At the Movies

Lisandro Duque, the director of the film “Los niños invisibles.” Photo courtesy of El Espectador.

In 1993, Colombians were not unused to seeing President César Gaviria on national television giving the latest reports on the wars on drugs and against the guerrillas. This time, though, the President had something else in mind. He was appearing in a commercial for La Estrategia del Caracol (The Strategy of the Snail), the latest film from well-known Colombian director Sergio Cabrera. The President’s appeal worked. For the first time, Colombians turned out en masse to see a nationally-produced film, quickly making the movie a major box-office success. The domestic success of Cabrera’s film followed the first-ever selection of a Colombian film to the Cannes Film Festival in 1990, Víctor Gaviria’s Rodrigo D. Many believed the Colombian film industry was on the road to a bright new future.

Colombia, with Latin America’s third largest population, hosts major film festivals like those in Cartagena and Bogotá. It has produced internationally acclaimed directors and its film industry has periodically received state support. Nevertheless, technical limitations, monetary constraints, uneven production quality, and a lack of support in the domestic market historically have plagued the industry.

The Colombian film industry thus far has failed to reach maturity and dynamism. Despite the notable successes of the early nineties, by 1994 we find Cabrera himself confessing to the press that: “Colombian cinema does not exist.” Today, almost ten years later, do these words hold true?

A Historical Overview

The optimistic outlook of the early 1990s was not a new phenomenon but part of a pattern of such periods throughout the last century. At the beginning of the 20th century two Italians—the Di Domenico brothers, pioneers of the Colombian cinema— confidently proclaimed that “cinema production in Colombia is as easy as anywhere else in the world.” During the next three decades, the Di Domenicos and other Colombians created production companies throughout the country with high hopes, but their successes were ephemeral. In an environment that lacked sufficient funds, technical support and state aid, these companies quickly ended up bankrupt with little to show for their expectations. In reality, by the end of the 1920s the Colombian film industry no longer existed and Cine Colombia, the one successful company that had emerged during the decade, was dedicated solely to importing and distributing foreign movies rather than supporting local production. The arrival of sound greatly widened the gap between limited amateur domestic productions and more sophisticated movies coming from abroad. Indeed, it was not until 1941, almost two decades after the arrival of sound to the movies, that the first Colombian talking feature film was produced.

During the next decades all efforts made to recover the Colombian film industry were in vain. Only in the 1970s, when the state began to finance cinematographic productions in the country, did the optimism rise again. A surcharge law (ley de sobreprecio) came into effect in 1971to support the production of short films through an increase in movie ticket prices. The law also provided for the exhibition of a domestically produced short film alongside every feature presentation. The production of short films went into overdrive, and many young directors were able to find a forum for their work, though the general quality of the shorts was not high.

Around the same time, a new wave of filmmakers began to spring up around the country independent of the state-sponsored industry. This younger generation, pioneered by Marta Rodríguez and Jorge Silva, started to produce highly critical documentaries about Colombia’s social and political situation. Others, including Víctor Gaviria, worked on low budget experimental productions using super-8 and 16-millimeter film. And as feminist consciousness emerged in the country, Cine mujer (Women’s Cinema) was created as a feminist media collective promoting awareness of the needs and demands of Colombian women, later evolving into a successful independent production company.

At the end of the 1970s the state-owned company FOCINE, Compañía de fomento cinematográfico, was founded to spur the production of feature films. Over a decade, FOCINE financed and co-produced several films, yet despite some significant successes proved to be an extremely unprofitable and inefficient institution. FOCINE did not withstand the first round of privatizations that swept the Colombian economy during the early 1990s.

The Industry Today

Colombia’s state-sponsored cinema died with FOCINE, and new initiatives were desperately needed if the Colombian film industry was to regain life. The impetus came independent film producers, young and old, and their desire to continue creating new films dealing with the rapidly deteriorating socio-political reality of life in the country. Marta Rodríguez, who has been making documentaries in Colombia for the past 30 years, is convinced of the vitality of the documentary movement, citing the emergence of two new groups of young video producers in Medellín and Cali. The work of this “narcotraffic generation,” as Rodriguez calls them, gravitates toward the realities of inner-city violence in present-day Colombia. Their videos focus on the death, kidnappings and generalized violence that afflict modern Colombia.

Additional initiatives are now shaping and enriching Colombia’s filmmaking. These endeavors are creating opportunities for the community to reflect upon its cultural identity and social reality through films. Daniel Piñakué, a former guerrilla turned documentary and television filmmaker, encourages indigenous communities to use audiovisual media to portray their own communities and leave historical evidence of their present lives. Indigenous communities from the interior have begun to make documentaries, especially in digital format, through their own foundation, Sol y Tierra (Sun and Land). Likewise, Catalina Villar, a Colombian filmmaker living in France, has worked on another significant project since 2000: Talleres Varan en Colombia. Collaborating with the French embassy in Colombia and the Colombian Ministry of Culture, the project has been running film workshops for a new generation of young filmmakers. The participants in these workshops have started to produce excellent pieces that are now distributed both locally and abroad.

Colombian filmmakers have also found useful venues for their work in new domestic film festivals. One example is the annual Santa Fe de Antioquia video and film festival, which had its third exhibition, entitled Colombian Cinema, Memory and Oblivion, in December 2002. This festival also engaged the community, running several open workshops on film production and appreciation. In addition, for the past four years Alados (Association of Documentary Producers of Colombia) has been organizing an international documentary show, Muestra Internacional Documental, and this year Monogotary, a Colombian cinema distribution company, is organizing their second documentary festival, Toma Cinco (Take Five).

