Bilingualism in Multicultural Classrooms in Puebla, México: Sharing School Experiences

Schools in Puebla, Mexico face new and growing challenges. Since 2005, large migratory flows of indigenous people have been arriving in the city, according to the Mexican Institute of Statistics, Geography and Informatics (INEGI). Many of the children go to public schools and formed by the national educational curriculum. The cosmovisions and indigenous languages are pushed aside and as a result, the knowledge passed down from generation to generation is sidelined.

Linguistic conflicts take place on a daily basis in the multicultural elementary school classrooms in the public schools. We have been investigating two generations of students in the Bilingual Elementary School “Emiliano Zapata” located on the outskirts of Puebla and enrolled in the public subsystem of Indigenous Education. I arrived at the school in the decade of 2000, just when the level of education policy and the paradigm of Intercultural and Bilingual Education (EIB) was at its height. Later, from 2010 to today, we have been working with the second generation of students in the same school, that is to say, with the children of some of the students from the school’s first years.

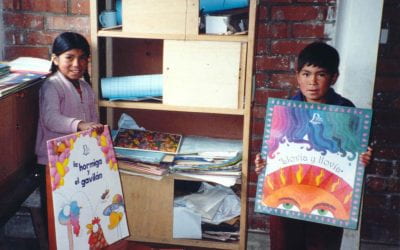

One of the most exciting developments has to do with computers. In this school, the teacher in charge of the computer room is very dedicated to designing teaching material appropriate to the children’s languages and cultures through the use of specialized software that can produce cardboard books and digital texts for some of the teachers to use in their classrooms. National organizations such as the National Institute of Indigenous Languages (INALI) and the General Direction of Indigenous Education (DGEI) have lent their logotypes to provide accreditation and support to these products which were elaborated with the scant economic resources of students and teachers. These organizations honored this work and are considering republishing it to share with other intercultural and bilingual schools. But let’s begin at the beginning, when I arrived at Emiliano Zapata.

Lingistic Diversity in City Schools and Teaching Practices

In these city classrooms, I learned to appreciate the mingling of different ethnic groups, cultures and languages, products of migrations, and how these contacts translated into conflicts among different groups of indigenous people. My initial observations let me appreciate the significant number of children who were linked to the indigenous world, judged by their facial types and by their use of languages other than Spanish.

In 2001, linguistic and socio-cultural diversity in the Emiliano Zapata school had hardly been noticed. Schoolteachers perhaps hadn’t paid attention because of their lack of knowledge about different indigenous languages nor did they have the anthropological curiosity to investigate what groups their students belonged to. They opted for the convenient strategy of assuming that since their students had been born in the city, they were all Spanish speakers. Most of the teachers concentrated on imparting the contents of the program; the rest, as tends to happen in other schools we’ve researched, just put exercises on the blackboard and students copy them down.

Although the school has been designated as a bilingual one, and therefore must teach a second language (náhuatl), teachers never make an effort to provide a bilingual education, mostly because most of them are not biingual themselves. They teach their students a sentence here and a phrase there. Students learn how to greet their teachers in náhuatl, for example. The hour of language study required by the program becomes reduced to the teaching of simple phrases. The bilingual program en Puebla, in the subsystem of indigenous education, focuses only on the teaching of náhuatl as an indigenous language because at the federal level, it is the language with the greatest number of speakers, although in Puebla, most of the students speak mazateco because they come from the Oaxaca countryside.

During my visits in 2002, I found children in third grade who didn’t even know the vowels. I decided to teach them myself, and took five indigenous girls under my wing. Three of the girls came from towns around Oaxaca and their mother tongue was mazateco. The two others were from the northern part of the state of Puebla. They didn’t speak a native language, but they told me that their grandparents did. Three of the girls had not attended preschool before enrolling in elementary school. The girls’ parents—except for two of them—did not know how to read or write so they could not help their daughters with their homework.

These are some of the lived experiences that have not been contemplated by the Secretary of Public Education, the General Direction of Indigenous Education, government officials, leaders and planners. Without understanding these realities, it is nearly impossible to put into effect an effective bilingual education policy. In reviewing indigenous education policies over the years, it is easy to see errors in their design, but even more so, in their execution, going from one failure to another.

Processes of Reading and Writing: Learning Experiences

It’s no coincidence that indigenous children, mostly mazatecos from Oaxaca, take a longer time to learn how to read and write than their mestizo classmates. Teaching reading and writing in a language other than the mother tongue implies a greater time investment, especially since these children come from an oral, rather than written, culture. Moreover, in the school, the culture of these indigenous children—their way of life, language and beliefs—is virtually obliterated. Their culture is not recognized and even less respected. They generally do not perform well in school and their lack of ability to use “correct” Spanish is generally attributed to a lack of aptitude and ability rather than to an understaning of their cultural identity.

