Beautiful Trash

Art and Transformation

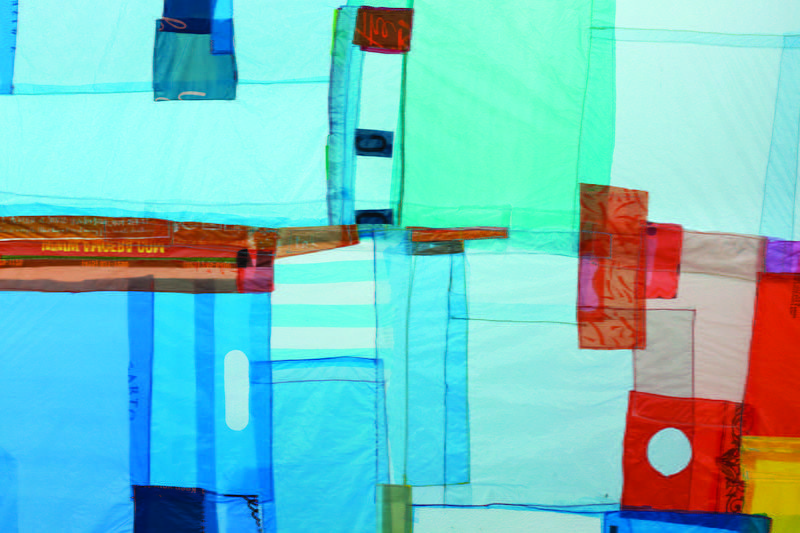

Detail, Forever; Blue Yonder by artist Kyle Huffman: another example of recycled art, this time form colorful textiles. Art by Kyle Huffman, courtesy of the artist.

The river bears no empty bottles,

sandwich papers,

Silk handkerchiefs, cardboard boxes,

cigarette ends

Or other testimony of summer nights.

T.S. Eliot, The Waste Land

(New York, London: W.W. Norton, 2001)

It’s the night before collection day. The trashcan is full of rancid food mixed with wilted waste and rotten flowers. Pull the red string fast, tie a knot, and put in a new bag: empty, white and odorless. The paper bag with recyclables is filled with flattened cardboard, rinsed plastic containers, envelopes and beer bottles. On the street, the public bins are lined up on the sidewalk—late at night comes the sound of glass and cans collected by people that sell them to make a living. But, while everything gets emptied into the garbage trucks in the morning, the cycle of accumulation has already begun at home.

We relate to garbage daily. We use it, produce it and dispose of it. Endlessly. The most obsessive of us get rid of it as fast as we can. The hoarder likes to salvage a few things for later use—the plastic and glass containers, the cardboard boxes.

Talking about trash sparks a discussion about society and mass consumerism, on the increase as Latin America becomes more middle class. We know that capitalism’s escalating cycles of production, consumption and obsolescence keep worsening an already problematic relationship between humankind, waste and nature (not to mention social and economic relations). Despite a relatively increased awareness about consumption and its consequences, the pace at which we also acquire and dispose of material objects is exploding.

Particularly in the connection between garbage and the arts, I am interested in two questions. First, the issue of recycling as a general practice in the arts; and secondly, in the whole issue of representation —that is, representation of waste as subject, and representation (of waste or others subjects) through waste as material.

ART AND RECYCLING

Recycling has always been a common practice in the arts at least at a non-material level. From creating a world of words in literature, to rhythm and images in poetry, sampling in hip hop music, representation in the visual arts, or editing the illusory continuity of a film, art implies taking disparate elements (ideas, images, references, objects, etc.) and putting them together to form a new whole. Take and put. De-contextualize and re-contextualize. In that sense, art, as a system, is an act of recycling.

Although the strictly material dimension of recycling is commonly associated with the visual arts, especially sculpture, it can also be found in other art forms.

For instance, consider the Argentinean cooperative publishing house Eloísa Cartonera. Making books from waste cardboard results in a simultaneous reproduction of literary works at accessible prices (with the authors’ donated rights), and a production of an art object (the books themselves, with their rough cut edges and handmade painted covers) made of discarded materials. Some of them are preserved as art books at university libraries, while others circulate as literary pieces expected to disintegrate in time—something anticipated of the material they are made from.