Television has become another important medium for the dispersion of new productions. University-owned, regional and national channels have become an open forum to exhibit new documentaries produced in the country, offering filmmakers from indigenous and other ethnic minority populations slots to present their productions. Very significantly, the Ministry of Culture and the national channel Señal Colombia created a miniseries, Diálogos de Nación (National Dialogues), that deals with a variety of contemporary national issues, and an educational series about film appreciation, Imágenes en Movimiento (Images in Movement).

While all these efforts, just a sample of what Colombia is producing today, are a very encouraging sign that film production is still alive in the country, in terms of production quality and quantity there remain huge roadblocks to the Colombian film industry attaining its potential. Marta Rodríguez points out that despite this moment of great creativity in Colombia, state support is still much needed, as lack of resources has limited production: “There is a movement, but we are far from producing what we should be producing in a moment of crisis,” she explains. State support for filmmaking is actually declining at present. The cinematography office of the Ministry of Culture offers less support. Where there used to be four or five awards to assist in the production of documentaries, now there is only one. This, Rodríguez concludes, points to veiled censorship by the government, which offers no economic support to projects that deal with thorny issues such as internal displacement or massacres.

To Lisandro Duque, who has been making films in and about Colombia for many years, the situation is stark: “Over the last few years there has been the appearance of high levels of productivity in Colombia, but this is just that, appearances. On average there have been one and a half productions each year. We are still waiting for dozens of young producers to wrap up projects they began five or six years ago. Last year, people were saying that there were 18 movies produced, yet nobody said that they began being filmed almost six years ago.”

According to Duque, producing a film in Colombia now is a quixotic activity. “If you get support from the Ministry of Culture, you might expect to receive close to $60,000, compared to the $150,000 we used to receive two years ago. Then you have to go to Ibermedia, the only international organization that is funding anything these days. There you might expect to get a reasonable loan of around $170,000. For the rest, you have to renounce your salary as scriptwriter, movie director, and executive producer. You are just gambling that the movie will break even and then produce some extra money to cover the investments.” The completion of a film isn’t the final challenge for Colombian filmmakers, who face considerable challenges distributing their work because, as Duque explains, the cinematographic division of the Ministry of Culture has no money for distribution. Duque’s frustration with the situation is almost tangible and he bemoans the fact that “there are several movies that could not be taken overseas for distribution, they are just briefly exhibited locally and that is it.”

Prospects

The most recent governmental attempt to help the Colombian film industry began in 1997 with the approval of the Ley General de Cultura (General Culture Law).This law created a new entity, Proimágenes en Movimiento, that united the efforts of the public and private sectors to encourage and facilitate Colombian film production. But the founding of Proimágenes coincided with the worst economic depression ever to hit the country and has yet to be the engine that will drive the Colombian film industry into the future.

According to special projects director Andrés Bayona, Proimágenes is not yet in a position to support any new productions. Though hampered by a lack of resources, they are striving to market Colombian movies by putting together a catalog of films distributed both in the country and abroad and producing a virtual bulletin with the latest Colombian film industry news. They are also focusing on distributing a selection of Colombian movies called the Maleta Itinerante (Itinerant Suitcase) at home and abroad.

Notwithstanding these activities, Proimágenes is most concerned with trying to work out the practical details of a draft law designed to protect and foster the production of movies in Colombia. “Proimágenes,” Bayona explains, “is the meeting point of all the different sectors that are related to the movie industry in Colombia and we are all together waiting for this draft law to become a reality.” The project intends to channel all the money from ticket sales back into the movie sector. Proimágenes will solely administer this money, thus preventing its dispersion into other branches of the administration. The institution will be in charge of providing loans and other aid to those seeking to produce new cinema, but in the hopes of not repeating FOCINE’s mistakes will not be permitted to co-produce movies.

Sergio Cabrera once said that Colombian cinema was a field with just one tree where at least a small forest should exist. We might say that now there are new trees growing in this field with the hope that in the near future we might be able to talk of a Colombian cinema. This glimmer of hope comes from the emergence of new festivals and new creative projects, the recent international recognition of several Colombian productions, and the perseverance and talent of well-known and new directors alike. Perhaps it is too soon to proclaim a renaissance. But the rise of a new diverse community of filmmakers, new legislation designed to protect and stimulate new productions, a more receptive, engaged and educated audience, and the availability of new and cheaper production formats readies Colombian cinema to speak with multiple voices and explore new avenues of development. While the transformation and recasting of the Colombian movie industry into a tool of peace and democracy may seem snail-like, there is hope that at last there is real strategy.

Claudia Mejía is a Lecturer in Romance Languages and Literature at Tufts University. She has hosted an annual Colombian Film Festival there since 1999.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter

This is a celebratory issue of ReVista. Throughout Latin America, LGBTQ+ anti-discrimination laws have been passed or strengthened.

Editor’s Letter: Colombia

When I first started working on this ReVista issue on Colombia, I thought of dedicating it to the memory of someone who had died. Murdered newspaper editor Guillermo Cano had been my entrée into Colombia when I won an Inter American…

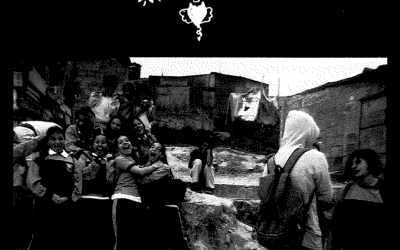

Photoessay: Shooting for Peace

Photoessay: Shooting for PeacePhotographs By The Children of The Shooting For Peace Project As this special issue of Revista highlights, Colombia’s degenerating predicament is a complex one, which needs to be looked at from new perspectives. Disparando Cámaras para la...