Barrio Adentro

A Look at the Origins of a Social Mission

Barrio Adentro, a social program that has expanded throughout Venezuela providing health care to city slums and rural communities, started in the Caracas municipality of Libertador—which includes slums with extreme poverty and high population density. In 2002, the Local Development Institute (IDEL), an agency responsible for social programs in this municipality, found in a door-to-door survey that the community’s pressing needs included transportation to get to a hospital in an emergency, better food to combat malnutrition, and opportunities to play sports. It had been a difficult year to obtain health care. The paro médico, in which doctors went on strike for better benefits and wages, caused most of the country’s outpatient clinics and public hospitals to shut down or open only for brief shifts.

In January 2003, the Libertador City Hall began advertising positions for medical doctors, seeking to launch a comprehensive health program that would go deep into the slum (barrio adentro) and that would rely on the permanent presence of doctors. The new program would also include an education program and sports activities. However, the Venezuelan Medical Federation, which had sponsored the national strike, pressured its members not to apply for the jobs, and only a few did so. Most of the doctors refused to live in the slums, citing union issues related to hazardous working conditions. A month later, the Libertador City Hall contacted and met the Cuban Medical Mission, which had been providing humanitarian aid in Venezuela since December 1999, following a major flood in the state of Vargas. Since then, a number of Cuban physicians had remained to help develop a comprehensive health program in places of great need throughout the country. The meeting led to the signing of a technical cooperation agreement between Libertador and Cuba.

In 2003 alone, Barrio Adentro handled 9,116,112 patient consultations and performed 4,143,067 health education interventions. How did this local program grow to become a nationwide social mission? To provide an answer, in 2006 the Pan American Health Organization and the Ministry of Health of Venezuela invited me and others to join a commission to document the functioning of Barrio Adentro. Although I had never worked in Venezuela before, I had the experience of several years of conducting research on the Cuban health system as part of the collaboration between Harvard University and the Institute of Tropical Medicine Pedro Kourí in Havana, initiated in 2001.

Arrival Of The First Cuban Physicians In Barrio Adentro

In mid-March 2003, a team of three Cuban physicians began to work with IDEL to develop what was then called the Barrio Adentro Plan. The Cuban team met with slum residents—some of whom were organized in urban land committees—to explore possibilities for housing some 50 Cuban doctors and setting up dispensaries in the homes of people who offered space. As a result of this consultation process, the slum communities became organized into groups that later evolved into health committees—representatives elected in open neighborhood meetings that share a dispensary (consultorio popular) and assist the physician in his or her preventive and educational health activities.

The Cuban team spent a month visiting homes of people who had volunteered to participate. Despite their poverty, most of the slums had access to electricity, running water, and wastewater disposal, particularly since the creation of the Mesas Técnicas de Agua in 2000—aimed at working with the communities to make drinking water available—which proved a major advantage for the growth of Barrio Adentro. The condition to host a doctor was to be able to offer a bed and a bathroom. To host a dispensary, they needed to offer enough space for a stretcher, a table, two chairs, and a curtain. Residents donating space had to allow access to any person in the slum regardless of social status or political affiliation, and all care had to be provided free of charge to the patients.

All Cuban physicians participating in Barrio Adentro, with an average of ten years of experience in Cuba and abroad, had to be specialized in comprehensive general medicine, a residency program that lasts three and a half years and includes internal medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics, and preventive medicine; more than 30 percent of those who went to Venezuela had a subspecialty and more than 70 percent had additional specialization.

By the beginning of April, the Cuban team, working closely with IDEL, found space for 50 doctors, who arrived in mid-April. Their impending arrival had generated a mix of high expectations and skepticism, because the slum communities could not believe that a political promise would materialize so quickly. In the words of one of the first Cuban physicians to arrive in Caracas:

When we arrived in the slums, people could not believe that we were there, because they told us that many administrations had come and gone and made many promises. Everyone had come and promised them something, and then afterwards nothing had changed. When they saw us, they couldn’t believe their eyes, because they had assumed that it would be just one more broken promise.

Some of the promised spaces were not even ready when the physicians arrived. However, the communities mobilized to meet the challenge, and within a day the housing was arranged. According to one of the first people to welcome the Cuban doctors:

They came straight from the airport to our homes. We were expecting them. We had gone to a lot of trouble to get everything ready, with a lot of embarrassment, but with great tenderness and care. And they quickly settled in.

