Bogotá: A City (Almost) Transformed

The sleek red bus zooms out of the station in northern Bogota, a futuristic symbol of an (almost) transformed city. Nearby, thousands of cyclists of all ages enjoy a sunny morning on Latin America’s largest bike-path network.

The transmilenio, as the modern bus network is called, moves 750,000 passengers per weekday-almost 100,000 more than Washington D.C.’s subway system. And Bogota’s citizens are proud of their transportation, proud of their city.

That wasn’t always the case. In 1988, during Colombia’s first mayoral elections, a local radio station launched its own “virtual” candidate. The candidate’s transport platform was simple: instead of fixing all the roads, why not remove the pavement remaining to level our potholes. Vehicles would then no longer have to “sink” into potholes-instead they would simply ride over the unpaved street.

Highlighting the deteriorated transportation infrastructure, the imaginary candidate argued rhar his solution would march the city’s scant financial resources. The situation only grew worse. By 1993, Bogota had become totally chaotic. The quality of life deteriorated, with few city services. One could say that the city mistreated its inhabitants, and the citizens reacted in kind. People often tossed their garbage on the street. Drivers careened their cars at pedestrians, actually speeding up as people attempted to cross the street. No one stopped for red lights.

It was not chevere to be Bogotano. Bogota was-and is-a city of immigrants from all over Colombia. These folk always spoke kindly about their places of origin and, when visiting them, behaved well. They would never dream of throwing garbage on a sidewalk in their home town. Yet in Bogota, fewer than ten years ago, the fashion was to mistreat the city. The city did not meet the expectations of the citizens and as a result, the citizens did not feel a bond with it.

Today, Bogota is a transformed city almost. Transportation infrastructure and policies are now so innovative that many cities in Larin America plan to follow its example. Overall service delivery by the city government is probably the best in the country. And more importantly, inhabitants love their city; it is now chevere to be Bogotano.

What happened in this short period of time? How could a city emerge from its worst crisis to become such an innovator in urban policy that its government has won several international awards and prizes? I’ve tried to answer these questions in this essay through the lens of Bogota’s urban transport sector, which has probably witnessed the most substantial transformation relative to other city services.

THE MONEY MAKER AND “FOUNDING FATHER”

The “founding father” of rhe (almost) transformed Bogota is Jaime Castro, Bogora’s mayor between 1992 and 1994. And I say, ironically of course, rhar he is rhe “founding father” because he wrote Bogora’s 1993 Charter. When I interviewed Jaime Castro for my research in November, 2001, I asked him about the process for drafting and enacting Bogota’s Charter, specifically about who had participated in the process. His response, after a short pause, was “well. .. me … only me … with the help of one expert in municipal finance for that part of the Charter.”

Sounds aurhorirarian? Sure. Bur Bogota was lucky enough to elect a knowledgeable, responsible mayor who could go beyond the usual authoritarianism that creates a caudillo—a leader followed blindly by the people.

Bogora’s Charter is important to the story I am telling. First, the municipal finance section of rhe Charter modernized the tax code of Bogota and gave the city instruments to significantly increase its revenues. In 1994, tax collection was almost twice that in 1993. Tax revenue continued to grow rapidly until the 1999 Colombian recession. With more funds, the city was able to invest more in many areas including transportation, significantly improving road conditions.

Second, the Charter created a very strong executive, weakened the city council, and most importantly, opened the doors for civil society to participate in rhe decision-making process. Certainly I do not condone weakening the powers of rhe city council-or for that maner creating an authoritarian mayorbur introducing civil society as a legitimate political actor was very important because ir democratized city government and helps explain rhe transformation of Bogota.

BUILDING CITIZENSHIP

In the 1994 elections, Bogotanos elected Antanas Mockus as mayor. The liberal parry candidate, Enrique Penalosa, lost because party politicians had fallen out of favor. Mockus is to some extent the quintessential anti-politician-he was an academic, lacked a political parry when first elected, his campaign cost only $3000 dollars, and he had never been elected before.

Yet he had ample experience-he had been president of the National University of Colombia and had lobbied Congress using a plastic-toy sword to defend the budget allocation for the University, which Congress was planning to reduce. Mockus, above all, believes in the power of symbols to communicate and transform-hence the plastic sword as a symbol of his will to fight for the University.

