Colonial Shadows

Obstacles For Imagining Community

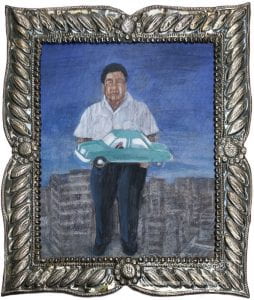

- El Chofer (The Chauffer) from the series, “La tuya, la mia, la nuestra” by Moico Yaker, 1998. Courtesy of Gustavo Buntinx.

- “Pamplona casuarinas” by Roberto Huarcaya, 2011 (Micromuseo collection). Image courtesy of Gustavo Buntinx.

- “Playa publica/playa privada (Public Beach/Private Beach), 2009, by Roberto Huarcaya. Image courtesy of Gustavo Buntinx.

- Untitled work by Eliana Otta from the series “Senores de la intemperie” (Lords of the Elements) 2013. Image courtesy of Gustavo Buntinx.

- Untitled work by Eliana Otta from the series “Senores de la intemperie” (Lords of the Elements) 2013. Image courtesy of Gustavo Buntinx.

Peru is immersed in a new wave of capitalist modernization; its market has expanded in an extraordinary fashion and social mobility is now possible. However, we are still far from conceptualizing ourselves as a nation or an imagined community, to use Benedict Anderson’s famous phrase: we still do not perceive ourselves as a collective of citizens all equal under the law with the same rights and responsibilities.

Something remains of an old history that does not manage to lose its grip, that is repeated over and over again in a karmic fashion and continues to play an important role in our society. Although a new era is emerging in which Peru is governed by the middle classes, the old vices of extreme inequality arise all too often in the interaction among Peruvians, including tutelary practices, traditional or reverse racism and the mania to create hierarchies.

As a part of a larger research project, we seek to look at the way in which contemporary art recognizes these failures, concentrating on just four of the many artists who try to show things that our daily inertia makes invisible. Our unimagined communities.

The works of art we look at show an awareness of the huge gaps that impede the construction of more just relations among Peruvians. Through the use of different aesthetic resources, these works reveal what is evident but often denied in the emotional and political registers of everyday life: those hidden colonial shadows that threaten the most recent liberation of our vehement and legitimate (post)modernity. Ominous remains of a traditional past—remnants of an old order that still keeps alive within us.

Sometimes these works are marked by profound ambivalence, a reflection also of a certain social indefinition experienced by many artists. The subject of domestic employment is in this sense incisive, because of the intimacy—even the affective intimacy—with which servants embody differences in social class. The emotive portraits of his parents’ servants that Moico Yaker created in 1998 show an anguished personal testimony and a loving symbolic reparation: although small, all of the paintings are framed in embossed silver, the repujado technique whose colonial overtones today conjure up images of sentimental or religious devotion. These connotations are also present in the distinctiveness of the servants, and each of their tasks is portrayed as a particular attribute, similar to the way the Christian saints were identified in viceroyal paintings by the instruments of their martyrdom. The waiter stands with the napkin on his arm; the chauffeur sadly shows off an automobile that is not his own. And the laundrywoman is immersed in a huge vat whose dirty waters seem to have washed her features half off.

In contrast to these unique images, diminutive but individualized with first and last names, between 2006 and 2008 Adriana Tomatis reinterpreted in huge paintings the uniformed anonymity of the nannies, sometimes accompanied by the children under their care. A complex rendering of plastic and conceptual modes, underscored by disturbing titles such as Prueba de color (Proof of Color) or Blanco sobre blanco (White on White). Or indeed La otra (The Other), an explicit reference to photographer Natalia Iguíñiz’s series on the same theme.

Tomatis is also the creator of Panic Room (2009-2013), a caustic sequence of drawings and watercolors that depict, in an architectural fashion, the omnipresent and somewhat shoddy booths set up for hired security all over Lima; our great capital city that is pathetically unprotected by the incompetent and corrupt police force, and by the state apparatus in general. It is this precariousness that her drawings ironize, with a sharpness in counterpoint to the beauty of plastic expression.

