Behind the Corporate Veil

Company Control in the Lago Colony of Aruba

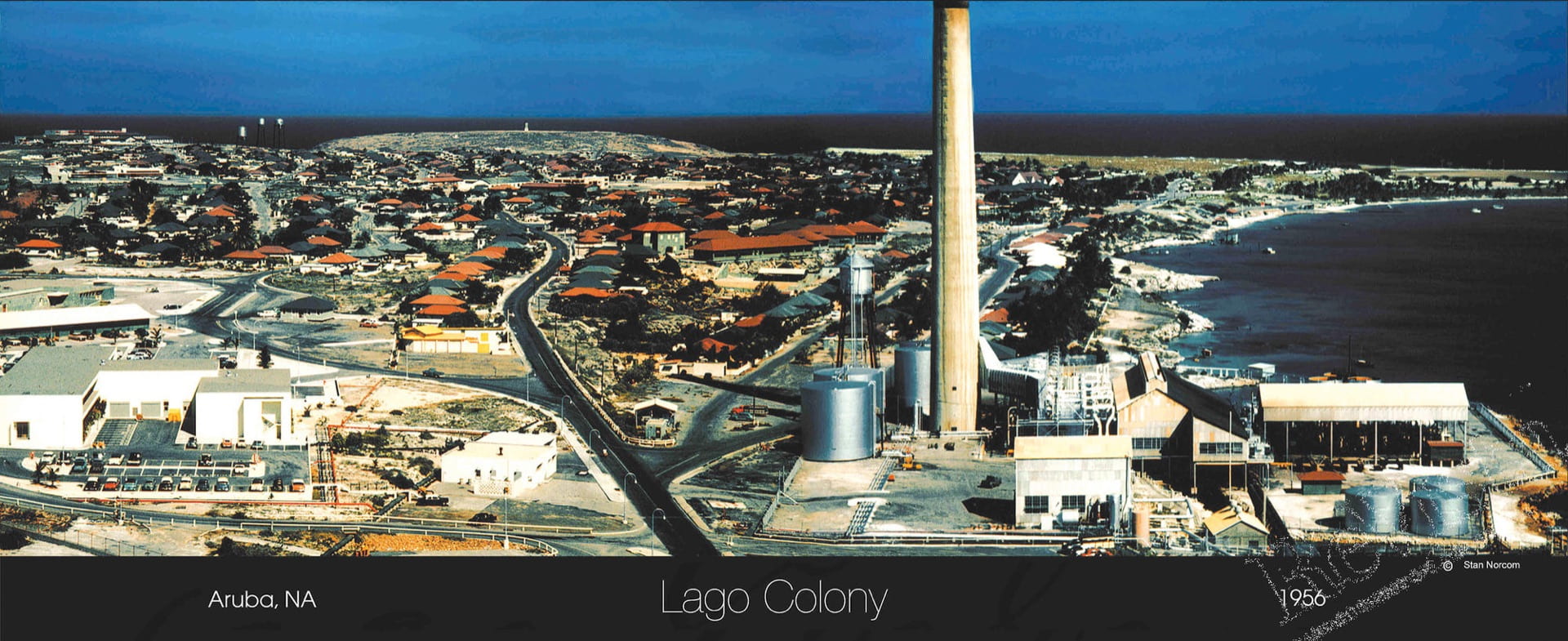

It began as most things do these days, with a simple Google search. Looking to flesh out my graduate seminar paper on the Lago Oil & Transport Company of Aruba, I typed the company’s name into that infamous search bar and prayed that those fickle gods of the Internet might have pity on me, a humble researcher. The title of a domestic court case caught my eye among the results. “Richard Mink v. Lago Oil & Transport Co. (05/02/66),” it announced promisingly, so I clicked on the link and began reading. An appeal before the Supreme Court of New York, “Mink v. Lago” held some startling allegations. Walter Mink, a U.S. citizen and former Lago employee, was suing the Aruban refiner for “improper medical care” given to his newborn son Richard in 1956. In the midst of a simple procedure, company doctors had misplaced an intravenous feeding tube, leading to disastrous consequences. “The fluid,” Mink explained emotionally in a 1965 court affidavit, “was not fed into the vein but into some other part of [Richard’s] lower right extremity…his ankle bones were literally ‘washed away.’” Lago doctors eventually had to amputate Richard’s right leg to prevent infection. It was a tragedy, the elder Mink maintained, leaving his son “sick, sore, lame, and disabled…and still suffer[ing] great physical pain and mental anguish.” He concluded his suit asking for $325,000 on the basis of his son’s disability and his own hardship.

