocio, pero no elijo un guión pensando en la comercialidad del producto, eso es seguro. Elijo algo que a mí me guste, que me llegue de alguna manera, Veo un corto anterior, que haya hecho el director, como para decidir: “Bueno, sí, me lanzo con este proyecto”. Pero no, no pienso en lo comercial que puede ser la película. Después, naturalmente sí, cuando estoy por estrenar.

DESDE TEMPRANO

HG: ¿Cuándo fue la primera vez que se dio cuenta de que el cine tenía esa posibilidad de transformar, de cambiar o inventar un distinto punto de vista, una manera de ver y entender el mundo?

LS: Digamos, yo tengo pasión por el cine desde muy pequeña. Mi idea, cuando era adolescente o antes, cuando era púber, digamos, a los 13, 14 años era ser crítica del cine. Porque bueno, en ese momento, y aún cuando terminé la escuela secundaria, era muy poco probable el futuro de una mujer en el cine. No había equipos con mujeres. Los equipos eran totalmente masculinos. Entonces me parecía que el acceso a estar cerca del cine era la crítica de cine. Pero, digamos, vi mucho cine en la adolescencia, muchísimo cine, y de una manera mucho cine de revisión.

Para mí, las películas que me marcaron alrededor de los 20 años, fueron las polacas de fines de los 50 y principios de los 60 y el Nuevo Realismo Italiano. Creo que fueron las experiencias más fuertes que viví. Quería ver todo lo que se había hecho al respecto de ese cine, Pero, naturalmente pasé por esa etapa y después vino otra, la etapa en que uno pensaba que a través del cine se podía hacer la revolución. Y entonces me encuadré en el cine de compromiso, eso fue ya a fines de los 60.

Fundamentalmente para nosotros fue una experiencia muy fuerte La hora de los hornos en el año 68. Y en ese momento pensamos que el cine tenía que ser político. Comenzamos a difundir La hora de los hornos clandestinamente.

HG: ¿Eso fue el Grupo Cine Liberación?

LS: Sí. El Grupo Cine Liberación se amplió, y se formaron grupos que, con un proyector de 16 mm., proyectaban películas clandestinamente en casas.

HG: Claro. ¿Y cómo invitaron a la gente para ver las películas? ¿Fue algo del boca a boca?

LS: Alguien invitaba a sus amigos o a un grupo de estudio y se armaban grupos de 15 ó 20 personas. Se conectaban con nosotros y proyectábamos La hora de los hornos con un debate posterior.

HG: Y estos debates, ¿los organizaron ustedes, o fue algo más espontáneo?

LS: No, nosotros mismos lo organizábamos con debate al final de la proyección. Y en el año 69 se agregó otra película sobre el Cordobazo que realizaron diez directores. Hace pocos años Fernando Peña rescató esa película, que estaba perdida.

Bueno, era época de dictadura, el año 69, 70. Pero no era una dictadura como la que vino después. El peligro que se corría era muy pequeño en relación a lo que pasó después del 76.

A la llegada de La hora de los hornos se sumó un año más tarde el Cordobazo, un hecho que se festeja justamente hoy, que fue un movimiento de estudiantes y trabajadores en Córdoba que estalló el 29 de mayo de 1969, como una prolongación más politizada del 68 francés. Salir a la calle, pensar que, bueno, que se podía cambiar al mundo. En toda Latinoamérica se dio de una manera más política.

El Cordobazo fue una fecha fundamental. Salieron a la calle obreros, estudiantes, hubo un desmadre. En todos los canales de televisión, había imágenes del Cordobazo. En esas imágenes la policía montada retrocedía frente a las pedradas de los estudiantes. Fue un momento bastante crucial. Mucha gente joven pensó que era posible hacer la revolución. Fueron épocas muy bellas, porque pensar que se puede cambiar el mundo es maravilloso.

HG: ¿Cuál era su papel en el Grupo Cine Liberación, ¿estaba una de las organizadoras, o…?

LS: No, no. Yo estuve en el Grupo Cine Liberación solamente en el tema de difusión de las películas, y con Pablo Szir –que es el padre de mi hija, que en esa época era mi pareja –hicimos una película que él dirigió, con libro propio y con colaboración mía y de Guillermo Schelske sobre unos bandidos tipo Robin Hood que la policía y el ejército habían matado, en el año 67—era bastante reciente la situación. La película se llamó Los Velázquez, y ha desaparecido. Pablo es hoy también un desaparecido. Estuvimos dos años filmando una película, sobre un campesino que se revela de la prepotencia policial , se une a otro, y es apoyado por los campesinos en el Chaco porque con las ganancias de sus robos y sus secuestros ayuda a los campesinos. Hoy Isidro Velásquez es un mito en el Chaco, que fue la provincia donde vivió y murió.