Mockus argued that Bogotanos needed to learn how to be good citizens, that lack of citizenship was why they mistreated the city, evaded taxes, and why violent crime was so high, among others. His first priority was therefore to “build citizenship” through several campaigns that used symbols, many of them relating to transportation. Campaigns tried to teach people to obey basic traffic laws such as stopping at a red light, giving priority to pedestrians and taking the bus only at bus stops.

An example of one of these campaigns was handing out plastic cards with a “thumbs-up” on the white side and a “thumbs-down” on the red side. The cardholder would show the “thumbs-up” to a fellow citizen who was behaving well-ceding the way to a pedestrian in a crosswalk. If the behavior was not that of a “good citizen” then you could show the thumb-down side, which reminded everyone of the famous red cards used in soccer to expel a player from the field-notice the symbol embedded in the use of the cards.

The educational campaigns, however, were poorly implemented. For example, judging what is the proper behavior of a “good citizen” can be arbitrary and the city administration did not offer much guidance. Thus, the educational purpose of the cards did not always materialize and, worse, the use of the cards became illegitimate for parts of the citizenry. The use of cards was discontinued halfway through the administration and other policies were implemented instead.

Despite these problems, Bogotanos did change their behavior noticeably. It became more common to see drivers stopping for pedestrians, and both bus drivers and riders using bus stops. Equally important, people started changing the way they viewed the city, identifying with the city in a positive fashion.

Mockus also started the planning of important initiatives in the areas of public space and transportation. He planned and slowly implemented policies to recover public space from street vendors and illegally parked cars. He also had planners design enhanced sidewalks and his administration built the first paths for the exclusive use of bicycles. In transportation, the Mockus administration carried out extensive studies for improving and expanding the “bus rapid transit” network of the city-more on this below-and discarded plans for the construction of a subway line because of excessive costs.

Despite the effort put into these initiatives, it would be Mockus’ successor (Colombia prohibits immediate reelection), Enrique Penalosa, who would significantly improve and enhance these plans, implement them and carry out the physical part of the transformation of Bogota. Yet Mockus had achieved a great deal. A transformation had started, the government was delivering on its promises, and people had begun to build a sense of belonging, treating the city better as a result.

(RE)-BUILDING THE CITY

Enrique Penalosa, now as an independent candidate, was elected mayor late in 1997 on a platform that emphasized building infrastructure as a catalyst for social and economic change. Penalosa inherited the city in good financial shape, and he was lucky enough to also benefit from significant proceeds from the City Power Company’s privatization.

This windfall allowed Penalosa to launch the most important construction program in the history of the city to transform-almost the face of Bogota. This program was so enormous that graffiti sprung up declaring “promises, yes, construction, no”-an ironic critique of past mayors who promised a lot but built little and a protest of the fact that most of the city had become a construction site.

The development of city infrastructure catalyzed a social transformation because people were beginning to see a city that delivered, a city with a different, kinder, friendlier face. A city that looked well taken care of and that people would therefore find difficult to litter, to mistreat, a city where “behaving well” matched the new “look” of the city.

And this certainly worked-as it has in many other cities. The main example of Bogota’s social transformation through infrastructure is TransMilenio, a bus rapid transit project where the infrastructure and buses are modern, beautiful, and clean, and the system is respectful of the user. People respect the system, feel protected by it, and as a result they protect it from anyone crying to harm it.

The still-functioning old bus system, with its mostly decrepit and polluting vehicles, gets little respect from its users and is vandalized frequency. Even its operators barely stop to collect and drop off passengers, endangering the lives of the users and disrespecting them. Clearly, TransMilenio is the new public image of the city-people agree to meet at its stations, which have become landmarks-and people are collectively proud of its facilities and the important step forward it represents.

Building infrastructure was also expected co catalyze economic development. The line of reasoning is that if the infrastructure is sound, the city will look better and hence capital, particularly foreign, will find a good and safe city co invest in. Certainly, some economic growth has been seen as a result of this huge investment in constructing city infrastructure-from sidewalks to busways, to schools and day-care centers, to wide avenues and the largest bike-path network in Latin America. Yee this assumption was not enough because of slow economic growth and the impact of the war in the countryside. As a result, poverty kept growing in Bogota.

Overall, the most important result of the construction program was a facelift for the city. Again I use the TransMilenio bus rapid transit project as the showcase example. Bus rapid transit seeks to transfer the advantages of a metro co bus service-boarding from a station, paying when entering the station, vehicles stopping only at stations. The main objectives are to use buses co move thousands of passengers at a relatively high speed, without congestion and with comfort. To achieve this, bus rapid transit builds segregated lanes for the exclusive use of buses; cars and trucks use separate lanes. Stations are also built so that users pay when entering the station and they can board the bus as soon as station and bus doors open.