For some months now, Eliana Otta has opted for the opposite formal strategy. She treats the same issues through a series of eight photos that are deliberately insipid: barely registered dull images of the worn-out seats that hired guards are provided with in the frightened middle-class neighborhoods. They are a vestige of common household items, a domesticity that now pervades public space and politically impacts us through the scenes depicted in these photos. These chairs—old, broken, uncomfortable—slowly reveal themselves to us as a moving attempt to fill the gap left by the state, but they also provide additional evidence of the precariousness of work, of still lamentable conditions in some contexts of our recent prosperity. The title could (almost) say it all: Señores de la intemperie—Lords of the Elements.

But all this is achieved not by representing individuals, but rather the tools of the work that defines them. These off-center images reject the current popular aesthetic, reminiscent of advertising, that “includes” working-class figures in almost postcard style. On the contrary, in Otta’s (and Tomatis’) images, the subject—the figure of the security guard—does not appear anywhere, and we must face the disturbing nature of pure objects. These chairs—the kind that we would never find inside one of the houses they guard—speak for themselves. And they speak of a hidden or minimized hegemony: the instability the political order generates and which, at the same time, paradoxically sustains it. And more: the uncomfortable manner in which some of these guards are still situated, like vassals on the borders of the modernizing process itself.

Two impressive photos by Roberto Huarcaya focus on these and other borders in the most explicit way possible, but not less poetic because of that. A panoramic format and extremely oblong image contribute to the poetic sense, but also to the deficient horizontality in Peruvian society. The decisive element in both photographs is the central and dividing axis marking the center of the composition. The first image (2009) depicts a dock that separates, like a virtual wall, the exclusive beach of the Regatas Club from the popular shores of Agua Dulce and Pescadores. In the second photograph (2011), we have a literal wall—indeed with barbed wire—that prevents people from the working-class neighborhood of Pamplona Alta from transiting near the gated Las Casuarinas condominiums.

The borders are as symbolic as actual. In spite of the undeniable economic mobility and increasing social movement, art works such as those discussed here insist that elements of inequity still persist, the remnants of the great divisions and fractures that have constituted our society. The colonial mentality survives.

P.S.: Pay special attention to the subtle punctum in Huarcaya’s virtual diptych. The secret punctum: the profile of a building appearing above the hills at the extreme right of the first photograph—Playa pública/playa privada (Public Beach, Private Beach)—is where the photographer lives with his wife and children. Practically a beacon for the daily contemplation of the symmetric assymetries that the camera now registers in a reverse form. The artist’s vital gaze of unfolded creation, deconstructed through its own technological—and social—glance.

Sombras Coloniales

Trabas para Imaginar la Comunidad

Por Gustavo Buntinx y Victor Vich

El Perú se encuentra inmerso en una nueva oleada de modernización capitalista: el mercado se expande de maneras impresionantes y la movilidad social ha dejado de estar encasillada en una estructura que limita los ascensos. Sin embargo, todavía nos encontramos muy lejos de articularnos como nación o comunidad imaginada, por utilizar la célebre fórmula de Benedict Anderson: la imagen todavía negada entre nosotros de un colectivo de ciudadanos iguales, con los mismos derechos y responsabilidades.

Hay, así, algo de una vieja historia que no consigue destrabarse, que se repite como un karma y continúa jugando un papel importante en nuestra sociedad. Aunque tiende a generalizarse un nuevo horizonte mesocrático, con excesiva frecuencia persisten en las interacciones entre los peruanos los antiguos vicios de la desigualdad extrema, las prácticas tutelares, el racismo (tradicional o invertido), la manía jerarquizadora.

Como parte de una investigación mayor, esta muestra procura indagar en algunas de las maneras en que el arte contemporáneo acusa esos golpes. Se concentra para ello en el trabajo de apenas cuatro de los muchos artífices que intentan hacer ver lo que la inercia cotidiana nos invisibiliza. Nuestras comunidades inimaginadas.