The communities that welcomed the first doctors, fearing that they were not going to stay long and knowing that the living conditions they offered were not very grand, started to look for more opportunities to expand the program and improve the housing and working conditions for the doctors. Some neighbors donated mattresses, curtains, tables, and other utensils to improve conditions in the dispensaries; others donated food. Those who took part in this momentous effort look back on it as a challenging time but one that led to major achievements in claiming the right to health—and in building social cohesion in slums whose residents used to fear and mistrust their neighbors.

During the morning and into the early afternoon, the doctors took care of all the people who came, at first about 80 a day. Later in the afternoon they would go into the hills (cerros) to take a census, one household at a time, recording prevalent diseases, immunization histories, and nutritional status; identifying the main social problems such as illiteracy and overcrowding; verifying the availability of drinkable water and food; and, in the process, seeking out new places to accommodate the more than 150 doctors who were about to arrive.

The physicians reported their findings to the Barrio Adentro Coordinating Team, a team of Cuban epidemiologists stationed in Caracas. The epidemiological information system painted a thorough picture of the health situation in the slums, about which very little had been known until then. The two main social problems that were identified were malnutrition and illiteracy.

As the Cuban doctors treated both acute and chronic cases, the communities began to trust them. Up until then, many people in the slums had distrusted the doctors who had taken care of them in the emergency rooms of Caracas public hospitals. Many others had never known a doctor who would make house calls. This situation got even better when free medications became available in the dispensaries.

More than 100 additional doctors arrived in May 2003. They were sent to other slums in the hills of Libertador and to other parts of Caracas, such as the municipality of Sucre (another hilly area in the state of Miranda) and downtown Caracas. As new doctors arrived, they reached deeper into the communities, thus reducing the population that had been historically excluded from access to health care.

In December 2003, the Plan Barrio Adentro was established by decree as the first Social Mission, published a month later in the Official Gazette—by which the government decided to extend Mission Barrio Adentro to all of Venezuela. Barrio Adentro reached beyond the metropolitan area of Caracas to incorporate the state of Zulia; the rest of the municipalities in the state of Miranda; the states of Barinas, Lara, Trujillo, and Vargas; and, ultimately, the rest of the country. Barrio Adentro gradually became organized throughout Venezuela into its current administrative structure, in which health committees help draft health policies, plans, projects and programs, as well as carry out and evaluate the mission’s management.

Some Obstacles

While doctors and communities were fighting against disease and malnutrition, Barrio Adentro also confronted a mass media campaign against the presence of Cuban physicians in Venezuela. For political reasons, the Venezuelan Medical Federation spread word in the media that the Cuban physicians were not trained to practice medicine. However, the signing of an agreement with the Metropolitan District Medical School in May 2003 legally validated the qualifications of foreign physicians to practice medicine within the Barrio Adentro framework. The Federation responded by filing suit, and the Court decided that the Cuban physicians could not practice medicine in Venezuela. The media announced that the Cuban physicians had to leave the country, news that generated a groundswell of support for Barrio Adentro. The Metropolitan District Medical Association defused the situation by explaining that the Cuban physicians were not filling jobs but rather were on a humanitarian mission. However, the campaign created mistrust and made it harder for the Cuban physicians to convince patients to trust their diagnosis and recommendations.

Another obstacle involved medical prescriptions. Physicians arrived with drugs, but not always enough, leading them to prescribe drugs to purchase in pharmacies. Some did not want to fill the prescription if it bore the municipal and Barrio Adentro logos. Three weeks after the Barrio Adentro plan had started, Cuba shipped a more complete supply of 55 essential drugs. The municipal office provided a storage area, and the Cuban physicians took turns packaging and distributing them to every Cuban physician in Venezuela. In January 2004, based on health data collected, a group of 106 essential drugs began to be distributed twice a month to every Cuban physician in the entire country. The Venezuelan Armed Forces provided logistical support.

