Beyond the Political Pendulum

A New Type of Political Consensus?

In 1994, Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa asked David Escobar Galindo what he thought was the most transcendental change in El Salvador between the elections held before the peace accords and the elections to be carried out that year, the first in which the former guerrillas—the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN)—had ever participated. Escobar, member of the El Salvador government commission that had negotiated the peace accords, replied with his typical insightfulness that Salvadorans “now don’t know who will win the elections.” The uncertainty of the electoral outcome, in contrast to the certainty of the previous thirty years in El Salvador because of scandalous frauds, is one of the principal requirements for all electoral contests anywhere.

The Vargas Llosa interview in El Salvador came two years after the 1992 signing of the peace accords. History had shifted with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. In nearby Nicaragua, the ruling revolutionary Sandinistas were swiftly weakening, and in El Salvador, the candidate of the political right—represented by the Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA)—had defeated the Christian Democrats at the polls.

That political context pushed the armed actors to negotiate. Frank dialogue, with the United Nations as witness, led to a political pact with more relevance even than the 1821 declaration of independence. The signing of the peace accords took place at the emblematic Chapultepec Castle in Mexico City on January 16, 1992.

FMLN negotiator Salvador Samayoa, who signed the peace accords on behalf of the former guerillas, said that from that date on there would be an “explosion of consensus” (Samayoa, 2002). As a result of that historical event, a good portion of El Salvador’s democratic institutions began to experience new life. The Armed Forces became subordinate to civil power; the electoral commission underwent a profound transformation; the way in which Supreme Court judges were elected was modified and an Attorney General Office for Human Rights was established. The protagonists of peace accepted electoral democracy as the best mechanism for distributing political power. Between 1994 and 2015, fourteen elections have been held in El Salvador: five presidential and nine congressional and municipal.

Yet it took until 2009 for the FMLN to win the presidential elections, defeating the right-wing party that had governed the country for the previous twenty years.

However, during the two-decade period in which the presidency had remained in the hands of one party, the FMLN exponentially increased its quota of political power, both in the legislative assembly and in local races. Maintaining presidential power within one party caused the democratic transition that began in 1992 to be seen as limited. The alternation of power was needed to consolidate the peace accords and increasingly, with more and more conviction, the political parties recognized the possibility of alternation as a stabilizing factor in Salvadoran politics.

At the same time, the country’s historic polarization kept fear alive about traumatic changes in government that would recklessly swing from one ideological current to another. Fear of what irreconcilable differences could bring was inherited from the pre-democratic society and had endured in the period following the signing of the peace accords, hindering the country’s transition to a new democratic society. However, both in 2009 and 2014, the political parties accepted the popular will without much fuss. Mauricio Funes and Salvador Sánchez Cerén, respectively, won the elections without the principal opposition party or de facto groups’ boycotting the legitimacy of both electoral processes. Thus, despite the narrow margin in the election results in both elections, 2.56% in 2009 and a mere 0.20% in 2014—the narrowest difference between two presidential opponents in the history of elections in Latin America—the losers accepted the decision of the courts processing challenges of the election results.

Now that the country has managed to break the pattern of one-party presidential control, new challenges have emerged. The FMLN administrations have shown both positives and negatives—lights and shadows, as we say in Spanish. Each of the candidates who became president has shaped the presidency through his distinct personality and history. Mauricio Funes Cartagena is not a FMLN militant and wasn’t when he ran for president. He maintained an erratic relation with the FMLN during the five years of his presidential mandate. The fact that he was not organically connected to the party gave him room for maneuver in decision-making. In the context of the political and electoral climate, he could decide how much weight to give to the FMLN party line in shaping his strategies. Despite moments of political wavering, in general, the former president counted with the support of the party for most of his presidency.

The current president, Salvador Sánchez Cerén, is a historic leader and founder of the FMLN. This fact alone is enough to explain his firm commitment to the leftist party. These close ties have been demonstrated by his support of his legislative bills by the FMLN leadership and its group in the legislative assembly, as well as by his own concrete actions to consolidate the party’s political project.

