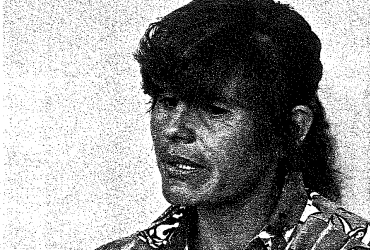

Ana Maria Sanchez: A Profile

Transforming Literature, Transforming Life

My first image of Ana María Amar Sánchez is of a bundle of joyous intellectual energy wrapped up in an incredibly soft blue-and-green Uruguayan shawl.

Amar Sánchez, a Harvard Associate Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures and a native of Buenos Aires, Argentina, entered my office for an interview, and almost immediately began to teach and delight and somehow gossip, almost all at the same time. She tells me about her ongoing work on popular culture, the kind of culture often associated with women, the romance novels, the soap operas, melodrama, pornography, various types of kitsch.

She talks about the ideological function and validity of popular culture, and I immediately assume she’s talking about a polarization of popular culture–often targeted at women–and high literature, read and written by both sexes but generally associated with an elite and perhaps masculine culture. It’s nothing as simple as that: she is seeking to establish the networks with which popular and high literature interact, in a kind of interactive dance she frankly calls “strategies of seduction and betrayal.”

In her forthcoming book, Games of seduction and betrayal: the relationship between literature and mass culture (Editorial Beatriz Viterbo, Rosario, Argentina), she intends to demonstrate the way high literature uses the genres of popular culture and manages to twist its codes and subvert its elements. This process of mutual contact between ‘high’ literature and popular forms is a constant in the history of Latin American literature, according to Amar Sánchez.

Her forthcoming book looks at topics ranging from the genre of detective fiction for the past 30 years to the correlation between kitsch and vanguard, “bad taste” and canon; she’s looking at the works of José Donoso, Mario Vargas Llosa, and Alberto Fuguet writing in the genres of romance novels, melodrama, and pornography. I imagine her academic life in the typical pattern of many women scholars, 20 or 25 years of constant studying, research, publishing, conferences, teaching, maybe a little slowdown for childrearing, maybe not.

I ask her how she became interested in this interplay between popular culture and high literature. The answer was somewhat unexpected. She did her doctoral thesis at the University of Buenos Aires on the disappeared Argentine journalist Rodolfo Walsh, a prolific author of detective stories.

“I was interested not only in his politics, but in his literature,” she recounts. “His books had disappeared from the libraries and the bookstores. I thought it was impossible. Then a friend said she had one book and brought it to me all wrapped up and hidden inside another book as if you couldn’t carry a book by Rodolfo Walsh. It’s how you live in a concentration camp that doesn’t appear to be a concentration camp.”

Living in Argentina during the dictatorship was a double burden for women. It was easier for men to leave the country, because women had to get permission from their husbands “patria potestad” to take children. “We women suffered doubly because the regime didn’t favor women’s liberation,” she recounts. “We suffered the political situation, and the impossibility of options. We couldn’t go to the university if we didn’t want to collaborate with the regime. We couldn’t divorce because we couldn’t support ourselves and because divorce didn’t exist. And we often couldn’t leave because of patria potestad. And I had a little boy.”

During those dark years, she began to attend a parallel university, a series of study groups, many of them run by women, that moved from place to place to escape notice. This was a university without any degrees, preparing her, as she says, “for a future I didn’t know if it would happen.”

The future did happen. With the end of the dictatorship and the opening of the universities, she resumed her formal studies. In 1985, Ana María Amar Sánchez received her doctorate.

“The world opened up doubly for women. When the dictatorship was over, my CV was non-existent. The only thing I could put on there was 10 years under a dictatorship. In 10 years, I accomplished in my career what most do in 20,” she declares. “I am not alone. All my generation did their doctorates 10 years late. We are a generation of women who did it alone and with a great deal of strength.”

The women of Argentina survived and many emerged from the dictatorship healthier than many men, because they engaged in “an unconscious system of resistance,” says Amar Sánchez. Suddenly, her work and experience seem to come together for me. Who can understand parallel codes and tacit subversion in literature better than one who has experienced them in life?

Winter 1998

Related Articles

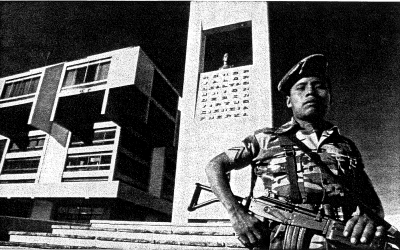

Interviewing Military Officers

We drove up into the residential hills of Villa Hermosa, overlooking the city of Guatemala, searching for the house amongst the many white-stucco, high-walled mansions. I asked the taxi-driver …

Disobedient Autobiographies of Las Desobedientes

From the quasi mythical conquista-age Malinche to contemporary women such as Rigoberta Menchú and Rosario Castellanos, Las Desobedientes restitutes the women of Latin American history …

Delivering the Data

Marta was 18, living at home in El Salvador, when she dated a man who raped her. She told her father about the rape, and he responded by threatening to kill her for damaging the family’s …