Between Bombs and Bombshells

Students and Sexual Politics in 1968 Brazil

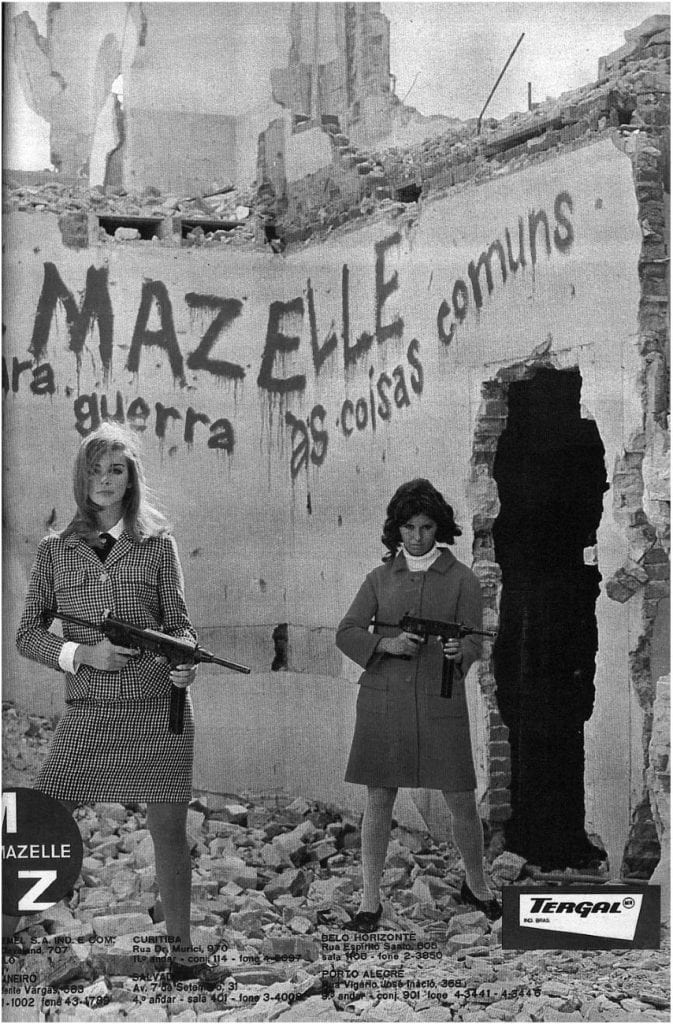

Attractive women with guns are used in advertising to promote such products as motor oil. sex- ualized advertisements expressed social anxieties about sexual activity and the rise of militancy. Photo courtesy of Victoria Langland.

Of the many dynamic political and cultural forces that marked Brazil in the 1960s, one of the most remarkable was the effervescent student movement, especially during the momentous year of 1968. University students in Brazil had a long history of organizing politically and participating in national issues. However, the student movement of 1968 was unlike its predecessors. It represented some of the intense transformations the country was experiencing, including new degrees of participation for women in the student movement and sweeping changes in gender and sexual relationships for young people more broadly.

Brazil had been living under a military dictatorship since 1964, when the armed forces overthrew then-president João Goulart in a not uncommon Cold War move on the part of business, military and other sectors. Many university students, like others from their middle- and upper-class origins, originally supported the 1964 coup. Nevertheless, by 1968, large numbers of them had turned away from the regime—vehemently so. This shift reflected a general discomfort with the regime’s gradual—and not so gradual—restriction of civil liberties, compounded by severe problems with the university system. It also reflected the growing leftward trend within the student body, a trend witnessed in other Latin American universities at that time. Students saw that the developmentalist economic programs of the last decades had produced few benefits, while the socialist turn of the Cuban Revolution offered new possibilities.

Eventually, students spearheaded the principal opposition movement to the regime, positioning student activism as essentially an “anti-dictatorship” movement. It’s worth noting too that in the four years since the coup d’état, the labor unions and peasant leagues active in the early 60s were decimated; political parties were rendered virtually obsolete; and while many other sectors of society opposed this military intervention in political life, there was very little space to express this opposition. Because of students’ relatively privileged social position, however, and because the regime at first did not believe many students really opposed them and were merely being led astray by a small group of outside and inauthentic “agitators,” they were able to take up their anti-dictatorship position. Student-sponsored protests during this time began to assemble record-breaking numbers of participants (including many non-students, such as musical celebrities, clergy members and others), and spurred intense press coverage and often repressive government intervention. Furthermore, students would make up a large portion of the newly forming underground organizations that arose in this period and advocated armed struggle and socialist revolution.