Assemblage at a tangible level (that is, of actual physical objects) became evident with the transformation of visual representation introduced by collage in 1912. As pointed out by Clement Greenberg in his essay “Collage” in Art and Culture: Critical Essays (Boston: Beacon Press, 1961), Picasso and Braque incorporated, for the first time, extraneous materials into the surface of a picture in search for “sculptural results by strictly nonsculptural means.” In turn, Cubist collage gave way to what Greenberg refers to as the “new sculpture” or “construction-sculpture” that revolutionized the medium—from its materials to the techniques and compositional methods:

The new sculpture tends to abandon stone, bronze and clay for industrial materials like iron, steel, alloy, glass, plastic, celluloid, etc., etc., which are worked with the blacksmith’s, the welder’s and even the carpenter’s tools. Unity of material and color is no longer required, and applied color is sanctioned. The distinction between carving and modeling becomes irrelevant: a work or its parts can be cast, wrought, cut or simply put together; it is not so much sculptured as constructed, built, assembled, arranged. Clement Greenberg, “The New Sculpture,” in Art and Culture: Critical Essays (Boston: Beacon Press, 1961)

This new approach continued to develop in a context of increased industrialization and commodification of everyday life. Consequently, more radical challenges to conventional figurative representation in sculpture—and to the arts in general, including its institutions—were brought about by constructivism and, ultimately, by the readymade. By means of the readymade, Marcel Duchamp actively introduced the question of “the relation of utilitarian objects to aesthetic objects, of commodities to art,” as explained in Hal Foster, Rosalind Krauss, Yves-Alain Bois, Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, Art Since 1900 (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2011).

It’s been almost a hundred years since Duchamp’s most iconic and polemic readymade, Fountain, stormed into the art circuit in 1917. In contemporary art, the relationship between object and art has switched from the industrial object to just about everything, including a good amount of detritus.

REPRESENTATION: WASTE AS MATERIAL AND WASTE AS SUBJECT

Some artists use disposable objects as materials through which they construct their work. And sculpture, more than any other medium, allows the incorporation of discarded elements. For instance, sculptors Thomas Hirschhorn and Abraham Cruzvillegas both use debris as material, but they have quite different readings in regards to waste.

In his essay “Detritus and Decrepitude: The Sculpture of Thomas Hirschhorn,” Benjamin Buchloh distinguishes Hirschhorn’s altars and pavilion from other kinds of sculpture, namely the solid monolith, the serial structure or “the ready made analogue to the commodity.” He stresses not only the radical participatory potential of these sculptures—commonly placed in public spaces (low-income sites, public trash containers, and other peripheral locations)—but also the material they are made from: that is “detritus, the materials of waste and impoverishment.”

Too Too—Much Much, a massive sculpture by Hirschhorn exhibited at the Belgian Museum Dhondt-Dhaenens in 2010 is, as the title tells it, a reflection on the meaning of quantity. It consists of a huge amount of beverage cans overrunning the entire gallery space and pouring out the main door into the entrance garden. As described by Hirschhorn, the accumulation of cans signifies consumption and excess, but serves also as commentary on artistic practice and the desire to create more and more. Besides the mountains of cans on the floor, various elements are scattered throughout the gallery: mannequins, pieces of furniture, old electronics, aluminum foil figures, plastic bottles, pornographic magazines, stuffed animals, cardboard mock-ups of skyscrapers, Christmas trees, etc. Some cans are assembled as mass consumption figures such as machines guns, television cameras, masks and airplanes. The complete sculpture suggests a landscape very much like that of a landfill.

What Buchloh argues in his essay on Hirschhorn, is that detritus is an inevitable consequence of “the incessant overproduction of objects of consumption and their perpetually enforced and accelerated obsolescence [that] generate a vernacular violence in the spaces of everyday life.” While Hirschhorn is a Swiss artist, he speaks to the increasing perception in Latin America about encroaching commercialism and its consequences.

In contrast, in her forthcoming book The Logic of Disorder: The Art and Writing of Abraham Cruzvillegas (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015), Robin Greeley looks at the work of this Mexican artist and his project Autodestrucción, from the perspective of “the logic of disorder,” one that “locate[s] his aesthetic production not in a universally uniform experience of relentless commodification, but in the systemic connections between object experience in ‘peripheral’ nations…. versus that encountered in the metropolitan ‘centers’ of developed countries and the international art market.”

Thus, while Hirschhorn exposes debris and the logic of excess in our society (including art and the art world) as an inevitable production of detritus, the work of Cruzvillegas explores the imbalance between center and peripheral experience in today’s globalized societies. He works with the creative modes of subsistence developed by the later group, activating discarded objects to reflect improvisation and collaboration. In a way, we deal with two sides of the same coin: that is, excess and scarcity.