For example, the minister of agriculture and the vice-ministers of economy and education are former executives of Alba Petroleum. This mixed-economy consortium made up of Petróleos de Venezuela (PDV Caribe) and ENEPASA, a communal association of FMLN mayors, has received Venezuelan soft-term loans since 2007. El Salvador is the only place where commercial relations have been established between the Venezuelan state and a business enterprise. In other countries that are members of Petrocaribe—the oil alliance of many Caribbean states with Venezuela to purchase oil with preferential payments—the relationship is between states. Several ministerial-level programs receive economic support from Alba Petroleum.

Alba Petroleum also financed FMLN candidates in the 2014 presidential campaign and in the 2015 legislative and municipal races. A study by the University of Salamanca in Spain showed how the ties of Alba Petroleum with a political party could result in social programs being used for political clientelism, that is, to obtain an electoral advantage for the FMLN (Ferraro and Rastrollo, 2013). A similar case took place in 2004 when Taiwan allegedly financed the campaign of a right-wing candidate. The lack of regulation of campaign financing allows this type of irregularity.

The drop in international oil prices and the current political situation in Venezuela, with the opposition now in the majority in the National Assembly, might obligate the government of President Nicolás Maduro to revise the politics of soft loans, a step that could pose a problem to those countries benefiting from these favorable terms

Nevertheless, diverse evaluations of the six-and-a-half years of FMLN governments point to an improvement in the social sphere. Sustained effort has been made to improve dialogue between political parties through groups such as the Economic and Social Council, the Association for Economic Growth, and more recently, the National Council on Citizen Security and Coexistence, the National Council on Education and the Alliance for Prosperity. Access to public information has also improved and there is a greater degree of independence in government watchdog agencies.

However, the financial sustainability of the government’s social programs, as well as their welfare-like nature, has been questioned. Although the participants in these spaces of dialogue recognize the effort involved in these social programs, they point out that implementation of these programs has not resulted in concrete actions to make the economy more dynamic and to resolve the problem of lack of citizen security. There has also been criticism of the area of government transparency and of the efforts of FMLN legislators to remove Supreme Court magistrates in charge of constitutional questions.

Four of these five magistrates were elected by the National Assembly in 2009 with the support of the two majority parties and the rest of the small parties, and since then, court rulings have begun to grant more independence to state institutions and to bring more transparency to the use of public funds, as well as guaranteeing a series of citizens’ political rights through electoral reform. These decisions put an end to many bad practices that permitted manipulation of oversight institutions such as the Supreme Electoral Tribunal, the Supreme Court and the Attorney General’s Office. Court decisions also did away with loopholes that allowed unmonitored executive use of funds and, in general, the rulings contributed to greater political dynamism and transparency.

The FMLN opposed several of these decisions. Together with three minority parties, it set up a commission to investigate the nomination of the four new judges in order to bring political charges against them. The coalition tried to reform the Law of Constitutional Procedures to block decisions on pending cases. In 2012, a serious institutional crisis developed when the coalition of parties rejected a court decision involving the appointment of Supreme Court magistrates. However, pressure from civil society caused the coalition to adhere to the Constitutional Chamber’s decision.

Thus, the alternation of political parties in the presidency did not eliminate the tensions associated with a distinct form of governing. The arrival to power of a new political party generated anxieties that must be correctly managed. The current administration and the previous one mark the first time in El Salvador that a leftist party with socialist tenets has been elected, and expectations and fears, even now, have reached a very high level. Uncertainty and lack of confidence by business in particular and also by much of civil society have been justified in part because of the FMLN’s past history and the ideological orientation of its proposals. Its vision of the economic and political system and its points of reference in Latin America forecast—and continue to suggest—incorporation into the ideological camp led by Venezuela.

It was also expected that relations with the United States might deteriorate, given the historical discourse of anti-Americanism of the official party, although both the Funes and the Sánchez Cerén administrations have maintained close cooperation with the U.S. government.