Another common problem teachers have in the classroom is that when they are asked if some of their students are speakers of an indigenous language, they immediately answer no since most of the children have been born in the city. This criteria distorts the reality of linguistic diversity.

We did some dictation exercises with first graders, asking them how old they are and where their parents came from, as well as if they spoke some indigenous language. In a group of 55 students, more than 15 spoke mazateca, three náhuatl and one totonaco. These answers helped confirm that indigenous immigration to the zone was very relevant to school education.

In another group of third graders, 16 children asserted that that they did not speak an indigenous language, but when I insisted with my questioning, they said they wouldn’t like to speak another language because “we’ll get teased,” and “they’ll call us “little Oaxacans,” “burros” or “Indians.”

After working with the self-esteem of these children, showing them the importance of speaking their mother tongues, finally one of them admitted to speaking an indigenous language. Others followed. A discussion of how to write a series of words in mazateco ensued, which the school had never taught them. The child who had shown so much resistance to revealing that he spoke mazateco was the leader in figuring out how to write it.

When I visited the home community of these mazateco children in the state of Oaxaca, I met a literacy worker from the Mexican Institute for Adult Education and asked her to look over the childrens’ work. She said there were some spelling mistakes in their writing, but the meaning was completely understandable.

I continued to work in the school, and I could see that as the years went on, from 2010 to the present, the school administration and teachers became open to the value of sociocultural and linguistic diversity. Teachers collaborated with some of the parents to develop strategies for writing náhuatl and mazateca. Although the latter language was the most prevalent among the students, the truth was that not a single teacher spoke it.

Children in a náhuatl class drawing parts of the body

Texts in náhuatl with accompanying translations by the students

Bilingual education plans for 2018 led to a pilot program, in which teachers would work in Spanish and a native language, and that teachers should commit themselves to the rehabilitation and strengthening of indigenous languages, developing strategies for reading and writing in their lesson plans. Nevertheless, of the three teachers with whom I worked in 2018, two of them, the first-grade teacher “C” and the third-grade teacher “A” speak náhuatl, while the third-grade teacher “C” does not speak an indigenous language. But even those who do find it difficult to sustain the teaching of the language through their curriculum, based on a bilingual balance and attention to all of their students because of the linguistic complexity of their classrooms.

The books provided by the bilingual education system have the same deficiencies as they did decades ago. They only offer náhuatl and they do not take into account the ethno-cultural aspects of the different regions from which the families of the children hail. The software program helps overcome some of these challenges.

My bilingual book (first grade)

This computer software provides a fundamental support for the teachers—different from that found in other Puebla elementary schools, not just in the teaching and learning of indigenous languages, but in all subjects. Lucy Zamudio, the teacher in charge of the computer salon, has used her creativity and availability so that teachers can reinforce concepts taught in their classrooms. She has developed computer programs in the languages of the students.

Zamudio gives out computers t the students, but there aren’t enough to go around. Sometimes up to four students share a computer and take turns using it. From fourth grade on, the groups are divided so that students can work on computers individually.

For example, curriculum requirements make English a requirement as a foreign language (which no other public school has managed to implement), Zamudio has created a book with names of basic objects found at home, not just in English, but in Nahuatl and Mazateco. This means many hours of work beyind the ordinary school day—including recesses—in order to design the book in the computer room.

Material is designed to reinforce knowledge of the indigenous languages with members of the family in Nahuatl, as well as colorful figures of princesses and super-heros. Puzzles and other games are also used to make the process of learning playful.

Students thus learn in a playful way that their languages are not completely static and that, because of the process of migration and geographical contact, words that are used every day may have a different linguistic origin.

Although there is still a long way to go, the recognition of linguistic diversity is a major step forward. We need to do more collaborative research from the vantage point of ethnography to offer a pertinent education for the indigenous boys and girls who immigrate from the countryside to the city. Many social actors can learn together, writing in dialogue with the school texts, so that students can put into action their worlds and particular cosmovisions in relation to what they are learning at school.

Fall/Winter 2019-2020, Volume XIX, Number 2

Elizabeth Martínez Buenabad es profesora en la Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla.

Related Articles

Ghosts of Sheridan Circle

Targeted killing of political enemies—assassinations—is thankfully rare in the United States. The most famous such assassination occurred in Washington, DC. And it was committed by a close ally of the United States. In September 1976, Chile’s Pinochet dictatorship…

Bilingualism: Editor’s Letter

It was snowing heavily in New York. It didn’t matter much to me. I was in sunny Santo Domingo with my New York Dominican neighbors on the Christmas break from school. I learned Spanish from them and also at the local bodega, where the shop owner insisted I ask…

Two Wixaritari Communities

English + Español

I first arrived in the wixárika (huichol) zone north of Jalisco, Mexico, in 1998. The communities didn’t have electricity then, and it was really hard to get there because the roads were simply…