Since the conventional health system opposed Barrio Adentro, most of the public hospitals refused to receive patients referred by Cuban doctors. The Caracas Military Hospital, followed by the Caracas University Hospital, were the only ones early on that accepted referrals from Barrio Adentro for either diagnosis or hospital care. To expand the referral network, in mid-2003 the National Commission of Venezuelan Physicians created a directory of physicians in various public hospitals who were willing to cooperate with Barrio Adentro and receive its patients. This extra-institutional network was in the process of being formalized in October 2004, when a new mayor of Greater Caracas was elected and lent his support to Mission Barrio Adentro, establishing official links with the city’s Health Secretariat.

Toward Comprehensive Health Care

The use of private homes as dispensaries and to house doctors was a temporary way of addressing the urgent need to serve the population in the slums. More formal structures needed to be created to develop Venezuela’s National Public Health System. In August 2004, Barrio Adentro, in collaboration with local communities, began the construction of the first health modules—simple rectangular or octagonal brick structures that provide both dispensary space and housing for medical personnel within the community. Their location was chosen so that they would serve between 250 and 350 families. The dispensaries are backed up by centers of higher level of medical complexity: comprehensive diagnostic (Centros de Diagnóstico Integral or CDI), high-technology (Centros de Alta Tecnología or CAT), and comprehensive rehabilitation (Salas de Rehabilitación Integral or SRI) centers.

In the process of building the Barrio Adentro modules, the communities, working together with the Ministry of Health and with the Cuban Cooperation, became involved in activities ranging from certification of the land for location of the modules to approval of the decisions in town council meetings. Through these activities, community members have been building social networks, helping make decisions about public policy, and developing a culture of ownership and collective participation in activities that seek solutions to improve the quality of life in poor neighborhoods.

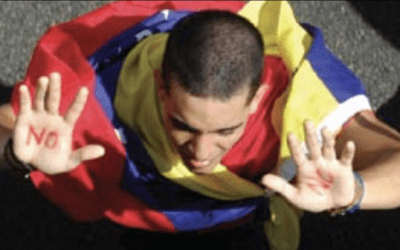

Barrio Adentro achieved in a short period of time the materialization of the right to health care for millions of Venezuelans. For others, it is seen as an instrument to “cubanize” the Venezuelan society and to turn health checkups into votes for the governing party; some fear that the success of Barrio Adentro may preclude private medical care in the not so distant future. Because the existence of Barrio Adentro relies on community organization, it is undeniable that the program has created a new space for political participation and activism that has forcefully extended throughout Venezuela. Whether the change is seen as the onset of socialized medicine or as the response to a historical social debt, the lives of many have taken paths that will be hard to reverse.

Arachu Castro is Assistant Professor of Social Medicine in the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine at Harvard Medical School and co-director of the Cuban Studies Program at Harvard University. The article is based on the interviews she conducted in Venezuela in 2006 while doing research with the Pan American Health Organization for the book Barrio Adentro: Derecho a la salud e inclusión social en Venezuela (Caracas: Organización Panamericana de la Salud, 2006), in which she worked in collaboration with Renato Gusmão, María Esperanza Martínez, Sarai Vivas, and others. She has published two books and several articles in medical, public health, and anthropology journals.

Related Articles

Plants Under Stress in the Tropical High Andes: Learning from Venezuela and Beyond

Tropical mountains are privileged places for ecological studies. Going up and down the slopes, like the ones surrounding my home town of Merida, Venezuela, we may simulate changes in temperature. While moving from one slope to the next or moving along seasonal precipitation gradients, we may study plant responses to water availability. These studies have shed light on identifying possible climate change effects on …

A Design Revolution: Caracas on the Margins

We write with a sense of urgency as we hear the deafening sounds of the city. When we read that the price of oil has rocketed to more than $140 a barrel, here in Caracas we are reminded of the impact of oil on the development of our city, first by despotic petro-populist development and later by hyper real petro-dollar development. Caracas continually faces blind building aggregation and arbitrary political decision-making, but …

Forum Venezuela: Moving Students, Student Movements

Harvard’s Forum Venezuela, a student-run organization, seeks to promote awareness of Venezuelan issues and culture, while connecting Venezuelan students living inside the United States both to each other and with their countrymen and women back home. The Forum was founded in the mid-1990s by Kennedy School of Government students who wanted to reach out beyond the confines of the school and to the sizeable but …