Women participated actively in both the university-based student mobilization and the growing, clandestine armed movements. While it is impossible to know exactly how many students in general and women in particular participated in these movements, we can make informed estimates. Thus, for example, , observers estimated that about 300 students attended the 1966 National Students’ Union meeting, and that one out of every ten students participating were women. Two years later, at the 1968 congress, police raided the banned meeting and arrested everyone there. Their records show that 712 students were arrested, and 22% of them were women. Judging just by participation in these congresses, this represents an overall increase in participation between 1966 and 1968 of 137% for students in general and a whopping 420% for women students.

Such a growth of female student activism clearly concerned some observers, especially once the student movement made a tactical decision to physically confront the state security forces as best they could. Since 1964 the police had gradually begun utilizing more drastic means to quiet dissenting students. If at first students generally sought to avoid the mounting physical repression unleashed against them, after a student protester was shot and killed by the police in March of 1968 they held prolonged internal political discussions about using violence and ultimately decided to not avoid confrontation (Maria Ribeiro do Valle, O diálogo é a violência, 24.). Thus, soon after, students began deliberately arming themselves for street protests with makeshift weapons like Molotov cocktails, rocks and corks hurled in slingshots, simple sticks and stones, or broken pieces of acetate records that, they said, could be thrown quite precisely at some distance. Meanwhile at some marches a few students would station themselves in some of the many high-rise buildings in the cities’ downtown areas, from which they could throw heavy objects at the police below.

This decision was confirmed by Olga D’Arc Pimentel, a student leader in 1968 from the city of Goiânia, who later recalled:

We decided to change tactics. You’re going to force us? Then let’s go, now everyone is going to go prepared. And we all did. The girls with bags underneath the skirts of their uniforms, full of rocks. Then when the army would start to line up, there came that rain of rocks. It was crazy (Daniel Aarão Reis and Pedro de Moraes, 68: A paixão de uma utopia, 153).

Although this change in tactics certainly represented a shift for the student movement in general, the active participation of female students proved even more unusual, for they had not traditionally engaged in much counteroffensive before this time. Only four years earlier, for example, on the day of the coup itself, a mixed group of students and artists went to the student union building in Rio de Janeiro to try to protect it from attacks. While some of the men armed themselves with weapons, the women of the group were to bring first-aid supplies, hidden inside their purses, in case anyone was hurt—not rocks under their skirts. Likewise, in June 1968 U.S. Embassy reports indicate that young women carried stones in their handbags to street protests and young people of both sexes brought sticks rolled up in newspapers.

Besides becoming more politically militant, students in 1968 began breaking down boundaries of another kind of activity: sex. As in other parts of the world, the climate of cultural and political change in the late 1960s led to considerable questioning of long-standing values concerning sexuality, while the technological advance of the birth control pill allowed young couples to act on their beliefs with much less risk of pregnancy. As two Brazilian historians who were themselves university students in this period have eloquently noted,

[T]he 1960s in Brazil witnessed a peculiar conjuncture. On the one hand, power was forcefully taken over by a portion of those Brazilians for whom “the dissolution of customs” was part of an insidious subversion engineered by the international communist movement. On the other hand, for the children of the post-war baby boom who were reaching adulthood, the order of the day was “questionings,” as we also used to say, of the disdainfully labeled “bourgeois marriage,” understood as the supra-sum of hypocrisy and of the inequality of erotic opportunities between the sexes (Maria Hermínia Tavares de Almeida and Luiz Weis in História da Vida Privada no Brasil: Contrastes da intimidade contemporânea, 399).

That this sexual questioning did not necessarily result in the equal freedom of sexual expression sought by progressive young women is made clear by the fact that even within the left, old sexual standards died hard, or not at all. Numerous young male activists echoed the confession of one student who admitted: “Many of us embarked on ambiguous projects, dating some ‘pretty’ girl from the Paineira or Paulistano [Country] Club and at the same time carrying on burning passionate affairs with colleagues from the university, political militants…” (Ibid, 370). Nor is this to say that all or even most university students were engaged in more open sexual activities. One woman remembers the advice given her at the time by her friend: “We have to act like we put out for guys, but we don’t really have to put out for guys” (Zuenir Ventura, 1968: O Ano que não terminou, 37.) Yet even if these explorations did not constitute the sexual revolution that some people either feared or hoped for, 1968 nevertheless marked a moment of broad sexual questioning, one felt throughout society.

These new sexual ideas and behaviors of young people provoked vociferous public debates and anxieties. A flurry of articles on topics such as sex education, abortion, birth control, and wearing bikinis filled the pages of newspapers and magazines. In one magazine article in Manchete magazine titled “Nudism and Sex: Is the world implanting a new morality?” the authors lamented this new “revolution of sex,…a type of atomic bomb, of highly explosive material, destined to destroy society and subvert customs.” Exaggerated or not, such sentiments were not uncommon and reflect the profound sense of unease that young people’s sexual explorations provoked.