This case was shocking, not only because of the lurid details of medical malpractice, but also because it stood at odds with community memory. Former U.S. expatriates were quite vocal about their attachment to Lago and the Lago Colony (1930-1985), their home on the island just north of Venezuela. “In my heart, I know where my true home is and always will be: that small desert island named Aruba,” Margie Pate said, remembering her time amongst the 3000 U.S. employees and their families. Eugene Williams agreed, recalling wistfully in 2003 that “when we left Aruba, it was like leaving paradise.” These bold assertions only made Mink’s experience all the more incomprehensible and, consequently, all the more intriguing. Could secret resentments possibly be hiding behind such fond remembrances?

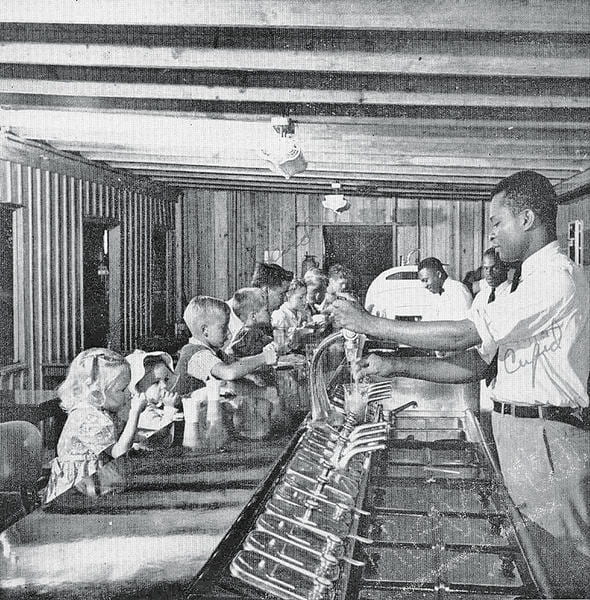

Not everyone, after all, evaluated Colony life quite so positively. Some female “Lagoites” balked at the gendered expectations foisted on them as part of island life. Company policy required teachers and nurses to give up their careers after marriage, presumably to focus on their wifely duties. “I do not do it wisely or well and I need [my husband] so badly to help me [raise our children],” Charlotte Warden wrote plaintively in her diary in 1947. Local residents on the payroll also resented Colony life, though more based on their exclusion from it, not their entrapment within. Local workers earned less money for equal work, prompting Guyanese draftsman Isaac Chin to complain that “my ceiling as a non-foreign-staff employee was barely above my head” (Where is Choy? 2002). Quality of housing openly demonstrated this disparity. Though given their own sports fields, commissaries and houses, Caribbean employees could readily see the luxurious lifestyle of those in the Colony, if only from a distance. Indeed, the company prohibited non-white, non-managers from entering the foreign enclave except to perform the service work such as gardening and cleaning that kept life in the Colony so leisurely. Thus, animosities abounded within and outside the Colony. These examples, however, fail to explain the travails of Walter Mink, the victim of neither sexist expectations nor racial limitations.