The results of TransMilenio’s first stage, a total of three lines, are impressive without a doubt. The system moves 750,000 passengers per weekday-almost 100,000 more than Washington D.C.’s subway system. Yee the latter has a network of over 100 miles and TransMilenio’s first stage is only 26 miles long.

Buses now flow much faster than before and save time for riders. Thousands of people who usually commuted by car switched to using TransMilenio. And because the buses are environmentally friendly there is a net environmental gain. Further, the cost of TransMilenio was only a tenth of a never built subway line with a similar alignment.

To implement these changes and projects in the short three-year mayoral term Penalosa resorted to a team of highly qualified planners. Penalosa argued in an interview that given the critical situation of Bogota there was no time for debates, discussions, and consensus building proper of democratic practice, and acknowledged he had to “make a number of strategic decisions in a rather undemocratic manner.”

The preliminary results of my dissertation-TransMilenio is one of the cases-are that at least for the planning and implementation ofTransMilenio’s first stage, the latter was not true. Instead, the planning team conducted many debates and discussions with relevant stakeholders and even the population at large. Planners took advantage of the enhanced participation of civil society allowed by the city Charter and were therefore able to assemble a coalition in support of the project that ultimately made the project politically feasible.

Interestingly, Penalosa faced strong opposition precisely when he and his administration team forgot to address controversies in a “democratic” manner. For example, Penalosa launched policies to restrict car use, including not allowing cars to park on sidewalks. These policies, contrary to the process followed for TransMilenio, were launched without much explanation of their rationale and benefits and without paying attention to people’s concerns and recommendations for improving policy design. Instead, their implementation was founded on “authority” and speedy decision-making to save time, as Penalosa himself recognized.

The result was disastrous. Penalosa’s approval rate fell to record lows and an effort impeach him almost succeeded. Sheer to luck saved him from this fate and he was able to finish his term successfully, after changing his style towards one more aware that elected politicians need to explain their proposals-even if the campaign is over and gather political support for them. Further, policies need to be adapted to political reality if they are to become feasible.

BOGOTA: ALMOST TRANSFORMED

In 2000, Antanas Mockus was reelected as mayor and continued with reform, but at a slower pace due to a lower availability of funds. In the short time span analyzed here, Bogota went through a significant process of successful transformation. Change was possible because of a combination of policies ranging from improving tax collection using symbols and infrastructure to achieve social change. Leadership played a role, but equally as important was opening political space to include civil society in planning and decision-making and in making politicians accountable.

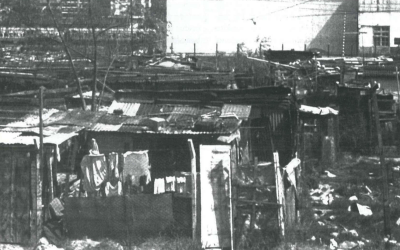

Despite these important advances the transformation is at best incomplete. Not only are there thousands of sidewalks left to be enhanced and beautified, there are many other lines of TransMilenio left to be built. More importantly, despite all the public investment, poverty and unemployment keep growing at a fast pace.

Paradoxically enough, what used to be a middle class city could rapidly become a pauperized one. The solution probably lies in slowing the pace of building infrastructure and in designing policies that promote local economic growth, firm development, and job creation-policies that have never been part of Bogota is mayoral agenda. Yet citizen are clamoring for change in this direction in their almost transformed city.

Winter 2003, Volume II, Number 2

Arturo Ardila-Gomez is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He is a Fulbright Scholar.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Cityscapes

I have to confess. I fell passionately, madly, in love at first sight. I was standing on the edge of Bogotá’s National Park, breathing in the rain-washed air laden with the heavy fragrance of eucalyptus trees. I looked up towards the mountains over the red-tiled roofs. And then it happened.

Social Spaces in San Juan

My city, San Juan, is a social city. Its character and virtue are best illustrated and defined by the collective and individual memories of its people and those places where we go to spend time in idleness….

Low-Income Housing in El Salvador

El Salvador’s tremendous housing deficit had slowly begun to improve in the late 1990s. Then devastating twin earthquakes in early 2001 literally shook the country’s economic and social …