The conflation of sex with revolution colored the way student activists were understood, especially women students. Following the early morning raid of the student congress mentioned earlier, the police held a press conference to show off the “subversive” materials they had confiscated. They directed journalists to tables loaded with displays of Molotov cocktails, slingshots, communist literature, knives, a few pistols, and several boxes of birth control pills. Indeed, those students who attended such gatherings found themselves not simply subject to arrest, but also the focus of much speculation regarding their sexual behavior. Attending a student congress or occupying a university building meant that male and female students slept overnight in unsupervised locations, sometimes for a week or longer. And journalists who covered these events invariably reported on the night-time arrangements, often alluding to their impropriety. At the raided congress, for example, great emphasis was placed on the fact that, due to lack of space, some students were found sleeping in an unused pigsty (the congress took place on a farm). The Secretary of Security declared to reporters of the Jornal do Brasilthat at the student meeting there was “total promiscuity. Boys and girls lived in the same tents, in the same pigsties [and] barnyard” (“Polícia paulista liga Congresso da ex-UNE a terrorismo e assassinato,” October 16, 1968). At another overnight event, students took over the Faculty of Philosophy of the University of São Paulo, where they remained for several weeks, forming study and discussion groups and holding impromptu courses on current events. A reporter who visited them gave scant attention to these academic activities, but duly described “the hotel” — the fifth-floor classroom where students slept stretched out on the floor or on tables pushed together (“A Faculdade esta Ocupada.” Realidade, August 1968, 56).

That parents ought to better supervise their daughters’ activities clearly seems to be part of the message the police were trying to send when they displayed birth control pills to the press. In a similar warning, the Army Chief of Staff told a newspaper in 1970 that young women typically got involved in subversive activities by way of young men who, after winning them away from their families, would “incriminate” them so that they could not return. In the same interview, he proclaimed “young terrorists” as very promiscuous, and categorically stated that rates of venereal disease and illegitimate births among them were high (cited in a telegram from the U.S. Embassy Rio de Janeiro to Secretary of State, Washington D.C., July 22, 1970).

From the display of birth control pills at the student congress to the idea that women joined clandestine groups via love affairs, the overall message sent by the police and press at once dismissed women’s political activities as poorly disguised sexual acting out while also, contradictorily, proclaiming that their political activities and sexual activities inevitably intertwined, thus warning parents and others to be wary of this double-pronged danger.

One further (and intriguing) expression of social anxieties about the rise of militancy and sexual activity among female university students can be found in magazine advertisements and fashion spreads from 1968. Beginning around April 1968, just as student protests were really heating up in Brazil and around the world, sexualized images of armed and/or persecuted women inundated the pages of the mainstream press. At the same time that reports of student activities decried the violence in which young people participated, the media began to display images of violent fantasies against young female bodies. The appearance of these images also suggests a form of repressive response, in this case to redefine women’s political struggles as sexual entertainment. For these images both paralleled interpretations of currently active women students and helped to create a template from which to read the armed actions that were soon to follow. And these popular conceptions of politically active women propagated in 1968 would arise again in the gender-specific torture and abuse of women political prisoners by the state security forces in 1969 and the early 1970s.

Victoria Langland is an Assistant Professor of History at the University of California, Davis, where she is finishing a book about 1968 in Brazil. This work comes from her article, “Birth Control Pills and Molotov Cocktails: Reading Sex and Revolution in 1968 Brazil,” in In from the Cold: Latin America’s New Encounter with the Cold War, edited by Gilbert M. Joseph and Daniela Spenser (Duke University Press, 2008).

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: The Sixties

When I first started working on this ReVista issue on Colombia, I thought of dedicating it to the memory of someone who had died. Murdered newspaper editor Guillermo Cano had been my entrée into Colombia when I won an Inter American Press Association fellowship in 1977. Others—journalist Penny Lernoux and photographer Richard Cross—had also committed much of their lives to Colombia, although their untimely deaths were …

The True Impact of the Peace Corps: Returning from the Dominican Republic ’03-’05

I am an RPCV: a Returned Peace Corps Volunteer. For me the Peace Corps was an intense life experience, above anything else. As I continue to reflect on it, I am struck with the many and varied ways in which it continues to affect my life. As a PCV in the Dominican Republic from September 2003 to November 2005, I lived, worked, and learned in a small sugar cane-dependent community two hours outside of Santo Domingo…

In the Shadow of JFK: One Peace Corps Experience

I am often asked about the Peace Corps by students and recent graduates. The most frequent questions are, “why join?”, “what did you do?”, and “what has it meant for your career?” Here is my story. My earliest recollection of international curiosity was in the fourth grade when Sister Margaret Thomas described her experience as a recently returned missionary in Bangladesh. In high school, my sister Mary went to Peru on …