A Review of Between Vengeance and Forgiveness

Facing History

Between Vengeance and Forgiveness: Facing History After Genocide and Mass Violence, by Martha Minow, Beacon Press, 1998

At the close of this century of death camps, killings fields and desaparecidos, there is perhaps no more urgent question than the one raised in Martha Minow’s useful new book: Can societies recover from mass atrocity without falling prey to the legacies of a violent past? “There are no tidy endings,” Minow sensibly observes, no safe way to respond to the unspeakable. The impulse to forgive–to “turn the page”–can be as dangerous as the bloodthirst for vengeance. Even the best intentioned institutional efforts–trials, truth commissions, and reparations–all potentially carry moral, legal, and/or political costs. The author, a Harvard Law Professor, parses these tensions clearly and systematically, in language that is accessible to a wide spectrum of readers.

Minow grounds her analysis in concrete history: the Holocaust, apartheid, the internment of Japanese-Americans in the 1940s, the Comfort Women of Korea. While she mentions more than once Latin America’s brutal military regimes, she is disappointingly vague with respect to names, places, and dates. Still, this book is valuable for Latin Americanists, because the issues are pressing–and controversial–from Guatemala to the southern cone.

“The logic of law will never make sense of the illogic of genocide,” holds Holocaust scholar Lawrence Langer, who is quoted early in the Introduction. Langer is correct, but so is Minow who argues that cynicism, bitterness, and outrage are engendered by legal inaction. The victims of crimes understandably look to the courts not only to punish criminals, but also to signal that moral safeguards are working. These needs are exceedingly hard to meet after national or international trauma. Minow points up the conflicts by looking at The Nuremburg Tribunal, which first defined “crimes against humanity,” gave rise to the UN Genocide Convention, and established the principle that nations cannot morally ignore savagery committed beyond their borders. Yet even Telford Taylor, the Chief U.S. military prosecutor, conceded that in pursuing justice against the Nazis, the Tribunal violated some essential legal principles. For one thing, the charges were codified after the events took place; the list of defendants was highly selective; and crimes committed by the Allies were never prosecuted. Minow argues that all trials are subject to being politicized, and that the adversarial process may be inherently unsuited to the gray areas of mass repression–crimes committed under duress, “bureaucratic massacre,” the passive complicity of civilians, the involuntary complicity of citizens paralyzed by fear. Trials by definition are spectacles of conflict with clear winners and losers, and this, argues Minow, can endanger recovery.

She believes that Truth Commissions are a better recourse, and uses South Africa as a prime case in point. In a trial, the objective is to separate the perpetrators, to mark their difference from the rest of society; a truth commission seeks reconciliation, even unity. Desmond Tutu emphasizes the African concept of ubuntu, which means “humaneness,” an inclusive sense of community based on respect for everyone. Far from being “soft on crime,” ubuntu depends on the assertion of human rights guarantees, and encourages the rigorous gathering of facts through the testimony of victims and the confessions of criminals granted amnesty from prosecution. In South Africa, more than 20,000 individuals have testified. The documentation gained here is likely more extensive, detailed and nuanced than that which could ever come out of a trial. The focus on victims confers dignity and respect, which is itself important for national recovery. So too is the therapeutic climate and discourse of the proceeding. Yet here too, Minow warns, there are potential side-effects: the emphasis on “victimhood” can “shortchange justice”; granting amnesty in exchange for truth can be conflated with forgiveness. It is crucial, she holds, to name names. The moral potency of a Truth Commission derives from its ability to expose what was hidden, to destroy the secrecy that engendered impunity.

Minow devotes a rather abbreviated chapter to reparations, apologies and memorials. As a form of official acknowledgement and documentation, reparations help weaken future attempts at denial. Reparation can also help to address the impotence felt by victims who lost not only loved ones, but cherished heirlooms and assets earned through hard work. Of course no sum of money can bring back the dead. Minow also points out that “awarding”monies can play into cultural stereotypes, further poisoning the social atmosphere. The issue of public space is extremely charged and Minow could have explored the subject at greater length. She does, however, tell a fascinating story about the Shaw relief in downtown Boston. Although it commemorates a Civil War battle fought in 1863, it was not until 1982 that the names of the fallen African-American soldiers were added to the sculpture–a victory won only after considerable protest. Apologies–like that made by President Clinton for the Tuskegee Experiment, by Tony Blair for the Irish Potato Famine or by the Vatican for its complicity in the Holocaust–often come belatedly, and for reasons of political expedience. Minow astutely points out that such apologies run the risk of being “soliloquys” that assume forgiveness, crowding out the very victims they purport to engage.

This book grew out of Minow’s work with Facing Ourselves and History, the Boston-based group which develops curricula dealing with the Holocaust and other forms of violence. This initiative–which has set standards nationwide–is inspired by the belief that we need not be prisoners of history, that prevention is possible. This message is powerfully introduced in the Foreword by Richard J. Goldstone, former Chief Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunals on the Former Yugoslavia and Rwanda and Judge, Constitutional Court of South Africa.

Fall 1998

Marguerite Feitlowitz is the author of A Lexicon Of Terror: Argentina and the Legacies of Torture (Oxford 1998). A former Bunting Fellow, she has won two Fulbrights to Argentina and currently teaches in the Expository Writing Program at Harvard.

Related Articles

Caballero wins Colombia’s top journalism prize

Building on work she started at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, investigative journalist Maria Cristina Caballero has won Colombia’s top journalism prize…

The Environment in Latin America

This issue of the DRCLAS NEWS deals with some of the environmental problems of Latin America, one of the priorities of the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies…

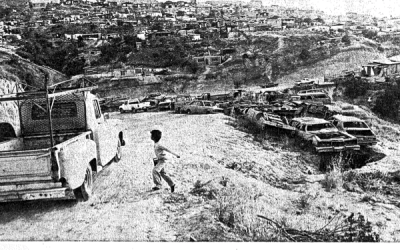

The Urban Environment

Urbanization has transformed Latin America over the last forty years. Its cities, always diverse and lively, have now also become chaotic and centers of social conflict. Millions of subsistence…