Las obras reunidas dan cuenta de las brechas que impiden la construcción de relaciones más justas entre nosotros. Mediante la utilización de diferentes recursos estéticos, las composiciones que aquí se articulan ponen en evidencia lo ya evidente pero por lo general negado en los registros sensibles y políticos de la interacción cotidiana. Esas ocultas sombras coloniales que amenazan las liberaciones últimas de nuestra (post)modernidad vehemente y legítima. Restos ominosos de una tradición pretérita pero viva, mediante la que algo del antiguo orden se prolonga y procura reproducirse en nosotros.

A veces con marcas de profunda ambivalencia, que son también las de la incierta definición social de la que muchos artífices provienen. La figura del trabajo doméstico es en ese sentido incisiva, por la intimidad incluso afectiva con que ella encarna la diferencia social. Como en los emotivos retratos de los servidores de sus padres con que Moico Yaker ensaya en 1998 un angustiado testimonio personal y una amorosa reparación simbólica: aunque pequeños, todos los cuadros exhiben esos marcos de plata repujada cuyas reminiscencias coloniales sirven hoy para exaltar imágenes de devoción religiosa o sentimental. Connotaciones también presentes en los distintivos de servidumbre y oficio que cada retratado porta como su particular atributo, a la manera de santos cristianos identificados por los instrumentos de su martirio en la pintura virreinal. El mozo con la servilleta al brazo, o el chofer ostentando con resignación el auto ajeno entre sus manos. Y la lavandera inmersa en la sobredimensionada batea cuyas aguas turbias parecen haberse llevado hasta sus deslavados rasgos.

En contraste con esas semblanzas únicas, diminutas pero individualizables hasta con nombre y apellido, entre 2006 y 2008 Adriana Tomatis reinterpreta en grandes cuadros el anonimato uniformado de las nanas, en compañía a veces de los niños confiados a su custodia. Identidades desdibujadas incluso pictóricamente por un tratamiento formal que desvanece a la vez que estetiza esas presencias silenciadas de la intimidad doméstica. Una articulación compleja de sentidos plásticos y conceptuales, subrayada por títulos inquietantes como Prueba de color o Blanco sobre blanco. O incluso La otra, en alusión explícita a una secuencia fotográfica de Natalia Iguíñiz muy asociable a los temas de esta exposición.

Tomatis es también la autora de Panic Room (2009-2013), una punzante secuencia de dibujos y acuarelas que transfiguran a un lenguaje arquitectónico la presencia ubicua de casetas más o menos improvisadas para los servicios informales de seguridad callejera que se multiplican en Lima: nuestra gran ciudad capital, patéticamente desprotegida por la incompetencia y corrupción de la policía, y en general de casi todo aparato estatal. Es esa precariedad la que estos esquemas ironizan, con una agudeza acentuada por la belleza buscada en la expresión plástica.

Desde hace algunos meses Eliana Otta opta por una estrategia formal opuesta al abordar la misma problemática mediante ocho fotografías deliberadamente anodinas: apenas registros desangelados de los maltrechos asientos que se les suelen proporcionar a los vigilantes privados de las calles en los atemorizados barrios de nuestras clases medias. Un resto de lo doméstico que aflora en el espacio público para golpearnos políticamente desde el encuadre concentrado de estas tomas. Esas sillas –viejas, rotas, incómodas– se nos revelan así como un intento conmovedor de llenar el vacío del Estado, pero también como una evidencia adicional de la precarización del trabajo, de sus condiciones todavía lamentables en algunos contextos de nuestra prosperidad reciente. El título podría decirlo (casi) todo: Señores de la intemperie.

Pero todo logrado desde la re-presentación no de los individuos sino de los instrumentos laborales que los redefinen. Imágenes que desde ese descentramiento rechazan la estética casi publicitaria, hoy tan en boga, de “incluir” al personaje popular, convertido así en tarjeta postal. Por el contrario, el sujeto no aparece aquí por ningún lado, pues se trata más bien de enfrentarnos al carácter perturbador del propio objeto. Estas sillas –que nunca encontraríamos al interior de las casas que ellas resguardan– comienzan a hablar por sí mismas. Y su decir apunta a algo que la hegemonía oculta o minimiza. La inestabilidad que ese orden genera y que, paradójicamente, al mismo tiempo lo sostiene. Y la manera incómoda en la que algunos siguen siendo colocados como vasallos en las fronteras del propio proceso modernizador.