Es muy extraño todo esto porque esta historia fue investigada y publicada por un sociólogo Roberto Carri (el padre de Albertina) que en 1968 publicó el libro: Isidro Velázquez: formas prerrevolucionarias de la violencia. Pablo leyó el libro de Carri y quiso filmar una película, una mezcla de documental y ficción sobre los Velázquez. Un documental sobre la situación económica del Chaco, y esta gente que se revela frente a injusticias y que después termina de alguna manera protegido por los campesinos. A tal punto la policía no puede con él, que tiene que recurrir al ejército para poder matarlo. Hay escritos sobre los Velázquez y hoy en día en el Chaco, se festeja a Isidro Velázquez como un héroe,. Más aún, en la época del regreso de Perón, escribían en las paredes, “Perón vuelve, Velázquez vive”. Lo vivimos como una forma prerrevolucionaria de la violencia, , porque ya en 1969 empiezan a surgir los grupos armados.

UN MURO DE SILENCIO

HG: Hablamos de Un muro de silencio (1992), el único largometraje que ha dirigido y un proyecto muy personal. ¿Me puede contar algo sobre los orígenes de este proyecto, y sobre sus intenciones y deseos como directora?

LS: Bueno, yo empecé con la idea de Un muro de silencio mucho antes del año en que la dirigí. En el año 86, hicimos con María Luisa Miss Mary, con Julie Christie como protagonista. La que me provocó un poco la idea de contar esta historia, que tiene que ver bastante con una experiencia personal, fue Julie Christie. Porque Julie se instaló acá y empezó a querer informarse sobre nuestro pasado reciente.

Julie vino por siete semanas y se quedó un montón de meses. Se enamoró de Argentina, y es un poco la idea de la inglesa que viene a Argentina para entender algo de lo que pasa acá. Después de esa experiencia con Julie quise escribir un guión que terminé haciendo con Graciela Maglie y Gabriela Massuh.

Yo quería era hablar de la memoria, de una persona que quiere olvidar. Pero la memoria siempre vuelve. Y vuelve de la manera más infernal, con alucinaciones. El personaje cree ver a su marido desaparecido en la calle. Por momentos uno quiere olvidar las experiencias traumáticas que le pasaron en la vida, y quiere decir, “Bueno, mi vida empieza ahora”, y, no. Para mí lo fundamental y la única manera de tener sanidad mental es conservar la memoria.

Lo que me enorgullece de la película es que siento que mucha gente de derechos humanos se sintió identificada. Estaba contada la historia desde adentro, ¿no? Porque de repente se hablaba de algo de lo que no se había hablado — que a muchos desaparecidos, los mantuvieron vivos un tiempo. Y de esto no se hablaba mucho en la época de la dictadura. Era como que haber permanecido vivo podía significar algo incorrecto. Pero después las cosas se blanquearon más.

HG: No, complica la historia. Completamente. La historia que ya estaba conocida en el mundo, entonces. No solamente en Argentina. Pero también, para mi es tomar una perspectiva individual, personal para hablar de una situación muy complicada, muy grande, es una de las maneras más efectivas, más poderosas, ¿no? De no tratar de decir una historia así como una épica, algo así como una gran historia, un gran melodrama, sino tomarlo desde los dos ojos de una persona, así. Yo creo que tiene más, no sé, más poder. Y yo creo que esa es la importancia de este proyecto. Y, bueno, y…

LS: De alguna forma la película trata del ocultamiento. No sólo de la necesidad de olvidar y la imposibilidad de olvidar, sino del ocultamiento porque hay un ocultamiento con respecto a la hija. Y bueno, son cosas personales. Muy dolorosas, creo que por eso también mucha gente que ha vivido este tipo de experiencia se identifica con la película.

HG: Pero también me parece que es una actitud sobre cómo hablar de temas políticos con el cine, y tener, como ha dicho, una experiencia transformativa. Y no tener una actitud de un tipo didacticismo en el cine. Porque yo creo que ese es el problema con el cine político, que es…

LS: Yo creo que es una película en que el proceso empieza cuando la película termina. Y en ese sentido, sí, es una película para pensar.

Fall 2009, Volume VIII, Number 3

Haden Guest is the director of the Harvard Film Archive.

Haden Guest es director de Harvard Film Archive.

Related Articles

Coconut Milk in Coca Cola Bottles

Common knowledge has it that virtually any movie, once removed from its original cultural context of production and reception, might be either misunderstood and misperceived or re-interpreted and re-signified. Likewise, we may agree that national cinemas seek to define, challenge….

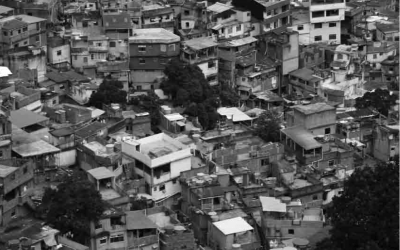

Neither the Sertão or the Favela

To frame the poetics of the ordinary in terms of subtlety and delicateness is to propose an antidote both for cynicism and for what I call Neo-Naturalism. Its appearance, at least in Brazilian cinema and literature, has been clearly identified, ranging from peripheral subjects…

Brazilian Cinema Now

Snow falling in the city of São Paulo, in southern Brazil? Taking a helicopter in São Paulo then arriving a few moments later in the deep wilderness of the Amazon jungle, half a continent further away to the north? Then meeting a white Asian tiger in the heart of the Amazon forest?…