Indeed, Mink’s grievance went beyond issues of Colony inequality, touching instead on those of company authority. Lago’s local laborers well understood this reality. Many remembered the infamous strike of 1951. Though involving almost half of the refinery’s labor force, the protest had ended in failure, gaining only a limited wage increase and resulting in the deportation of several labor leaders. Assistance from the Dutch colonial government had guaranteed Lago’s victory. Royal Dutch Marines remained stationed around the refinery throughout the strike, a precaution meant to safeguard the facility that processed over 140 million barrels of Venezuelan crude oil each year, employed over 33% of Aruba’s workforce and accounted for over 90% of the island’s exports. This economic strength ensured government patronage in the years to come, perpetuating Lago’s dominance over unskilled Caribbean workers. Such power did not, however, appear to have affected the lives of Lago’s expatriates. These engineers, by virtue of their technical know-how, held more bargaining power vis-à-vis the company. Lago could not, for fear of losing valuable employees, implement the paternalistic practices so commonly associated with company towns (e.g. paying in scrip). Instead, it had to influence the Lagoites in more subtle ways, such as reserving certain community privileges like nicer houses, cars and Christmas trees for those with company standing and seniority. The skills of foreign engineers thus shielded them from the full weight of corporate power.

Or did they? The full story of “Mink v. Lago” hints at the true extent of Lago’s authority over its expatriate staff. Though beginning as a junior engineer in 1949, Walter Mink quickly rose through company ranks, eventually becoming a supervisor within the Marine Department. In 1957, upper management selected him for a prestigious taskforce examining off-the-job safety. The middling manager was particularly qualified for the role, and not just because of his rising ascendancy within the Lago operation: his son Richard had suffered that fateful accident the previous year. Initially, the medical malpractice seemed to have little effect on Mink’s relationship with his employer. He still worked for the company; Lago had assumed all medical expenses, promising to cover future treatment. The refinery upheld its part of the bargain, but only until Mink’s retirement in 1963. In the midst of corporate downsizing and scrupulous penny-pinching, Lago appears to have discontinued its medical payments. Mink sought legal redress, but not through the Aruban courts. What island official, after all, would dare prosecute the company that, in effect, paid his salary? To try and elude this extensive influence, Mink launched his suit in Queens County, New York. He offered an inventive argument as to how a court in New York could prosecute alleged wrongdoing committed in Aruba. Because of the extensive business conducted between Standard Oil of New Jersey (Lago’s New York-based parent corporation) and its Lago subsidiary, Mink claimed, the two companies were one and the same, separated only by a “fictitious corporation veil.” This argument, while imaginative, ultimately failed to persuade the judges. They ruled Lago and Standard Oil separate entities, dismissing Mink’s case based on a “lack of jurisdiction.”

This verdict illustrated the breadth of corporate control at the Lago Refinery and within the Lago Colony. The company dominated the political and economic affairs of Aruba, much like the notorious United Fruit Company of Guatemala. Indeed, such authority undergirded the very existence of the refinery and its staff enclave, government concessions given to Lago because of its economic value. Corporate patronage, therefore, joined the beautiful bungalows and pristine beaches as things essential to expatriate life, realities that made their time in the Colony possible, even enjoyable. Perhaps the most valuable aspect of this company power, however, was not its extent but its invisibility. The true extent of Lago’s authority remained largely unseen in the Colony, hidden behind the fond memories of expatriate living, the extensive privilege enjoyed in comparison to local laborers and, according to Mink at least, the false corporate veil separating Lago and Standard Oil of New Jersey.

Fall 2015, Volume XV, Number 1

Kody Jackson is a graduate student in History at the University of Texas in Austin. He studies religious movements in the Americas and U.S. Americans abroad in different capacities (business, missionary work, etc.). He would like to thank Dr. Jacqueline Jones and the Briscoe Center for American History for their assistance with this article.

Related Articles

Oil and Indigenous Communities

On a drizzly morning in late February, a boat full of silent Kukama men motored slowly into the flooded forest off the Marañón River in northern Peru. Cutting the…

Mexico’s Energy Reform

The small, white-washed classroom at the University in Minatitlán, Veracruz, was packed with a couple dozen people who, although neighbors, had never met…

Geothermal Energy in Central America

When we think about global technology leaders, Central America does not typically come to mind. But Central American countries have indeed been in the…