Up until now, both the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court through its decisions, and civil society movements through their actions, have managed to ensure rule of law with the republican, democratic and representative state established in the Magna Carta. El Salvador has not joined the Bolivarian Alliance and the constitution has not suffered reforms in its irrevocable clauses. The country conserves a degree of liberty that guarantees fundamental constitutional rights to its citizens—although in a fragile manner and with implicit intimidation. However, the courses of action proposed by the FMLN congress held on November 6-8, 2015, may soon strain the political balance as a result of the ideological antagonism expressed in the conclusions of this meeting.

The documents from this meeting elaborate the principles, form of organization and strategies of the FMLN (Arauz: 2015). The party reaffirms itself as a “hegemony of the left” and points to an “imperialist and oligarchical plan” to “destabilize” the current government. In response, according to the documents, the party seeks to do away with “neoliberalism” through the “de-privatization of strategic goods and services.” It also seeks to set up social and mixed public-private property and to do away with the dollarization of the economy (El Salvador’s national currency is the dollar).

The postulates of the party congress openly contradict the commitments of the FMLN presidential and vice-presidential candidates during the March 2014 election runoff, in which they guaranteed, if elected, to respect the separation of powers, individual liberties, private property, the prudent and transparent management of public finances, and the promotion of dialogue. The contradiction between the candidates’ declarations and those of the FMLN party congress makes it difficult to stimulate a meaningful dialogue, which is necessary if the country is to progress.

The challenges for the FMLN, and certainly for Salvadoran civil society, are great. El Salvador must move from an electoral democracy to one in which independence of the executive, legislative and judicial powers is not merely a transitory characteristic. The institutionality of the government cannot be a battlefield on which “zero sum” political warfare is constantly being waged in obedience to the wartime dictum, “those who are not my friends are my enemies” (PAPEP 2015). The country needs structural and sustainable agreements with a new political consensus that would manage to overcome the current systematic difficulty to reach political agreement. In short, we need to do away with the pendular movement that keeps the country hanging between a recent past and a future that we have not yet finished constructing.

Spring 2016, Volume XV, Number 3

Luis Mario Rodríguez R. is the director of Political Studies of the Salvadoran Foundation for Economic and Social Development (FUSADES). A member of an advisory group for the United Nations Development Programme’s Project for Political Analysis and Prospective Scenarios (PAPEP), he was the executive director of the Salvadoran Private Business Association (ANEP) (1998-2004) and Secretary for Legislative and Legal Affairs of the Presidency (2004-2008). He holds a doctorate in law from the Autonomous University in Barcelona, Spain, and a master’s in political science from the Jesuit University in El Salvador.

Related Articles

The Boy in the Photo

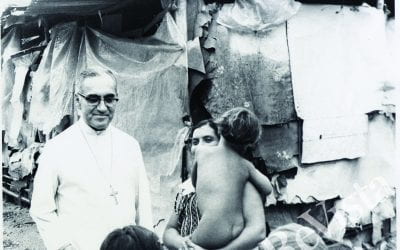

The mangy dogs strolled everywhere along the railroad track. I remembered dogs just like them from the long-ago day in La Chacra in 1979 with Archbishop Óscar Romero, just months before he was killed…

Beyond Polarization in 21st-century El Salvador

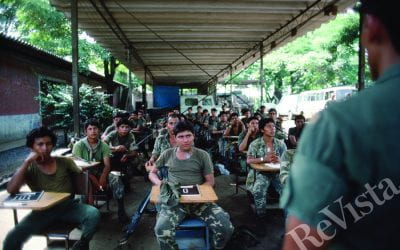

My father was a civil engineer who worked for the government during the civil war years. He specialized in roads and had to spend several days a month traveling to remote places in El Salvador. I was 10 in 1986, and I remember my mom asking my dad…

El Salvador: Editor’s Letter

I had forgotten how beautiful El Salvador is. The fragrance of ripening rose apples mixed with the tropical breeze. A mockingbird sang off in the distance. Flowers were everywhere: roses, orchids, sunflowers, bougainvillea and the creamy white izote flower…