Cruzvillegas’s sculptures have the qualities of both perfect equilibrium and latent transformation. Installations such as Autoconstrucción (2009) and The Autoconstrucción Suites (2013) are constructed with objects of different shapes and materials (e.g. wooden boxes, metal buckets, discarded sections of chairs, wooden and metal beams, clothing, rubber tires, old television sets) assembled in a balance so precise it upsets the precariousness of the materials and the discontinuities between them. In Greeley’s words, Cruzvillegas’s “object misuse does not remain purely at the level of metaphor, but is structured as a system of aesthetic production that enacts specific procedures.” One of them being that “nothing is viewed as pure detritus; everything has a potential for reuse.”

On the other hand, photography frequently makes a representation of trash as subject matter. Two compelling examples are Vik Muniz’s Pictures of Garbage (2008) and Andreas Gursky’s Untitled XIII (Mexico) (2002).

Pictures of Garbage is a photographic project about the catadores (trash pickers) working at Rio de Janeiro’s landfill, Jardim Gramacho. Through a multilayered process, Muniz makes photographic portraits of some of these catadores, reproducing images of familiar masterpieces such as Jacques-Louis David’s TheDeath of Marat (1793). He then composes the images through a sculptural process—a thorough assemblage of colors, textures, forms and shadows—using garbage gathered from Jardim Gramacho. Once the image is completed, he photographs it and the object is discarded. What is left, that is, the final product, is the photographic register (see Lucy Walker, Waste Land [UK, Brazil, 2010]).

The photographs, seen from a distance, resemble the original image used by Muniz as reference. Thus, it could be concluded that they are not photographs of waste as subject. Nevertheless, when seen up close, what we have in front of us is, indeed, a picture of garbage.

In a similar register of images that create an illusion from afar that differs from the up-close complex details forming the whole, Andreas Gursky gives us a straightforward photograph of Mexico City’s garbage dump. Its particular framing, elevated perspective, and use of a very large format are consistent with Gursky’s overall aesthetics of creating grand landscapes composed of numerous details. Other projects by Gursky, for instance 99 Cents II Diptychon (2001) and Copan (2002), deal also with elements of mass culture (such as raves, stock exchange activity, multifamily buildings, subway stations, music concert, factories) and prompt reflections about consumer goods in contemporary society. However, in contrast to Muniz’s images, Gursky’s Untitled XIII (Mexico) is clearly a photograph of garbage.

Whether in sculpture, photography or other media, art frequently deals, directly or by allusion, with daily challenges of life in Latin America and elsewhere. This makes me think of the confines of our escalating creation and management of refuse. Illegal mining in regions such as Madre de Dios in Peru generates spaces of mud, pollution and abandonment, people indiscriminately scavenging resources without considering the consequences to the environment and their own health; toxic elements emanate from materials being shipped to China to be reduced to pure metal; and tons of plastic accumulate in the middle of the Pacific Ocean without the possibility of ever disintegrating. As described by Buchloh, “any spatial relations and material forms one might still experience outside [the] registers of overproduction of objects and of electronic digitalization now appear as mere abandoned zones, as remnant objects and leftover spaces…” In such a context, is there a limit to recycling and representation? Or is there a point at which waste cannot become art (or anything else)?

Autoconstrucción Room, 2009. Installation view, Thomas Dane Gallery, London. Installation of 15 objects; mixed media Variable dimensions Collection D. Daskalopoulos, Greece. Art by Abraham Cruzvillegas, courtesy of the artist.

Winter 2015, Volume XIV, Number 2

Paola Ibarra manages the Andes Initiative of DRCLAS at Harvard University, collaborates with the ARTS@DRCLAS program in Cambridge and manages the film component of the program. She holds an ALM in English from Harvard Extension School, and an MSc in Development Studies from the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Related Articles

Garbage: Editor’s Letter

Religion is a topic that’s been on my ReVista theme list for a very long time. It’s constantly made its way into other issues from Fiestas to Memory and Democracy to Natural Disasters. Religion permeates Latin America…

Buenos Aires, Wasteland

English + Español

Walking down Avenida Juan de Garay last week, I passed a giant black trash bag that had ballooned and burst. Orange peels, tomatoes, candy wrappers…

First Take: Waste

Waste—its generation, collection and disposal—is a major global challenge in the 21st century. Cities are responsible for managing municipal waste. Solid…