Sobre esas –y otras– fronteras nos hablan también dos impresionantes fotografías de Roberto Huarcaya. De la manera más explícita posible, pero no menos poética por ello. A esto contribuye su formato panorámico y en extremo apaisado, que sin embargo apunta a la horizontalidad deficiente en la sociedad peruana: el elemento decisivo en ambas tomas es un eje central y divisorio marcando siempre el centro de la composición. En la primera imagen (2009) se trata del muelle que separa, como una muralla virtual, la playa exclusiva del club Regatas de las orillas populares de Agua Dulce y Pescadores. En la segunda toma (2011) tenemos la muralla literal –incluso con alambre de púas– que impide el tránsito de las barriadas populares de Pamplona Alta a los condominios cerrados de Las Casuarinas.

En ambos casos la desigualdad es planteada mediante equitativos términos visuales. Izquierda y derecha mantienen su proporción y simetría para la revelación de miserias y opulencias ordenadamente distribuidas. Y segregadas: áreas fronterizas impedidas de convertirse en zonas de contacto.

Fronteras tanto simbólicas como fácticas. A pesar de la innegable movilidad económica y la porosidad social crecientes, obras como las reunidas en esta exposición insisten en los elementos de inequidad que aún persisten. Los restos de la gran división y fractura que constituyeron nuestra sociedad hace ya centurias. La colonialidad supérstite.

P.D.: Atención al punctum sutil en el virtual díptico de Huarcaya. El punctum secreto: entrecortado sobre los cerros a la extrema derecha de la primera fotografía –Playa pública – Playa privada– asoma el perfil del edificio en el que el autor vive con su esposa y con sus hijos. Casi una atalaya para la contemplación cotidiana de las simétricas asimetrías que su cámara ahora registra de manera inversa. La mirada vital del artífice desdoblada, desconstruida, en su propia mirada tecnológica.

Y social.

Fall 2014, Volume XIV, Number 1

Gustavo Buntinx is an art historian, critic and independent curator, and director of the Cultural Center of the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos (Peru). A graduate of Harvard University, where he studied History and Literature, he completed postgraduate studies at the Universidad de Buenos Aires.

Víctor Vich, a Peruvian writer, is a professor at the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú (PUCP) and researcher at the Instituto de Estudios Peruanos (IEP). He was the 2007-08 Santo Domingo Visiting Scholar at DRCLAS.

Gustavo Buntinx, es historiador de arte, crítico y curador independiente, y director del Centro Cultural de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos (Perú). Egresado de la Universidad de Harvard, donde estudió Historia y Literatura, realizó estudios de posgrado en la Universidad de Buenos Aires.

Víctor Vich, escritor peruano, es profesor de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú (PUCP) e investigador del Instituto de Estudios Peruanos (IEP). Fue académico visitante de Santo Domingo 2007-08 en DRCLAS.

Related Articles

The Violence of the VIP Boxes

English + Español

In Peru, the upper class does not like to mix with those they consider different or inferior. Their maids on the beaches south of Lima are not allowed to swim in club pools and, sometimes, not even in the ocean. The VIP boxes at sports and theater events maintained by the government are a public display of a private practice that reproduces in the public sphere the worst aspect of private hierarchical structuring.

Peace and Reconciliation

English + Español

Eleven years have gone by since the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission presented its final report. The report reconstructed the history of many cases of massacres, tortures, murders and other serious crimes. At the same time, it contributed an interpretation of the…

I Ask for Justice: Maya Women, Dictators, and Crime in Guatemala, 1898–1944

On May 10, 2013, General Efraín Ríos Montt sat before a packed courtroom in Guatemala City listening to a three-judge panel convict him of genocide and crimes against humanity. The conviction, which mandated an 80-year prison sentence for the octogenarian, followed five weeks of hearings that included testimony by more than 90 survivors from the Ixil region of the department of El Quiché, experts from a range of academic fields, and military officials.